Charles Reznikoff's "Amelia": A case study by Richard Hyland

Richard Hyland, Distinguished Professor, Rutgers Law School, Camden, New Jersey, has compiled the fullest account of the sources of a Charles Reznikoff poem, together with a detailed commentary on the Amelia Kirwan case and the poem Reznikoff wrote based on this case. Many of Reznikoff's poems, especially those in Testimony, are based on legal records. But there has been little research on the exact relationship between the legal record and the poem, with the general assumption that Reznikoff used only language from the legal records, cutting away but not adding any of his own words. The key to Reznikoff's aesthetic is his selection and condensation of the source materials.

Surely Reznikoff is a paradigmatic poet for all documentary and source-based poetry of the 20th century and exemplary for many of us who use appropriated or found material in our work. By looking at the 1910 court records, we can now see the source of the language that Reznikoff incorporated into his poem, at least in this one instance. Hyland goes much further. By contrasting the aesthetic pitch of Reznikoff's slim poem with the social efficacy of Judge Edward Bartlett's magisterial decision, Hyland gets to the core issue of the office of poetry. Reznikoff's poem, he notes, perhaps wryly, is "weak."

Poetry is a weak thing. And that is its strength.

•

I read the poem and provided a commentary on it for the Library of Congress's "Poetry of American Identity" feature in 2013.

•

Three related earlier works that touch on Reznikoff's use of legal source material are Katherine Shevelow’s “History and Objectification in Charles Reznikoff’s Documentary Poems, Testimony and Holocuast” in Sagegtrieb 1.2 (1982), Tom Lavazzi's “Poetic Discourse v. Legal Discourse: The Case of Charles Reznikoff” in the Sagetrieb Reznikoff issue (13.1-2, 1992) and "Traumatic Survival and the Loss of a Child: Reznikoff’s Holocaust Revisited” in Paideuma 36;1-2 (2010). See also Stephen Fredman's A Menorah for Athena:Charles Reznikoff and the Jewish Dilemmas of Objectivist Poetry.

— Ch.B.

Amelia

mp3 audio

Amelia was just fourteen and out of the orphan asylum; at her first job—

in the bindery, and yes sir, yes ma’am, oh, so anxious to please.

She stood at the table, her blonde hair hanging about her shoulders,

“knocking up” for Mary and Sadie, the stitchers

(“knocking up” is counting books and stacking them in piles to be taken away).

There were twenty wire-stitching machines on the floor, worked by a

shaft that ran under the table;

as each stitcher put her work through the machine,

she threw it on the table. The books were piling up fast

and some slid to the floor

(the forelady had said, Keep the work off the floor!);

and Amelia stooped to pick up the books—

three or four had fallen under the table

between the boards nailed against the legs.

She felt her hair caught gently;

put her hand up and felt the shaft going round and round

and her hair caught on it, wound and winding around it,

until the scalp was jerked from her head,

and the blood was coming down all over her face and waist.

[from The Poems of Charles Reznikoff, 1918–1975, edited by Seamus Cooney. Black Sparrow Press © 2005 the Estate of Charles Reznikoff]

Amelia Speaks!: legal source material for Charles Reznikoff's "Amelia"

1910 Court of Appeals case file (pdf; Amelia Kirwan's testimony starts on p. 14)

[from Google Books document of Court of Appeals records]

•

Judge Edward Bartlett's decision

Reznikoff EPC author page

Reznikoff PennSound page

Reznikoff Poetry Foundation page

For Amelia

Richard Hyland

The scene haunts me. I now do not think I will be able to forget it. And I want to know what happened to her. I have searched the web, as creatively as I am able, for some trace of her, but largely in vain. Did she find happiness? Did she meet someone who could love her, someone not bothered by the scars? Did she marry, did she have children? I would like for this story to have a happy ending. I know life is not fair, but if I am not to accept that life has no meaning, this little tragedy has to be redeemed. I have answers to none of these questions. Though I can speculate about why Reznikoff tells us she was blonde.

The parties

Amelia Kirwan was born, probably in New York City, on March 27, 1892. From her surname, it seems that the family had immigrated from Ireland. We know of two of her older siblings—John, who was appointed her guardian a month after the accident for purposes of the lawsuit, and Margaret Weinert, who had begun working at the American Lithographic Co. two years earlier, in 1904, doing the same work Amelia was doing. At the end of her first year with the firm, Margaret was asked to work the wire stitching machines. During the fateful minutes, Margaret was working at a stitching machine across the large room on the fifth floor. Margaret was married a year or so after the accident and, on that occasion, quit her job at the factory.

Joseph Palmer Knapp (1864–1951), the American publisher and philanthropist, founded American Litho in February 1892. Knapp’s father was past president of Metropolitan Life and his mother was a hymn writer. Knapp was particularly interested in game bird conservation. Together with J. P. Morgan he established a foundation that today is known as Ducks Unlimited. To form American Litho, Knapp bought out eight other lithographic companies, many of the leading lithographers of the day. American Litho was likely the country’s first conglomerate printing firm. The company’s name is still visible above the entrance portico at 52 E. 19th St., at the corner of Park (then Fourth) Ave. in Manhattan.

Knapp teamed up with James Duke (1856–1925), head of American Tobacco, to print cigar labels, as well as tobacco or cigarette cards (trading cards offered as a premium with the sale of cigarettes). Duke introduced modern cigarette manufacture and marketing and created an endowment that helped to fund the university that was renamed after his father. Duke, his father, and his brother are interred in the Memorial Chapel on the Duke University campus. American Litho also printed illustrated Christmas cards and, a few years later, World War I recruitment posters. Not long after its founding, American Litho had become the largest printing company in the world.

Before Amelia started work at American Litho, she was an inmate, as they called the children, at St. Joseph’s Female Orphan Asylum, which was located near the corner of Lewis and Willoughby Avenues in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. There is no mention in the legal materials of her parents or of how long she had lived in the orphanage. Her position at American Litho was her first job. She had been hired by the forelady, Miss Blondell, ten days earlier to work in the bindery. The work was on the fifth floor, on the 18th St. side of the building. During her first three or four days at the plant, her duties involved tying up stacks of “Uncle Sam’s” booklets. Then she moved on to knocking up Arbuckle books. Knocking up meant counting the booklets in groups of 25 and stacking them against the wall. The stacks were then removed by another employee.

The Arbuckle books Amelia was working on may have been something like the atlases the Arbuckle borthers published some years earlier.[1] John Arbuckle (1839–1912) and his younger brother Charles became millionaires in the 1890s by introducing the mass production of coffee in sealed individual packages. John was born in Scotland and grew up as the son of a well-to-do cotton mill proprietor in western Pennsylvania. In 1865, the brothers patented a process to seal the porous surface of roasted coffee beans by coating them with a gelatinous mixture of egg whites and sugar. The process preserved aroma while yielding a smooth and pleasantly sweet taste. Their most popular brand, “Ariosa,” was sold to a national market in patented, airtight, one-pound packages. The coffee was particularly beloved by chuck wagon cooks in the Old West. Each package of coffee contained a stick of peppermint candy. The packages were hand filled by about fifty women until John Arbuckle invented a machine to replace them. The Arbuckle factories on Jay Street and their warehouses on Water Street dominated the Brooklyn waterfront. By 1891, the company was the leader in the American coffee market. The Arbuckle Brothers’ entrepreneurial empire eventually included branches in Kansas City, Chicago, Brazil, and Mexico, as well as the ownership of sugar plantations and a fleet of seagoing vessels. The Arbuckles required large quantities of sugar to coat their beans and produce the candy stick. To acquire sugar at competitive prices, John Arbuckle spent years breaking the sugar trust dominated by Henry O. Havemeyer’s American Sugar Refining Company.

The Arbuckles advertised aggressively issuing folksy colored handbills and a great variety of trading cards, which included images of birds, animals, cooked dishes, satirical scenes, sports, and maps. The maps, which included vignette illustrations of local industries and scenery, were especially popular. In 1889, Arbuckle Brothers reissued both the maps of the American states and those of foreign countries in album format, four cards to a page. These two unusual atlases, Arbuckles’ Illustrated Atlas of Fifty Principal Nations of the World and Arbuckles’ Illustrated Atlas of the United States of America, were designed to advertise Arbuckle’s coffee and were available from the company as a mail-order premium. To give some idea, the rear wrapper of the world atlas showed a map of Brazil together with a view of the Arbuckle factory and two finely dressed women enjoying their coffee.

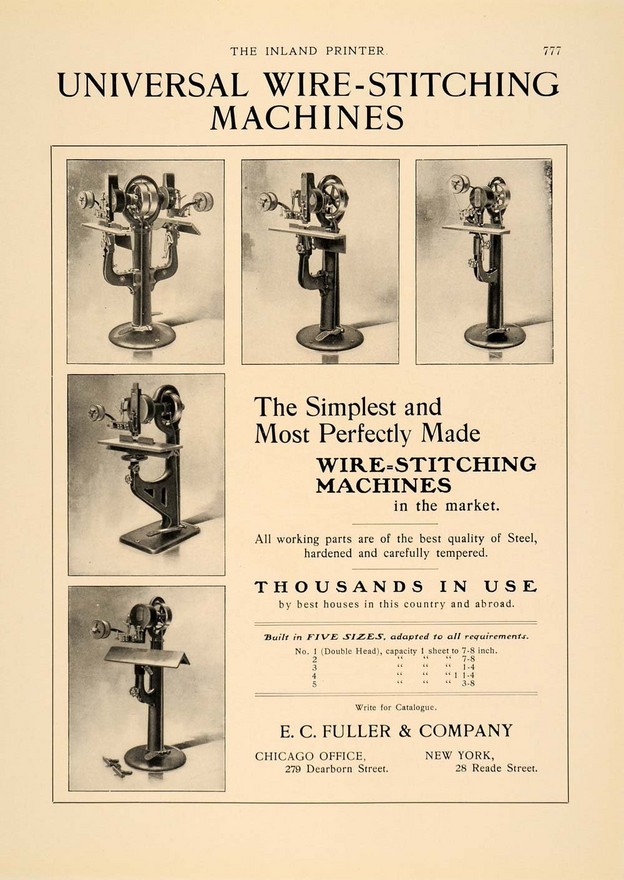

The work

Amelia began to work for American Litho on Monday, June 4, 1906. During her first week, her work kept her away from dangerous proximity to machinery. About four days before the accident, Amelia was assigned to assist two young women known as stitchers, Mary Lauer and Sadie Hernan, who ran machines fastened to tables in close proximity to each other. The machine they worked on was known as the Universal Wire Stitching Machine, No. 5. It used wire thread to bind or stitch the spine of folded book leaves into a booklet or pamphlet. The machines Mary and Sadie used stood about four feet four inches high and were driven by a belt that connected the drive pulley at the top of the machines with a revolving shaft that ran under the tables on which the machines were mounted. The revolving shaft was suspended on standards four inches from the underside of the table and about 18 to 20 inches above the floor. The rotating shaft itself was about an inch and three-quarters in diameter. The shaft turned free, unprotected by any case or box. There were about 25 to 30 stitching machines on the fifth floor. The majority of the machines, those located on the opposite wall, received power from overhead shafting. Only the five machines near where Amelia worked were powered from below.

There were two parts to Amelia’s job. She picked up unbound booklets elsewhere on the floor from the girls who folded them and then she placed them on a table located to the right of the stitchers. As the stitchers stitched the booklets, they threw them on a table to their left that was about 26 inches high. That was where Amelia worked. At the time of the accident, Amelia stood about four feet eleven inches tall. She counted the booklets and stacked them on an adjoining table. When the stack reached 25 booklets, Amelia pushed the stack back against the wall, where it remained until it was retrieved by another worker.

As Amelia’s supervisor, Miss Blondell, passed her one day, she told Amelia to pick the work off the floor. Amelia did as she was instructed. Factory rules required that all good work be kept off the floor. Good work meant work that had been stitched and was still clean. Work that had been soiled remained on the floor and was swept up by the cleaning crew in the evening.

For this work, Amelia earned $4 per week. The wages were paid to Amelia’s sister. Margaret testified at trial that she had received no instructions to pay the money over to her sister. Instead, it seems Margaret saved it for her.

The accident

On Tuesday, June 19, the day of the accident, Amelia arrived at work at 8 am. The accident occurred between 11 and 11:30. She was knocking up Arbuckle books and had managed to stack the finished work into a stack about one foot high. The Arbuckle books had the peculiarity that their covers were smooth and the booklets tended to slip. On that morning, two or three of them slipped off the table and fell through a gap between the tables where the power belt ran. The booklets came to rest near one of the table legs.

The legs of the tables on which machines were mounted were made of wood. In order to provide stability, two boards had been nailed across the legs, one just under the table top, the other at the bottom about two to three inches from the floor. The top board was about four inches wide, the lower board about six inches. The distance between the two boards was estimated differently, but seems to have been about 14 inches.

Amelia stooped down and looked under the table to locate the booklets. She had long hair and kept it pinned up in what she described as a pompadour. As she raised her head under the table, her hair came in contact with the revolving shaft and was immediately wound around it. As her scalp was torn from her head, blood poured over her face and waist. She put her hand up and felt the iron shaft that was continuing to spin. She had never seen the shaft before. It was not visible from her workplace and no one had ever mentioned it to her.

The injuries

John Bell, the foreman of the magazine bindery, came to her rescue. He shut off the power, pulled the tables apart, dragged Amelia out, and laid her on a table. Her torso had been pulled through the boards and had come to rest under the table. Cold towels were placed on her head, then she was transferred to an ambulance, where she was treated for shock and hemorrhage as she was rushed to Bellevue Hospital. She remained at the hospital for nine months.

At Bellevue, Amelia was under the care of Dr. J. Corwin Mabey (1873–1950). Dr. Mabey was from Montclair, New Jersey, and attended the Columbia Medical College. At the time of Amelia’s accident, he was serving on the surgical staff at Bellevue. Dr. Mabey later became a diabetes specialist and returned to practice in Montclair. There he was a member of the Orange (N.J.) Camera Club. His name is mentioned in two undated entries in The New York Times. Under the heading “Montclair Social Doings; Society Waking Up After Its Long Summer of Rest,” a social column announced that Mabey had gone to the Adirondacks. According to the second entry, Dr. Mabey supervised the summer distribution of pasteurized milk to infants who had been born in tenements in New York. All of his children survived the summer except for one who had been taken away and fed on plain milk for three weeks.

At trial, Dr. Mabey testified that, as a result of the accident, more than two-thirds of Amelia’s scalp had been torn away. The scalp had evidently been disentangled from the shaft and transported in the ambulance to the hospital. Dr. Mabey cut the hair from the scalp and sewed it back onto her head. After several days, parts of the scalp began to slough off and were removed as they became necrotic. In July, during the first of two skin grafting operations, skin was taken from Amelia’s thighs and grafted onto the front half of her scalp. Only about half of the graft healed in place. In a second operation a month later, Dr. Mabey replaced skin on the rear of the scalp and also replaced skin that had sloughed off from the front. At the time of the second trial, Dr. Mabey stated that the wound had healed. Nonetheless, he predicted that Amelia would remain almost entirely bald and that there was a strong possibility that some of the grafted skin would eventually crack and slough off.

Amelia left the hospital in March 1907. She recuperated for three months at the Convalescent Home in New Jersey, then she returned to live with her brother. She continued to have her head dressed almost daily at the Bellevue Clinic until January 1908. At the time of the second trial, she had no hair on her head.

The complaint

Amelia’s brother John, who had been appointed her guardian for the purposes of bringing the law suit, hired Henry W. Herbert as his lawyer. Herbert later became presiding judge of the Court of Special Sessions, formally an inferior criminal court in New York City. On October 1, 1906, Herbert filed a complaint on Amelia’s behalf in the Supreme Court of the State of New York for the County of New York. The complaint requested that American Litho pay damages in the amount of $25,000—the equivalent in today’s dollars of about $625,000.

Because the legal proceedings were somewhat complex, familiarity with the structure of the court system in the state of New York is useful. For private law disputes—those involving claims made between individuals and companies, such as for breach of contract or negligence—the United States has two parallel court systems, one run by the federal government, the other by the individual states. Amelia’s suit was brought in the New York state courts. To simplify somewhat, most American court systems have in essence three levels of jurisdiction. The first is a trial court of general jurisdiction. Then there are two levels of appellate courts—an intermediate appellate court and a high court. In many states, the trial court is called the superior court, the intermediate appellate court is called the court of appeals, and the high court is called the supreme court. The nomenclature is different in New York. There the trial court is called the Supreme Court, the intermediate appellate court is called the Supreme Court, Appellate Division, and the high court—in New York it is one of the world’s great commercial courts—is called the New York Court of Appeals. Again, contrary to usage elsewhere, judges on the Supreme Court are called justices while those on the Court of Appeals are knows as judges.

The three levels differ in their competence. The facts are established, often by jury trial, only at trial before the trial court. Once the facts are established, they may not be retried or revised in the appellate proceedings. Though all three courts decide legal questions, that is the only task assigned to the appellate courts. As a result, American law students learn to distinguish between questions of law (Is the defendent's conduct governred by principles of strict liability or negligence?) and questions of fact (What color was the stoplight when the defendent entered the intersection? Did the defendent act as a reasonable person would have acted?). However, this distinction, which is critical for many purposes, evaporates for other purposes, such as when it comes time for an appellate court actually to resolve a dispute. At that moment, as confusing as it may seem, the appellate courts decide the legal questions as uch by reference to the facts and circumstances of the case as to legal precedent. How this works will become clearer presently.

The complaint filed on Amelia’s behalf made two claims.

First, Amelia claimed that American Litho had violated a provision of New York labor law, namely section 81 of Consolidated Laws, chap. 31, which provided that “All vats, pans, saws, planers, cogs, gearing, belting, shafting, set screws and machinery, of every description shall be properly guarded.”[2] Amelia argued that the shafting running under the tables was not properly guarded.

Her second claim sounded in tort, namely that the employer had negligently failed to warn Amelia of the dangers created by the unguarded revolving shaft.[3] As the New York Court of Appeals had explained a few years earlier:

Certain work is inherently dangerous, and yet the master has the right to hire servants to do it. In such cases, however, unless the danger is obvious to an ordinary observer, it is his duty to give them due warning, so that they may refuse to work if they do not wish to run the risk, and proper instructions, so that, if they enter upon the work, they may be able to take care of themselves.[4]

The first trial

The first trial probably concluded on February 20, 1907, since, on the following day, a story about the verdict ran on page 20 of the Evening Telegram under the headline “Girl Gets $5,000 for Lost Scalp.”

Philip Henry Dugro (1855-1920) presided at the trial. Justice Dugro had graduated both from Columbia College and from what was then known as Columbia’s law department. He had been a member of the State assembly, then was elected as a Democrat to Congress, where he served for one term, from 1881 to 1883, but did not run again. He became a judge in 1887 and served as a Supreme Court justice until his death.

At the time of the trial, Amelia was still in the hospital. The case had been put on the preferred calendar because it seems there was some risk she might die. She was carried in and out of the courtroom on a stretcher. I have not been able to locate the transcript for the first trial. However, the testimony seems to have been similar to that offered in the second trial, from which the transcript survives.[5] The jury awarded Amelia $ 5,000, the equivalent today of about $125,000.

The first appeal

American Litho appealed to the intermediate appellate court, the Supreme Court, Appellate Division. We do not have the briefs from this first appeal, but the arguments for the defense can be gleaned from its later brief before the Court of Appeals.[6] American Litho took the position that Amelia had acted unreasonably and was therefore herself to blame for her injuries. Amelia’s duties required her simply to bring printed pamphlets to the stitching table and, after they were stitched, to count and stack them. On the day of the accident, she acted entirely on her own and without supervisory instruction when she attempted to retrieve the fallen booklets. No one had suggested to her that she should crawl through the narrow opening between the slats and attempt to reach across to the far corner of the table.

On this basis, American Litho was able to respond to Amelia’s two claims. First, there is no reason to believe that the rotating shaft was not properly guarded. No one could come in contact with it except by crawling under the table, and American Litho had no reason to anticipate that any of its employees would “attempt to perform any such acrobatic feat.” For the same reason, American Litho had no reason to warn employees that the shaft was there and might present a danger to those reaching under the table.

The company’s lawyers, Frank V. Johnson and Abraham Benedict, cited cases holding that the labor law did not make the employer an insurer for the safety of its employees. The employer had no duty to protect against extraordinary accidents. Rather the employer was required only to provide sufficient protection against those accidents that were reasonably to be anticipated. In particular, the courts had previously held that the statute did not require employers to shield every piece of machinery in a large factory. Instead, protection was required only on those parts of the machinery that were dangerous to employees who were required to work in their immediate vicinity.

Moreover, American Litho argued that Amelia was sufficiently mature to appreciate the danger involved in approaching too closely to moving machinery. Since American Litho could not have anticipated that Amelia would try to crawl under the table, there was no reason for the employer to warn her of the danger of doing so.

The reader of these arguments will immediately understand that this case was litigated before New York enacted a compulsory worker’s compensation law, as it did in 1914, which provided no-fault compensation for all industrial accidents. There are hundreds of cases in the reporters like Amelia’s, in which workers, particularly children, were maimed and incapacitated for life. The novel The Jungle, in which Upton Sinclair chronicled industrial accidents in the meatpacking industry in Chicago, was published just a few months before Amelia’s accident.

On February 7, 1908, the Appellate Division reversed the trial court’s judgment in favor of Amelia and ordered a new trial.[7] The court relied on the principle that masters—at the time, the law called employers masters and called their employees servants—were not required to guard against every possible harm that might befall their employees. Employers were required to protect against only those dangers that a reasonably prudent man—today reasonableness standards are phrased in terms of the reasonable person—would anticipate. In Amelia’s case, the revolving shaft posed no danger to those working at the tables. Moreover, it would be impossible to guard all factory machinery in such a way that no one could find a way to evade the protection. Nor was American Litho required to warn Amelia of the danger. No one could have expected that she would, or could, crawl under the table. The court held that, since the jury verdict was against the weight of the evidence, the judgment must be reversed.

The panel of the Appellate Division that heard the case consisted of five justices. The vote was three for reversal and two for affirmance. Justice Edward Patterson (1839–1910), at the time the presiding justice, wrote the dissenting opinion. Justice Patterson was appointed to the Appellate Division in 1896 after having served on the Supreme Court. When he died, The New York Times wrote of him that “he had high and unusual qualities . . . with an unquenchable and uncompromising desire for truth and justice.” In his dissent, Justice Patterson reminded his colleagues that questions of reasonableness are by nature questions of fact that should be left to the jury. In Amelia’s case, since the table at which she was working did not have a raised edge to prevent the booklets from sliding off, the jury might well have found that it was likely that workers would have to look under the table to recover booklets that had slipped to the floor. Moreover, since the four-inch board nailed just under the table top served to conceal the rotating shaft rather than to protect workers from it, the shaft posed a danger about which employees should have been warned.

The second trial

The case was tried again from November 24 to 25, 1908.[8] By this time, Amelia was living with her brother at 504 First Ave. (I assume that the rooms were on the First Ave. located in Manhattan rather than the one in Brooklyn.) The case was tried before the Justice Joseph E. Newburger. Justice Newburger was 55 years old at the time. He had been appointed to the Supreme Court the year before and would remain a trial judge until 1920.

As a result of the holding by the Appellate Division, Amelia’s lawyer coached her to correct her testimony. At the first trial, Amelia seems to have testified that, in order to retrieve the fallen booklets, she had gotten down on her hands and knees and crawled between the two boards under the table. On that basis, American Litho argued that she had assumed the risk of any injury, since she had not been instructed to do as she did. On the basis of Amelia’s testimony, the Appellate Division held that American Litho had not breached its duty, since it could not have expected that an employee would try to crawl between those two slats. At the second trial, Amelia stated clearly that she had misspoken in the earlier proceeding. What actually happened is that she never had the chance to reach for the booklets since, as soon as she put her head underneath the table, her hair touched the iron shaft.

Amelia maintained her composure on the stand. Even in the face of hostile cross-examination, her explanation of the complex events that transpired at the moment of the accident was clear and understandable. Anyone who has had practice reading trial transcripts knows that, when testimony is recorded word for word and transcribed, it often makes the witnesses seem less intelligent than they are. In Amelia’s case, though the court reporter may have revised Amelia’s words to eliminate breaks and repetitions, Amelia, who just a month earlier was still under medical care, comes across as articulate, intelligent, and sincere. She would not turn 16 for another month.

In this second trial, Amelia’s case did not reach the jury. After Amelia’s lawyer had presented her case, the lawyer for the defense moved to dismiss the case. He argued that nothing in the testimony suggested that American Litho had violated its obligations under the labor law as construed by the Appellate Division. The trial judge found that the testimony did not vary significantly from that offered during the first trial, and that, as a matter of law, American Litho had not breached any obligation. Amelia’s case was dismissed and she was required to pay the employer’s costs of suit in the amount of $343.68.

The second appeal

This time it was Amelia who appealed. It seems the same panel heard the case on the second appeal. I have not found the briefs on appeal. On May 7, 1909, the Appellate Division affirmed its earlier decision per curiam without issuing an opinion.[9] The two dissenting justices reaffirmed their opposition to the order.

The Court of Appeals

Amelia’s lawyers then appealed to the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in the New York judicial system. The record on appeal, including the trial transcript from the second trial and the briefs before the Court of Appeal, are preserved.[10]

On February 8, 1910, the Court of Appeals reversed the decision of the Appellate Division and remanded the case to the trial court for yet another trial. [11] All seven of the court's judges heard the case. Five of them voted in favor of Amelia, one judge dissented without opinion and the last was listed as not voting.

The decision was written by Judge Edward Bartlett (1841–1910).[12] Bartlett, a descendant from a well-known New England family, was the great grandson of two signers of the Declaration of Independence. The Judge graduated from Union College and then apprenticed to study law. He joined the Republican Club and took an active role in purging the judiciary of the influence of the Tweed regime, which led to the impeachment of two judges. Judge Bartlett was also a member of the Albany Club, the Sons of the American Revolution, and the New England Society. While in New York City, he lived at the Union League Club. Judge Bartlett never married. He died a few months after the opinion in Amelia’s case was published.

A typical American judicial opinion opens with a recitation of the procedural history of the case and a description of the current status of the proceedings. The recitation is largely in the passive voice and is meant to be, and usually is, reassuring—things are taking their course and proper deliberation has been devoted to the matter. Given the relative complexity of the proceedings in Amelia’s case, that would seem to be the obvious path for Judge Bartlett to begin his opinion.

Sometimes, not rarely, particularly when the author of the opinion believes that a running start is needed, the opinion begins with a statement of the facts that occurred in the real world before the matter reached the judicial system. In the hands of great jurists, these statements make clear the factors that, in the mind of the judges, determine the result. Both appellate decisions in this case began in this way. It is useful, for this reason, to compare the opening sentences of these two opinions, the majority opinion for the Appellate Division in the first appeal and Judge Bartlett’s opinion for the Court of Appeals.

The Appellate Division, it will be remembered, reversed the judgment in the first trial that had awarded damages to Amelia. Justice Houghton, for the court, began as follows: “The plaintiff was in the employ of the defendant, and at the time of the accident her duties were to bring printed pamphlets to the stitching table and put them in regular piles after they were stitched.” To anyone who knows the facts of the case and the law that governs it, there is no need to read further. Amelia will lose. Her duties were circumscribed. Her attempt to crawl through the slats was her own frolic. If she suffered any injury, that was her own affair.

Judge Bartlett began differently. “The plaintiff was 14 years and 3 months old at the time she entered the service of the defendant company, a large bookbinding establishment in the city of New York.” Once again, the result is immediately clear. There is no need to flip to the end of the opinion to read the disposition of the case. One of the largest bookbinders in the country had taken a young girl into its employ. The company was obviously required to do what was necessary to assure that she would not be injured, especially not grievously so, in the course of her employment. That disequilibrium, what today might be called the inequality of bargaining power, was, for Judge Bartlett, the decisive fact in the case.

It should be noted that, purely on the law, each side brought very good arguments to the table. Due to the fact that industrial accidents in New York City were tragically frequent at the time—the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire would occur just over a year later—there was a remarkable amount of precedent on the questions raised by Amelia’s case. The precise question before the Court of Appeals was whether, on the basis of the facts presented at trial, it was clear as a matter of law that American Litho had acted as a reasonably prudent employer when it failed to provide a cage or box for the rotating shaft and failed to warn Amelia of the danger involved. For a question to be clear as a matter of law, there can be no evidence that raises a realistic dispute about the question. Otherwise, it is a question of fact that should be left to the jury.

There was plenty of precedent in favor of the defense. The Court of Appeals had long held that only those pieces of machinery need be covered, and only those warnings need be issued, which related to dangers involved in the usual operation of the machines and to those workers operating them. The rotating shaft under the stitching machines created no danger to those working at the tables. On the other hand, the job involved keeping the work off the floor. The Arbuckle booklets were prone to slip and there was nothing on the tables to prevent the booklets from falling to the floor. The stitchers threw the work onto the tables as they finished stitching them. It was obvious that some would eventually slip, and that girls like Amelia would have to crawl around to find them. Moreover, the girls in those positions were not just underage, they were still children. And then there is for me the decisive factor, and that is that Amelia was injured as she was going out of her way to follow instructions, doing everything she could to perform at a high level. To refuse her compensation because she was particularly meticulous in the performance of her duties seems cruel.

After reciting the facts of the case at considerable length, Judge Bartlett announced the rule to be derived from the situation:

If the master hires young children, especially girls with long hair, to work near revolving shafting, it is his duty to guard it, and in so doing to take into consideration their age, inexperience, and lack of care and discretion, and adopt a shield or device that will prevent the liability of their heads coming into contact with dangerous machinery while engaged in the performance of the work assigned them.

In response to the holding of the Appellate Division that American Litho had no reason to anticipate that Amelia would have to reach under the table for any purpose, Judge Bartlett wrote that the reason was clearly supplied during the second trial, namely the factory rule that good work was to be picked up from off the floor. Judge Bartlett held that this new testimony raised a question of fact that should be decided by a jury. The Court of Appeals therefore remanded the case to the trial court for yet another trial.

Further proceedings

I have been unable to locate any further proceedings in the case. I would guess that the case settled quickly after the lawyers learned of the decision by the Court of Appeals. Though there is no evidence, I would think they agreed to the $5,000 awarded in the first trial. Amelia’s lawyers may not have wished to roll the dice before yet a third jury, while American Litho may have been reluctant to risk a possible judgment for five times that amount. Settlements are usually confidential and are not entered in the public record.

Reznikoff

Reznikoff

No one would today remember Amelia if it were not for Charles Reznikoff’s free verse retelling of her tale. It is interesting to speculate about how he first became acquainted with her case.

Reznikoff started law school at NYU in 1912, two years after the decision by the Court of Appeals. He graduated second in his class in 1915 with an LL.B. and then for a year took post-graduate courses at Columbia Law School. He became a member of the bar in 1916 at the age of 22 and then practiced law briefly.[13]

The case lost virtually all legal interest after the New York state legislature passed workers’ compensation legislation in 1914. Before that date, however, it represented an important case in negligence law, particularly on the question of how to distinguish between questions of law and questions of fact. Negligence is a field of tort law, and every American law student takes Torts during the first year of law school. When Reznikoff entered law school, Torts was usually a two-semester course, with a significant focus on the cause of action for negligence. In those days, professors still read the advance sheets, the reports of recently decided cases. My best guess is that Reznikoff’s Torts professor had read the case and mentioned it in class, perhaps even recommended to the students that they consult it in the library. A recent decision of the Court of Appeals on a topic relevant to class would not have gone unmentioned in New York law schools at the time.

Another interesting question is how Reznikoff became acquainted with the facts of the case that are not found in the two published opinions. His poem follows the order of exposition adopted by Judge Bartlett, but it mentions information that Bartlett did not include. For example, the two stitchers with whom Amelia worked are named in the poem but not in the opinion. The opinion also does not mention the number of stitching machines on the floor—there were between 25 and 30, but Reznikoff reduced that number to twenty. Bartlett mentioned that one or more pamphlets had fallen on the floor. Reznikoff raised the number to three or four, a detail he found in Amelia's testimony. Amelia testified that it was two or three. Most importantly, Judge Bartlett refrained from describing the moment of the injury, the way Amelia’s scalp was torn from her head as her hair touched the spinning shaft. The final five lines of the poem recreate the accident by supplementing the description Amelia provided at trial. Amelia's description of the events was available only in the court record. Perhaps the volumes containing the record of cases before the Court of Appeal were also available in the law libraries at either NYU or Columbia, though I have been unable to verify this. They were perhaps available at other legal libraries in New York City.

Finally, there are two words in the poem for which there is no source in the legal materials.

The first is perhaps the central word in the poem, namely gently, which appears at the end of line 17. As far as I can tell, nowhere in the record does anyone use that word, either to describe how Amelia’s hair was caught on the shaft or for any other purpose. That word is Reznikoff’s and the poem turns on it. Just as Amelia is imperceptibly snagged on the shaft, so the reader is snagged on the poem. Once we get to that point, the poem pulls us into the experience and there is no longer a way out. We experience some of Amelia’s terror, as much as a poem is capable of conveying of such an emotion.

The color of her hair

Second, Reznikoff tells us that Amelia’s hair was blonde. I have found that detail nowhere in the materials. Amelia was probably of Irish descent, so it is indeed possible that she was blonde. Perhaps Amelia’s hair color was suggested by the fact that her supervisor was named Blondell, a name that appears even in Judge Bartlett’s opinion. Perhaps Reznikoff was thinking of traditional associations with blond-haired girls, especially in the context of an innocent young creature who confronts a mighty villain. Another possibility, one I do not reject but that seems strange, is that Reznikoff might have located Amelia and encountered her in person.

It is more likely that Reznikoff understood that he was pursuing a task complimentary to, but very different from, the task of the judges and the legal system. To explore this question, it becomes useful to examine briefly the vision that lies at the root of Judge Bartlett’s opinion.

The foundation of production

Judge Bartlett’s opinion is a fine piece of legal writing. Apart from his deftness at displacing the focus from that offered by the Appellate Division to the very different one necessary for Amelia to win, Judge Bartlett also presented a vision of American society at the time and particularly of the industrial production process from those years. American Litho was a corporate giant providing printing and binding services to other corporate giants. The critical work in those factories was performed by a group of very young women, some of them no more than children, including a brave and perceptive girl by the name of Amelia who had only recently emerged from an orphanage. The opinion was written in the context of the debates provoked by the first wave of feminism, though still a decade before the triumph of the movement in the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

Already at this time, Judge Bartlett seemed to recognize that, incongruously, these mighty corporations were being built by the work of young girls at pivotal positions in the production process. Since these young women were of such critical importance to American society, society had not just a moral interest but also a very practical one in taking good care of them. And, as the case demonstrates, a fabulous array of talent was devoted to just this task. Amelia’s doctor was well qualified and devoted to her healing. Insightful and compassionate judges at all three judicial levels took the time to consider her case carefully and decide in her favor. Amelia and her fellow employees responded by making their best effort for their employers. They strove to satisfy all of the demands that were placed on them.

The only thing wrong in this picture, glaringly and monstrously wrong, is the total lack of concern that the corporations themselves showed for these young persons. Those corporations not only failed to protect their workers, their most important resource, even the youngest of them, these corporations fought legal battles to prevent those of their workers who were injured while in their employ from recovering compensation. The message Judge Bartlett conveyed, and it is not far below the surface, is that the profit motive contraadicted the society it was itself creating.

In this context, there is something sublime about the operation of the law, the way Judge Bartlett crafted an opinion that is not only persuasive, but, even more, that had the power to affect Amelia’s future, to order that she be allowed to pursue her case, so that eventually money could be taken from American Litho and transferred to her, a few dollars to permit her to live a life with a modicum of dignity.

My class

In one of my courses this term, a course devoted to the reading of the great books of the common law, we spent an hour and a half discussing Reznikoff’s poem about Amelia in the context of the legal material I have discussed above. The poem affected the students greatly, particularly the way, at the word gently, the poem grabs the reader just as the revolving shaft entangled Amelia’s hair.

Nonetheless, when compared to Judge Bartlett’s opinion, the poem seemed to many of us, including, I must admit, to me, to be weak, a paltry thing. Judge Bartlett was the one who not only faced down the majority of the Appellate Division but, even more, implicitly rejected the views of fellow members of his various clubs, the corporate magnates who seemed to believe that their fortunes depended both on employing young girls and, sadly, withholding compensation for their injuries. The exercise of judicial power to protect the powerless seemed to most of us in that classroom to be far more important, and, in a way, beautiful, than the 21 lines that Reznikoff devoted to the matter.

In his final paper for the term, however, one of my students, Chris Sedefian, wrote that he found Reznikoff’s poem to be more powerful than the Bartlett opinion:

Here is this young girl, straight out of an orphanage, trying to please those in charge of her and to succeed in her job and appease her superiors (“the forelady had said, Keep the work off the floor!”). Then, all of a sudden, she suffers this horrible injury… and then that’s it, the poem abruptly ends. You are left with the following two lines – “… until the scalp was jerked from her head, and the blood was coming down all over her face and waist.” That is as powerful as it gets.

And so, I asked myself, what was it that Chris found to be so powerful in the poem? Of course Reznikoff no longer had the power to change Amelia’s fate. Bartlett’s opinion was an authorative proclamation, Reznikoff’s poem, in contrast, just a quick story one might tell to a friend. And yet in those few lines Reznikoff managed to avoid legal argument and extraneous detail and reduce the event to its one excruciating moment.

In other words, part of the power of Reznikoff’s poem is its focus. Without it, we would not remember Amelia today. If all we had was Bartlett’s opinion, the story would have vanished long since into the reporters, along with hundreds of similar cases and never again resurfaced. Amelia and her pain, and our pain as well, would have been gone forever. Reznikoff, by contrast, set the hook. By making poetry of this pain, the trauma works its way into us. For me at least, whatever I do for the rest of my life, Amelia will always be part of it. Though I cannot state it precisely, I feel that somewhere here is where we should locate the differences between the law and literature. Even though both take place principally in language, in fact, as this example demonstrates, sometimes in exactly the same language, they perform different tasks.

The color of her hair redux

So why is Amelia blonde?

Since part of the task of the poem is to allow us to relive this experience and rethink it, we have to be able to imagine the event as it occurred, and we can see her hair clearly only if we know its color. The poetic effect depends on our being able to see the shaft after it stopped spinning, the hair twisted around it, and Amelias bloody scalp. For that purpose, it would not matter what color her hair was as long as we can see it clearly.

In other words, the two words that Reznikoff added to the story, gently and blonde, are essential. The first draws us into the scene while the second locks us in without possibility of escape. Nothing in Judge Bartlett’s magnificent opinion manages that. It is partially due to these two words that I am writing this essay, and you are reading it.

My interest in the work of Charles Reznikoff (1894-1976), and in modernist poetry in general, arose while taking a course that Charles Bernstein taught at the University of Pennsylvania. For that course, and much else, I am deeply grateful to him.

Most of the material for this essay is taken from the record in Amelia’s case that was filed by her lawyers in the Court of Appeals. The record was published by the New York Bar Association in Court of Appeals 1910, vol. 8, and is available as a pdf and on the web here.

Other facts and descriptions used here have been gathered from a wide variety of sources on the internet. Due to the informality both of this essay and of the internet sources, it seemed too cumbersome to cite to them all. In most cases the facts are stated verbatim, so the original sources can be found by typing an appropriate search term into a search engine. Legal sources have been cited to the standard reporters.

NOTES

1 The color lithography was done by one of the printing companies Knapp later purchased when he formed American Litho. Since the atlases were bound by string and were not wire-stitched, they were not the Arbuckle books that Amelia was working with.

2 For the text of the statute, which has since been abrogated, see Martin v. Walker & Williams Mfg. Co., 91 N.E. 798, 799 (N.Y. 1910).

3 For the employer’s duty to warn employees, see Moran v. Mulligan, 97 N.Y.S. 7 (N.Y.A.D. 1905); Impellizzieri v. Cranford, 126 N.Y.S. 644 (N.Y.A.D. 1910).

4 Simone v. Kirk, 65 N.E. 739 (N.Y. 1902).

5 See Record at 15–68. There is discussion on the record during the second trial about the discrepancies in testimony between the two proceedings. Moreover, Justice Newburger, who presided at the second trial, indicated on the record that, on the whole there was little difference in testimony between the two trials.

6 See Brief for Respondent (last document in the Record).

7 Kirwan v. American Lithographic Co., 108 N.Y.S. 805 (N.Y.A.D. 1908).

8 The transcript from the trial is preserved in the record submitted to the Court of Appeal. See Record at 15–68.

9 Kirwan v. American Lithographic Co., 116 N.Y.S. 1139 (N.Y.A.D. 1909).

10 See Record.

11 Kirwan v. American Lithographic Co., 90 N.E. 945 (N.Y. 1910).

12 Bartlett’s biography is here and the decision is here. Judge Willard Bartlett was also on the Court at the time. The two Bartletts do not seem to have been close relatives.

13 For Reznikoff’s biography, see Charles Bernstein, “Reznikoff’s Nearness,” in My Way: Speeches and Poems 197–228 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1999). See also the biographical entry for Reznikoff on the website of the Poetry Foundation.