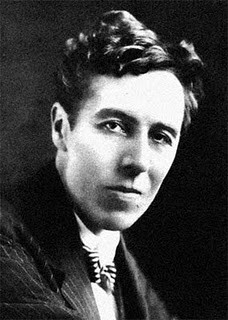

Firbank as poet, by Douglas Messerli

Ronald Firbank *Valmouth* (London: Gerald Duckworth, 1919)

In preparation for a fiction course for the MFA Creative Writing Program at Otis College of Art this Fall, I reread Ronald Firbank's fiction Valmouth, and sought out his biography on Wikipedia, where I read the author "produced a series of novels."

Since I consider myself a sort of authority of the various genres of fiction, I am no longer surprised to see that any fiction is described by most readers these days as a "novel." And, although the genre, "novel," seems to me to center on a central figure, charting his or her relationship (often in symbolic terms) with the larger culture or, at least, the world outside the central figure, I have become somewhat indifferent if people use the term "novel" indeterminately.

The only times it truly upsets me is when readers have difficulty with a work of fiction because it does not meet the standard expectations of a "novel," such as the case of Djuna Barnes' anatomy Nightwood, a work that wasted the energies of at least one critic, Joseph Frank, in creating a new form (what he called "spatial fiction") to explain what he saw as anomalies, all perfectly a home in the anatomy genre. Others have approached the epic fictions of Heimito von Doderer and Robert Musil, works whose structures often work more like musical compositions than plot-organized novels, similarly. But when I raise these issues, I usually get blank stares or significant harrumphing.

I might have described Firbank's Valmouth as a dialogue fiction, a work that uses conversation as its major structural device, a writing that can be traced back to Plato's Dialogues. Indeed I intend to teach this work in a course titled "Dialogue Fictions," which includes works by Elizabeth Bowen, Henry Green, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Anthony Powell, and others.

This time my reading, however, revealed that perhaps I have been wrong in even presuming to describe Valmouth and most other Firbank works as "fictions." While it is true that many kinds of fiction contain little or no plot—and Firbank seems unable to close any event, let alone begin it—at least most fictions have a narrative. If there is one in Valmouth, it can be summarized by saying that the book is primarily about a group of elderly women, women who have survived longer that those in other English communities either because of the Valmouth air or its water. The major "event" of Valmouth consists of a grand dinner party for these women and most of the town's citizens in Hare Hall. Little of importance happens at this occurrence—indeed it is often difficult to know throughout the work what indeed might be "happening"—but it is significantly placed near the center (p. 78 of a 127 pages) of the work.

There also appears to be no "central" character, indeed no "real" characters, Firbank preferring names (Teresa Twisleton, Rebecca Bramblebrook, Flo Flook, Simon Toole, Tircis Tree, Mrs. Hurspierpoint, etc. etc., listed sometimes for entire paragraphs) over characterization, but three quickly drawn figures do predominate, namely the black masseuse, Mrs. Yajnavalkya, her mysterious niece Niri-Esther, and Mrs. Thoroughfare's son, Dick—a sailor who is away from home for most of the fiction. If one must point to a single central figure, it would have to be Yajnavalkya, since it is clear that she is the most intelligent and exuberant figure in the book.

Firbank clearly loved Blacks, and writes about them in several of his "fictions." His admiration for Blacks, however, does not mean that he escapes the prejudices of his time (Valmouth was first published in 1919); the word "nigger" appears once or twice in this book, and in the title of his Prancing Nigger. The elderly women seem to be of two minds concerning Yajnavallkya, as they praise her ointments and the touch of her fingers alternating with disdain for her race.

In fact, we don't ever truly know Yajnvalkya's ethnic background. At times she is simply from "the East," at other times she appears to have traveled from Africa or India, while at the end of the work, it appears, she is Tahitian, her niece born of Tahitian royalty. It hardly matters, since it is apparent that what Firbank most enjoys is the possibility of using his "Black" figure to create another kind of voice, in this case through a sort of strange mélange of dialect and argot. At least she is given a few full sentences ("We Eastern women love the sun...! When de thermometer rise to some two hundred or so, ah dat is de time to lie among de bees and canes.").

The rest of the figures utter half sentences, phrases, overheard remarks. Most of this work is so utterly fragmented that—although we glean that the conversation is usually about societal behavior and love—the meaning and significance of the dialogue is impossible to detect.

Mixed with Latinate sentences, French phrases (some of them poorly put together), and an occasional German word or two, the fragments coming from these figures' mouths is less a dialogue than a series of signs, linguistic clues to what might or might not have happened:

There uprose a jargon of voices:

"Heroin."

"Adorable simplicity."

"What could anyone find to admire in such a shelving profile?"

"We reckon a duck here of two or three and twenty not so old.

And a spring chicken anything to fourteen."

"My husband had no amorous energy whatsoever; which just

suited me, of course."

"I suppose when there's no more room for another crow's-foot,

one attains a sort of peace?"

"I once said to Doctor Fothergill, a clergyman of Oxford and a great

friend of mine, 'Doctor,' I said, 'oh, if only you could see my—'"

"Elle était jolie! Mais jolie!...C'était une si belle brune...!"

"Cruelly lonely."

"Leery...."

"Vulpine."

"Calumny."

"People look like pearls, dear, beneath your wonderful trees."

This goes on for several pages, and such passages dominate the entire text.

At several other moments we overhear the whispered conversations of servants:

"Dash their wigs!" the elder man exclaimed.

"What's the thorn, Mr. ffines?" his colleague, a lad with a face gemmed

lightly over in spots, pertly queried.

"The thorn, George?"

"Tell us."

"I'd sooner go round my beads."

"Mrs. Hurst cut compline, for a change, to-night."

"...She's making a studied toilet, so I hear."

"Gloria! Gloria! Gloria!"

"Dissenter."

"What's wrong with Nit?"

The younger footman flushed.

"Father Mahoney sent me to his room again," he answered.

"What, again?"

"Catch me twice—"

"Veni cum me in erra coelabus!"

"S-s-s-s-s-s-sh."

"Et lingua...semper."

At least we can sense what's behind their gossip, namely the sexual attacks of the priest on the young footman; but just as often these conversations offer up no real information.

Similarly, there are passages of fragmented readings, the one below listened to by Mrs. Hurstpierpoint between the Aves of her beads:

Music, she heard. Those sisters † a ripe and rich marquesa † strong proclivites †

a white starry plant † water † lanterns † little streets † Il Redentore †

Pasqualino † behind the Church of † Giudecca † gondola † Lido † Love †

lagoon † Santa Orsola † the Adriatic——

Again, we get the idea, the satiric mix of the sacred and the mundane, a romantic love story set against the movement of the prayer beads, but there is no other significance, and even that has been revealed to us through signs and symbols.

Niri-Esther speaks throughout in a language of her own, using phrases such as "Chakrawakt—wa?" and "Suwhee?" A passing drunk sings an entire song in a near-nonsense language:

"Lilli burlero, bullen a-la.

Dar we shall have a new deputie,

Lilli burlero, bullen a-la.

Lero lero, lili burlero, lero lero, bullen a-la,

Lero lero, lilli burlero, lero lero, bullen a-la.

Ara! but why does he stay behind?

Lilli burlero, bullen a-la.

Ho! by my shoul 'tis a protestant wind.

Lilli burlero, bullen a-la.

Lero lero, lilli burlero, lero lero, bullen a-la,

Lero lero, lilli burlero, lero lero, bullen a-la

Now, now de heretics all go down,

Lilli burlero, bullen a-la

By Chrish! and Shaint Patrick, de nation's our own—

Similar songs appear in his other works, this little gem from Prancing Nigger:

" I am King Elephant-bag,

Oh de rose-pink Mountains!

Tatou, tatouay, tatou..."

My point in mentioning these numerous fragmented passages (and I might have selected nearly any page in Valmouth for examples) is that it is clear Firbank is not at all interested in telling or even circuitously conveying a story. His pleasure is in language, not in fiction. Even when he has set up a scene, as he does at the end of the book, gathering all the work's figures together for the marriage of Niri-Esther, the Black Tahitian princess, to the fair-haired inheritor of Hare Hall, Dick, nothing comes of it, as Dick suddenly disappears from the scene and book and, while the community impatiently awaits within the church, Niri-Esther, wandering out-doors follows a butterfly. The work ends with no attempt at conclusion or even suggestion of one. Absolutely nothing happens. It is as if Firbank were toying with any reader who might seek an interrelated narrative.

Yet, Firbank's works, for some—for me—are highly enjoyable, delightful forays into linguistic silliness, as somehow both the old and the young of this work come together again and again to talk, to share idle gossip, gripes, complaints, and tales of illicit or imaginary love. Although we never know the full content of any of these, we can—the author requires it of the reader—fill in the blanks, turning Firbank's characters' words into our own desires and disappointments. In short, anyone coming to Firbank expecting a story, a kind of "novel"—no matter how one defines that—will be disappointed. For Firbank is closer to being a poet than a storyteller, a man interested more in the play of language than in what it means.

Douglas Messerli

Los Angeles, July 28, 2011

Originally published at Exploring Fictions, reprinted with the permission of the author.