Runa Bandyopadhyay on Pitch of Poetry

Rhythm of Literary Derangement: Pursuit of Karma Yoga

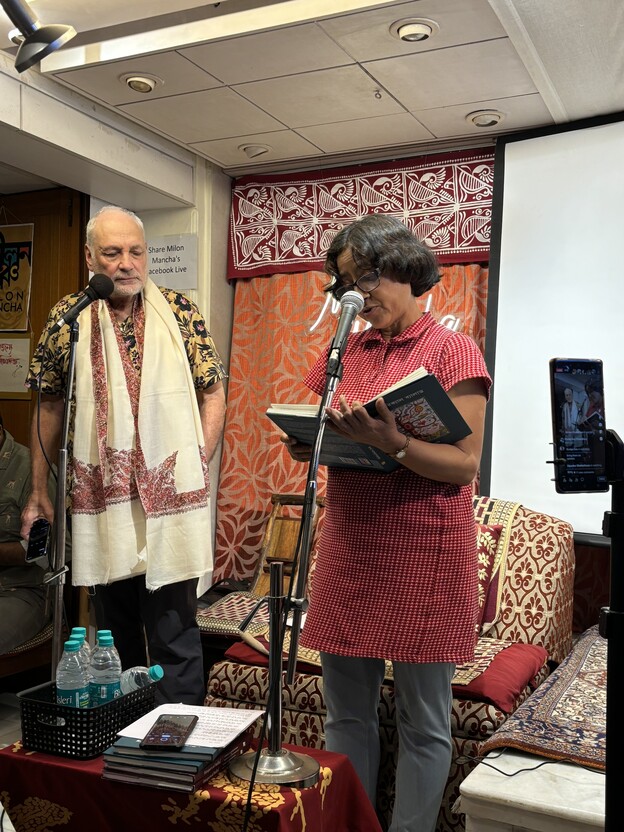

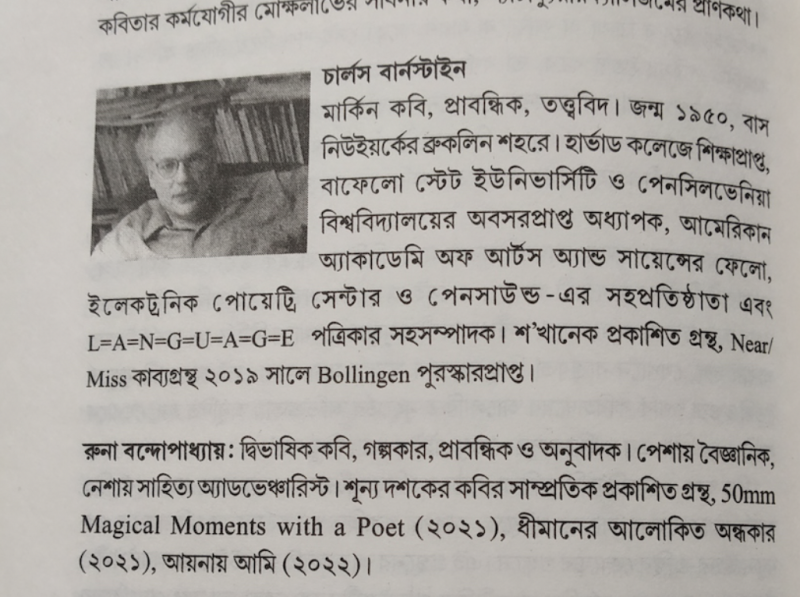

Runa Bandyopadhyay recently published an extended review of Pitch of Poetry in Chhapakhanar Goli, 21st year issue, April 2024 (W. Bengal). For this page, she adapted and extended that review to create a new essay in English, published here for the first time. I am publishing it as part of my ongoing, transformative, collaboration with Runa, outlined in the links at the end. I am also happy that this review comes just at the time my subsequent (mostly essay) book, The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays & Comedies has been published because Runa's incive elaborations provide a perfect introduction to that book. As I say in our recent book, Pataquerical Ballad, our collaboration is not transnational but non-national –– nomadic as Pierre Joris would have it. Its "no place" is our place, and perhaps, as you read this, your place too. --Ch.B.

•••••••

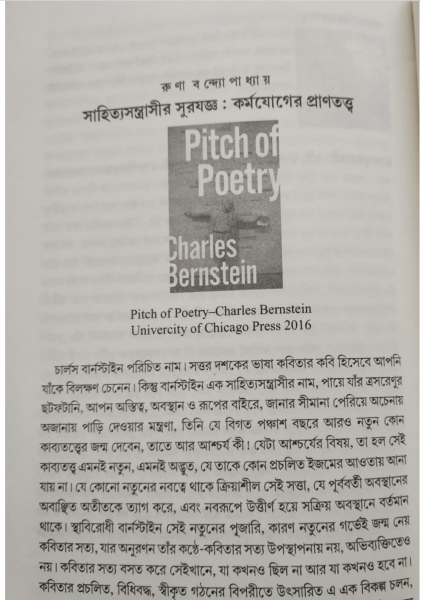

Runa Bandyopadhyay: Rhythm of Literary Derangement: Pursuit of Karma Yoga

Pitch of Poetry (University of Chicago Press, 2016)

Charles Bernstein, a familiar name. You might know him as a language poet of the seventies. But Bernstein is not only a poet but also an adventurist, originated from Latin adventūrus (“about to arrive, “about to happen”) that suggest the willingness of a person to go where he hasn't been before and do things he has never done, which is in resonance with Bernstein, “I do….what hasn’t been done in this way before,….what pushes me a little further than I have gone”[1]. He always seeks to elevate himself to be in an excited state to attain the escape velocity— to go beyond his own existence, own position, own forms— to go anywhere, out of the world. Therefore, it is not surprising that he will give birth to a new poetics in the last fifty years. What is surprising is that his poetics is so new, so strange, so queer, that it cannot be brought under any conventional ism but his own pataquericalism.

‘New’ is an entity that goes beyond the tainted past of the previous position to enter into the present and remains in its active state looking towards the future. Adventurist Bernstein believes in this new, because truth of poetry is born in the womb of a new, as Bernstein in Recalculating, “The truth of the poem is neither in the representation nor the expression. Its truth dwells in what has never been and what will never be” (83).

But what his Karma Yoga? The word Karma is derived from the Sanskrit Cre — “to do”. And English dictionary says that ation is an action. So, cre-ation is to do an action. All action is Karma. As nature is composed of three forces — Sattva (equilibrium), Rajas (action), and Tamas (inaction), every man has to deal with these three forces, where equilibrium means the balance between action and inaction. That is what Karma Yoga of a man. But there is a caution about this from Śrīmadbhagavadgītā[2]— ‘Thy right is to work only, but never with its fruits; let not the fruits of action be thy motive, nor let thy attachment be to inaction’(hymn:2.47). Attachment to inaction resists the negation of limiting adjuncts. In other words, we must celebrate not the freedom from action but the freedom in action, not the life from withdrawal but the life in engagement.

The objective of a man, involved in any kind of activity, is to understand one’s own self, not to stand under but to Know thyself, and then going about one’s ergon (action) with joy, not by following any official morality but by his own ethical judgement. This action through self-ascension for progress leads to freedom from the self-binding bondage, where freedom gives the power of realizing the meaning of life, the values of the self and others.

But our dominant poetic world replaces this value with moral-value and confine itself to the bondage of the old morals and fails to free itself from imitating, mirroring or repeating the fixed predetermined universally accepted standards of poetry. From their confinement zone of morality official verse culture deacknowledges all the dreams, imaginations and aspirations of new poetics, new inventions, and new aesthetic adventures, to acknowledge only their official moral-value, and hence stigmatizes others as odd and awkward, and tries to marginalize them. That is where Bernstein’s Karma Yoga is in action with his aversive process of bent studies, to respond to the bent, mute, and marginalized, with his rhythm of ‘aversion of conformity’ to official verse culture, for the freedom of poetry from the poetic prison.

Being a literary deranger Bernstein surely creates explosions but it is an explosion of thoughts, created by the arm, not to harm physically but psychologically, with the paroxysms of his literary in(ter)ventions —not only an invention but also intervention into language, into ideas, into the inner realm of thoughts, ‘like sparks, ride on winged surprises,/ carrying a single laughter’[3].And the book of poetics that provides the crucial space for his pataquericalism is Pitch of Poetry, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2016, where pitch is not only the sound of poetry but also the attack of literary derangement.

What is the catalyst behind the naming of the book? It is the Autobiographical Exercises of American philosopher Stanley Cavell— A Pitch of Philosophy[4]. Bernstein’s poetics performs neither continuity nor uniformity, rather inconsistency, to echo Stanley Cavell’s idea of pitch— ‘temporary habituation’ and ‘unsettling motion’, as Bernstein quoted, to blur the boundaries between poetry and philosophy, as he says,

I don’t see the distinction between truth claims, on the side of philosophy, and affective expressions, on the side of poetry; perversely, I am interested in affective expressions in philosophy and truth claims in poetry’[5].

That is how Pitch of Poetry is attuned to pataquericalism, a philosophical investigation process into language of poetry. It is a book of poetic theory, and a theory bears the essence of an ever-evolving entity of a matter or subject. His pataquericalism with a pataquerical imagination is a promise of achieving an imaginary space to implode the periphery of the rigid orthodox system. However, this achievement needs a theory, its implementation plan, belief in the plan of action, and its performance accordingly. Pitch of Poetry creates the active field in the pursuit of this performance.

L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E

'Pitch of Poetry' is mainly divided into four chapters. L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E is the first one. Yes, it is that renowned magazine L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, started in 1978, coedited by Charles Bernstein with his contemporary poet Bruce Andrews. The chapter provides an in-depth review of the idea of publishing this magazine, the history of its development, and how the American poetics has been developed significantly through the collective efforts of its associated language poets. Language poetry celebrates the “materiality of the signifier” to explore “the politics of the referent” for “showing how it’s constructed, showing what’s missing, showing what’s excluded, showing how the references of language are distributed”[6], as explained by Andrews in his interview with Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich in Jacket2. It’s to break down the difference between the signifier and signified and to fuse them onto one plane. It’s an alternative way to create meaning by the text where text are themselves signified, and to create a different types of reading experience by the sound and visual appearance of the text that acts as material signifier. Bernstein and Andrews have provided a summary of their editorial project in L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E,

Throughout, we have emphasized a spectrum of writing that places its at tention primarily on language and ways of making meaning, that takes for granted neither vocabulary, grammar, process, shape, syntax, program, or subject matter. All of these remain at issue. Focusing on this range of poetic exploration, and on related aesthetic and political concerns, we have tried to open things up beyond correspondence and conversation: to break down some unnecessary self-encapsulation of writers (person from person, & scene from scene), and to develop more fully the latticework of those involved in aesthetically related activity.[7]

L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E magazine was not for poetry but for “activist poetics—thinking with the poem”, where “poetics was conceived as reflections, investigations, and speculations by and for poets”. Language poets emphasized on “nonexpository approaches to critical thinking, discursive writing where the compositional imperatives of poem making were manifest”, as Bernstein says (PP:63).

Poetry is an aesthetic creation, and for any creation there is a Nature’s ironclad law of renewing. There is no exception for Language poetry too. Human consciousness is the most supreme achievement of Nature in her long course of biological evolution from inert matter to Homo sapiens. However, consciousness is always in a state of being elevated. For the realization of this elevating characteristic of consciousness, Nature applies the give and take strategy for her crowning creatures through her own ironclad law. To continue her path of evolution, Nature gives human being the inner urge of procreation with a higher level of consciousness that one must obeyed to survive. In return, human being finds the delight of fulfilling his desires, implanted by Nature herself. In other words, human being fulfils Nature’s law of renewing old one in the process of creation and finds the meaning of life, which is the reward given by Nature.

Therefore, following the Nature’s renewal law, the language poet Bernstein has arrived from L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E to the Expanded Field of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, where applications of sound and syntax get renewed, signs and signifiers, objects and its properties coexist. As a result, a new horizon of possibilities for linguistic reference have been expanded without the complete disappearance of meanings and references. When the existing means of expressions become cliché monotonous and boring, Bernstein takes a leap for the expression by other means to find the other that forms a suitable means for carrying the soul of a new, and then engage the other means with the unknown space that reveals its face in creating meaning, because “Poetry’s social function is not to express but rather to explore the possibilities for expression”, as Bernstein’s Recalculating. It is the possibilities of other approaches, other expressions, other meanings⸺ the infinite possibilities of other.

In Unum Pluribus: Toward a More Perfect Invention —the opening essay of this chapter. Instead of the American national motto —one from many—Bernstein proposes In unum pluribus (in one many) and In pluribus unum (within many one) to celebrate the dialectical method of pluralism in the post-postmodern era with his innovative ever-emerging dialogic poetics. But this pluralism doesn’t deny the individualism, to echo Tagore:

At one pole of my being, I am one with sticks and stones. There I have to acknowledge the rule of universal law….But at the other pole of my being I am separate from all. There I have broken through the cordon of equality and stand alone as an individual. I am absolutely unique, I am I, I am incomparable….It is small in appearance but great in reality[8].

Tagore’s ‘individual I am’ realizes the freedom of harmony in the ‘infinite l am’because every individual with each one’s unfamiliar imaginations, distinct feelings, knowing and reasoning, in finite aspect in our multidimensional reality with its inevitable sequence of happenings, makes the sum total of the universe in infinite aspect. This is to echo Bernstein,

We should celebrate the pluralities even within the ‘purest’ of ourselves, because none of us is anything other than plural’ (PP:200).

It is, indeed, in resonance to Upaniṣadic mantra: Santam, Sivam, Advaitam, as Tagore called it — ‘the Peaceful, in the heart of all conflicts; the Good, who is revealed through all losses and sufferings; the One, in all diversities of creation.’[9]

This conflict is the aesthetic quiver of Bernstein that he uses in his bent studies in the quest for the diversities that drives his pataquerical action for his continuous queer inquiry into hyperreality. It is a dialectical process, which leads his action through struggles against the prescribed norms and rules, against the standardization of language.

Bernstein’s journey for the diversities of creation emphasizes on the aversive process that moves not with a predefined goal, but a provisional one, and tries to destabilize the conventional standards of judgements by its own standards. Bernstein’s In unum pluribus is a journey not to move towards the most perfect object but to move Toward a More Perfect Invention (PP:3). It’s a process of more correct, in Emersonian sense of Experience, because our journey is a never-ending process, rather finding ourselves on Emersonian stairs: ‘there are stairs below us, which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight’[10]. It is to echo Ihab Hassan's Postmodern Turn from ‘Art Object/ Finished Work’ towards ‘Process/ Performance/ Happening’[11], in resonance with Bernstein—

It’s still process, not product. You still don’t know exactly where you are going to come out before you are finished. It’s a turning away from a preconceived beginning, middle, and end, a rejection of closure. (PP:259)

Bernstein professes the rejection of closure because poetry is not a final state of any ideal perfection, but a movement, a performance, a happening. It is an open-ended process, an activity of making and doing to replace the practice of preconception to open up the space of possibilities with simultaneous inclusiveness and openness.

Pitch

The second chapter “Pitch” is centered on Bernstein’s critical discourse on the work of seventeen numbers of poets and writers. The word pitch in Pitch of Poetry is not only to signify the sound of poetry but also the approach, the angle of view, in a sense to register the particular style of the work. His discourses are not explanation but an extension of their work. Discourse, originated from the Latin word discursus, is an action of running in different directions. Since every action has a counter action due to the dynamicity of the action-actor entity of a matter or subject, his discourses also include counter discourses to provide an alternative point of view. He identifies Wittgenstein’s Philosophy of Psychology ⸺duck/rabbit⸺ as a ‘paradigmatic pataquerical figure’. Most of us do not see an object in its own right, but see as it appears in a figurative frame, which is actually a malady of suffering due to frame lock, an animalady in Bernstein’s term, to echo Wittgenstein’s ‘aspect blindness’, a malady of looking the world with a rigid materialistic view, not to see the inner soul beyond the physical periphery, not to see the philosophical and psychological aspects. It is a cultural malady of judging the value of a poem with fixed, predetermined, universally accepted standard, and hence stigmatizing as meaningless, feelingless poetry.

Due to this aspect blindness, we are stuck on a single interpretation of a poem. Instead Bernstein uses his third eye vision for acquiring a new point of view, a new dimension, to see the work of other poets differently by expansive consciousness that leads to a process of re-viewing old things with a new angle of observation with a new spectacle, to resonate with Prajñā (Sanskrit: ‘wisdom’), the higher power of intuition, in Buddhism.

In this chapter Bernstein reviewed the works of a wide range of authors— first-wave modernist Gertrude Stein: The Difference Is Spreading; second-wave modernist and objectivist Louis Zukofsky; postmodernist Charles Olson: A Note on “The Kingfishers”; German translator Paul Celan’s Folds and Veils; Barbara Guest: Composing Herself, the poet of New York School of Poet; Jackson Mac Low: Poetry as Art, the poet of New American Poetry; Robin Blaser’s Holy Forest, the American poet after second world war; third-wave modernist Robert Creeley: Hero of the Local; Larry Eigner’s Endless Song; John Ashbery: The Meandering Yangtze, the poet of New York School of Poet; Hannah Weiner’s Medium, the poet of New American Poetry; Haroldo de Campos: Thou Art Translated (Knot), the Portuguese poet of concrete poetry; Jerome Rothenberg: Double Preface, the father of Ethnopoetics; “And autumnstruck we would not hear the song”: On Thomas McEvilley, American poet and art critic; West Coast Language poet Leslie Scalapino’s Rhythmic Intensities; British poet Maggie O’Sullivan: Colliderings; Johanna Drucker: Figuring the Word, American author of Visual Poetry.

Any literary criticism is an evaluation process. Valuation is an estimation of the worth of something, which is always related to economy. Being in the heart of our capitalistic world, we always want to judge the economy of everything, even for poetry. Bernstein too doesn’t deny the economy of poetry, but it is negative economy, because ‘the economy of poetry is antipathetic to profit’ (PP:205). Though poetry has a negative price in the marketplace, but it creates a negative value, which is a different kind of economy —exchange economy— as coined by Bernstein.

What is exchange economy? It is an obtained currency from the muse of poetry, realized through critical discourse and counter discourse by the poets and readers. It is to create a model of ‘democratic social space’. It aims at a social practice where the constituted reality of the poet is reconstituted by the reader through critical reading and various means of poetic exchange like reviews, conversation, reading in a bar or website, reproduction by MP3 file, etcetera. Direct profit is not the purpose of this economy; rather, it tries to maximize exchange value by minimizing the losses from the cost of reproduction.

However, this critical reading demands not only intellect or knowledge but also imagination of the reader, the very basis of the Eastern intuitive philosophy. Factually, our mind itself creates its virtual realization and virtual imagination. This tendency converts our physical experiences into imaginary experiences, which becomes the fittest model of the world in our mind. This is where possibilities come into action with particular, incomparable, and unique imagination of each reader. This is also the very reason why the imaginary experiences of the consumer reader can’t be commodified in the poetic market. If the consumer is not passive but active to respond to poetry, the consumer himself reproduces not the products but the possibilities. Bernstein has named this responding process as ‘interenact’—to mean not only interact but also inter-enact to make it happen. Through his discourse on these seventeen poets Bernstein goes beyond the preconceived and prescribed norms or forms of poetry, and he engages himself in the interior of the poem with his own knowledge and imagination. That is how his Pitch creates infinite possibilities of other—other meanings, other frames, other values of poetry, with his unique process of (e)value-ation.

Echopoetics

The third chapter of Pitch of Poetry is Echopoetics, coined by Bernstein. it’s not the familiar Ecopoetics, but echo, the poetics of resonance, which Bernstein uncovers with his eleven interviews. Here Bernstein is fundamentally involved with language as a system of exchange and interweaves a network through which the intellectual wealth and process of poetics of the predecessor flows. The nodes of this network are the radiance of his experiences and spark of thoughts, by which he creates constellations (in Walter Benjamin's sense) through juxtaposition, not by comparing but by contrasting familiar concepts and ideas with his process of defamiliarization. This is where Bernstein’s echopoetics, not to echo in linear resonance, rather to find the material entanglement that marry the materiality of objects with aesthetic sensations with an essence of Pataquerical Imagination—

Echopoetics is the nonlinear resonance of one motif bouncing off another within an aesthetics of constellation. Even more, it’s the sensation of allusion in the absence of allusion. In other words, the echo I’m after is a blank: a shadow of an absent source. (PP:x)

When our mind is blank, it is not empty but a sense of emptiness, which is charged with the energy of our mind. It is like a quantum vacuum that possesses the seeds of uncertainty, an infinite potential well, the space of infinite possibilities. This is the endless silence of infinite, and the poet listens to this silence to receive the SPARK— Spontaneous Power Activated Resonance Kinetics (in Barin Ghosal’s term)[12]. This happens in a magic moment, a ‘less-thanconscious mental state’(PP:264), when the poet’s mental capacitance is just conducive enough to receive the spark to make the quark of poetry. Resonanceis related to vibration, ‘a kind of sound and rhythmic or musical patterning’. This resonance is an event, not an object but an occurrence, where associations are related to probabilities that cannot be expressed directly, but through imagination, and manifests itself through words. It’s a non-intellectual experience of reality in the intuitive mode of consciousness, the most sophisticated observational apparatus of Eastern philosophy to transform the objective reality to subjective reality.

It is the occasion, where the bare beauty of words invokes the soul of silence, embodied in human language. It is the celebration, where the words present their nude utterance to claim their place in the poem by referencing themselves. Their presence can be felt in their sounds and rhythms, charged with the shivering delight of the dark energy in the blank space of our mind.

This chapter includes Bernstein’s interviews with different magzine editors including— Contemporary Literature with Allison Cummings and Rocco Marinaccio, published in Contemporary Literature 41, no. 1 (Spring 2000); Musica Falsa: On Shadowtime with Eric Denut, published in Musica Falsa 20, Paris, 2004, on the occasion of the performance at the Festival D’Automne of Shadowtime, the Brian Ferneyhough opera in/around/about Walter Benjamin, for which Bernstein wrote the libretto; Foreign Literature Studies with Nie Zhenzhao, published in Foreign Literature Studies, Wuhan, China, 29, no.2, April 2007; The Humanities at Work with Yubraj Aryal, published in The Humanities at Work: International Exchange of Ideas in Aesthetics, Philosophy and Literature, ed. Yubraj Aryal, Kathmandu, Nepal: Sunlight, 2008; Bomb with Jay Sanders, published in Bomb 111, Spring 2010; Chicago Weekly with Daniel Benjamin, published in Chicago Weekly, February 18, 2010; FSG Poetry: All That Glitters Is Not Costume Jewelry with Alan Gilbert, published in The Best Words in Their Best Order, FSG Poetry, April 27, 2010; Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses:Editing as Com(op)posing with Manuel Brito, published in “Small Press Publishing: Absorbing New Forms, Circulating New Ideas,” ed. Manuel Brito, in Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses, no. 62, April 2011; Études anglaises: Poetry’s Clubfoot—Process, Faktura, Intensification with Penelope Galey-Sacks, published in Études anglaises 65, no. 2, 2012; Evening Will Come: Off-Key with Joshua Marie Wilkinson, published in Evening Will Come, no. 35, 2013; Wolf with Stephen Ross, published in Wolf 28, June 2013.

Bernstein’s echopoetic process is not to obliterate conventions but to swerve it from its past, its real existence, through constant convening and reconvening of language. It is the center of possibilities to create a space of greater freedom⸺ that is where the pataquericalism is. It is like a facsimile without any original— that is what writing is, in its reproducibility, as he writes—

Reality is usually a poor copy of the

imitation. The original is an echo of what is yet to be

…. I always

hear echoes and reverses

when I am listening to language. It’s

the field of my consciousness.[13]

Bent Studies

The fourth and the final chapter is Bent Studies. What it is? The promise of bent studies is to respond to the inventive but marginalized poetry, as Bernstein says,

‘The task of bent studies is to move beyond the “experimental” to the untried, necessary, newly forming, provisional, inventive’ (PP:297).

In nature's creative world, the complete or perfect creations are as much as the incomplete or imperfect one, the beauty of which is disregarded by most of the common viewers. But an artist can perceive the hints of meaning of those creations with their distinct thoughts, unfamiliar persona, and their own styles, which are not unordered but ordered differently. It is to mark a human creation into the immense diversity of nature's creative world. Bernstein explores the possibilities in language with his bent studies to respond with love to the bent, mute, marginalized, silenced, to celebrate the poetry that begins in disability. Like the video of Amanda Baggs’ In My Language[14], where autism is not an obstacle but a new experience of autistic consciousness that pushes the boundaries between intelligibility and sensation. It is to get rid of emotional rhapsody to redefine our sensitivity with difference where disorder is not weakness but in the sense of delicate, a pataquerical essence of the Bernsteinian bent studies. The ideology of bent studies is a quest for alternatives beside the existing one that engenders other positions, both complementary and oppositional. The counter-spirit of bent studies continuously explores alternative forms of aesthetic positions inside the dominated and dominating environment of the present poetic culture.

This chapter is constructed in a ballad form, which is named as The Pataquerical Imagination: Midrashic Antinomianism[15] and the Promise of Bent Studies. It is a fantasy of 140 fits. A fit, by definition, is a section of a poem or song; a canto. However, Bernstein’s song is not a carrier of words, tunes, musical measures, or tempos, but a conveyer of the poet’s own experiences, knowledge, and beliefs.

Bernstein’s pataquericalism is not just a poetics but also a philosophy of life, a leftist way to wrench freedom from authority. PATAQUERICS uses PATA(physics) (in Alfred Jarry’s term) to explore a QUE(e)R (in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s sense) I(nquiry)into system, into reality, into inner self, with a rhythmic oscillation between Yin and Yang in the space-time of our ever-changing world. Bernstein connects Wittgenstein’s ‘queer’ (Philosophical Investigations[16]) to astonishment that expresses the momentary excitement of our soul, which makes the expression of poem so odd, weird, bizarre, altered, or unexpected that it does not have an immediate intelligibility but triggers an excitement whose particularity can be expressed not by imitation of common language but by pataquerical imagination.

It is an action through inaction, to resonate with the quick pronunciation of Bosse-De-Nage’s pataphysical ‘ha ha’[17] until the phrase becomes confounded, random, odd, or queer. It is to push the absolute to uncertainty with the new age of absurdity. Bernstein’s pataquerics uses the science of exception of ’Pataphysics to perform the Faustrollian filtering of vision into the pataphysical world and to trigger the reader's mind with pataquerical imagination, because imagination is the key to create possibilities that may suggest a new way of life. It is a dream of a potential world to defy rationality, not with facial but with spatial freedom, to soar our soul in the infinite for photonizing the poetic rhythm with the pataquerical imagination.

The dramatis personae of this ballad are our legendary predecessors whose philosophies, poetics, and poetry have contributed to the construction of Bernstein's pataquericalism. They are Edgar Allan Poe, Alfred Jarry, William Blake, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Stéphane Mallarmé and Ralph Waldo Emerson of nineteenth century, and William Carlos Williams, Hart Crane, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Fanny Brice of twentieth century.

The Poetic Principle

Edgar Allan Poe’s iconic essay The Poetic Principle[18] is one of the most important fits of the fantasy to set the tomb of Poe as the birthplace of Bernstein’s pataquericalism. It is the founding document of the pataquerical line of American poetics. Poe defines the poetry of words as The Rhythmical Creation of Beauty. Beauty of a creation is the most surprising mystery because its utmost importance is not visible from the upper gloss, but it has its own ultimate value. Beauty, in fact, is an aesthetic sense, and a creation is an activity⸺ the play with joy, and the language of joy is beauty. However, when the pataquerical poets are savoring this beauty of poetry on a lukewarm tongue, the dark right corner of the official morality is sharpening their linguistic knife of truth and duty to slash their left tongue.

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty”[19] is an old but gold coin where the truth of the material world is transcended to the truth of the imaginary world, where emerald can be seen as green by the reflection of light through our consciousness. Again, Tagore says, “Beauty is truth's smile/ when she beholds her own face in a perfect mirror.”[20] Whether beauty is truth or truth’s smile, but surely it’s omnipresent and the poet listen to the rhythm of beauty, buzzing everywhere. The poet discovers the illusion, woven into the warp and woof of light and dark, a rhythmic oscillation between hope and despair, to acknowledge the paradox of reality, and personalizes its impersonal beauty. Only a poet can perceive the harmony by his sense of beauty, and finds his own principle of creation by his own sense of truth, because ‘Truth and falsehood mingle in life—and to what God builds man adds his own decoration. Only those were pure truths which were sung by the poet’[21], as revealed by Tagore. It is, indeed, in resonance with Bernstein, “Telling truth is a kind of lying since/ Every truth conceals both other truths and/ Plenty of falsehoods”[22]. Bernstein denies the existence of single truth rather explores its possibilities to activate the passive creative matrix that creates other truths by sudden opening of a new point of view.

Edgar Allan Poe preferred taste as the sole arbiter of poetry. And the origin of the taste is in our thought, which holds our concepts, beliefs, experiences, education, and knowledge. No thought without taste, no taste without thought. Taste and thought reflect or express each other to echo Tagore, “Taste of poetry needs to feel it but can’t be proved like theory…. Science is adjudged by its truth or falsity but poetry is adjudged by its taste”[23], to resonate with Bernstein, “For me writing poetry is all about making judgments, articulating tastes, especially (but not exclusively!) those which are not “officially” sanctioned” (PP:193)

Poe placed taste in between pure intellect and moral sense. Any principle, accepted and established principle in a particular society at a particular time is referred to as moral. But of morality in one set of circumstances cannot be that of another. In other words, morality resists invention. For innovative poetry Bernstein proposes that instead of single eye vision of Official Verse Culture (OVC, coined by Bernstein), third eye vision is required, which shifts our awareness from the rational mode to the intuitive mode of consciousness, originating from the dynamic interplay between the faculty of mind and faculty of intellect to create an intellectual imagination. It’s not irrational but aversive to logical understanding and way of reasoning, and much more than merely intellectual.

As Poe says, “Unless incidentally, it has no concern whatever either with Duty or with Truth”, poetry is not to mediate truth, then what must poetry do? The pataquerical Bernstein answers:

The task for poetry is not to translate itself into the language of social and linguistic norms but to question those norms and, indeed, to explore the ways they are used to discipline and contain dissent. Poetry offers not a moral compass but an aesthetic probe. And it can provide a radical alternative to the outcome-driven thinking. (PP:79)

Bernstein rejects the accepted standard of normativity to renew it with his Pataqueronormativities (PP:326), charged by the pataquerical imagination. It is to profess his poetics not with the norm of virtuous sentiment but with the patanorm of poetic truthfulness, as he says, “The poetics here is ethical, not moral: dialogic and situational rather than fixed and rule-bound.” (PP:3)

Only this and nothing more

Poe’s better-known pronouncement “only this and nothing more” from his poem “Raven” has taken the center stage of Bernstein’s pataquerical fantasy to play the rhythm of the noise of silence. The phrase only this and nothing more is one of the most important fits of the fantasy, where Mallarmé’s Throw of the Dice is charged with the shivering delight in Williams’ blank,to echo ‘nothing but the blank’[24] for the Poe-tics of JAMAIS with a senseof rhythm of Mallarmé’s never.

The Poetic Principle of shivering delight is the momentary rhythm of the music of a poem that tugs at our heartstring like a striking chord of ‘an earthly harp’ in Poe’s words, with a ‘meaningless mirth like twinkles of light on the ripples/ Strike in chords from your harp fitful momentary rhythms’[25], in Tagore’s words. It’s like the ‘rhythmic suspense of the disaster, to bury itself in the original foam’[26]in Mallarmé’s words, for the creation of supernal beauty where Mallarmé’s throw of the Dice never abolishes chance.

Nothing but the blank, the dark, the world of unknown. It is Kṛiṣṇa, the black, Pitch of Poetry. It is ‘presence in absence, the pataquerical sublime’, where the inherent music of nude words in a poem could be heard. It is to sing the song of Dickinsonian nothing with the tone of Bernsteinian blank⸺ ‘nothing in the sense of not one thing: variants around a blank center’(PP:278). It is the noise of silence, which sparks around the blank center in the dark silence of mind. It is the abyss of nothing,in which all realities dissolve, where Mallarmé’s COMME SI⸺ as if⸺ signaling with the noise of silence towards Poe-tics⸺ only this and nothing more.

Anti–bachelor machines

Charles Bernstein, the born punster, takes us through the verbal punning of language by his anti-bachelor machines, an apparatus for the constructional process of his pataquerics. It is a Bernsteinian attempt to alchemize Duchamp’s bachelor machines by transforming Large Glass’s[27] visual-pun to verbal-pun on his quest for the expression and figuration in poetry.

The scientific root of Bernstein’s anti-bachelor machines lies in the physics of the abstract art of Duchamp’s Large Glass through an interplay with Jarryan ’Pataphysics, which provides Bernsteinian ‘imperceivable solutions to opaque problems’ (PP:171), because the pataphysical perception is the key to reality by possible expansion of the laws of physics and chemistry with flourishing imaginations. The philosophical root of his anti-bachelor machines is linked to Jean-Jacques Lecercle’s délire (delirium) where sense emerges out of nonsense, because the meaning of words in a poem plays an Alice-in-Wonderland venture to say, ‘When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less’[28], like nonsensical riddles of koan in Zen, like paradoxical anecdotes in Taoism, like “nonsense” and “gibberish”— two primary pataquericals.

The visual impulse through the transparency of Duchamp’s large glass is accompanied by the irony of an opaque and amorphous literary text⸺ The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. Duchamp colored his Green Box to convey the marginal notes to unveil the Bride’s veil with a positive ironism⸺ ‘Ironism of affirmation: differences from negative ironism dependent solely on laughter’, as Duchamp said. This is where the Bernsteinian anti-bachelor machine⸺ “Recantorium: A Bachelor Machine after Duchamp after Kafka”:

I was in error, I apologize, I recant. I altogether abandon the false doctrine of Midrashic Antinomianism and Bent Studies, which I have promulgated in writings, lectures, and teaching, with its base and cowardly insistence on ethical, dialogic, and situational values rather than fixed and immutable moral laws.[29]

Duchamp’s Large Glass for eyes and Green Box text for ears become complementary to each other to resonate with Bernstein’s poetics, where the visibility of language and scientific audibility of the words presents themselves with pataquerical imagination, because “the wildness of the imagination is the greatest guarantor not only of freedom but also of reality” (PP:212).

Irremediation

This is fit of the fantasy to present Bernstein’s double negation process for judging the aesthetic power of the poem with Wittgensteinian affirmation— ‘double negative is an affirmative…. the negation-sign occasioned our doing something’ (§549). Hart Crane’s long poem ‘The Bridge’ takes the center stage here. Moralist critics at one end and patacritics at the other end are playing the ballad to 'pick up' the poem by judging its failure or success. Bernstein applies Poe’s 'flashpoint aesthetics' with his negation mantra to arrive at Irremediation.

The failure of The Bridge, marked by the moralist critics, is re-valued by R.P. Blackmur as ‘splendid failure’[30]. But the patacritic Bernstein applies his first negation by his literary in(ter)vention in the word splendid and the second negation by his resistance to connect any poem with failure. He calls ‘splendid failure’ as animalady and takes his turning by connecting it to the Latin prefix⸺ir (=not) to perform the double action of negation. To affirm its success by negating the failure, Bernstein has used resplendent (=splendid) with prefix ‘ir’ for a negation. It is to mark The Bridge as ‘irresplendent success’ to blast the demarcation, presented by the moralist critic.

This negation process of Bernstein becomes the root for naming of the fit as irremediation=irremedi(able)+(immedi)ation. On one hand, it registers the irremediable animalady of the ‘splendid failure’ of The Bridge in Bernsteinian pataquerical zone, and on the other hand, it registers the sensational immediacy with sexual transiency to echo flashpoint aesthetics of Poe. The value of a poem lies in the ratio of the aesthetic fire to flame our soul for its elevation, as Poe-tics: ‘brief and indeterminate glimpses’, where every action of excitement is transient, a flash of moment, a psychic experience, that render the relational angles with the joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain. Whole is always manifested in its parts, which are polymorphic, multiform, but moralist sees the parts only as divisions, separations and hence demands a unified whole from The Bridge. In reality, every part carries the inner essence of a whole, the unbound, which cannot be seen by eyes, but can be perceived by meditation of a sage, by intuition of a scientist or a poet. This is where the philosophy of Bernstein’s pataquericalism that raises the value of a poem by (e)value-ation to make it invaluable.

Anaesthestics

Anaesthestics is one of the important fits of his pataquerical fantasy to associate his aesthetics with the process of anesthesia:

Anaesthestics = anaesthes(ia) + (aesthe)tics.

The medical process of anesthesia disconnects the brain from the body to make someone unconscious. But Bernstein’s anaesthestics is an approach of aesthetics with the process of anesthesia to make unconscious not by disconnection but by aversion from the officially accepted aesthetics with the rhythm of his rejection of beauty and emotion.

But how is it possible while both beauty and emotion lies in the very root of poetry. Actually, the conflict lies in our inability to comprehend the difference between emotion and passion for poetry. Passion is the fuel of poetry that forces us to do the action for exploring the experience of beauty. But emotion is a state of mind, a mental attachment to the outcome of our action. If one becomes submissive to the senses, emotion makes its e-motion to enter into the territory of sentimentalism. Bernstein’s Anaesthestics is an aesthetic process that not only anesthetizes the socially accepted beauty but also uproots that sense of beauty.

Bernstein’s rejection is not to denounce emotion or beauty but to announce for seeking a new beauty, new definition of emotion, not emotion, but sensation, not to measure its effect but to affect in psychological sense. In other words, it is an alternative approach to experience the beauty, which does not anesthetize our consciousness. It is neither limited by the pressure of any authority nor tied by the chain of dogmatic morality. Such experiences adorned the beauty with uniqueness and diversity of the individual imagination. This process enables one to dream of a new beauty, where the possibilities of beauty can take a flight.

The Human Abstract

This is another crucial fit of the fantasy where Charles Bernstein presents his own version of William Blake’s poem “The Human Abstract”[31] to draw the image of the modern reified human being, making it into an idea, in opposition to the human concrete, the human particular.

About two centuries ago, William Blake, the visionary poet, could feel the real picture of the future human beings. He realized how human beings, detached from their original form, transform themselves to a particular form, which is their own abstract for their own existence, under the veil of the universal humane sentiment. Through millions of years of evolution, Homo sapiens have reached the present abstract form of human, a marvelous square-cut finish of spirit. They are growing the Blakean tree with pity, where they “sits down with holy fears,/ And waters the ground with tears”. But why this holy fear, how the Divine Image becomes Human Abstract?

'I', the sense of self, the other name of spirit or soul, is the central command over our mind, information agency and counter-action agency of our body. Our thinking world around this spirit is named as spiritual world, which includes philosophies, poetry, literature, science, etcetera. That is where the study of this spiritual world becomes science of all sciences. When this thinking world possesses our spirit, we feel joy or sorrow. The primitive philosophers named this spiritual feeling as God. In other words, the self-realization of our soul is God, to echo Know thyself. The primitive men naturally felt their own spiritual qualities through their experiences in this material world and imagined as God, which was nothing but their own image, Blakean Divine Image, purely imaginary, bound neither by doctrine, nor by dogma.

But through the pro-gress of the human civilization, under the authority of the religious institutions, human being gradually dys-gress from his Divine Image to Human Abstract. Fabrications of the so-called God is elaborately woven for the benefit of religious authority to “spreads the dismal shade/ of Mystery over his head”. Mystery is a puzzle here, kept secret, remains unexplained and unknown to human beings that forces them to understand that God is unknowable. The self-appointed representatives of this God in the civilized society becomes salvation peddler who used to make a deal with the humble human being in the market of God's oikonomia to commodify their spiritual yearnings. You have to pay a gold coin in your way to salvation. You have to obey God to get pity as God’s blessings. Bernstein calls this as Blakean pity, which is ‘cruelty’ that ‘knits a snare,/ And spreads his baits with care’, from which the humility originates.

But humility is not humble but humilis, the Latin word, literally means low─ human beings spend their life under the care of God as the so-called religion taught them, and hence feel low, insignificant in front of God that creates their holy fear. It’s nothing but a lack of confidence on their own ability. They are not able to negate the negatives and not able to realize human divinity, the God whose kingdom of heaven is within us. Hence the present Human abstract is going on growing the Blakean tree that “bears the fruit of Deceit, / Ruddy and sweet to eat.”

Bernstein calls this malady of the human abstract as ‘animalady’, coined by him, ‘the human malady of being and resisting being animal’ (PP:304). He compared the humane poetry of the human abstract with Blakean ‘pity’, which act as Derridean pharmakon for this animalady. Pharmakon has double sense: acting as a drug, the medicine for the ‘poor’, and poison in scapegoating, just like our language⸺ truthfulness (remedy) and deception (malady).

Poetry is a performance of language with its materiality by sensuous embodiment of words in a poem. The dominant politics of language of the OVC rejects the materiality of poetry and reified poetry as speech or sentimentalized as orality and grows the Blakean parasite in the name of humane poetry under their law of purification. The reification of the poetic materiality could have been a cause of celebration, but OVC uses it as a reason of repression, and stigmatizes those who are outside of their containment zone as unofficial, unauthorized. Bernstein explores the possibilities in language with his bent studies to respond with love to those marginalized who are marked as obsolete/abandoned/unofficial by official verse culture. This is where his own version of Blake's poem under the same title "The Human Abstract"—

The shortest distance

between two points is love. [32]

[1] Recalculating by Charles Bernstein, University of Chicago Press, 2013, p:90

[2] Śrīmadbhagavadgītā (Sanskrit: ‘the song of God’)—Indian Sanskrit scripture where verses are the dialogic discourse between prince Arjuna and his guide and charioteer Krishna in the battlefield of Kurukshetra. It’s a part of Mahabharata, the Ancient Indian epic. Source: www.gitasupersite.iitk

[3] Fireflies by Rabindranath Tagore, originally published in 1928, Niyogi Books, Delhi, India, 2012.

[4]A Pitch of Philosophy: Autobiographical Exercises by Stanley Cavell, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1994.

[5] “Too Philosophical for a Poet”: A Conversation with Charles Bernstein, an interview by drew David King; published in boundary 2 (2017) 44 (3): 17–57. read.dukeupress.edu/boundary-2/article/44/3/17/129292/Too-Philosophical-for-a-Poet-A-Conversation-with.

[6] “The contextualizing capacity of the writing itself”, an Interview of Bruce Andrews with Dennis Büscher-Ulbrich, https://jacket2.org/interviews/contextualizing-capacity-writing-itself.

[7] The L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Book by Charles Bernstein and Bruce Andrews, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. 1984. The paragraph is quoted by Bernstein in Pitch of Poetry, p-60.

[8] Essay “The Problem of Self” by Rabindranath Tagore, included in his essay collection Sadhana (The Realization of Life), 1913. Source: The Complete Works of Rabindranath Tagore, General Press, New Delhi, India, 2017.

[9] Lecture: “The Center of Indian Culture” by Rabindranath Tagore, delivered in Madras on February 9, 1919. Source: The Complete Works of Rabindranath Tagore.

[10]Essay:Experience by Ralph Waldo Emerson, collected in Essays:Second Series, 1844, emersoncentral.com/texts/essays-second-series.

[11] Essay: “Toward a Concept of Postmodernism” from The Postmodern Turn: Essays in Postmodern Theory and Culture by Ihab Hassan, Ohio State University Press, 1987.

[12] Otichetonar Kotha (On Expansive Consciousness) by Barin Ghosal, Kaurab Publication, Jamshedpur, 1996.

[13] Near/Miss by Charles Bernstein, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2018, p-79.

[14] Video: In My Language by Amanda Baggs, www.youtube.com/watch?v=JnylM1hI2jc.

[15] Midrashic─ Hebrew miḏrāš─ an ancient commentary on part of the Hebrew scriptures, attached to the biblical text. Antinomianism- Etymology < Greek ἀντί against νόμος law, an ism to believe that they are not bound by moral law, instead rejects laws or legalism and argues against moral, religious or social norms. The phrase Midrashic Antinomianism is coined by Charles Bernstein.

[16]Philosophical Investigations by Ludwig Wittgenstein, tr. by G. E. M. Anscombe, ed. G. E. M. Anscombe, R. Rhees, G. H. Von Wright, Basil Blackwell Ltd, Oxford, 1958.

[17] Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician by Alfred Jarry, 1911, translated by Symon Watson Taylor, introduced by Roger Shattuck, published by Exact Change, 1996.

[18] Essay: ‘The Poetic Principle’ by Edgar Allan Poe, 1850. Source: https://www.eapoe.org. accessed on 15-8-2021

[19] Poem “Ode on a Grecian Urn” from Lamia, Isabella, the Eve of St Agnes and Other Poemsby John Keats, 1820, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44477/ode-on-a-grecian-urn.

[20] Fireflies by Rabindranath Tagore, originally published in 1928, https://tagoreweb.in/Verses/fireflies-200/beauty-is-7741.

[21] Short story: “Joy Parajay” (The Victory) by Rabindranath Tagore, 1892, source: The Complete Works of Rabindranath Tagore.

[22] Topsy-Turvy by Charles Bernstein, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2021, p-16.

[23] Sahitya by Rabindranath Tagore, Viswabharati, 1417, p-230

[24] Poem: “Paterson” by William Carlos Williams, Collected Poems, vol. 1, edited by A. Walton Litz and Christopher MacGowan, New York: New Directions, 1986.

[25] The Gardener by Rabindranath Tagore, 1913, source: The Complete Works of Rabindranath Tagore

[26]Un coup de Dés & other poems by Stéphane Mallarmé, 1897, tr. A. S. Kline. Source: www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/French/Mallarmehome.php

[27] Painting: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even by Marcel Duchamp, which is also called The Large Glass. And The Green Box is the notations and diagrams in preparation for the painting, collected in The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson, New York: Da Capo Press, 1973.

[28] Through The Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll, 1872, New York: Dodge Publishing company, 1909.

[29] Attack of the Difficult Poems: Essays and Inventions by Charles Bernstein,University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2011, p-280.

[30] Samuel R. Delany, “Atlantis Rose: Some Notes on Hart Crane,” in Longer Views: Extended Essays (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1996). Delany discusses Blackmur’s essay ‘Notes on a Text of Hart Crane,’ on pp. 192–91.

[31]Poem “The Human Abstract” from Songs of Experience by Willum Blake, 1794, www.gutenberg.org/ebooks

[32] Poem: “The Human Abstract” collected in With Strings by Charles Bernstein, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p-35

••••

J2 links to Bandyopadhyay on Bernstein below, but see also:

Runa Bandyopadhyay (West Bengal), conversation, Kitaab, March 8, 2019 (excerpted by Harriet)

On Utopia in Susan Bee, Regis Bonviciono, and Bernstein: Aparjan Feb. 2021 (W. Bengal), in Bengali; see English summary