'we have sold our proper heritage for a pot of message’: A note on Morris Croll

Morris Croll (1872–1947)

I am interested in the way Croll’s account of the anti-Ciceronian or Baroque prose can be related to critiques of the “plain style” of expository prose that took force in his time and remains powerful in some ideologies of “composition.” The contrast of “plain style” or tight/correct expository “sentence” is the “loose” period (aka “libertine” thought of Montaigne and Ralais).

I am interested in the way Croll’s account of the anti-Ciceronian or Baroque prose can be related to critiques of the “plain style” of expository prose that took force in his time and remains powerful in some ideologies of “composition.” The contrast of “plain style” or tight/correct expository “sentence” is the “loose” period (aka “libertine” thought of Montaigne and Ralais).

NB: Francis Christensen (see below) is an advocate, in Comp theory, of the generative or cumulative sentence, e.g “loose” style.

Good summary review of Croll from the point of view of comp/rhetoric by Richard Young:

“Style, Rhetoric, and Rhythm: Essays by Morris W. Croll”: Rhetoric Review Vol. 16, No. 1 (Autumn, 1997) , pp. 158–61 (JSTOR):

Maurice Croll’s essays … were arguably the most important of the early contributions to the history of rhetorical stylistics and remain a standard reference.

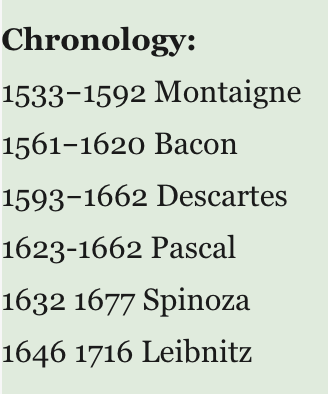

Croll saw the Anti-Ciceronian movement, beginning in the latter part of the sixteenth century and continuing throughout the seventeenth, as a reaction to the elaboration, formality, and aural appeal of the Ciceronian style. The Anti-Ciceronians looked to Seneca, Tacitus, and Thucydides for alternatives to a style they thought of as decadent. But the movement was also a reaction to what the Ciceronian tradition had come to symbolize in politics, religion, science, philosophy, and education. The Anti-Ciceronians represented for Croll the modem spirit emerging in the Renaissance, with its new epistemology, science, and politics.

The Anti-Ciceronians — represented perhaps most notably for us by Donne, Bacon, and Browne in England and by Pascal and Montaigne on the continent — sought a style that was more contemplative than oratorical, more natural and spontaneous, closer to the movements of the inquiring mind. It was a written style rather than spoken, the style of the essayist rather than the orator. Croll argued that

expressiveness rather than formal beauty was the pretension of the new movement, as it is of every movement that calls itself modem. It disdained complacency, suavity, copiousness, emptiness, ease, and in avoiding these qualities sometimes obtained effects of contortion or obscurity, which it was not always willing to regard as faults. It preferred the forms that express the energy and labor of minds seeking the truth, not without dust and heat, to the forms that express a contented sense of the enjoyment and possession of it. In a single word, the motions of souls, not their states of rest, had become the themes of art.

Croll notes that the baroque style of the Anti-Ciceronians tended increasingly toward a semantic complexity that strained the syntactic resources of the language.

… the process of disintegration could not go on forever. A stylistic reform was inevitable, and it must take the direction of a new formalism or “correctness.” The direction that it actually took was determined by the Cartesian philosophy, or at least by the same spirit in which the Cartesian philosophy had its origin. … To this mode of thought we are to trace almost all the features of modern literary education and criticism, or at least what we should have called modern a generation ago: the study of the precise meaning of words; the reference to dictionaries as literary authorities; the study of the sentence as a logical unit alone; the careful circumscription of its limits and the gradual reduction of its length; the disappearance of semicolons and colons; the attempt to reduce grammar to an exact science; the idea that forms of speech are either always correct or incorrect; the complete subjection of the laws of motion and expression in style to the laws of logic and standardization-in short, the triumph, during two centuries, of grammatical over rhetorical ideas.

The passage was quoted by Francis Christensen in one of his articles on what he called the “cumulative sentence,” which was known earlier as the loose period, one of the characteristic forms associated with Anti-Ciceronian style (Notes Toward a New Rhetoric. New York: Harper & Row, 1967 [and see Christensen excerpts below]). Since Christensen believed that modern writers have more in common with those of the seventeenth century than with later writers, particularly the advocates of the Plain Style, it is not surprising that in his proposals for teaching style, he acknowledges Croll’s influence. Reading Croll on the complexities of seventeenth-century stylistics, we understand what Christensen meant when he remarked that “we have sold our proper heritage for a pot of message” (15). We also see what it means to have a rhetorical theory of style, in contrast to a grammatical theory of style or a psychological theory (i.e., style as the expression of the individual personalty).

•••••

Francis Christensen, A Generative Rhetoric of the Sentence College Composition and Communication, Vol. 14, No. 3, Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, 1963: Toward a New Rhetoric (Oct., 1963), pp. 155–61 Published by: National Council of Teachers of English

JSTOR

I want to conclude with a historical note. My thesis in this paragraph is that modern prose like modern poetry has more in common with the seventeenth than with the eighteenth century and that we fail largely because we are operating from an eighteenth century base. The shift from the complex to the cumulative sentence is more profound than it seems. It goes deep in grammar, requiring a shift from the subordinate clause (the staple of our trade) to the cluster (so little understood as to go almost unnoticed in our textbooks). And I have only lately come to see that this shift has historical implications. The cumulative sentence is the modern form of the loose sentence that characterized the anti-Ciceronian movement in the seventeenth century. This movement, according to Morris W. Croll, began with Montaigne and Bacon and continued with such men as Donne, Brown, Taylor, Pascal. Croll calls their prose baroque. To Montaigne, its art was the art of being natural; to Pascal, its eloquence was the eloquence that mocks formal eloquence; to Bacon, it presented knowledge so that it could be examined, not so that it must be accepted. But the Senecan amble was banished from England when “the direct sensuous apprehension of thought” (T. S. Eliot’s words) gave way to Cartesian reason or intellect. The consequences of this shift in sensibility are well summarized by Croll:

To this mode of thought we are to trace almost all the features of modern literary education and criticism, or at least of what we should have called modern a generation ago: the study of the precise meaning of words; the reference to dictionaries as literary authorities; the study of the sentence as a logical unit alone; the careful circumscription of its limits and the gradual reduction of its length; . . . the attempt to reduce grammar to an exact science; the idea that forms of speech are always either correct or incorrect; the complete subjection of the laws of motion and expression in style to the laws of logic and standardization-in short, the triumph, during two centuries, of grammatical over rhetorical ideas.

Here is a seven-point scale any teacher of composition can use to take stock. He can find whether he is based in the eighteenth century or in the twentieth and whether he is consistent — completely either an ancient or a modern — or is just a crazy mixed-up kid.