Vladimir Feschenko: Charles Bernstein's experimental semiotics

Language poetry between Russian and American traditions

The new issue of NLO (New Literary Review, Russia, 168:2, 2021) features a section on American poetry edited edited by Vladimir Feschenko. Two of the essays, both machine translated, with some modification, are published here. Please consult the Russian original for accuracy.

American Experimental Poetry: The Poetics of Language and Ethnopoetics

ed. Vladimir Feschenko

- Vladimir Feschenko. From the Edtior

- Vladimir Feschenko. Charles Bernstein’s Experimental Semiotics: Language Poetry between Russian and American traditions

- Barrett Watten. Practical utopia of language writing: from the book “Leningrad” to the Occupy movement (translated from English by Vladimir Feshchenko)

- Michael Davidson, Lyn Hejinian, Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten. From Leningrad (translated from English by Ivan Sokolov)

- Ivan Sokolov. The poet is always arrested. Etude in cave colors: On Clayton Eshleman — English version at Jacket2

- Clayton Eshleman. From the book Under World Arrest (translated from English by Ivan Sokolov)

Charles Bernstein’s Experimental Semiotics: Language Poetry Between Russian and American Traditions

Beware: (human-assisted) machine translation: consult the orignal here

Vladimir Valentinovich Feshchenko (Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow; PhD in Philology, Senior Researcher). Used here with his permission.

Keywords: language writing, C. Bernstein, semiotics, poetic function, Russian-American relations

Abstract: The article analyzes the work of the American “language poet” Charles Bernstein in connection with the publication of the Russian book of translations Sign Under Test. The article provides information about the history of the Language movement in the United States and demonstrates its synchronous connections with linguistics, as well as intercultural connections and exchanges between American language writing and Russian avant-garde poetry. The analysis involves the book Leningrad, written by four authors of the Language School.

Language writing: the formation of tradition and the evolution of the movement

In one of his early articles of 1909, “The Magic of Words,” which can be considered a forerunner of the “formal revolution” in Russian theory and poetry, Andrei Bely wrote: “Mankind is alive as long as the poetry of language exists; the poetry of language is alive. We are alive” [Bely 1994: 142]. Following A. A. Potebna, poeticism and the ability of figurative word-making are ascribed to language as such. But Belyi thinks further, proclaiming in the texts of the next decade the “task of a new literature” — “poetry of the word. It is no longer a question of the poetization of language, but of the linguistic transformation of poetry itself.”

Around 1912–13, revolutionary calls for the emancipation of poetic language were heard simultaneously and independently on distant continents.

In prewar Russia, the Futurist “guileless” poets order “insurmountable hatred for the language that existed before them” (“A Slap to Public Taste”) to be honored as a right, declaring “the word as such” and “the language of the future.” V. Khlebnikov prophesies a new science, the growth of which “will allow to guess all the wisdom of language” (“The Teacher and the Student”). I. Zdanevich speaks in “Stray Dog” with a manifesto on the revolution of writing, calling for the freedom of “language suitable for art” (“On Writing and Spelling”). There, the future leader of the formal school, V. Shklovsky, makes statements about the “resurrection of the word,” speaking of “the place of futurism in the history of language.

On the other side of the Atlantic, in the United States, the founder of Imagism and Vorticism, E. Pound, proposes “to forget the old language of poetry” in the name of a new “language of intuition.” And G. Stein’s first experiments in writing “set language in motion to evoke new states of consciousness,” as the literary critic M. Dodge declares. This is how the general turn of poetry toward language marks itself in completely different literary traditions (on their breakdown). or rather, the first foray of this global turn in the twentieth century (see: [Feshchenko 2018]).

The literary experiences of Stein and Pound became two poles of experimentally oriented poetry in America. The first pole gravitated toward a strategy of minimalization: Stein’s writing is built on minimal units of language, tiny shifts, “insistent” rehearsal. The second, Pound’s pole, is linked to the strategy of maximalization: the work with a variety of linguistic means, the compositional complexity of texts, the use of different languages and dialects. This pole was also reflected in life behavior: on the one hand, Stein’s quiet solitude and literary unpretentiousness, and on the other, Pound’s political maximalism and literary expansionism. Between these two points of tension of language and the discharge of poetic currents in the most avant-garde practices of American writing of the last century took place. The lines of experimental literature leading from Stein and Pound get such names in the research literature as “disjunctive poetics” [Quartermain 1992] and “language of rupture” [Perloff 1986] (on this tradition see also [Perloff 1985; Ward 1993; Perelman 1994; Watten 2003; Bernstein 2016]; in relation to its Russian counterparts: [Probstein 2017; Feshchenko 2018; Korchagin 2018]). It is these lines that converge in the “Language School” we are interested in here, the activity of a community of poets who announced themselves in the 1970s as a new avant-garde movement in experimental literature.

Several other important figures and communities were involved in the formation of this tradition and are worth mentioning. First, there is E. E. Cummings, who almost single-handedly revolutionized American verse. This includes L. Zukofsky and the whole circle of Objectivist poets who made “factography of language” a poetic technique. W. C. Williams, the creator of the purely American type of writing (what he called the “American idiom”), was an important carrier of avant-garde ideas throughout the first half of the century. The “projective verse” of C. Olson, the metaphysical minimalism of R. Creeley (as well as the work of other members of the Black Mountain School), the “complex poetry” of J. Ashbery and other authors of “new American poetry” (so called in D. Allen’s famous anthology [Allen 1960]) contributed to the formation of Language School poets.

“The San Francisco Renaissance became both geographically and culturally an immediate ‘melting pot’ for many of the ‘language poets.’” The role of the lesser-known poet J. Spicer is especially worth noting. He was notable for the fact that for some time in his youth he was involved in academic linguistics under the tutelage of the famous structuralist Z. Harris. In particular, in his lectures he promoted the fantastic idea that language is a kind of “receiver” for the transmission of ideas from space. His career as a linguist was short, but his linguistic apparatus was later incorporated into his poetry. In 1965 he published a poetry collection called Language, the parts of which bore the names of linguistic disciplines: morphemics, phonetics, semantics, etc.; its cover mirrored the cover of the influential scientific journal Language. Spicer’s figure as a unique linguistic poet had a significant impact on language writing in the 1970s.

The Language School united not even one, but a number of communities of poets across the United States. In fact, this movement is the largest phenomenon in American avant-garde literature in the last half century. Moreover, this movement is also unique in the length of its history. With five decades of practice, it remains today the most ambitious poetic mega(and meta)current: almost all of its members remain active today. Some critics do not even call “language poetry” a group or a movement, but a trend in American, mostly, but also global avant-garde writing — a trend to highlight the linguistic production of the work-text, the materiality of the signified in poetry.

Historically and geographically, the Language School has two main centers, San Francisco and New York. On the West Coast in 1971, R. Grenier and B. Watten begins to publish their independent poetry magazine under the “deictic” name This. In its first issue, Grenier’s manifesto “On Speech” was published, immediately marking the linguistic sharpening of the new discourse. The slogan was the phrase “I hate speech,” a speech act directed against speech, but consisting of it at the same time. The status of the utterance as such, its belonging to speech or language, is called into question. The priority in this dichotomy is given to language as a space of struggle between discourses, i.e. speeches. this principle will be adopted by many of the “Language poets.”

The self-title “Language-centered poetry” appeared in 1973 in a text by another Californian, R. Silliman. On the opposite side of America later, from the late 1970s, a journal edited by B. Andrews and C. Bernstein was published with the title of the  L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E movement. As in the interwar 1920s and 1930s, the experimental poetry of the 1970s is mostly published in small journals, continuing the countercultural strategies of its predecessors. At the same time, the circle of authors who associate themselves with this movement is rapidly expanding. Neither the poets themselves nor their researchers undertake to compile a complete list of participants. “A movement without specific manifestos or official membership” is how B. Perelman defines the community, preferring the term “Language poetry” to “Language writing,” referring to the movement’s polydiscursive manifestations (the same name is used by the Canadian poet S. McCaffery). C. Bernstein breaks down the self-title with signs of equality, indicating the egalitarianism of community members: “L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E: a free association / of dissimilar identities.” And the compiler of one of the anthologies of language writing (D. Messerli) puts the term “Language Poetries” in the title, pointing out the plurality of poetics of different authors.

L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E movement. As in the interwar 1920s and 1930s, the experimental poetry of the 1970s is mostly published in small journals, continuing the countercultural strategies of its predecessors. At the same time, the circle of authors who associate themselves with this movement is rapidly expanding. Neither the poets themselves nor their researchers undertake to compile a complete list of participants. “A movement without specific manifestos or official membership” is how B. Perelman defines the community, preferring the term “Language poetry” to “Language writing,” referring to the movement’s polydiscursive manifestations (the same name is used by the Canadian poet S. McCaffery). C. Bernstein breaks down the self-title with signs of equality, indicating the egalitarianism of community members: “L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E: a free association / of dissimilar identities.” And the compiler of one of the anthologies of language writing (D. Messerli) puts the term “Language Poetries” in the title, pointing out the plurality of poetics of different authors.

“Language writing” is perhaps a more accurate term for these literary practices. They are not reducible to poetry alone, although certainly poetic discourse is paramount. The boundaries between poetry and prose, free and “unfree” verse, essay and treatise, theory and practice are fundamentally destroyed here. Many of these texts are written and read simultaneously as statements, as meta-expressions, as poems, and as critical essays. The experience of French poststructuralist theory is embodied in poetic form: a critical theory of discourse is created by a discourse of poetry. The political meaning of such writing, given the current post-Vietnam protest culture in the United States, is in criticizing dominant discourses, transforming (versioning) common speech into a unique poetic language. The essence of “Language poetry” was very accurately conveyed by A. Parshchikov, who experienced its impact: “Language” possessed natural phenomena, scientific models, our bodies, and forms of ideas that lived objectively in a special “reserve,” as in Karl Popper’s World 3. American poets were interested in language as an extender (extension) of the body, of the intellect, of new technologies. Michael Palmer spoke of poetry “marked by a quality of resistance and necessary complexity, with obligatory breakthroughs and refusals and exploratory forms.” (quoted from [Bernstein 2020: 399]). Research (professorship) is also, for “poets of language,” an important part of the project of language criticism. “Exploratory” also means “investigative.” One of the most important books of the Language School is called The Language of Inquiry. Its author, L. Hejinian, explicitly states: “poetic language is the language of inquiry” [Hejinian 1991].

“L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E” as an activity: C. Bernstein’s letter between langue and parole

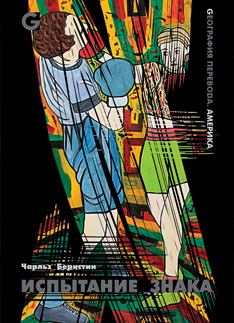

The publication of a collection of one of the leading Language poets, Charles Bernstein, in Russian translation allows us to get a comprehensive idea of the amplitudes of American Language writing on the example of one author. I have only had a handful of his articles in Russian so far, some of which have appeared in Mitya Zhurnal, Commentary, and Zvezda Vostoka in the 1980s and 1990s, in Novoye Literaturnoye Obozreniye in the 2010s, and in the anthology Contemporary American Poetry in Russian Translations (Yekaterinburg, 1996). In recent years, individual small editions of texts by M. Palmer, C. Coolidge, and R. Waldrop have appeared. Some texts were translated for the 2013 issue of the anthology Translit, which was entirely devoted to the “school of language” and included, in addition, a number of critical articles on the Language movement.  Bernstein’s book, Sign Under Test, provides the most comprehensive immersion into the textuality of the Language poet, and the translations here are by one of the best connoisseurs of the American avant-garde tradition, the Russian-American poet J. [Ian] Probstein.

Bernstein’s book, Sign Under Test, provides the most comprehensive immersion into the textuality of the Language poet, and the translations here are by one of the best connoisseurs of the American avant-garde tradition, the Russian-American poet J. [Ian] Probstein.

Of all the language poets, C. Bernstein is probably the most popular and celebrated in the widest audience. He is the author of dozens of books of poetry and essays, a university professor, academic, translator, and editor of numerous publications. His role in popularizing the sound poetic word is particularly significant. As coeditor of PennSound, the University of Pennsylvania’s audio library, and the Electronic Poetry Center, he has built up a colossal collection of recordings of poetry readings and lectures on poetry. In a sense, he is the successor of the Russian collector of sound verse, virtually his namesake, S. Bernstein. In addition, Bernstein is the author of several opera librettos. His interest in song and performance culture can also be traced in his poetic texts, often mixed on popular music tracks using DJ techniques (such as a mini-anthology of Language writing called Language Sampler).

The most characteristic feature of Bernstein’s writing technique is the hybridization of the discourses he employs. In general, many readers know him as a satirist poet, ironically playing with popular clichés, phrases, and intertexts. But this satiricality is of a high, Swiftian-Joycian literary caliber. According to M. Perloff, his poetry is “a thorough and deeply peculiar critique of contemporary half-truths, speech forms and modes of expression, and he does it so visually and with such a remarkable feeling that it takes the reader’s breath away — he laughs and cries simultaneously, shaken by recognition” (quoted from Bernstein 2020: 24).

At the heart of this linguistic satire is the clash of discourses in the arena of the poetic text. First and foremost, discourses of mass influence: political, media, military. Thus, the definitions of war in “War Stories” sounds like fragments of various discourses, from the mundane and logical-philosophical to the legal and geopolitical, with the inclusion of poetic metaphors in the midst of all this discordance: “War is us”; “War is our only hope”; “War is pragmatism with an inhuman face”; “War is the logical outcome of moral certainty”; “War is the principal weapon of a revolution that can never be achieved.”; “War is a slow boat to heaven and an express train to hell.” Ultimately, for the poet of language, war is a way of writing: “War is the extension of prose by other means” [Bernstein 2020: 177].

For Bernstein, politics has meaning as a literary fact, an action that is internalized in the text by means of words. It is a “politics of poetic form” (this, we note, is the title of one of the anthologies compiled by Bernstein in 1990), placing sociality in an aesthetic laboratory. Therefore, as the text “Truth in Pudding” puts it: “All poetics is political / All poetry is politics / All politics is poetics.” In the elegy “Concentration,” the political nominations of Poles and Jews sound like poetic meditations: “Polish Jews / Polish innocence / Jews in Poland / Jews in Polin / Polish Jews in Poland / Polish Jews in New Jersey / Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland / Poles in New Jersey / Jewish innocence / Jew in Nazi-occupied Polin / Jewish guilt / Jewish Poles / Catholic Poles / Polish Catholics in New Jersey / Poles who are white” [Bernstein 2020: 354–355].

According to R. Barthes, writing, especially “in the zero degree,” is a “morality of form”; it itself carries an ethical and, therefore, a political charge. The very language of such writing produces a semiotic revolution. Bernstein’s writing is of the same kind. Its syntax is often complex, unreadable. Sentences and words can be broken up by line breaks in the most unexpected places, making it difficult to read and stopping one’s perception at every seemingly

Give me water & I will learn to

swim. Give me hunger & I will

learn to starve. Give me sustenance

& I will learn to survive. & the

people heard & saw & wept that this

had come to pass. & so it was told

& told from one time to another, from

person to person & book to book.

& there was a rending & a crashing &

a gnashing of all things, living and

not living. When the one or many

spoke, there was all manner of dis-

location.

[Bernstein 2020: 93 “The Manufacture of Negative Experience”]

The length of a line varies from Whitmanian (sometimes not fitting into a line) to Cummingsian (down to a single character). The range of poetic means and techniques is virtually limitless. The selection of texts for the Russian edition allows us to appreciate this variety of formats and techniques.

The translator and author of the preface to the collection I. Probstein notes that Bernstein’s main poetic tool is “razor-sharp language.” If one takes this metaphor literally, such Language writing is indeed sharpened to tear through the smooth surfaces of everyday speech, it often physically “cuts the ear” with a disharmonious heap of syllables. But language is “sharpened” here in another sense: in its witticism, sometimes almost “Joyce-like” and “Pound-like,” aimed at ridiculing words, discrediting discourses. Language here is “on the cutting edge” of the criticism of the poetic gesture. Such poetic language is always dialogical, dialectical, diagonal in relation to other utterances: “Poetics is valuable insofar as it can generate other points of view, both agreement and disagreement, in response” [Bernstein 2020: 17]. In this sense, such poetics is the poetics of a direct statement placed in a poetic situation.

From his earliest texts, Bernstein’s creative task is to incorporate all the non-poetic into the poetic space, to subordinate all the functions of language to the function of poetry. The sequence of “sentences” in the early text “Sentences” from the cycle Parsing are phrases torn out of someone’s direct speech, sketched on the page (Bernstein 2000: 33–58). Once in the space of the text, these phrases inevitably become lines and make themselves read paradigmatically, forming a poetic unity.

Here it is worth noting how important for Bernstein and his circle the scientific concept of  R. Jakobson was in the 1970s. Not only in its genetic connection with the extremely important for them formal school, but also in its updated version, expressed in the famous article “Linguistics and Poetics.” The linguist was prompted to write this article by a polemic with another famous scholar, N. Chomsky. Unlike the American generalist who considered only the “grammatical” state of language and shifted “agrammatisms” out of language, Yakobson advocated a special “poetic grammar” as part of “poetic language” which, in its turn, is a functional variety of language in general. Citing examples of agrammatisms from D. Burluke and E. E. Cummings, he was not trying to take such anomalies out of linguistic interest, but rather to focus the attention of linguists on how the poetic function works in contrast to other communicative functions. The most important tenet of this theory was, as in the distant 1920s, to “turn the word on itself,” but now with an eye to modern theories of communication.

R. Jakobson was in the 1970s. Not only in its genetic connection with the extremely important for them formal school, but also in its updated version, expressed in the famous article “Linguistics and Poetics.” The linguist was prompted to write this article by a polemic with another famous scholar, N. Chomsky. Unlike the American generalist who considered only the “grammatical” state of language and shifted “agrammatisms” out of language, Yakobson advocated a special “poetic grammar” as part of “poetic language” which, in its turn, is a functional variety of language in general. Citing examples of agrammatisms from D. Burluke and E. E. Cummings, he was not trying to take such anomalies out of linguistic interest, but rather to focus the attention of linguists on how the poetic function works in contrast to other communicative functions. The most important tenet of this theory was, as in the distant 1920s, to “turn the word on itself,” but now with an eye to modern theories of communication.

Jakobson’s article did not, however, have a serious impact on American linguistics, having resonated more in the Soviet science of language of the following period (the line of “Language poetics”). But for the poets of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E group, it has become almost programmatic. In his book of essays, Pitch of Poetry, C. Bernstein notes that among linguists he was most influenced by Jakobson with his concept of poetic language as “a verbal language which puts its material (acoustic and syntactic) features in the center, ensuring that poetry is not so much a message transmitter as a medium of verbal language itself” (Bernstein 2016: 80).

Jakobson’s article itself appeared on the wave of the new linguistic turn in the humanities — the communicative-discursive paradigm. In the 1950s the theory of discourse (including poetic) by A. Benveniste and Z. Harris, the theory of speech acts by J. L. Austin, the theory of communication by G. Bateson, C. Shannon, and N. Wiener emerged. In contrast to the previous, structuralist paradigm, the new theories substantiate the view of language as an event phenomenon placed in a communicative situation. Apparently, largely through the French reception of this “new wave,” another round of the linguistic turn affects the emergence of “Language poets” in the United States. In the same years, let us note (1970s), a similar drift towards “critique of language” can be observed in European conceptualism, especially in the activities of the British art group Art and Language. In our view, all these cultural practices mark a new, action-pragmatic phase of the linguistic turn.

Bernstein is not interested in language as mere form or structure (although both its formal and structural features are certainly exposed). What matters to him is language as an arena for the collision of discourses. Including the clash of language and metalanguage, description and metadescription. How far can poetry uncover the gap between reference and sign, between intentional and extensional? To expose not just the techniques, but the very skeleton of language as an articulation of speech fragments. Not Chomskyan “deep structures” as scientifically constructed systems, but linguistic particulars, as the “Palukaville” text says: “Truthfulness, love of language: attending its telling” (Bernstein 2000: 146).

What does language provide for the poet of language and how does he/she/they (and the poet and the language) end up in the poem? To the poet language is given as a whole, and not by some chains of speech, as in other types of communication. This was realized already by the Russian Futurists and, mainly, by Khlebnikov; in prose Joyce came to the same thing. According to C. Bernstein, the Language writer is “linguistic” because he deals with the totality of language. Poetic practice here is akin to Khlebnikov’s “explosions of the deaf-mute strata of language”; it is panlinguistic, that is, sensitive to all the fibers of the linguistic organism and to all its interstitial connections, about which the ordinary speaker does not care.

One of Bernstein’s calling cards is “Ruminative Ablution,” which begins with the words: “I’ve got a hang for langue but no truck with / Parole.” [Bernstein 2020: 106]. From the Saussureian dichotomy, it is the langue that is chosen, i.e. the system, often not felt by the speaker, but which determines the rules for the choice of linguistic elements. What we hear in the street is speech (parole). When it enters the poetic text, this speech becomes internal, connected at the level of the whole. This is, on the one hand, the moment of Heidegger’s transition from talk (“chattering”) to “language as the house of being” and, on the other hand, the Benjaminian translation from “language of things” to “language as such.” Parole is centrifugal, langue is centripetal: “Because the centripetal questions the speech-force of language” (speech is the “red herring” of verse, the secret of the poem’s delusions), because, then, a poem has, by language, evanescence, nothing that can be mistreated as solid, objectified, thinged,” Bernstein writes in a text on “Introjective Verse” [Bernstein 2020: 391].

So, the main conflict in this poetry is between speech and language, or rather, between language and discourses (as forms of speech). Poetic language resists non-poetic discourses. If speech is always “too human,” language serves as a jumper between subject and object, subjectivity and objectivity. Therefore, the question “Whose language?” turns here into the relative complement “Whose Language?” (this is the title of one of Bernstein’s texts, without the question mark). What matters is not the subject, the speaker of the language, but the relationship between the subject and the predicate within the string and the text:

Only the real is real: the little

girl who cries out “Baby! Baby!”

but forgets to look in the mirror

— of a . . . It doesn’t really

matter whose, only the appointment

of a skewed and derelict parade.

My face turns to glass, at last.

[Bernstein 2020: 50].

The meeting point of speech (parole) and language (langue), according to Sausurian teaching, is the linguistic activity (language). L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, according to Bernstein, is the poetic meeting of language with speech in the activity of writing.

“Sign Under Test”: The Poetics of Extraordinary Language

Bernstein, on the one hand, continues and develops the tradition of American Objectivism and its emphasis on subjectlessness, from Zukofsky to Olson.  Zukofsky is probably his most significant figure. He is even partly close to him biographically: both poets come from Jewish immigrant families from the Russian Empire (but no longer speaking Russian). Bernstein compiles collections of Zukofsky texts and writes prefaces to them. The main thing for him in this continuity is the openness to things in language and the material perception of language. The subject falling into the verse becomes a statement of itself: “For all their differences, / each seemed crammed with possibilities, / with utterance.” (Bernstein 2020: 97).

Zukofsky is probably his most significant figure. He is even partly close to him biographically: both poets come from Jewish immigrant families from the Russian Empire (but no longer speaking Russian). Bernstein compiles collections of Zukofsky texts and writes prefaces to them. The main thing for him in this continuity is the openness to things in language and the material perception of language. The subject falling into the verse becomes a statement of itself: “For all their differences, / each seemed crammed with possibilities, / with utterance.” (Bernstein 2020: 97).

Zukofsky advocates a special attitude of exceptional fidelity to the words in the poem and to the facts recorded by that poem. He refers to frankness (in the double sense of “honesty” to the facts and “openness” to the world of things) as “a wordiness that is not a mirage but a detailing of vision, of thinking together with things as they are and guiding them along a melodic line” [Zukofsky 2018: 246]. Objectification, as Zukofsky says in the same program text, occurs in “writing (audibility in the two-dimensional space of print) that is an object or acts on the mind like an object.” It represents “the organization of the smallest units of revelation into a single unit of perception” — in other words, the resolution of words and the ideas behind them into a structure. If revelation is the poet’s ideal compositional mode and consists in the very combinations of words generated by this mode, then objectification consists in the structuring of the whole into which such “tiny units of revelation” are resolved. Objetivism of language, not description of facts, is the same principle held by Bernstein: “A fact is a frozen state of affairs. If I had to stipulate the facts of the poem, I would say there are no facts other than the words, and the words are not facts at all but what makes facts possible. The poem is the fact of its own making. The poet is the extension of the fact of the poem.” [Bernstein 2020: 198].

On the other hand, Bernstein, for all the linguistic complexity of his poetics, no longer has the kind of total trust in language that Zukofsky, Resnickoff, and W. C. Williams retain. In Recalculating (translated somewhat redundantly as “reconnecting” — for our taste, one could do without “re”) there is a conceptual metaphor of language as an albatross: “Language is an albatross, a sullen cross, a site of loss” (Bernstein 2020: 292) (in the original, more musical soundscape: “Language is an albatross, a sullen cross, a site of loss”). Is it not in the sense that language has too little room to store all the diversity of life? But the poetry of language, which, according to Bernstein, is written “in language and for language” (“Today Is the First Day of the Rest of Your Life”), is salutary for language itself, because it compresses all experience into a tight archive of verse.

Poetry, says the text “Sign Under Test,” is “a traditional form of unconventional thought” (“Poetry is patterned thought in search of unpatterned mind”). Linguistic poetics is also characterized by attention to conceptual metaphor as the operator of linguistic thinking. It is no coincidence that Bernstein is close to the cognitive linguist G. Lakoff, who participated in some actions of language poets and was involved in the problem of poetic metaphor as a cognitive scheme in the 1980s (see his book [Lakoff and Turner 1989] and his essay on language poetry [Lakoff 2013]). There are two poems about “pudding” in the Recalculating cycle: “Truth in Pudding” and “How Empty is My Bread Pudding.” The second is dedicated to the linguist himself, and its title refers to his concept of container metaphors. Both texts are a collection of aphorisms that are akin to spatial cognitive metaphors, such as about poetry as a terrace: “Imagine poetry as a series of terraces — some large, others no bigger than a pinprick — overlooking the city of language” [Bernstein 2020]. For Bernstein, metaphor is often conceptual, that is, it does not simply link two dissimilar entities, but links them in the act of thinking, in the act of writing itself. Similarity as the basis of ordinary metaphor is called into question. The metaphor here is constructed as a parataxis: “the blame is like the blame / the guilt is like the guilt / the quilt is like the quilt / the blank is like the blank / the end is like the end / the loop is like the loop / the there is like the there / the here is like the here / the how is like the how / the now is like the now” [Bernstein 2020: 197]. Yes, the metaphor itself is subjected to metaspace: “There ain’t nothing like a metaphor / nothing in this world. / There ain’t nothing you can name / that is anything like a metaphor.” R. Jakobson noted in the article already mentioned how the poetic function of language differs from the metalinguistic function: “One might argue that metalanguage also uses equivalent units when forming sequences, when synonymous expressions are combined into sentences asserting equality: A = A (“A mare is a female horse”). However, poetry and metalanguage are diametrically opposed to each other: in metalanguage sequence is used to construct equalities, whereas in poetry equality is used to construct sequences” [Jakobson 1975: http]. It is meant that metascientific utterances (such as dictionary definitions) establish on the syntagmatic axis the identity of different object names (as in the above example of “mare”), while poetic utterances place on the syntagmatic axis similar names from a single paradigm (as, for example, in the poem by V. Khlebnikov’s poem “Oh, laugh laugh, laugh” [“Incantation by Laughter”], where both the sounds and the roots of the word “laugh” are similar). However, as a number of recent linguistic studies have shown, metalanguage and metalanguage reflection have become an organic part of poetic language, beginning with the literature of the avant-garde [Fateeva 2017]. An example of this is the phrase from the poem of G. Stein “Rose is a rose is a rose,” in which both principles of statement construction are implemented.

In the texts of the Language School poets, especially by Bernstein, the poetic and metapoetic functions are often combined within a single text or even a single utterance-string. This principle generates a cross-cutting self-reference and metatextuality, as in the text “This Line”:

This line is stripped of emotion.

This line is no more than an

illustration of a European

theory. This line is bereft

of a subject. This line

has no reference apart

from its context in

this line. This line

is only about itself.

[Bernstein 2020: 75]

Like Stein’s “rose,” tautology turns to metalanguage itself: “Sometimes a sentence is just a sentence.” Recursion is an effective tool for constructing a text, or even the title of a text (“Thinking, I think, that I think”). The self-referral of a statement becomes both the plot and the constructive principle of textual construction, as in the verse “Talk to me,” in which the Beckettian scene of the self-sentence of the subject of speech from speech itself is played out. The recursion is now increasing, then it is disrupted by discontinuous repetition:

What time is it now? What time is it NOW? What TIME is

it NOW? ….

What time is it now?

TALK to me!

I don’t wanna hear what you’re saying!

SHUT UP!

[Bernstein 2020: 221]

Bernstein’s “insistent repetitions,” with which Stein’s writing is peppered, do not sound rhythmic; they set up an arrhythmia in which the repeated units put the reader into a stupor, deceiving his rhythmic expectation. Often these are repetitions — overlaps, as in “War Stories.” Strange as it may seem, the texts of the author which are formally written in prose are more rhythmically organized: in a line, not in a column.

In the text “In Place of a Preface a Preface,” the principle of chain negations “not A, but B, not B, but C” makes of some logical reasoning a recitative, turning into a mantra:

In the text “In Place of a Preface a Preface,” the principle of chain negations “not A, but B, not B, but C” makes of some logical reasoning a recitative, turning into a mantra:

As if to create not scales but conditions, not conditions but textures, not textures but projects, not projects but brackets, not brackets but bracelets, not bracelets but branches, not branches but hoops, not hoops but springs, not springs but models, not models but possibilities, not possibilities but plights, not plights but perceptual encounters, not perceptual encounters but live experience, not live experience but three-dimensional conundrums, not three-dimensional conundrums but philosophical buildings, not philosophical buildings but blind spots, not blind spots but virtual structures. [Bernstein 2020: 76]

Bernstein calls his way of writing “echopoetics”: “I always / hear echoes and reverses / when I am listening to language. It’s / the field of my consciousness.” [Bernstein 2020: 340]. Echoes as the return of the same, reflected in the other or, by fractal self-similarity, in the self itself, model the text at all levels: from sound and lexical repetitions to quotation-cicades, stridulating on motifs of world culture. It is the same and at the same time not the same as in the title text “The Kiwi Bird in the Kiwi Tree,” in which homonyms are set as tautology, or in the repetitive text “Fold,” where the conversion of names and verbs sets “doublets” at the level of syntax: “I pet my pet, I fear my fear.” Echopoetics, Bernstein explains, is “the nonlinear resonance of one motif bouncing off another within an aesthetics of constellation. Even more, it’s the sensation of allusion in the absence of allusion. In other words, the echo I’m after is a blank: a shadow of an absent source” [Bernstein 2016: 9]. The postmodern sensibility embodied in the verse; the reflection of loss: “Reality is usually a poor copy of the imitation. The original is an echo of what is yet to be” (“Me and My Pharaoh”). The dichotomies of irony and sincerity, creativity and noncreativity are removed: “The kind of poetry I want denies the binary of irony and sincerity”; “American poetry suffers from its lack of / uncreativity. I have no faith in faith, or hope / for hope, no belief in belief, no doubt of doubt.” [Bernstein 2020: 338].

Another opposition neutralized in Bernstein’s letter is between poetry and theory, diction and dictum. Never before in the history of Anglo-American literature has poetic theory merged so tightly with the poetic text, and critical discourse with poetic discourse. This is characteristic of “Language writing” in general, but in Bernstein it is actually the ubiquitous practice of not distinguishing between poetic and theoretical discourse. One could call this writing a “poem-essay” (as in [Smith 2020]), but it is specifically poetic essayism, with nonlinear vertical and diagonal connections, on the seal.

The work Artifice of Absorption, part of which, under the title “Meaning and Artifice,” is included in the Russian collection, is one of Bernstein’s most famous texts. A. Parshchikov, who took part in its translation and wrote the foreword, calls it a “tract poem” or a “scholarly poem.” According to Parshchikov, this text is a manifesto for the author’s poetics and is “a kind of constructivist poem where the ‘real,’ documentary material is the poet’s reflection on the meaning of reception in verbal art” (cited from [Bernstein 2020: 400]). Examples of such self-descriptive manifestos can be found in the Russian avant-garde, in I. Terentyev or A. Chicherin. Although for Bernstein himself the precedent text in this hybrid genre is, of course, L. Wittgenstein’s Tractatus.

The work Artifice of Absorption, part of which, under the title “Meaning and Artifice,” is included in the Russian collection, is one of Bernstein’s most famous texts. A. Parshchikov, who took part in its translation and wrote the foreword, calls it a “tract poem” or a “scholarly poem.” According to Parshchikov, this text is a manifesto for the author’s poetics and is “a kind of constructivist poem where the ‘real,’ documentary material is the poet’s reflection on the meaning of reception in verbal art” (cited from [Bernstein 2020: 400]). Examples of such self-descriptive manifestos can be found in the Russian avant-garde, in I. Terentyev or A. Chicherin. Although for Bernstein himself the precedent text in this hybrid genre is, of course, L. Wittgenstein’s Tractatus.

Some critics, such as M. Perloff, have noted the “poetic nature” of the great Wittgenstein’s early philosophical experiments (Perloff 2011). Wittgenstein himself admitted in private correspondence that the Treatise was both a strictly philosophical work and a literary text. And he even tried to publish it in a literary journal. Referring to Wittgenstein’s phrase “Ich glaube meine Stellung zur Philosophie dadurch zusammengefaßt zu haben, indem ich sagte: Philosophie dürfte man eigentlich nur dichten,” Perloff analyzes some excerpted texts by Wittgenstein as protopoetic. A diary entry, she notes, can be considered a kind of protostructure of a poetic text, and it is not a fantastic task to consider, for example, the Tractatus as a quasi-poetic text.

Bernstein turns this task inside out, trying to write treatises in verse, philosophizing in vers libre. Wittgenstein is important to the American poet both academically and practically. As a student, he wrote an undergraduate paper on “The Three Steins,” referring to G. Stein, Wittgenstein, and himself (and would later write a poem, “Gertrude and Ludwig’s Bogus Journey”). Later, under the guidance of the famous philosopher of language S. Cavell, he would defend a thesis in which he amalgamated the positions of analytic philosophy and avant-garde writing. His own poetic texts, such as “Language, Truth, and Logic” from Girly Man, are also based on Wittgenstein’s themes, and his quotations are incorporated into the poetic treatise Artifice of Absorption:

Do

not forget,” says Wittgenstein in a passage quoted

by Forrest-Thomson, “that a poem, even

though it is composed in the language of

information is not used in the language game of

giving information.” She adds that “form and

content are [not] identical, still less are they

fused … they must be different,

distinguishable in order that their relations may

be judged.” [Bernstein 2020: 121]

I’ve got authenticity, you’ve got dogma … proclaimeth the Lord.

Saying one more time:

It’s true but I don’t believe it

I believe it but it’s not so.

“My logic is all in the melting pot.”

[Wittgenstein]

[Bernstein 2020: 339].

Wittgenstein as a writer was also admired by L. Zukofsky, who himself once wrote a short treatise-commentary on his poem “The Mantis” in verse form. For Bernstein, the linguistic turn in American poetry is associated primarily with Wittgenstein, with his ideas about how we operate on reality through language. The philosophy of ordinary language inspires the “poet of language” to create a language that is extraordinary as a product of the “pataquerical imagination.” The notion of pataquerical, as J. Probstein notes includes both “queer” and “quest” at the same time.

Search, test, experiment are of course very frequent words in Bernstein’s vocabulary. Language writing is difficult to imagine outside the experimental tradition in literature. Language on entry is a test for the author of Language poetry; language on exit is a test for the reader of it. “Sign under test” — a literal translation of this title of Bernstein’s poem would sound “Warning: sign under test.” Such signs are put up wherever temporary work is being done to test electronic placards. The Russian title, however, given by the translator to the entire collection, is more succinct and metaphorical: “The Test of the Sign” is both a test of the “sign” and a test of semiotics. Note that Zukofsky uses a similar formula in the title of his book A Test of Poetry. Bernstein’s writing appears as a kind of “test semiotics,” a “bent” creative and critical theory-practice of sign processes (“bent studies”) whose task is to “move beyond the ‘experimental’ to the untried, necessary, newly formed, provisional, inventive” (Bernstein 2020: 339). The syntax of language writing is a crucial dimension of testable, exploratory, avant-garde semiotics: “The business of poetry is not to put syntax back into the cage, / but to follow it on its way to the unexamined.”

In Search of Poetic Function: The Russian-American-Russian Transfer

The last quote seems to echo the lines of V. Mayakovsky. Mayakovsky’s lines about poetry as “riding into the unknown.” The poetry of the Russian Futurists is hardly the main foreign source of inspiration for C. Bernstein and his circle (along with O. Mandelstam, A. Bely, B. Pasternak). Not only because of the formally experimental nature of Futurism, but also because of the political, revolutionary power of its poetics. And also, the “poets of language” are fascinated by the closeness that unites the Futurists with the theorists of poetic language, the Russian formalists.

V. Khlebnikov is mentioned most often, among Russian poets, by Language poets. He is dear to Bernstein for his ability to transform the boundaries of language and languages in “abstruse poetry,” his search for a universal language. Along with Joyce, Wittgenstein, Mallarmé, Beckett, he believes Khlebnikov is one of the heroes of the “linguistic turn” in the twentieth century. The “breakthrough into languages,” carried out by the Futurians, brings poetry to the level of world-transforming knowledge and thinking, to which American poets also aspire.

Bernstein’s poetry itself, however, bears little resemblance to the Khlebnikovian language project. There is almost no word-creativing in it, no rationalistic attempt to create a new “alphabet of the mind.” Rather, zaum (in one of the English translations of transsense) is practiced as a transgression of discourses, in the words of J. Probstein, “it is the search for meaning behind popular stereotypes, so-called common sense or official political rhetoric” (cited from: [Bernstein 2020: 10]). This is Khlebnikov filtered through the language games of Wittgenstein and the discursive matrices of Barthes-Foucault-Van Dijk.

The Khlebnikovian trace becomes more visible in the Russian translations of J. Probstein. Especially where the word-formation creativity of the recipient language comes into play. The poem “Fold” is translated not as “fold,” but as “hinged icon,” alluding to the Russian tradition of iconography. English tautologies such as “pet my pet” are transformed here into root interjections of different parts of speech: “petting my pet,” “torturing my torture,” “twisting my rope.” Nonexistent but potential words are also used, such as in “I quiet my [silence],” “I name my [name],” and “I uncloak my weather.” Neologisms in other texts, such as “affirmation” or “transsegmental swimming,” remind us of the Khlebnikovian principle of “grief.” Bernstein’s translator does an important work of cross-pollination between the two languages — not a simple tracing, but a poetic transformation of the text in another language. English and Russian differ not just in their structure (analytic and synthetic), but also — in their poetic function — in the principle of text production. This is well understood by “Language poetry” in translations: Russian translator L. Hejinian explains this radical difference not only by the movement of thought, but also by the foundations of thinking itself: “American English is a ‘wide’ language with enormous horizontal freedom, and Russian is a ‘deep’ language with enormous vertical freedom” [Hejinian 2013: 65]. In the interlingual English-Russian transfer, “breadth” resonates with “depth,” opening up new dimensions of expressiveness.

In Bernstein’s early collections (not represented in the Russian translation) there are still texts with formal intricacies: typographic games (“ElecTric,” “Lift Off”), twisted, unreadable nonsense with Poundian allusions (“Azoot D’Puund”). Some glimmer of these typographical constructions can be seen in the verse “Dea%r Fr~ien%d,” 2013, which mimics glitches in computer typing. However, the linguistic anomalies here are part of a conceptual verse performance rather than examples of sound writing. The closest analogy to such experiments should be sought in American literature itself — in the graphic experiments of E. E. Cummings or in the half-forgotten verse compositions of A. L. Gillespie in the 1930s. This kind of experimentation is only one of the many conceptual techniques employed by Bernstein. Sonoric experiments as such, strange as it may seem for his interest in sounding verse, do not follow him.

Other Russians who have influenced his writing, by Bernstein’s own admission, include avant-garde artists: Malevich, Rodchenko, Kandinsky (both as artists and as authors of texts). The key term important in this reception is texture. For Bernstein, it is the creation of verbal objects for reflection. Facture is what allows us to see form and function in their conjunction, the reflection on poetic reception as the realization of reception itself. The development of the theory of texture and form as such by Russian formalists had no less influence on language writing than formal poetry itself. What M. Perloff called the “Futurist moment,” referring to both the chronological (moment of time) and the physical (moment of force) meaning of the term “moment,” is “the emblem of the most radical moment of the avant-garde period” (Bernstein 2016: 64).

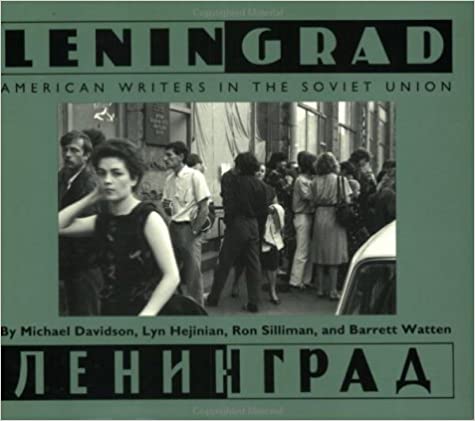

Russian Formalism is cited by all the main representatives of the “Language School” as one of the first and most important reference points for their own poetics. For example, many references to its legacy can be found in the collective travelogue book Leningrad.  M. Davidson admits that formalism was a “treasure trove” of the theory of the language school. The formalist school is associated here with a particular Russian approach to the poem as an object. Whereas in the American tradition Objectivism was only an episode in the activities of a small group of poets (Zukofsky, Oppen, Rakosi), Russian theory gave birth to an entire scientific school of object analysis of artistic structure: “The union of two projects — let us call them scientific and cultural — around poetics develops into a kind of myth of the object, whose supreme significance consists in its transcendental nature” (Davidson et al. 1991: 37). Even in the pictorial experience of the scientific dilettante Malevich one can see this fusion of scientism and subjective poeticism, resulting in a scientific religion of form.

M. Davidson admits that formalism was a “treasure trove” of the theory of the language school. The formalist school is associated here with a particular Russian approach to the poem as an object. Whereas in the American tradition Objectivism was only an episode in the activities of a small group of poets (Zukofsky, Oppen, Rakosi), Russian theory gave birth to an entire scientific school of object analysis of artistic structure: “The union of two projects — let us call them scientific and cultural — around poetics develops into a kind of myth of the object, whose supreme significance consists in its transcendental nature” (Davidson et al. 1991: 37). Even in the pictorial experience of the scientific dilettante Malevich one can see this fusion of scientism and subjective poeticism, resulting in a scientific religion of form.

B. Watten often refers to Russian formalism in his scholarly writings (Watten 2003). The notion of literariness as made is projected onto contemporary poetics not so much as an aesthetic principle, but as an ethical imperative: “Shklovsky’s notions — ‘word processing,’ ‘defamiliarization,’ ‘semantic shift’ — seemed to us not just a matter of art, but a matter of ethos: the meaning of creative action in some context (literature, society) which cannot be fully represented” [Davidson et al. 1991: 28]. Russian poets encountered by Americans in the late 1980s in the USSR seemed to ostracize their own tradition of defamiliarization. In Late Soviet Leningrad, poets of language experience the city of OPOYAZ in its “formal contours” as a lived rather than a represented experience. OPOYAZ serves as a model of a utopian “marriage alliance” between the American and Late Soviet avant-garde: “Russia offered the ‘imaginary community of intellectual friends’ necessary to realize this utopian goal, just as earlier this community served as a model for the utopian project of ‘Language poets.’” [Edmond 2012: 75].

C. Bernstein is also fond of quoting Shklovsky, especially his idea of defamiliarizing reception. One of the song poems is titled with an explicit reference to Russian formalism through an even more explicit intertext with M. Duchamp: “Ballad Laid Bare by Its Devices (Even): A Bachelor Machine for MLA.” Another text, more drawn to the treatise, Artifice of Absorption, is also inspired by the formalist concept of reception as defamiliarization. According to A. Parshchikov, this “tract poem is itself replete with a demonstration of the techniques it describes” (Bernstein 2020: 402). Bernstein’s key term Artifice (reception, sophistication, artificiality) echoes the title of Shklovsky’s manifesto in English, Art as Device.

The neo-formalism of U.S. language poets was not the result of a doctrine directly adopted from the Russians, but the fruit of a cultural transfer of formalist notions through a different culture and in a different chronotype. The form here was no longer a flag of revolution but placed in the neo-avant-garde tradition as a countercultural critique of art. Bernstein writes about form in places with a grin, twisting C. Olson’s famous postulate from “Projective Verse” about form as “nothing more than an extension of content:” “It is this: FORM IS NEVER MORE THAN AN EXTENSION OF MALCONTENT. There it went, flapping, more USELESSNESS.” [Bernstein 2020: 390]. In dismissing the “neo-formalists,” he calls his personal movement “nude formalism” (see his book coauthored with Susan Bee, The Nude Formalism), as if formalism were a naked bride facing her suitors from the scandalous Duchamp canvas of its time.

The poets of the “language school” were lucky enough to come into direct contact with a representative of the Russian formal school when the four of them (Watten, Davidson, Hejinian, Silliman) were invited to Leningrad in 1989. There they were able to talk to the Young Formalist Lydia Ginzburg, who read a paper entitled “The Historical Significance of the OPOYAZ.” The event they participated in was also related to one of the key Formalist concepts. The title of the conference was “The Poetic Function: Language, Consciousness, and Society,” and it was organized by A. Dragomoshchenko, then chairman of the “creative program” at the Soviet Cultural Fund, which was called “The Poetic Function.” This meeting was almost the first ever between Russian and American poets and bridged (and, considering the Leningrad context, brought together) the two poetic traditions, and in their experimental offshoots.

By that time some Language School poets had already visited the USSR unofficially, but this time the visit was quite official, sanctioned by the state. However, the main thing that happened at this conference was communication between representatives of the American “language” trend in literature and representatives of the two leading schools of unofficial Russian poetry — metarealism and conceptualism. However, the metarealists dominated:  A. Dragomoshchenko, A. Parshchikov, I. Zhdanov, V. Aristov, and I. Kutik took part. The messenger from the conceptualist camp was D. A. Prigov, who was most friendly with Parshchikov and others. Different opinions exist about the closeness of “Language poetry” and conceptualism in the Russian version. L. Hejinian, for example, believes that with some formal commonalities, the two movements differ in the same way that American English and Western capitalism differ from the Russian language and Soviet communism. Metarealism appears to be a closer paradigm for Language poetry because of “a fascination with the epistemological and perceptual nature of language-thought, the belief that poetic language is a suitable tool for exploring the world, an interest in the linguistic layering of the landscape” [Hejinian 2013: 64]. According to the researcher A. Lutzkanova-Vassileva, Language writing has as much in common with Russian conceptualism as with metarealism, including due to its common roots in the Russian avant-garde [Lutzkanova-Vassileva 2015].

A. Dragomoshchenko, A. Parshchikov, I. Zhdanov, V. Aristov, and I. Kutik took part. The messenger from the conceptualist camp was D. A. Prigov, who was most friendly with Parshchikov and others. Different opinions exist about the closeness of “Language poetry” and conceptualism in the Russian version. L. Hejinian, for example, believes that with some formal commonalities, the two movements differ in the same way that American English and Western capitalism differ from the Russian language and Soviet communism. Metarealism appears to be a closer paradigm for Language poetry because of “a fascination with the epistemological and perceptual nature of language-thought, the belief that poetic language is a suitable tool for exploring the world, an interest in the linguistic layering of the landscape” [Hejinian 2013: 64]. According to the researcher A. Lutzkanova-Vassileva, Language writing has as much in common with Russian conceptualism as with metarealism, including due to its common roots in the Russian avant-garde [Lutzkanova-Vassileva 2015].

[image: Bernstein and Dragomoschenko, St. Petersburg, 2001]

What did they all have in common with their American counterparts? The answer lies in the title of the event itself: the relationship between language, consciousness, and society. The “poetic function” of language, according to R. Yakobson, related everyone to the legacy of the Russian avant-garde. But the problematic was more in line with the intellectual landscape of the 1980s. It was not by chance that Dragomoshchenko decided to also invite a number of prominent Soviet linguists to participate: V. V. Ivanov, D. Spivak, S. Zolyan, and some others. In these years, the problem of consciousness began to move to the forefront of scientific studies; cognitive approach, conceptology, linguistics of altered states of consciousness, and metaphor theory were emerging in the science of language. So the mutual interest of conceptual and metarealist poets and actual linguistics was as urgent as it was long overdue. Inviting poets of the Language School, rather than any others, was, of course, motivated by this rapprochement.

We can learn about how the conference went from the story of the American guests-poets in the book Leningrad, published in America after the trip (and also — in retrospect — in the article of one of them, which is published in this collection). Any materials of it, alas, were not published in a general form, except a couple of articles by linguists and small texts by Language poets in Mitin magazine. The fact of such a Russian-American meeting of poets is unique. Countries closed from each other for many decades discover for each other living bearers of the two great poetic cultures. An exchange of subjectivities takes place through the experience of mutual translation: L. Hejinian translates Russian metarealists, A. Dragomoshchenko — American “poets of the language.” The transatlantic polylogue makes two once irreducible traditions translatable and, moreover, mutually permeable to each other. When the problem of metalanguage is the main creative challenge for both sides, interlinguistic openings for both languages are found, following Benjamin.

Bernstein was not among those invited at the time. But now, thirty years later, the act of translating a solid collection of his poems into Russian is a continuation of those first encounters, recoding from American Language writing to Russian Language poetry and back again. What do the two poetic cultures have in common in these translations?

First, and perhaps most importantly, is conceptualism. Not so much as a movement, but as an artistic method. Strictly speaking, in the American tradition, conceptualism is a movement in visual art, and it is very indirectly related to poetic movements. Unlike the Russian situation, in which these vectors are merged into one. However, this does not prevent some American literary theorists from classifying Language poetry as conceptual writing (M. Perloff, in particular, is of this opinion). In fact, most of the techniques used by Bernstein are conceptual. There is a demonstration of the technique, and the technique is practiced performatively throughout the text. Thus, the text “Questionnaire” presents lines one by one in questionnaire form. The text “Catachresis, my love” is built on a series of catachreses. And the text entitled “Poem Loading,” as befits a conceptual move, does not contain the poem itself. Conceptuality is also the art of self-condemnation, as manifested in the text “The Lie of Art.” “I don’t want innovative art. / I don’t want experimental art. / I don’t want conceptual art” [Bernstein 2020: 317].

On the other hand, for all his rationalistic and sometimes playful conceptualism that exploits linguistic clichés, Bernstein’s prose poems also contain a great deal of inner linguistic work. In this, he is also close to the metarealists. For example, in the same text “Catachresis, my love,” we find what M. Epstein would call a metabola: “A tear in the code: the code weeps for it’s been ripped.” And yet Bernstein is perhaps the greatest conceptualist of the Language poets. “All poetry is conceptual, but some is more conceptual than others.” Conceptual in the sense in which he himself defined: “Conceptual poetry is poetry pregnant with thought” [Bernstein 2020: 269].

With the emergence of the “Russian Bernstein,” thanks to J. Probstein, we now have an important experience of the Anglo-Russian transfer of Language poetry and Language art. A transfer, one might say, that is partly the reverse, since the Language School itself has drawn much from the Russian avant-garde of the beginning of the century. This avant-garde, Russian and American (“on these continents”), seems to be the subject of the following passage from the text “Today’s Not Opposite Day.” Considering that it was written around the year 2000, “eight decades and seven years ago” falls precisely on the 1912–1913s, when the linguistic breakthrough began. And the last phrase of this speech, which is stylized by its loftiness as a political proclamation, surprisingly echoes the prophecy of the coming “poetry of language” quoted at the beginning of the article:

Four score and seven years ago our poets brought forth upon these continents a new textuality conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all meanings are plural and contextual. Now we are engaged in a great aesthetic struggle testing whether this writing or any writing so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on an electronic crossroads of that struggle. But in a larger sense we cannot appropriate, we cannot maintain, we cannot validate this ground. Engaged readers, living and dead, have validated it far beyond our poor powers to add or detract. That we here highly resolve that this writing shall not have vied in vain and that poetry of the language, by the language, and for the language shall not perish from the people. [Bernstein 2020: 110].

References

Consult list at the end of this pdf.

–