N. H. Pritchard: 1978 interview

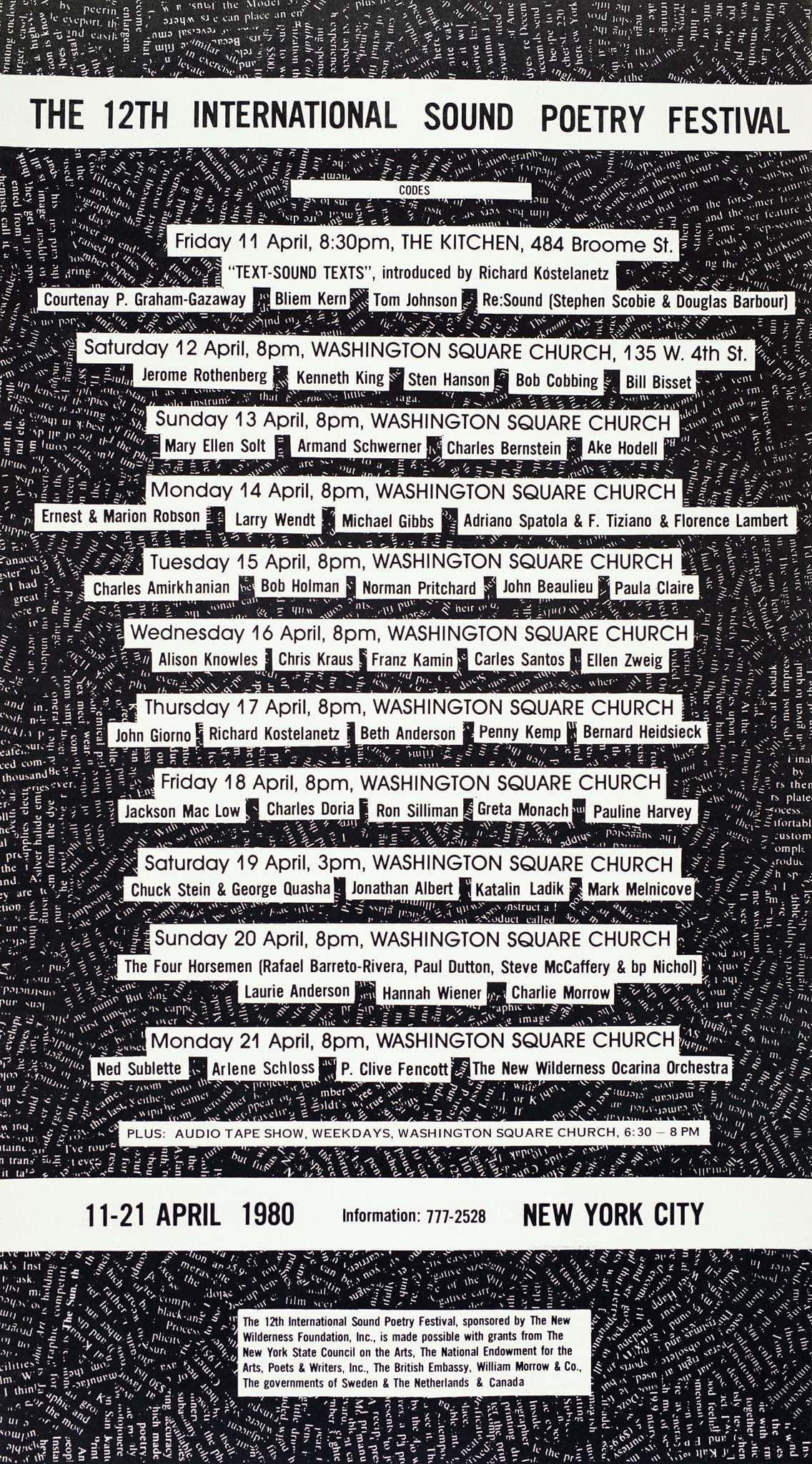

Judd Tully interviewed N. H. (Norman) Pritchard on Sept. 11, 1978. The ninety-minute conversation is informative and engrossing, offering more information about Pritchard than has been previously available. Pritchard was a poet in the CETA / Cultural Council Foundation Artists Project in New York and Tully, a CETA writer, interviewed him as part of the program. PennSound is happy to make this recording, made as part of the Artists Project, available, thanks to Tully and to Molly Garfinkel of CityLore. Records of Pritchard's CETA assigments are here. For upated information on Pritchard's manuscripts, see David Grundy's report.

Part one (47:41): MP3, wav

Part two (43:08): MP3, wav

Computer-generated, partially edited, transcript (for reference only): pdf

During the course of the interview, Pritchard reads an early poem and two recent poems (at the beginning of part two):

“… in September ’63, I wrote a poem entitled ‘AsWeLay.’ And that poem … was a major turning point in my career. I wrote it in a state of trance.”

“AsWeLay” (from The Matrix: text) (2:51): MP3

“So I wrote that when I was about 23, in a state of trance. In other words, I awakened … from sleep into a state of trance, I went to my desk, I started writing this. I was chatting as I was writing. And then after I completed, I awakened. And when I wrote that poem, I knew I said, well, Norman, that’s it. I knew at that point on, I knew that I would be able, I was destined to be able, to make a contribution in my field.”

“the first lady …” (May–June, 1978) (3:30): mp3

“… each one of those is numbered, by the way. … It’s a particular form. It’s one through one hundred, five on a page.”

“and I somewhere” (June 1978) (3:07): mp3

Also by Pritchard on PennSound: “Gyre’s Galax,” late 1960s (1'51"): MP3

Pritchard’s two books were published in 1970 and 1971, when when he was just over thirty. You can read them free, online at Eclipse, thanks to Craig Dworkin. For my introduction to Pritchard, go to this Jacket2 post.

Pritchard’s two books were published in 1970 and 1971, when when he was just over thirty. You can read them free, online at Eclipse, thanks to Craig Dworkin. For my introduction to Pritchard, go to this Jacket2 post.

DAP is distributing new editions of this work from Primary Information /Ugly Duckling Presse and DABA.

Here’s my blurb for DABA: “Norman Pritchard, gloriously inventive, iconoclastic American poet of the 1960s, combines syntactic wildness, visual daring, rhythmic concatenation, and conceptual scatting. Pritchard hops, skips, and jumps with his syncopated words. Yet in spite of, or maybe because of, his poetics of multiplicity and ambiguity, his work has for too long flirted with obscurity. These poems, brought back to print, jolt us, jam us, join us.”

For more on Prithcard, see Paul Stephens’s essay on Pritchard in Jacket2, Craig Dworkin’s essay in The Radium 0f the World (2021), and David Grundy in Artforum on the new reprints. See also Ishmael Reed on Pritchard in The Brooklyn Rail; Anthony Reed, Freedom Time: The Poetics and Politics of Black Experimental Writing; Lorenzo Thomas, Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric Modernism and Twentieth-Century American Poetry, Aldon Nielsen, Black Chant: Languages of African-American. (Pritichard is also in Nielson and Lauri Ramey’s anthology, Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone: An Anthology of Innovative Poetry by African Americans).

At the end of the 1978 interview, Pritchard mentioned several unpublished works, including a large cultural history of America (an anthology). The fate of these mss is unknown.

Molly Garfinkel of CityLore provided, and corrected, the transcription of the digital version of Tully’s cassette. She is at work on documenting the CETA/CCF Artists Project.

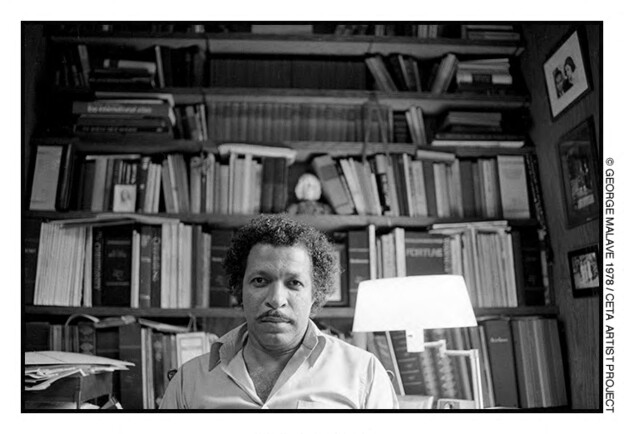

The photographs of Pritchard are courtesy George Malave, taken Sept. 6, 1978. The photo below was taken in his backyard garden. Malave was a CETA/CCF photographer at the Artists Project. I am grateful to him for making these photographs available. The photographs may not be reproduced without his permission

Preliminary notes:

Born: October 22, 1939

“My father was a physician and surgeon born on the island of Jamaica, in the West Indies. And my mother always is a homemaker who had spent her early years in banking and was born on the island Trinidad. I have one sister, Diane Carol, who was born in 1944. And creatively, she’s a sculptor.”

Pritchard attended the Downtown Community School, near St. Mark’s Church in New York, and then St. Peter’s School in West Chester, PA (an Episcopal prep school). He lived, when young, at 1878 Seventh Avenue, at 104th Street, where his father had a medical office, which he kept after the family moved to the Bronx, and then, in 1948, Crown Heights.

Pritchard started at NYU (Washingon Square College), where his father had graduated, in 1957. “It was in a period when Greenwich Village was booming creatively, particularly for poets. Ginsberg and Corso and Kerouac would come in from the coast. … In the four-year period that I was at … at NYU, I met … every major painter and poet in America. I can recall hours upon hours of rapping with de Kooning and Motherwell and Kline and Rothko and Guston. … Rapping with Paul Blackburn and Oppenheimer and Ginsberg and Frank O’Hara. It was a very unique experience in the Cedar Tavern.”

He became poet-in-residence at Friends Seminary in 1968 or 1969 and also taught at the New School from about 1969 to 1975. 1969, he says, was his big year: he got his first book contract (for The Matrix: Poems 1960–1970, published by Doubleday in 1970) and also a big grant for younger writers from the Abraham Woursell Foundation (Vienna and New York).

He married Sarah Dickinson in 1966; they separated in 1970 and were divorced in 1972. They had an apartment at 112 East 73rd St. (Manhattan). From 1972–1974, Pritchard reports that he lived with “Mrs. Duncan S. Ellsworth Sr.” — formally Helen Waters (Elting) (1914–2007) — at her estate in Salisbury, CT. Duncan S. Ellsworth Sr. died in September 1967; Pritchard says he “owned” the New York Review of Books, although it’s officially their son, A. Whitney Ellsworth, also of Salisbury, who was the publisher of NYRB (he died in 2011). The Ellsworths also had an apartment at 1 Sutton Place South. Pritchard notes he kept his E. 73rd street “studio.” It’s striking that Pritchard was so close to these cultural and financial elites at the time. Helen Ellsworth “was at the very center of literary life in America. Because there is … no more formidable journal in our country than the New York Review of Books. So I find myself right in the center of literary power. And, quite frankly, I was very much oblivious to it. When I say oblivious, and I was, needless to say, cognizant of it, but it did not affect me. I was very much removed from it. It held … no particular interest for me.”

He married Sarah Dickinson in 1966; they separated in 1970 and were divorced in 1972. They had an apartment at 112 East 73rd St. (Manhattan). From 1972–1974, Pritchard reports that he lived with “Mrs. Duncan S. Ellsworth Sr.” — formally Helen Waters (Elting) (1914–2007) — at her estate in Salisbury, CT. Duncan S. Ellsworth Sr. died in September 1967; Pritchard says he “owned” the New York Review of Books, although it’s officially their son, A. Whitney Ellsworth, also of Salisbury, who was the publisher of NYRB (he died in 2011). The Ellsworths also had an apartment at 1 Sutton Place South. Pritchard notes he kept his E. 73rd street “studio.” It’s striking that Pritchard was so close to these cultural and financial elites at the time. Helen Ellsworth “was at the very center of literary life in America. Because there is … no more formidable journal in our country than the New York Review of Books. So I find myself right in the center of literary power. And, quite frankly, I was very much oblivious to it. When I say oblivious, and I was, needless to say, cognizant of it, but it did not affect me. I was very much removed from it. It held … no particular interest for me.”

He says that he had an important relationship with photographer Beverly Pabst (1918?–2007?) starting in 1975. A few years later, Pritchard found himself working in a government jobs program, the CETA Artists Project. He is reported to have died in 1996. Little is known about those last twenty years.

In the beginning of the interview, Pritchard talks about how his revolutionary poetics and politics are intertwined: “I often think that poets are the most limited of the creative artists, in as much as their vision tends to be so self-centered that this equidistance from art form to art form is not enjoined. And a great deal of the things that I have to say publicly speaks directly to this kind of revolution, which transcends poetry. I’m involved with a revolution that’s going to change the form of the book. I’m not sufficiently satisfied with a poetic revolution. I’m concerned with the revolution that involves the transformation of the book itself. Within poetry, you have two very great problems in America. One is the problem of racism. Racism, which, of course, is the most formidable problem in America, always has been, because the nation was founded … on the most horrific race war in the history of mankind. So, that fact, where white people, were killing red people. … This racial problem, in the hemisphere, is … the major problem, which affects us spiritually, affects us culturally, right across the board. The other problem is that of the reactionary, and within the poetry establishment within the literary establishment, we have this reactionary clinging to the past, I won’t say tradition, because tradition and the past in my view are two different things. Tradition, true tradition, is not temporal. So, when I talk about revolution, publicly, privately, I really mean revolution. … What I’m saying about a poetic revolution: I mean, changing the book itself. So when you open into this world, you are involved in … something that is … in which you can indeed be reborn. Like … what McLuhan calls the Gutenberg Galaxy.”

Pritchard cites the influence of Mallarmé, above all, but also his engagement with Shakespeare, Coleridge, Baudelaire, and de Maupassant. While he notes his appreciation of many fellow writers, the only contemporary he names in this context is Richard Brautigan. “I’ve always been very serious about my work. Far, far, far in advance of, like anybody I’m … involved with, even Ginsberg, who I love dearly. I mean I’m just like someplace else. I don’t know how to explain. And I’ve always been this way.”

“About 1970, I began speaking in tongues,” Pritchard says in the interview. “Chanting and voices just would come upon me. At first it frightened me. And then I began to seek out monks and priests and rabbis and nuns and hermits who were experiencing the same, and began slowly to make sense to me. There’s a movement called the Charismatic Movement, which … fundamentally transcends, all religions. Before I’m a poet I’m a mystic. So that these tongues, these voices which are always with me. The ancient. I don’t know where it comes from.” Pritchard notes that, over the next several years, he performed musical concerts to large audiences. Ornette Coleman would often come. Despite the jazz connection, he stopped performing, finding the spiritual experience too private.

“I must say that creatively, I’m in a state of ecstasy, and have been for very, very many years. … I genuinely feel privileged, that God has given me this because in my life, my work comes first, after God.”

NY Times, November 13, 1966

n

n

Pritchard with Tully/ Photo by George Malave