Molly Weigel: Introduction to The Shock of the Lenders & Other Poems by Jorge Santiago Perednik

from Action Books (2012)

Jorge Santiago Perednik's long poem The Shock of the Lenders has been published in sections in English over a period of years, starting with "The Main Fragment," which first appeared in Sulfur in 1992, and was subsequently reprinted in The XUL Reader (Roof Books, 1997) and The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry (2009). The other sections, or fragments, of the poem, meanwhile, appeared only recently, in S/N: New World Poetics in 2010. In the present volume the poem in English appears for the first time in its entirety. This new wholeness, presented with a generous sampling of other Perednik poems from different periods, provides a new context for the work in English, and an opportunity to explore some other contexts that can help to deepen a reading of these translations and to resist an easy consumption of them as "experimental" poetry independent of language or culture.

The political moment in which the poems were written, the role of XUL Magazine, the specific story of the Schoklender murder case on which The Shock of the Lenders is based, Perednik's own views on translation, and the Argentine literary context that informed the poems, are all worth delving into. This publication twenty years after the first English publication also invites a meditation on the translation's "afterlife." Here is the whole poem in English, gathered like the limbs of Osiris. What have these twenty years done to its fragments and its body? How has it changed as its English readers, author, and translator have changed? And how might this new publication continue this process of change?

But wait. This is one way to tell the story of the translation and of the poem. But the titling of sections within the poem questions the validity of the translator as Isis. The sections of the poem are titled as fragments: "The Main Fragment," "Fragments 4 and 12," "Fragment 16," "Fragment 21," and two brief fragments, 33 and 35, which are also labeled, "From 'Diary of the Flight.'" These titles imply that the poem in Spanish was never a whole that could be divided by piecemeal publication in English and then finally reunited. The "Diary of the Flight" sections also seem to imply that these are not fragments of a single document but that there were at least two documents whose fragments now make up the poem.

Yet we readers, in English or Spanish or any other language, have long been familiar with the notion of the literary work, society, language, and our own minds as composed of fragments, never whole, certainly since Eliot wrote, "These fragments I have shored against my ruin" almost a hundred years ago. We have grown accustomed through modernism and postmodernism to read fragmented works, and ones that incorporate multiple other works, or multiple registers of language, as a call to an imagined prior wholeness that never really existed, or as an embrace of this lack of wholeness. Our strategies for reading such works as nonetheless wholes of sorts have multiplied.

Perednik's section titles thus innocently seem to address the experienced reader of fragmentary wholes, as if these titles are newly entering the dialogue without having heard the beginning of the conversation. He cannot seriously expect us to search for the missing sections, or to construct an underlying narrative whole inferred from their absence. Yet these titles' seeming innocence might also ask us as readers to explain ourselves and to reevaluate where we are in the conversation. Thus from the start, the readers of The Shock of the Lenders in English must scratch our heads. What are we as readers to be doing? Are there things we need to know about that we don't, yet? Do those seemingly innocent titles know more than they're saying?

Let me then try again to tell the story of this poem, this time starting at the very beginning (and I'll keep starting over if I need to, as many times as proves necessary). The "Fragmento principal" of El shock de los Lender first appeared in April 1983 in issue 4 of XUL Magazine, edited by Perednik, during the last year of the Argentine military dictatorship (1976-1983). During these years the military junta conducted a "dirty war" in which an estimated 9,000 to 30,000 "disappeared." While the junta justified this genocide as necessary to battle leftist guerillas, most of those at risk of being "disappeared" were ordinary citizens, including anyone who opposed the dictatorship, trade unionists, students, and artists.

Perednik has written for an English-speaking audience about the political context of The Shock of the Lenders and the political necessities that gave birth to XUL Magazine in his introduction to The XUL Reader. "Terror settles in people and affects them in unforeseen ways; in the case of Argentine poets, whatever they wrote about, even if they didn't intend to, they wrote about terror. Without the information, then, that certain poems were written during a regime of terror, a possible dimension of reading them is lost; if the fact that this experience existed and intersected the writing of the poems is repressed, access to multiple relations and a whole spectrum of interpretive paths is closed off to the reader. " Perednik wants English-speaking readers of The Shock of the Lenders and other poems published in XUL during the dictatorship to be able to use this information to read more deeply and widely, to be able to go down many paths. He invites those of us who may have been able to avoid the experience of having terror "settle in us" to meet those of us who have not.

This experience of terror, Perednik continues, gave birth to the poetry itself. In Argentina during the dictatorship, being a poet who engaged with language as a non-transparent medium that had its own materiality, and that could be experimented with, was a matter of necessity, not choice. The poets who loosely collected around XUL Magazine coincided "not in style but in the conviction that the means of resisting with art is through the how that the poems say…The poem is a significant form; in epochs of severe repression facility with the forms of saying permits escape from the vigilant gaze of the censor; as for interested readers, they become skilled: sharper, more critical. It can thus be concluded that the resistance of these poets was not the gesture of heroes, although a certain history might want to present it that way, but rather that it was their response to being placed in an impossible situation." These questions about what is being asked of the reader of The Shock of the Lenders now take on a new seriousness. In this passage, Perednik seems to say that the poet writing to resist a regime of terror needs readers who can recognize the integral meaning of the poem in and as its form, as well as beyond its form; these readers serve as a counter and an antidote to the censors who try to detect and prevent the resistance. The poem's form is a means of communication regarding that which may not be said, and the poet and the readers together create this communication that is an act of resistance.

Perednik further emphasizes that these poets' resistance was not simply theoretical; it was a matter of survival. "They walked the razor's edge…not falling into the abyss on one hand, and the abyss was the threat of dying at the hands of the repression, which killed many thousands of opponents; and not accepting, on the other hand, the security of firm ground, that is, poetic renunciation or temptation to the various forms of complacency." In other words, by communicating about being under repression, they themselves risked being disappeared; if they did not communicate in this way, they risked compromising their integrity as poets and humans. In order to survive, they needed to write about it in such a way that they would not be detected by the censors. However, they also needed a community to survive--they needed to write in such a way that they could be detected by their readers, who needed to read in such a way that they could receive the communication. This is a conversation that English-speaking readers of The Shock of the Lenders are now being asked to join.

It might be fruitful to look at how this Argentine poetry both resembles and differs from a North American poetry which has a similar project of foregrounding experimentation with language as a way of making meaning, but which does not have the same pressure to communicate in a dangerous situation. What is the relation, for example, between including multiple registers of language in a poem and creating a language of veiled but specific political references? The disruption of univocal meaning and the need to assert what might otherwise remain unsaid may sometimes exist in productive tension. The exploration of this tension could be fruitful in interpreting other texts across national boundaries.

The Shock of the Lenders also evokes the nineteenth-century Argentine tradition of gaucho poetry. The gaucho poets were Argentines of European ancestry who wrote in the voice of indigenous gauchos to articulate their opposition to the violent repressive regime of Manuel de Rosas. The use of a different language or dialect to express what couldn't otherwise be expressed thus has a long history in Argentine poetry. In The Shock of the Lenders, the treatment of the brothers fleeing on horseback evokes the stirring narratives of battle and flight on horseback in the gaucho poems. But in The Shock of the Lenders, the national narrative of heroism that gaucho poetry created is another order that fails. Neither the escaping murdering brothers nor those who pursued them were more heroic than the other. "I was running with the sword which was a pencil in my hand …the order was to capture the bird draw it bring it back converted into a hero. The horse told me our hero will be two, and with us, three, the great hero, the excluded." This is a dream, however, and the birds and the landscape keep disappearing or becoming each other. Heroism, like language, is not one, is mutable, is really just a matter of survival.

Speaking of survival, how does the political context of the poetry of XUL survive translation? The coded political language of this poetry often appears in the English version as a kind of reserve or obliqueness, almost a paranoia, a sense of hiding something. From The Shock of the Lenders, for example, "some of the neighbors saw the incident: it was inconvenient: they forgot it three times." What the incident is never gets specified; the referent in both original and English version is "disappeared." In the Spanish, it is conspicuous in its absence, just as the neighbors must work hard to maintain the repression, the object of which keeps returning. It is important that what is disappearing may be actual human beings, but without context knowledge this sense may be lost to North American readers, who can nonetheless sense that something is going on, that there is a gap in the poem with much inside it. Perednik encourages English-speaking readers to hone their skills at detecting these gaps, invites them to follow the new paths opened by them, and encourages them to take this activity on as a responsibility.

Significantly, The Shock of the Lenders is a poem of both detection and terror. The 1981 Schoklender murder case, which became a national sensation in Argentina, seemed to shatter any attempt of the middle class to retain complacency and a sense of safety under the dictatorship. The case exposed middle-class efforts to repress or distance the violence and corruption of the Dirty War by showing how the violence and corruption of the middle-class Argentine family intersected those of the Dirty War. The Schoklenders were an upper-middle-class educated family displaying all the outward signs of success: the father, Mauricio, was an engineer; they lived in a fashionable Buenos Aires neighborhood; there were three children. On March 30th, 1981, a neighbor followed a trail of blood to the bodies of Mauricio and his wife Cristina in the trunk of the family car. The two sons, Sergio and Pablo, were missing. A country-wide search began, and in a few days both sons were apprehended on horseback, one having fled to the north, the other to the south. The trial uncovered many skeletons in the family closet, including possible incestuous relations between Cristina and both sons, and the involvement of Mauricio's engineering firm in international arms traffic for the dictatorship. The Shock of the Lenders uses the case to respond to a moment in Argentina when language, the social order, logic, and the family have been broken by the repressive military dictatorship, and asks what can be said, and how, under these conditions.

For a reader in any language, including English-speaking readers, it also asks what can be found out, and how. Readers, especially English-speaking readers, may need to detect what is happening, and what the experience of terror in the poem is for the poet and for themselves. However, the typical tools of detection, logic and reason, will fail here. For one thing, these are ostensibly the tools of the dictatorship as they ferret out and hunt down dissenters, torturing and then disappearing them. They are also the tools of those middle-class educated Argentines who wish to repress what is happening by taking refuge in their own education and in the idea that order still exists. However, in The Shock of the Lenders and the other poems in this volume, Perednik persistently rejects rationality or logic as a usable framework.

"The day is too clear to see what's happening/: a link in the chain has been broke/: crystals colors solstice equinox have been broke/Too clear to see/The fear what's hidden under always." It is not even that he rejects the framework of rationality; through the how that the poem says, he expresses its impossibility. While the poem asserts that "the day is too clear to see what's happening," the unclear and broken persist in being spoken. When terror has settled in someone, or in a society or a language, the gaps and the inability to make sense of things in a conventional way are already there. The always inherent gaps in conventional order and logic are exposed in all their glory because, when one is living in terror, the fiction of their infallibility can no longer be maintained. The English-speaking reader, entering the brokenness of the poem, enters the continual effort to create order, to stabilize the situation, and is, with the poem, unable to do so. In this poem, there is no interpreter in control who is separate from the brokenness of the poem--no detective, no judge, no righteous citizen who is better than the fugitive murdering sons, no middle-class Argentine or North American who is unscathed.

And yet Perednik also has a powerful sense of the ineffable or the unknowable, of what rises up from the gaps or broken pieces. Often what rises in his work is humor. In The Shock of the Lenders, "three crazy elves…lean together and howl to break down the door" of the executive's office, guarded by the secretary (these three crazy elves were Perednik, XUL poet Jorge Lépore, and Ernesto Livon Grosman, giving in gleefully to the absurdity of a "red tape" situation). In 2X2, Livon Grosman's short film of Perednik reading Bernstein and Bernstein reading Perednik, Perednik invests his reading of "Dear Mr. Fanelli" with just this sense of how tragicomic the absurdity we all have to live with is: "Mr./Fanelli, there are/a lot of people sleeping/in the 79th Street station/& it makes me sad/to think they have no home/to go to. Mr./Fanelli, do you think/you could find a more/comfortable place for them/to rest?" (Bernstein, My Way: Speeches and Poems (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999). My Way: Speeches and Poems, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). Perednik emphasizes the line breaks before "Fanelli," pausing before rolling the name off his tongue in Italian-inflected Argentine Spanish as he looks dolefully at the camera. This is funny, but also earnest. Or Perednik is the "Great Skidder" (or kidder) away from order, in the poem of the same name: "I skid/I skid/I skid/kid." Poetry is a way of surviving, for now: in The Shock of the Lenders, "poetry is not truth/not beauty/leaves someone burns against the cold."

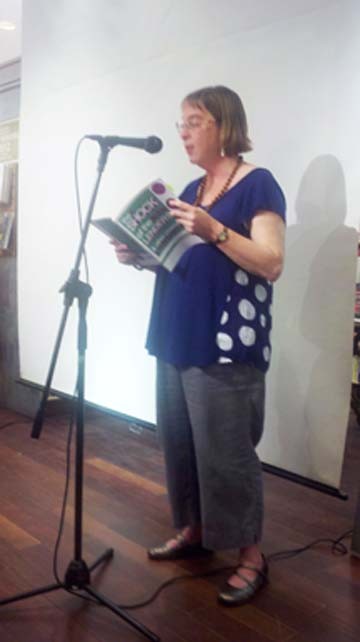

Back in the late 80s, I arranged for Perednik to give a poetry reading at Swarthmore College. When he came back, he played me the tape from the reading, looking at me expectantly with a little smile as the tape wound on in silence. Eventually I cracked and said I didn't understand, and he explained that the publicity notices had listed the wrong date, and no one had shown up. It is characteristic of Perednik that he took this breakdown of communication, this ostensible failure, as an occasion for play--even as an occasion to acknowledge the mystery in the ordinary events that generate "the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to."

In Benjamin's "afterlife," paradoxically an original text changes not due to historical forces or changes in subjective valuation, but rather due to the aliveness of language itself. Willfully perverting Benjamin's "afterlife" to include the historical and the subjective as inseparable from the life of language, I'd like to ask how the English poem has changed since the "Main Fragment" was first published in Sulfur in 1992. It was the height of the era of Language poetry, when it sometimes seemed that L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E was the only framework within which to interpret experimental poetry. Has the poem shifted for English-speaking readers with the more recent opening to a wider range of poetries? How has the poem shifted for English-speaking readers in the wake of 9-11? Perhaps its expression of a futile effort to maintain complacency in the face of terror's reality now strikes closer to home. On a subjective level, I could never have imagined when translating the poem how I would read it after my mother-in-law was murdered many years later, when I came to more fully inhabit the poem. Perednik himself now has lung cancer. He has come closer to the point where all language stops and we enter the realm of the unknowable that rises from among the gaps in his poems. Rereading these poems while preparing the manuscript, during a period when my own mother was dying of cancer, I kept thinking that the poems can prepare any of us for the surrender and relinquishment of unitary self.

Unlike Benjamin, Perednik views translation as writing that is equal to the writing of the original. Perednik himself has translated widely: Olson, Nabokov, cummings, and Rothenberg, among many others. In XUL number 9 (1993), the translation issue, in an essay on translating Nabokov, Perednik writes: "What makes translation interesting is that it relates two distinct pieces of writing and affirms, in some oblique way, that they are identical. Which brings the reader an enrichment or complication in his tasks….The result of translating a piece of literary writing, for whoever likes literature beyond the telegraphic or beyond spiritualism, can be more than a message or the invocation of an absence: it can be another piece of literary writing." Here is another case in which trying to read a fragmentary text for the whole, original text beneath it is beside the point. There is no hierarchical order here. Instead, Perednik focuses on the puzzle of reading texts that are side by side, identical yet distinct.

Perednik is nothing if not a collaborative writer. Presenting the works of others, whether through XUL Magazine or his translations, has always been at the core of his writing enterprise. And by necessity he enters into dialogue with these other poets, admits their influence and contributes his own. He creates a sense of writing as happening in a field that includes other writings that resonate off each other. When I was working on The Shock of the Lenders, I also spent many evenings with Perednik and Ernesto Livon Grosman as they worked on early drafts of translations of Charles Olson poems. We sat around the kitchen table at Perednik's apartment speaking with wonder and exasperation about the irreducibility of certain words or phrases in Olson's English and the obscurity of others.

I learned from translating Perednik to respect the irreducibility of a wrong word in a translation by creating a new irreducibility or wrongness rather than smoothing it out. Thus at the end of the "Main Fragment" "su turbía historía," which adds accents to the normally unaccented "i's" in these words, defamiliarizing what might otherwise be a stock phrase, becomes not "his troubled story" but rather "his cloudied storied." Perednik's sense of wonder at language's peculiarities inhabits his poems and translations and my translations of his poems; the language may be particular, but the wonder at it is shared.

Recently while translating "Poetarzan," which is about this wonder and strangeness of language, I sent an e-mail to Perednik in which I described a challenge I was having with the end of the poem. "todo lo que mí escribir sonar extraño a poetarzan/ajeno y propio como verdad/como verdor": "verdad" (truth) and "verdor" (greenness) created a sense of elemental likeness-making with the similar-sounding words seeming as concrete as objects in the jungle. I complained that I could have gone with "verity" and "verdure" to capture the likeness, but the fussy latinate pair in English would not get the elemental sense of the Spanish pair (in Spanish, whose primary origins are Latin, latinate words sound natural, not high-tone, as they often do in English, a Latin/Anglo-Saxon hybrid). Perednik only replied that he knew I would find a solution; indeed, I'd written not for help, but simply to share with him once again the wonder of the quandary. I ended up skidding to a different angle, less literal: "Everything me write sound strange to poetarzan/foreign and own like life/like leaf." We can now put these versions side by side and wonder at their particularities and their relationship.

As for The Shock of the Lenders, from the beginning it contained a dialogue with English: its Spanish title sends the name "Schoklender" skidding into alien territory by tearing it to pieces that are words in a foreign language: El Shock de los Lender. And the poem begins: "The most beautiful word in the language is stranger/Barbaric or Barbara/All men are mortal the shock lender is also/The most beautiful concept in the mother tongue." Translation seems a natural mode of writing when a language, or a society, differs from itself, contains the alien, or the barbaric, within. The poem was always waiting to meet its English version and to talk to it.

In "FOUR P(R)O(BL)EMS," a prose piece reprinted here from a special Boundary 2 issue on International Poetics (Boundary 2 (26), 1999), Perednik returns to the importance of context for poetry. He points out that while the poem, the author, his life, and his era may all have "relative autonomy," they are contiguous, and thus related. "One is born alone and dies alone, and some or all of us are the context of that one. This is the definition of culture." Thus "the poem has an outside"; perhaps it, or any of us, are fragmentary insofar as we consider ourselves unitary, whole, and self-sufficient without context. Let us then join together to become the context of The Shock of the Lenders and to let it become ours.