Robert Kelly and Bruce McPherson on Thomas McEvilley

Bruce McPherson read Robert Kelly's tribute to Thomas McEvilley, along with his own, at The Arimaspia launch and McEvilley celebration at the Poetry Project last week. My preface to The Arimaspia was published in Hyperallergic.

Bruce McPherson

Tonight we're presenting two new books by Tom McEvilley. First, a collection of poems translated mostly from the Greek Anthology. It's a handsome hand-set limited-edition letterpress book and its lovely formal quality contrasts with the poems' ribald profanity. Tom's versions of Meleager and Philodemus and other poets are earthy and comical laments, barely recognizable when compared against the “accurate” translations of a century ago. Following Pound's example and dictum, he makes these great old poets come alive again, makes them new, suffusing them with the very spirit and transience of Now.

Most of these poems also appear in The Arimaspia, or Songs for the Rainy Season. There, the poems are worked into one of the two main narrative streams, the one dealing with an apprentice Greek philosopher's journey to India. If I'm right that these poem translations came first, then I imagine The Arimaspia arose somehow from them like Across the Universe arose from the songs of the Beatles, a scaffolding for composition, but with a result of far greater complexity. The Arimaspia is simultaneously a novel and a poem, a mock epic and a cacophony of voices, a send-up of the Victorian novel of adventure and a post-Modern reflection on the futility of narrative. Because this is the literary counterpart to his great work, The Shape of Ancient Thought, it tells of forgotten or effaced encounters between the West and the East, between the Self, in other words, and the Other. This is a theme found in much of Tom's work, but nowhere is it more brilliantly and comically exemplified.

I'd been reading Pound's Cantos for some time before I first happened upon the recordings he made of some of them. It was a revelation. As a student I'd always read him with utter seriousness, and now there he was wisecracking and imitating voices and singing and declaiming and generally hamming his way through what I had thought was supposed to be the most serious poetry of the century.

2

In some regards The Arimaspia is a Poundian work – a transgressive work containing many voices intruding and impinging and harmonizing while narrative streams carry forward strange tales of fortitude and depravity. So tonight we thought we'd try to convey some of Tom's comedy by reading two excerpts as ensembles. These selections are from later parts having to do with a libidinous professor of classics who seduces his students, and with the itinerant philosopher's campfire poetry slams. Joyce Berstein selected and edited the group readings.

Just a few words about the publication of The Arimaspia. We were able to produce a small edition of 250 copies for tonight, in advance of a larger publication soon afterward. Think of this night, then, as a Kickstarter. We invite your help to bring this work of literary genius to the world at large.

••••••••••••••••••••

Robert Kelly: McEvilley

When you paint a girl blue and roll her on a canvas or when you paint your hand with red ochre and press it on a wall you are doing the same thing, making the same sort of thing.

The mess of meaning lasts thirty thousand years.

Nobody knows what you have in mind in doing so. But that is not important, thank God. There are people, and McEvilley was among the smartest of them, who know that once the mark gets made, it gets made in us. It lasts.

He doesn’t care about the 30,000 years that separate such marks, marks that could be generated tomorrow if there were such a thing as time.

Art doesn’t defy time. It denies time.

So art speaks to a society by itself and by the critics who help us, force us, to look at it, or intensify by their palaver the force of seeing.

Criticism can be nothing without literature — Baudelaire, Apollinaire, Ashbery, John Yau, it keeps going. But literature could be nothing without the cave-work, the isolato crazy self-encounter that gets cleaned up and publicked as philosophy.

I marvel at the breadth of McEvilley’s generosity, his insistence on tracing thinking back and forth, our Europe, their Asia, their Europe, our Asia, their hands on the walls of our mind.

I suspect McEvilley knew there was no such thing as time, only space, space of cave, canvas, display case, window, śloka, stanza, epic. What is any epic poem but a refutation of time, the whole war in your hand (as in Homer or Quintus of Smyrna).

We say of someone who has died that he has gone away. The French say ‘disappeared.’ Proof enough of the poverty of time, the richness of space, into which such animals can prowl off.

The work of his that touched me most was the novels — are the books so telling because he was a writer, one of the few I ever met, who could talk about everything?

Context was complete in him. So everything could be said. Those years of saying everything else, art, culture, poiesis, and all the while he was making his masterpiece, The Shape of Ancient Thought, that showed so clearly that we get what we think from the same place we get language, the breath of the other.

In his last novel, The Arimaspia, someone starts us off by saying that out of the primordial soup of neurological perceptions and proprioceptions someone else is trying to shape and organize a bicameral brain. Our kind. Then trying to make some sense of what he’s made: the baby god of the self, confusing his own spasmodic gestures with the movements of the planets and other wanderers.

So art is otherwise. Art is thinking with the hands and so on.

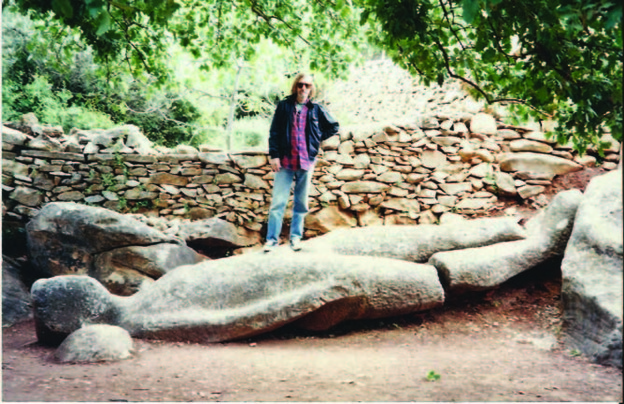

McEvilley sat in his cave in the Himalayas a long time (I forgot to ask him if he was in the Terai or the high peaks), sat there thinking by himself.

When you think by yourself, everybody thinks with you.

East and west, thinking crowds in. It can dwindle into mere thoughts or stay alive as thinking. And writing was his way of getting thinking out of the body. It might be the only cure for thinking.