Slobodan Tišma: Two poems (with bio and commentaries)

translated from Serbian by Dubravka Djurić, Filip Marinovich, and Katie Fowley; edited by Charles Bernstein

BOOK CANDLESTICK ROOF

(published in 1973 in Letopis Matice srpske. a national journal from Novi Sad)

I had a hard day

so I started with parings

I liked that

because it was not similar to the spread of parings

When someone tells me I

Paint

If we are talking to one another

We don't understand each other

I open a book the book closes

The pages assemble the pages are similar

The pages are the same one page

One hundred pages two hundred sides

Empty with impressed letters

The book gets dirty but the book

Is no neat object. It is

Full of those kinds of words, in fact, pages,

For the book is empty: neat

are the words which mean something (if I am un-

ass-em-bled) and then a wider array

Which is over the book which simply

Abandons it since the book can or cannot

Be Ass-em-bled. That way it is shifting

And I hate it, it is changing my

Assembly. Books are always already old

I forget the book. Or, even better, when I say

The condition for something like that: break it down into pages

And hold every page separately so it has

With foresight over itself its own beginning

And end on the square of paper, with the absent

Page which is its pair. The body of paper shares meaning

And closes the square of paper into the square from both sides

But words don't answer to one another

They hold the paper discretely from them

Or when I read an empty book I jump over

the pages without effort

and with a laugh I fly high, I will allow myself

this way which doesn't belong in this text although

I can't resist jumping over these lines:

the high jumper is easy athletics on

TV, when the jumper jumps over himself

like an empty book

If, therefore, I open the book, I begin

with the first page carefully, it or which is empty

it or which is immaterial in form, the same as the next one,

That one which, as it stands against its

endless multiplications, is with its body

eternally returning to itself. And so in this world

pages multiply and the book grows

like bread

The book is for the poor. Allegory

Today I would write about the candlestick

which our friends brought

and which I commandeered

even though I think it was intended for my parents.

That candlestick was seen by many.

The candlestick can be found in my room

five years now. I was changing my mind

about what I could add, to write it up

I begin from the beginning like that as if you can begin

from the end

That is a story without its book

about the tinsmith who slipped in his sleep on the roof

of a house, in his sleep that happened many times

in all possible details which they could picture

a multitude of tiny finally meaningless shrug-offs

The happening was slowly emptying, there was less and less

remaining unwritten of the possible places of particularities

and his body accepted more and more strength

until finally it soaked up all the blood from the pages

of a book. And then the happening was written out, the body

closed so that it was possible to

approach him (without danger) and so that he wouldn't be

drawn into chance

During that time the book was slowly opening

unfolding its pages in a circle until

it connected the first with the last

T H E N the happening was written out

T H E N with the movement of a hand

T H E N with unclear thought

T H E N with a look into emptiness

T H E N all that went back to no consciousness

But the book fell into forgetting

fell toward emptiness

(it was growing) holding up the world (body)

He slipped in his sleep on a roof

He was dreaming that he slipped in his sleep on a roof

He did slip on a roof

KNJIGA SVEĆNJAK KROV

Imao sam težak dan

pa sam počeo sa strugotinom

To mi se dopalo

jer nije bilo slično širenju strugotine

Kada meni neko govori Ja

Slikam

Ako govorimo jedno drugom

Ne zaumemo se

Otvorim knjigu knjiga se zatvori

Listovi se slože listovi su slični

Listovi su isti jedan list

Sto listova dvesta stranica

Praznih sa otisnutim slovima

Knjiga se uprlja ali knjiga

Nije zgodan predmet. Ona je

Puna takvih reči, zapravo, stranice

Jer knjiga je prazna: zgodne

Su reči koje nešto znače (ako sam ne-

Raz-po-ložen) zatim jednog šireg niza

Koji je preko knjige koji je jednostavno

Napušta jer knjiga može ili ne može

Biti Raz-po-ložena. Tako ona se premešta

I ja je prezirem, ona menja moje

Raspoloženje. Knjige su oduvek stare

Zaboravim knjigu. Ili još bolje kada kažem

Uslov za tako nešto: rasparčati je na listove

I svaku stranicu posebno držati da ima

Sa smislom preko sebe svoj početak

I kraj na kvadratu od hartije, sa odsutnom

Stranicom koja je par. Telo hartije deli značenje

I zatvara kvadrat u kvadrat sa obe strane

Ali reči ne odgovaraju jedna drugoj

Na raspolaganju drže telo hartije

Ili kad čitam praznu knjigu ja preskačem

stranice bez napora

i uz smeh visoko se vinem, dozvoliću sebi

ovaj put što ne spada u ovaj tekst ali

ne mogu odoleti da ne preskočim i ove redove:

skakač uvis što je laka atletika na

TV, kada skakač preskoči sebe

kao praznu knjigu

Ako, dakle, otvorim knjigu, počinjem

sa prvom stranicom pažljivo, koja je prazna

koja je nematerijalna oblikom, istovetna sledećoj

Ona kao jedna stoji nasuprot svom

beskonačnom umnožavanju, svom telu koje

joj se večito vraća. Tako u ovom svetu

stranice se umnožavaju i knjiga raste

kao hleb

Knjiga je za siromašne. Alegorija

Danas bih pisao o svećnjaku

koji su doneli naši prijatelji

i koji sam ja prisvojio

premda beše namenjen mojim roditeljima

Taj svećnjak su videli mnogi.

Svećnjak se nalazi u mojoj sobi

već pet godina. ja sam se predomišljao

šta bih mogao da dodam, da dopišem

Počinjem iz početka tako kao da se može početi

s kraja

To je priča bez svoje knjige

o limaru koji se u snu okliznuo na krovu

kuće, u snu to se ponavljalo mnogo puta

u svim mogućim detaljima koji su odslikavali

mnoštvo sitnih gotovo beznačajnih odstupanja

Događaj se polako praznio, sve je manje

ostajalo neopisanih mogućih mesta pojedinosti

a njegovo telo primilo sve veću snagu

dok najzad nije pokupilo sve veću krv sa stranica

knjige. I onda događaj se ispisao, telo se

zatvorilo tako da mu je bilo moguće

priči (bez opasnosti) a da se ne bude

uvučen u slučajnost

Za to vreme knjiga se polako otvarala

razvijajući stranice u krug sve dok se nije

spojila prva sa poslednjom

ONDA događaj se ispisao

ONDA sa pokretom ruke

ONDA sa nejasnom pomisli

ONDA sa pogledom u prazno

ONDA sve se to u nesvesti vratilo

Ali knjiga je pala u zaborav

padala prema praznini

(rasla je) podupirući svet (telo)

On se okliznuo u snu na krovu

On je sanjao da se okliznuo na krovu

On je sanjao da se okliznuo u snu na krovu

On se okliznuo na krovu

LIKE SOMEONE

(published 1970 in Novi Sad, student newspaper, Index)

1. like when

2. or toward the same

3. how

4.

5 (yes, yes)

6. and always I am in everything

7. and always alone when in everything

8. and always I am when in everything different

9. and always I am when in everything different from itself is

10. and always

11. itself is

12. is it over there

13. that is that

14. this is not this

15. this is that

16. this is not that, but is there

17. but it's long since then

18. long time like that

19. that is that, if it is not here

20. I am not I

21. I is I

22. who am I

23. what is not I

24. who am I not

25. who is not I

26. who is I

27. nothing is like that now

28. as if before

29. with no one is it like that in everything

30. like once

31. toward

32. but and after, or only after

33. and that

34. so that out of those once

35. that's how it is

36. well

37. and not like once

38. like now not at all

39. once and already – here once is

40. with whom is then behind these very same

41. with all that more then before

42. never before

43. sometimes before those

44. sometimes very close

45. sometimes again

46. and so on

47 always although again

48. never

49. where is all that or when

50. now

51. and what now

52. nothing

53. nothing is too much

54. or for now

55. for now like that

56. nothing is too much there

57. with that

58. as always

59. always before once

60. if I am too much in that

61. without any or at least in general

62. in general

63. many similar

64. arent’t you not

65. are [you] already from here

66. once

67. one without the others

68. not for anybody

69. from here to there

70. isn’t it

71. on

72. again

73. from there

74. from then when no one with no one is not

75. someone

76. once in one

77. one in other

78. without all that

79. almost enough

80. and like it

81. almost all

82. almost always no

83. almost always here under the same

84. why not

85. like that

86. above all

KAO NEKO

1. kao kada

2. ili prema istom

3. kako

4.

5. (da, da)

6. i uvek sam u svemu

7. i uvek sam kada u svemu

8. i uvek sam kada u svemu različito

9. i uvek sam kada u svemu različito od sebe je

10. i uvek

11. sebe je

12. da li je tamo

13. to je to

14. ovo nije ovo

15. ovo je ono.

16. ovo nije ovo, ali je tamo

17. ali je dugo od tada

18. davno tako

19. to je to, ako nije tu

20. ja nisam ja

21. ja je ja

22. ko sam ja

23. šta nije ja

24. ko nisam ja

25. ko nije ja

26. ko je ja

27. ni sa čim nije tako sad

28. kao da pre

29. ni sa kim nije tako u svemu

30. kao nekad

31. prema

32. ali i posle, ili samo posle

33. a to

34. da se iz tih nekad

35. tako je to

36. pa

37. i ne kao nekad

38. kao sad nikako

39. jednom i to već

40. sa kim je tada iza onih istih

41. sa svim tim više od nekad

42. nikad pre

43. nekad pre tih

44. nekad veoma blizu

45. nekad opet

46. i tako

47. uvek iako opet

48. nikad

49. gde je to sve ili kada

50. sad

51. i šta sada

52. ništa

53. ništa nije suviše

54. ili za sad

55.za sad tako

56. ništa nije suvuše tamo

57. sa tim

58. kao i uvek

59. uvek pre nekad

60. sako sâm suviše u tome

61. bez kakvih ili bar uopšte

62. u opštem

63. mnogo takvih

64. zar više ne

65. da li (si) već tako odavde

66. jednom

67. jedno bez drugih

68. ni za kog

69. odavde dovde

70. zar ne

71. o

72. ponovo

73. odande

74. od kada niko ni sa kim nije

75. neko

76. jednom u jedno

77. jedno u drugom

78. bez svega toga

79. skoro dosta

80. i kao to

81. skoro sasvim

82. skoro uvek ne

83. skoro uvek tu pod istim

84. zašto da ne

85. tako to

86. iznad svega

Notes for LIKE SOMEONE

Everything in a statement that may be subject, object, predicate is not a word.

Nouns are not words.

House, for instance, is not a word, or is less so than others.

Also*, verbs may not be words.

Adjectives?

Real words are, for instance, LIKE, WHERE, OR, ALWAYS, WITH.

I always say: seen from the outside.

What does that mean?

This is imagined from outside or inside . . . But not to the statement.

Outsideness is aimless and insignificant.

That would be expressed.

Language is not EVERYTHING.

For this note I cannot take responsibility.

Everything that is in it is probably wrong and senseless and worse than that: arbitrary.

Humiliated long ago, LIKE is one word very mistreated and wrongly used all the way till today.

*In the original Tišma wrote TaKôDje whish means also, but the word usually is written takođe, with the letter đ using some older transcriptions. This spelling is a reference to the conceptual group KôD, which means code, of which he was a member from 1970 to 1971.

Beleška uz KAO NEKO

Sve što u jednom iskazu može biti subjekt, objekt, predikat nije reč.

Imenice nisu reči.

Kuća, na primer, nije reč ili je to manje od drugih.

TaKôDje, glagoli, možda nisu reči.

Pridevi?

Prave reči su na primer KAO, GDE, ILI, UVEK, SA.

Ja uvek kažem: spolja gledano.

Šta to znači?

Ovo je zamišljeno spolja ili iznutra... Ali ne do iskaza.

Spoljašnjost je neusmerena i nevažna.

To bi bilo ispoljavanje.

Jezik nije SVE.

Za ovu belešku ne mogu preuzeti odgovornost.

Sve što je u njoj, verovatno je pogrešno i besmisleno i još gore od toga: proizvoljno.

Ponižena još davno, KAO je jedna reč mnogo zlostavljana i pogrešno korišćena sve do dana današnjeg.

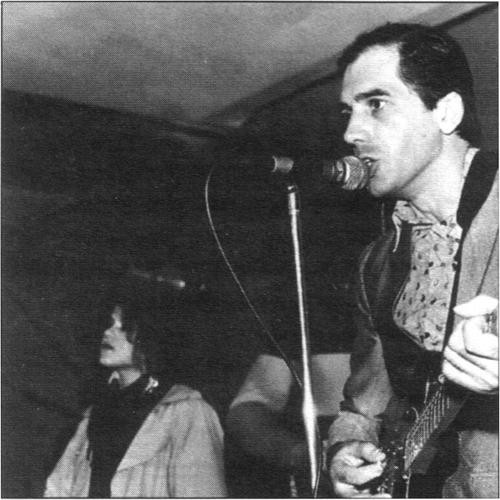

Slobodan Tišma, was born in 1946 in Stara Pazova and lives in Novi Sad (Serbia). He studied literature in Novi Sad and Belgrade. Tišma was active as conceptual artist and rock musician. He was on the editorial boards of the magazines Index and Polja, magazines which presented for the first time in a socialist country translations literary theory and essays on new art (for example one issue around 1970 focussed on conceptual art). He was also involved with New Tendencies in Literature, Philosophy, Art, and Tribina mladih (Tribune of Youth), one of the important cultural centers of socialist Yugoslavia, where new artistic practices were introduced. For several years, he worked on TV Novi Sad for the cultural TV programs “Kulturni magazin,” “Videopis,” and “Sazvežđe knjiga.” Tišma has published six books of poetry books: “Marinizmi” (1995), “Vrt kao to” (1997), “Blues diary” (2001), “Pjesme” (2005) and a work of prose, “Urvidek” (2005), which received the “Stevan Sremac” award, as well as a novel, “Quattro stagioni” (2009) which received the “Biljana Jovanović” award. There were sections in his work in Gradina in 2007 Polja in 2010. He is a member of Serbian PEN and the newly established (post-Milošović) Serbian Literary Society.

COMMENATARIES

Dubravka Djurić sent me rough translations of these three poems and asked if I might help making a final version. Vanda Perovićworked with her on making the intitial versions.Katie Fowly and Filip Marinovich agreed to help, even though Katie and I knew no Serbian. We had a lengthy, lively email exchange, though it would have been better if we could have met in person, which was not possible. One issue that arose was whether to give the gender to such nouns as “book” in the first poem (Filip suggested the pronoun should be “she” in the first poem, Dubravka demurred). In the end issues of social framing came to the fore, with Filip and Dubravka reading the poems differently, partly reflecting their different perspective in life, Dubravka from Belgrade, and in touch with Tišma and Filip in New York. –Ch. B.

Filip Marinovich

NOTES ON TIŠMA'S TONE

The tone as I see it is a salty parody of Tito Communist regime grammarschool teacher police state arrogance and condescension.

Like a middleaged ruffled professor, a little drunk on loza at the Plato Cafe, jawing at disciples.

There is contempt for authority in this feigned stupidity.

But also, a certain empathy for the trapped buerocrat.

The tone is very similar in fact to Dostoyevsky's THE DOUBLE.

Hallucinatory HYSTERIA moving in and out of the hero's control.

It needs to sound like one middle finger clapping.

These poems are an act of alchemy upon the buerocratized party-speak of Tito era Yugoslavia.

They are engaged in re-eroticizing a sterilized tongue.

Therefore, GENDER is crucial.

These poems are also LOVE POEMS, strangely enough.

So when the gender turns to femenine, this move MUST be preserved if at all possible, even if it sounds sexist, because, well, it IS a little sexist, but it is also terribly bluesy and part of what the poet is saying.

He's turning language into a lady to win her back.

AND also criticizing that act at the same time, or offering it up for critique, debate, laughter.

Also there is a kind of word-echo-chamber effect in here that wonderfully captures something of the cavelike social claustophobia of those times (of these times too!) So I've tried to allow the words to echo as much as possible.

So I've done all I can to bring it closer to the original Balkan blues.

Dubravka Djurić

Tišma's work, like Vladimir Kopicl, is part of Vojvodina's experimental artistic and poetry scene, which was severely marginalized within the canon of Serbian poetry. During Tito's rule, Vojvidina was an autnomous province, like Kosovo and a part of Yugoslav Socialist Republic of Serbia . It was populated by, and is still populated by, different ethnic groups: Serbians, Hungarians, Romanians, Croatians, etc. This multilingual environment fostered an experimental poetic practice. Tišma was a important member of Novi Sad's conceptual art group KOD (CODE), which did land art, organized happenings, as well as creating a range of art objects. His poetry might well be read in the context of conceptual art. Joseph Kosuth, Art & Language, Ian Wilson, and others were translated, and also exhibited in the Yugoslavian Student Cultural Centers in Belgrade, Ljubljana and Zagreb. Tišma points to the influence of high modernism and avant-garde poetry as it is articulated in Italy and elsewhere in the West. It is a mistake to read his work primarily in Cold War terms, with Tišma playing the part of a wily dissident. Tišma’s poetry is political in a subtle way – as a politics of poetry – which means that it doesn’t deal with political discourse at all. That makes it implicitly political, dealing with the “pure” artistic expression. His work is neither coding nor declaiming its political dissidence. Rather its poetic politics is expressed by its deep aversion of moderate socialist modernism, which prevailed in some parts of former Yugoslavia including Serbia, since late 1950s, with Vasko Popa as a typical example. [See Djurić’s discussion of Popa here.]

At the time when Tišma wrote “LIKE SOMEONE,” Yugoslavian poetry magazines were publishing translations from the important Italian anthology I Novissimi from 1961. Tišma points to the Edoardo Sanguineti, Elio Pagliarani, and Nanni Balestrini. Pagliarani's “La ragazza Carla” was considered to be new “Waste Land.” Balestrini's cut-up technique was significant. For Tišma, this was the peak of Italian and European modern poetry, high modern, experimental, avant-garde. In a recent conversation, Tišma said that “LIKE SOMEONE” stressed the reduction of language – a sort of purification, stripping language of all tropes, of all the frills of poetic language, moving toward something like pure abstraction. But something unexpected happened in the poem. Instead of stripping away emotions and senses, amazingly, an unexpected pathos was revealed. About “ROOF,” Tišma said that he was dealing with objects. He pointed to the phenomenological approach in French poetry from Mallarmé to Ponge and to its concern for abstracted objects. Tišma saw this as hermetic: the object is derealized. Since every object has a history, a story, the intention was to detach the object from these contexts. The story may appear, but if it does, it appears as something detached. In the poem, Tišma tells the story of a candlestick, how it comes into the poet’s focus. The book is also treated as an abstract object. The book is imagined as having no figurative meaning. It is treated as a physical object in space and time, a square thing. Inside the book, there is a language which fills it, and which carries forms, and figures of life, but all of that is contrary to the book’s objectness. Finally, “ROOF” engages the relation of language and the body. The figurativeness of language suggests a changeable structure, while body is static and unchangeable. The poem takes on a process of derealization through the language. This is what Tišma told me: Language is not the tool of communication. When we speak, we don’t understand each other.

Filip Marinovich

I use my own manic-expressive experiences in Yugoslavia/Serbia, and the experiences of my grandparents (who were spied on their whole adult lives,) and those of my parents, uncles, and aunts, who fled the Tito regime, as well as the many people whom I spoke to in Yugoslavia/Serbia over the years, to look at what Tisma's poetry is doing, his disclaimers notwithstanding. However, I admit I am Belgrade-centric, since that is where I spent most of my time on my visits to my family. Therefore, I am probably projecting a certain Belgrade/New York-esque narcissism onto the poems, and hearing things in them that are not there. But then again, how can they not be there, a poem exists between at least two people, and in that gap hermeneutical maneuvers can, even when "incorrect," be ways of finding a portal to the right-now-ness poetry can translate, or stab at, with all its tuning forks of Jetztzeit (Nowtime) lightning.

•

This move to gender-neutral, I can see how it's necessary for clarity, but there is unfortunately some sexual politics we are missing, perhaps they are untranslatable, for instance:

Knjiga se uprlja ali knjiga

Nije zgodan predmet. Ona je

Puna takvih reči, zapravo, stranice

Jer knjiga je prazna: zgodne

Su reči koje nešto znače (ako sam ne-

The book gets dirty but the book

Is no easy subject. She is

Full of those kinds of words, in fact, pages

Because the book is empty: easy

Are the words which mean something...

that's my translation, what I was getting at is that "Ona" means "She" and "Zgodan" and "zgodne" don't just mean "convenient" or "neat" but also "sexy" "easy" and "attractive". Maybe "sexy / are the words which mean something (if I am not-/in-the-mood)" would come close to the playfullness the poem suggests to me. "ne-ras-polozen" definitely sounds to me like he's playing with sexual politics, being "in the mood" or not. But this is perhaps untranslatable, like "TaKoDje."

Dubravka Djurić

I continue to object to the use of she for it in this case: because English doesn't give gender to nouns, it adds something misleading to the translation of this poem. But my view here is colored by current language politics in Serbia. Conservative and politically reactionary linguists, who try to adjudicate language standards. For the last almost 20 years they have attempted to stop a feminist move to coin more female forms based on the already existing female forms for doctor, teacher, or professor. We created female forms also for psychologist, sociologist, translators, and philosopher. Lately, some of these linguists say that of these new words are used in practice, that can be noted.

Dubravka Djurić wishes to thank Vanda Perović for help on translating both poems.