George Kuchar (1942-2011 )

George Kuchar was one of the most creative, original, and influential filmmakers, straddling between two generations of North American iconoclasts, including Stan Brakhage, Ken Jacobs, Rudy Burckhardt, Kenneth Anger, Michael Snow, Warren Sonbert, Ernie Gehr, Abigail Child, and Henry Hills. Often collaborating with his twin brother, Mike, the Kuchars started making films as Bronx teenagers and these early films already show the ingenuity, exuberance, and do-it-yourself charm that they would keep over their scores of subsequent films.

George went into hospice care a few weeks ago as his cancer got the better of him. His last days were filled with visits by friens and students, with his brother Mike near by. IndieWire just published the first notice of his death.

Every year Kuchar made a large-scale scripted film with his students at the San Francisco Arts Institute, with lightening effects, costumes, and sound track, which were comparable to greatest Hollywood films, but all done on shoe-string budget. Rather than being constraining, Kuchar’s production budget enriched the aesthetic power of his films. It helped that he was something of a genius when it came to lighting, editing, make-up, cinematography, directing, musical soundtrack, and script writing, but his commitment to film as something that can be done ideosyncratically (I meant to have the ideology in there) and without huge expense has been an inspiration to a generation of independent film makers after him. Indeed, Kuchar’s films anticipate the work of younger video artists for whom cheap digital cameras and the web are the tools at hand.

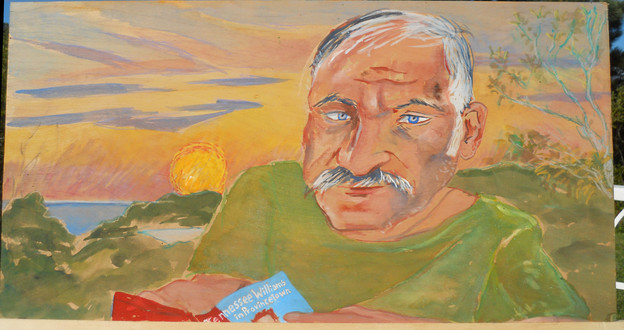

As a writer, Kuchar combined his genre-obsessed irony and self-reflective bathos into scripts of scintillating wit. The opening monologue in Thundercrack (for which he wrote the screenplay for Curt McDowell) rivals as it extends the best of Tennessee Williams. PennSound has a link to his script for The Bride of Frankenstein, which is a perfect example of his largely unacknowledged brilliance as a writer. His sound tracks, collages from his extensive LP collection, are exemplary for using already existing music in new contexts so seamlessly you would have thought the music was composed especially for each scene; in a sense, it was. Kuchar made the switch from film to digital relatively early, fully embracing the dominant technology, and as he had done with film, making it fully his own. Much of his later work consists of an ongoing dairy – a sprawling, picaresque series in which he documents the weather, his meals, his friends, his trips. These funny, endearing works, in which he is the principal character and which he shot entirely by himself, are films that revel in the sublimity of the ordinary.

Kuchar stayed true to his American vernacular instincts throughout his life. The body of work he produced, now archived at Harvard, is a testimony to the power, and importance, of film done without the hindrance of the large-scale production. A man with a movie camera: nobody’s done it better.

George came down the hill from Mimi's to the Race Road place, where last summer he filmed Susan painting and my reading from Girly Man. Last night at dinner, George was saying how much he was influenced by Tennessee Williams, which you can see more in his screenplays than in his films. He said he had once met Williams in a pool locker room, and that Williams had greeted him, possibly mistaking George for someone else. But George didn't realize who he was till just after he left.

August 11, 2007

PennSound Cinema's George Kuchar page has a number of recent Kuchar films, as well as my three Close Listening shows and Andrew Lampert's video interviews, and the script to The Kiss of Frankenstein.