Mark Wallace on Dubravka Djurić

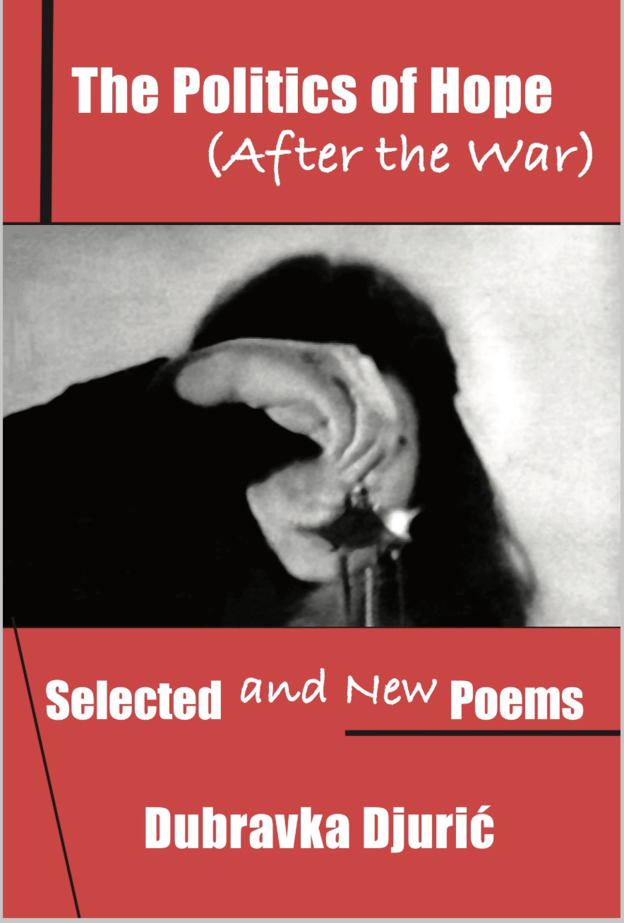

The Politics of Hope (After the War): Selected and New Poems

Dubravka Djurić

Edited and Translated with an interview by Biljana D. Obradović

Foreword by Charles Bernstein

Roof Books, 2023 / 248 pages

Dubravka Djurić has played an important role for many decades in not just the poetry of her original cultural context and language (which she calls “Serbo-Croatian,” a term no longer in official use) but also through her interactions with poets working in English and other languages. The Politics of Hope (After the War) is the first major selection of writing available in English from this significant contemporary European poet, and it offers a broad and informative look at the range of her work. The value of Djurić’s poetry is equally aesthetic, cultural, and political. She explores new possibilities for what poems can be and how they can speak across multiple environments. Her writing also engages the immediacies of political crisis — especially those she experienced during the Yugoslavian civil war —and her feminism, her anti-war stance, and her refusal to side with any single national perspective mark her work as admirable and daring.

The Politics of Hope (After the War) does an excellent job of showcasing the most important changes in Djurić’s work over time. It begins with a few pages of somewhat more conventional lyric and minimalist work from Clouds and Shores / Clouds and Shapes, poems written in 1982 and 1983. However, in the late '80s, with Nature of the Woman / Nature of the Moon: Nine Metaphors (1989), comes the first decisive development, a shift to questioning the nature of poetry and of language itself. These poems, mostly open field in structure, create a variety of metapoetic and metalanguage moments that ask readers not just to view language as a vehicle for image and meaning creation, but also to examine how the vehicle operates, what it can do and, just as powerfully, what it can’t. “Words don’t carry experience / the adventure / They enable the experience / the adventure,” she writes in the poem “Part One of ‘Searching’” (29), suggesting that language is not a passive conductor of physical events, but rather one that shapes those events through an author’s choice of words.

The Politics of Hope (After the War) does an excellent job of showcasing the most important changes in Djurić’s work over time. It begins with a few pages of somewhat more conventional lyric and minimalist work from Clouds and Shores / Clouds and Shapes, poems written in 1982 and 1983. However, in the late '80s, with Nature of the Woman / Nature of the Moon: Nine Metaphors (1989), comes the first decisive development, a shift to questioning the nature of poetry and of language itself. These poems, mostly open field in structure, create a variety of metapoetic and metalanguage moments that ask readers not just to view language as a vehicle for image and meaning creation, but also to examine how the vehicle operates, what it can do and, just as powerfully, what it can’t. “Words don’t carry experience / the adventure / They enable the experience / the adventure,” she writes in the poem “Part One of ‘Searching’” (29), suggesting that language is not a passive conductor of physical events, but rather one that shapes those events through an author’s choice of words.

If the lines quoted above are talking about what language does, later in the same poem the sense of language as limitation, as something that cannot always do what people hope it will, comes more to the forefront:

My language experiences

THE MURMUR

OF THE SEA

differently from other languages

The connection between

The consonants and the vowels

is unusual

in

any word

The memory of the beginning

is strange

Breaking the meaning of

WORDS (35)

When examined closely, Djurić suggests that both the structure of words, and the differences between languages, highlight the problem that experiences are not easily translated from one language or context to another. Along with differences in language, another key difference in experience — one sometimes impossible to bridge — comes from gender. Some of the poems in this section highlight the feminist aspects of Djurić’s work, as in the playful but pointed commentary in “She Is The Other,” Part One and Part Two. Her feminist concerns grow in the following work, Stretching the Frames / Slash of / Context, written between 1988 and 1990 but first published only in 2020.

When examined closely, Djurić suggests that both the structure of words, and the differences between languages, highlight the problem that experiences are not easily translated from one language or context to another. Along with differences in language, another key difference in experience — one sometimes impossible to bridge — comes from gender. Some of the poems in this section highlight the feminist aspects of Djurić’s work, as in the playful but pointed commentary in “She Is The Other,” Part One and Part Two. Her feminist concerns grow in the following work, Stretching the Frames / Slash of / Context, written between 1988 and 1990 but first published only in 2020.

One would have to be more of an expert in Eastern European poetry than I am to understand how decisive a break from poetry in her language and in other Eastern European languages such poems would have seemed. It’s clear from a number of footnoted comments that she sees her work as an extension of some poems written in Serbo-Croatian and a challenge to others. Dedicated readers of English-language and American poetry will recognize some shared metapoetic concerns with writers like Wallace Stevens and William Bronk. Additionally, it’s also possible to see connections to the work of a lyrical European avant gardist like Austrian Friederike Mayröcker, who, in a differently unique manner highlights the idea of experience as constructed through language. For Djurić, the North American language writing movement has been a particularly fruitful ground of connection around the political nature of language. Oddly enough, her poems in these late '80s collections seem more directly metapoetic than much of the North American language writing of that time.

The second identifiable major shift in Djurić’s work, perhaps the most significant and emotionally powerful in this book, appears in Traps (1995) and All Over (2004). In these collections, Djurić’s concerns with the possibilities and limitations of language collide into the crisis of the Yugoslavian civil war with its nationalist and ethnocentric violence. The war, characterized by “ethnic cleansing” reminiscent of Nazi practices, was particularly evident in the rhetoric and actions of the violent nationalist Slobodan Milošević. His regime, which shared his brutal goals, lasted more than a decade; Milošević was not overthrown until 2000.

How can poetry that resists being naive about the limitations of language confront war and the human and material destructiveness that comes along with it? How can it deal with the brutal notion that some groups of people should be “cleansed” of the existence of culturally differing others? How can poetry that highlights the contested nature of language, rather than the direct physicality of experience supposedly unmediated by language, respond to the problem of political atrocity?

A book of poems and brief narratives about the same conflict, written from a different cultural environment than Djurić’s, Sarajevo Blues by Bosnian poet Semezdin Mehmedinović (first published 1992 and translated into English by Amiel Alcalay in 1998), shows the extent to which a person mired in war and local violence is never in possession of full information. News is hard to come by, and what you see and know might be limited at any moment by the walls you find yourself hiding behind. While Mehmedinović’s book is much more character- and narrative-centered than Djurić’s anti-war poems, both share the feature of resisting showing war from a perspective of complete information developed in the aftermath of struggle.

Instead, Djurić, like Mehmedinović, opts for immediacy, limitation, fragmentation, and deflection of clear sight lines or knowledge frames. In the powerful poem “Messenger of Embers,” she writes:

Steeples of hell, fields of darkness,

Steeples-skeletons of death,

Lava lichen, ludicrous,

Shapes-shades are mounted on the ground

The cursed cordons cut out

ghosts march,

deduced to a destiny

fate and darkness

and day of judgement

welcomes them with laughter

deadly deaths

burned up, heartless, soul keepers’

you are the debtors of fate

messengers of judgements (81)

This is not information in the sense of dates and times, even of facts or people. It portrays a landscape, both of religion and history, that is shaped by death. Even what is there cannot be fully seen. The landscape is made as much of language as it is of other kinds of materials.

If one would expect that it is weapons that would be “mounted,” here the vague, partially unseen objects become “Shapes-shades,” bringers of death that cannot be perceived in either a clear totality or objecthood. Words in the poem are metaphorical, heavy with the weight of Christianity and its own history of warfare, and do not provide a clear visual picture of the landscape. Instead, the landscape is one always charged by language, of the thoughts and emotions the landscape prompts. The poem feels alive, seething. The narrator does not create an observational distance in which whatever is there can be seen in some simple sense for what it “is.” Rather, the observation reveals layers, uncertainties, shadows more than clarity. Such features represent the experience of warfare through an active sense of being in it rather than only describing it. For readers of U.S. poetry, this approach might feel similar to something like that attempted by William Carlos Williams in Spring and All (1993), in which conventional literary description is reframed as that which prevents people from seeing and experiencing what is right in front of them.

Lodged between the selections from Djurić’s two overtly anti-war books comes one of the most fascinating sections of The Politics of Hope: several poems from The Cosmopolitan Alphabet (1995) that were originally written in English or, more precisely, as Djurić says in a footnote, “composed” (83). These poems repurpose into new works language borrowed and rearranged from other books in English. The second of these poems, “The End of Eastern European Poetry,” is especially notable. It features a Serbian poet, writing in English, using lines taken from an English-language anthology of Eastern European poetry, a collage whose composition displaces in several directions the idea of what an “original language” might be. The resulting poem is a powerful reflection on translation, metaphor, and exile, the sense of always being at a distance from having a language or an experience. As the poem’s final line asserts, “the experience of exile is another metaphor” (93). To exist is to be alive between languages, between locations, with a sense of self inevitably displaced from the naive belief that a language or a place can belong to a person.

Crossing between languages continues in the poem sequence “Identiteti” in All Over. The poem, written partly in Serbo-Croatian and partly in English, features both language and visual images. It’s also one of a handful of poems in The Politics of Hope that uses multiple languages, a technique that appears again later in the collection. The use of two languages does not so much merge the languages as put them in juxtaposition with each other, showing difference and proximity rather than resolution into unity.

The poems in the final two sections of the book, works from Ka politici nade (Nakon rata) (2015), as well as the new poems translated specifically for this collection, continue Djurić’s development of the two key issues at the heart of the book: the conditions of language and crossing languages, and struggles over what it means to portray experience. The prose poem “the rule of emptiness (after the war),” begins:

“we want to develop something * but we don’t know what * we want to reach something * but we don’t know what * we want to be somewhere * but we don’t know where” (180)

The poem then takes readers on a journey through a labyrinth of the difficulties created by such conditions, ending with:

“ who are we now * everyone asked the same question * spatial and time dimensions gained new meaning and new forms and we knew the time had come for the uncertain restoration lies ahead” (182)

A potential ground for connection is developed through questioning and through moving together into new, uncertain conditions, as opposed to being found in answers and grounded material realities.

To the extent that there is any central grounding to the poems in this collection, I would say that it comes from a sense of restlessness, of constant movement. Djurić’s work locates itself not in a single position, but in the movement between several positions; not in a language, but in the tensions between languages; not in a history, or a present, or a future, but in a dynamic interaction between those concepts of time. It shows how poetry can operate as a condition of transformation, of travel, rather than as something that offers any clear sense of where one departs from or where one arrives. It’s a radical hybridity of always being in the uncertainty of the between, in which differences cannot be reconciled so much as experienced and explored in the variety of their crossings.

Still, none of the above is to say that The Politics of Hope (After the War) is a book that refuses clear political or cultural positions. The anti-war stance is clear. The refusal to accept the imposed conditions of nation states is clear. The feminism is definite, insisting on the rights of women and women artists to be viewed through lenses other than masculinist histories and metaphors. The sense that language, poetry, and experience are lodged within the problems of history is never in doubt. The sense that language is limited and unstable is contrasted by a sense of certainty that to be ethical is to acknowledge the conditions placed upon us by language rather than to look naively past them.

The book comes with a lot of contextual framing. Footnotes (many composed by the translator, presumably with Djurić’s approval) provide information about source texts and moments of composition, referring to a variety of local and global political conditions, especially including references to other poets. The problem of literature, of what it means to be a writer, was particularly difficult for poets during the years of the Yugoslavian civil war (and is one that also appears in Sarajevo Blues). Key literary figures often chose to defend and indeed extend the abuses of the Milošević-imposed ethnostate.

At times, the footnotes feel like dominant presences in the text. The Politics of Hope (After the War) reads like an annotated scholarly edition of these poems, and this effect is hardly accidental. Djurić is as well known for her scholarship, editing and translating as she is for her poetry, and it’s clear that these roles interact with each other in her work. Still, I can imagine some readers finding the scholarly apparatus a blockade to accessing the emotional power of the poems. It’s important to understand though that the fiction of access, to poetry and to language more broadly, is one of the concepts that Djurić’s work is devoted to challenging. If the result of the footnotes is that sometimes the poems, even at their most passionate, seem to stand at a bit of a distance because one must frequently glance down the page to reference contextual information, this should be understood as purposeful effect rather than an overly intrusive urge to provide documentation.

“All poetry is local,” Charles Bernstein asserts in the foreword to this book, offering the idea as a challenge to the notion of poetry as universal and timeless. This seems true to me about the composition of poems. They are written in particular times and places by people with particular histories that, as Bernstein suggests, branch out from the local in multiple ways. Yet what’s also true is that when a poem is published, or a book is sent out, it crosses from some local to some other local, from some writer to some reader with their own context from which they will experience the poem they find in front of them. A poem may always be created locally, but to get into the world, it must inevitably travel, it must cross, and in doing so it finds itself translated, never perfectly, from one context to another. The original local is always partly lost, and the poem arrives somewhere new, to be understood or not understood in ways and degrees that it cannot predict. Perhaps the local itself is best understood as a group of fluctuating conditions that have to be encountered and crossed.

The Politics of Hope (After the War) calls attention to the inevitable and fluctuating condition of crossing. Poems are always in transit, Djurić’s book shows, forming and reforming meaning across the expansiveness of their encounters in a contested, dangerous world.

•••

Photos © 2007 Charles Bernstein