Jennifer Bartlett in conversation with Jane Joritz-Nakagawa

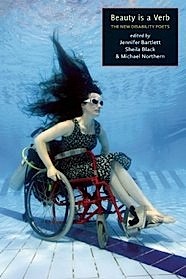

Jane Joritz-Nakagawa: Jennifer, I’d like to start by discussing the anthology you co-edited, Beauty is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability. In the preface you explain that a purpose of the anthology was to present non-mainstream views of disability while offering a considerable range of stylistic diversity in poetry by disabled poets, mostly poets with a visible disability. Since the anthology was a collaboration I wanted to ask you what you learned through the process — what benefits did you receive and what hurtles did you need to overcome? What did you learn both from the process of collaboration and from the project as a whole? Also, how would you evaluate the result — do you feel you achieved your aims? What reactions have you received from readers who identify as disabled and from others who don’t? (This is a bunch of questions that we could discuss either separately or all together, depending on how you wish to answer them!)

Jennifer Bartlett: I’ll begin with the last questions and move backward. I definitely feel the anthology achieved our aims. We were able to put something into the world that we are proud of, and the book met our objective, which was to create an anthology that both spoke to disability politics and included excellent poetry. We, of course, also had the hope that it be widely read and taught. We have been lucky to have that happen as well.

The feedback I have gotten has been positive. In listening to people’s reading experience, I learned that Laura Hershey’s essay was perhaps the most crucial in the collection; a number of readers have told me Hershey’s story had a profound effect on their thinking.

I had some earlier experience working on an anthology. My father, Lee Bartlett, is a retired professor from the University of New Mexico, as well as a critic and poet. He co-edited the poetry anthology In Company: An Anthology of Poets in New Mexico After 1960. Assisting him with this project gave me the rudimentary skills needed to begin to conceptualize a project of my own. My father’s advice in writing the introduction, in particular, was seminal. He asked questions such as why not include mental and cognitive disabilities? What place does alcoholism have in the conceptualization of disability? What about HIV/AIDS? Cancer? Writing the introduction together, we were able to avoid having to later defend our choices. My father noted, “You just ‘point’ in the introduction.” Poetry for me is somewhat of a “family business.”

Collaborating on Beauty is a Verb was one of the most difficult and enriching things I have done as a poet and editor. I am a very controlling person, and I have strong ideas about what makes a good poem. Going into the project, I knew very little about disability poetics. My editorial part was to gather work from poets I know in my own community, poets such as Norma Cole, Larry Eigner, and Bernadette Mayer, whose work I love, but who also happen to have disabilities. Poets such as John Lee Clark, Jim Ferris, and Laura Hershey were not on my radar at that time. I am grateful, largely to Michael Northen, to have been introduced to and come to appreciate these poets’ works. I am also grateful to have worked with people with a variety of disabilities in a way that I hadn’t before. This taught me new ways of communicating, understanding, and thinking about the body. The primary obstacle I had to overcome was my own prejudice about what makes a good poem. Ironically, I am more open-minded in terms of style than most poets. Yet, I still have to grapple with my own judgments when it comes to deciding who — and who should not — be included. When you have more than one editor working on a project, this it something debated constantly: who and what to include. It was good for me to have to back down at points and learn from others.

The only regret I have about the anthology is that we did not include Adrienne Rich and a few other poets. At the time, I was unaware of how important this might be. I think Sheila Black contacted her estate and the prospect was too expensive. I would also like to have made a case, also influenced by my father’s ideas, for the work of Olson, Creeley, and Duncan through the lens of disability and Projective Verse.

JJN: An ambitious project and as you know I’ve read the anthology, which I first heard of on an e-list, with much enthusiasm which led to me also finding your poetry, which we will discuss in a minute, and to my proposing this interview! The Hershey essay is great but as I like all of the essays . . . something (many things!) about Cynthia Hogue’s (who I’ve had the pleasure of twice interviewing via email, though we’ve never met in person) resonates quite deeply with me, however, and I think also Brian Teare’s, although I share a condition in common with a different contributor. Both Hershey and Hogue mention Adrienne Rich in their essays so Rich was in a sense included in the anthology! Nothing to feel bad about — in my opinion this anthology is an amazing achievement — you successfully, I believe, bring together various poets working in various styles yet it coalesces — there is diversity on many levels, in writing styles, gender, age, in terms of disabilities — some rare, some more common such as forms of arthritis. I think it’s very good you included some familiar to most people conditions like arthritis because it widens the net and creates broader connections (of disability as something more ordinary and common), and there is of course a diversity of perspectives on disability, diversity in terms of sexual orientation and ways of thinking about diversity, diverse backgrounds and eras, some poets no longer with us, etc. And then visible versus invisible disability (though within both of these of course lie the possibility of the visible being invisible in certain circumstances and the invisible being visible at least to some people some of the time so these terms are a little imprecise but — I was glad you included also so-called invisible disability because that includes many people). In any case I can easily see this book as part of a course on poetry and multiculturalism or poetry and diversity but also very possibly outside a literary course in a multidisciplinary course having some relation to disability or diversity (have you heard of such course adoption?). I think some people who are not poets or very familiar with poetry would be interested in the book (have you found that to be true?) and because it contains essays the essays could also help introduce poetry to non-poets. I learned a lot myself in terms of for example John Lee Clark’s discussion of ASL poetry.

JJN: An ambitious project and as you know I’ve read the anthology, which I first heard of on an e-list, with much enthusiasm which led to me also finding your poetry, which we will discuss in a minute, and to my proposing this interview! The Hershey essay is great but as I like all of the essays . . . something (many things!) about Cynthia Hogue’s (who I’ve had the pleasure of twice interviewing via email, though we’ve never met in person) resonates quite deeply with me, however, and I think also Brian Teare’s, although I share a condition in common with a different contributor. Both Hershey and Hogue mention Adrienne Rich in their essays so Rich was in a sense included in the anthology! Nothing to feel bad about — in my opinion this anthology is an amazing achievement — you successfully, I believe, bring together various poets working in various styles yet it coalesces — there is diversity on many levels, in writing styles, gender, age, in terms of disabilities — some rare, some more common such as forms of arthritis. I think it’s very good you included some familiar to most people conditions like arthritis because it widens the net and creates broader connections (of disability as something more ordinary and common), and there is of course a diversity of perspectives on disability, diversity in terms of sexual orientation and ways of thinking about diversity, diverse backgrounds and eras, some poets no longer with us, etc. And then visible versus invisible disability (though within both of these of course lie the possibility of the visible being invisible in certain circumstances and the invisible being visible at least to some people some of the time so these terms are a little imprecise but — I was glad you included also so-called invisible disability because that includes many people). In any case I can easily see this book as part of a course on poetry and multiculturalism or poetry and diversity but also very possibly outside a literary course in a multidisciplinary course having some relation to disability or diversity (have you heard of such course adoption?). I think some people who are not poets or very familiar with poetry would be interested in the book (have you found that to be true?) and because it contains essays the essays could also help introduce poetry to non-poets. I learned a lot myself in terms of for example John Lee Clark’s discussion of ASL poetry.

I ordered a copy incidentally for my non-poet, but readerly, elderly father on his recent birthday (I haven’t gotten his feedback yet but my mother has been sick and in the hospital so he’s not maybe had a chance to read it yet) and also mentioned it in a column I write for a local women’s group because I think there will be many (non-poet) women interested in it. In any case, a remarkable achievement, kudos to you.

Like you I have diverse tastes in poetry — though there are poems I don’t like for example if predictable or overly sentimental, if there isn’t sufficient thought in the poem — I can understand and imagine the challenges of working with co-editors but also the benefits.

I’ve been reading Susan Wendell’s The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability (Routledge, 1996) and one of the many points she makes is how disabled people (I am following your use of this term; while living in Japan I heard of the English term “differently-abled” which appealed to me from afar but don’t know the history of the term — Japanese language for talking about persons with disabilities has evolved also, e.g. the equivalent of “person with a disability” has replaced to a large extent “disabled person” in Japanese) have special knowledge of the body that is useful for everybody. I feel this is very apparent in your anthology. I also was led to consider many issues about identity and how it manifests in poetry while reading Beauty is a Verb.

Can you tell about The Larry Eigner Project?

JB: Jane, thank you for all your perceptive comments. I love the comment about special knowledge. We did take care to make the anthology as diverse as possible, not only in terms of disability, but race and sexual orientation. Women greatly outnumber the men.

The project, in fact, was ambitious. I can only take a small part of the credit for that. Sheila Black and Michael Northen both brought wonderful poets and ideas to the project. Black secured our publisher, Cinco Puntos. All the folks at the press were wonderful to work with, as was our designer, Jeff Bryant.

Yes, the book has garnered attention as a teaching tool (and otherwise) outside the poetry world. My son and I, in fact, recently traveled to Brown University to give a talk to an undergraduate class of future doctors and medical workers. I have heard that such courses are utilizing the book, as well as disability studies courses. In fact, non-poets have embraced the work a little more than the poetry community simply because disability poetics is not a recognized “school.”

Regarding Larry Eigner, I am glad you called it the ‘project’ because that is an accurate word. Interestingly, Eigner had ties to Japan, where you now live, because, as you know, his primary friend and colleague in poetry was Cid Corman.

I began writing on Eigner four years ago. I was done with Beauty is a Verb and considering leaving my adjunct position teaching Freshman Composition. I have always loved biographies, and I had considered for years writing a biography of Muriel Rukeyser. I had even spoken with Jane Freeman from Paris Press about that idea, but never went ahead.

A friend who loved Eigner’s work urged me to go on with the project and in fall 2011, Charles Bernstein introduced me to Robert Grenier, Eigner’s caregiver for many years. Grenier and I instantly hit it off. This was the first green light for the project. The following summer I traveled to California and spent the weekend with Grenier in Bolinas. I met the Eigners (Richard and Beverly), and Jack and Adele Foley, and spent one day at Stanford in the archive. I have to say, I dove into the project not knowing much about Eigner and what to expect. The warmth and support of people in Berkeley was an impetus for continuing the project.

Then, I began doing research. I taught myself how to use a finding aid, the rules for looking at archival material, and how to do research. I also had the advice of my father. I spent hours in the NYPL Berg Collection, which I found had a number of “secret” Eigner letters. I went through every single copy of Black Mountain Review and Origin. I tracked down every one of Eigner’s books and began to read books that he read. In essence, I gave myself a Ph.D. without any mentoring or financial support. As I went along, I learnt how to read Eigner’s letters and decode his references, typos, and generally quirky writing. I learnt basically the entire history of Black Mountain Poetics, Cid Corman, and Origin magazine. At this point, I have a potential publisher with the University of Alabama Press, through Bernstein and Hugh Lazer, and 200 pages of text.

Then, I began doing research. I taught myself how to use a finding aid, the rules for looking at archival material, and how to do research. I also had the advice of my father. I spent hours in the NYPL Berg Collection, which I found had a number of “secret” Eigner letters. I went through every single copy of Black Mountain Review and Origin. I tracked down every one of Eigner’s books and began to read books that he read. In essence, I gave myself a Ph.D. without any mentoring or financial support. As I went along, I learnt how to read Eigner’s letters and decode his references, typos, and generally quirky writing. I learnt basically the entire history of Black Mountain Poetics, Cid Corman, and Origin magazine. At this point, I have a potential publisher with the University of Alabama Press, through Bernstein and Hugh Lazer, and 200 pages of text.

But the “project” has gone far beyond just the biography. I have begun to work with others on editing some of Eigner’s letters for publication. George Hart and I have a selection of these letters forthcoming this summer in Poetry. After gaining their trust, the Eigner family allowed me to decide which archive will have his final books and manuscripts. I was allowed to use them for my research before sending them to the Dodd Research Library at UConn. I am not the only one working on bringing Eigner’s work to light. Grenier and Curtis Fayville have edited a Selected Poems also forthcoming (under review at University of Alabam Press), Stephanie Anderson has edited letters forthcoming in Chicago Review, and my dear friend Andrew Rippeon is editing a book of letters from Eigner to Jonathon Williams.

Eigner is a great poet, who like many has been marginalized, and bringing the work of any great poet back into the public consciousness is a worthwhile endeavor. Due to his severe cerebral palsy, there has been quite a bit of misinformation about Eigner’s life and work. My project intends to set the record straight. Since Eigner didn’t have much of a public life until after the age 50, all of the public/poetic/intellectual life occurs in letters — letters that no one has, yet, read. To tell the true story of Eigner’s life, for me, is to tell the story of many people with disabilities. Since Eigner was, for a time, very influenced by Creeley and Olson, and since Robert Duncan typed hundreds of his manuscripts, Eigner’s life is also the story of their lives.

JJN: This is fantastic! By the way I would love to create a poetry course using Beauty is a Verb! The stylistic diversity in terms of the poetry is a big plus for, for example, perhaps a more introductory level course in poetry and diversity (where a goal could be to try to introduce students to various styles of poetry). Most anthologies and textbooks I have seen tend to be relatively mono-cultural and mono-stylistic (and thus can require a lot of supplementation when that’s unwanted).

I’m amazed at your energetic efforts on behalf of the Larry Eigner project! You can see the influence of Japanese traditional poetry in Eigner’s work, e.g. a way of economically using concrete imagery to create something abstract. I love the musicality in his work. In a review of two of my poetry books my poetry was compared to his! which I took of course as a gigantic compliment, though I think it’s the book I put out in 2013 (subsequent to that review, titled FLUX; review by Pam Brown recently appeared, which contains the most Eigner-esque portions — not that I was consciously trying to imitate Eigner or anybody else exactly when writing that or any book, but, you know, everything we encounter can influence our work, gets stored in our brains — sometimes I don’t see those connections until long after I’ve finished something — if at all)!

In any case, congrats to you — the Larry Eigner Project will be something for everybody to look forward to!

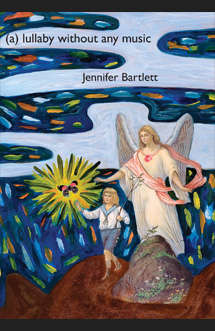

I’d like to turn to your poetry now, Jennifer. You’ve two books, Derivative of the Moving Image and (a) lullaby without any music. You said above that you have broad tastes in poetry, which I think is reflected in your work in that your poetry here is both lyrical (in various senses of the word) and experimental. I’m interested in the overall framework of both books and how you arrived at them. I’m also wondering — there are similarities and differences between these two books — how would you characterize those yourself? What changed for you between books?

JB: My books are heavily influenced by my reading, education in poetry, and lifestyle at any given time. When I wrote the first book, I was a (very) young writer. All of the poems in the collection were written by the time I was 28 years old; many of them were written in my early 20s. It might be obvious from the line length that I was reading (and beginning to be influenced by) Jorie Graham and Allen Ginsberg. I was also working at a museum and dating a filmmaker, so there is a lot of testimony to visual art in this book. Many of the poems are so-called “prose” poems. I wrote like this simply because I knew I wanted to say something, but I did not know how to make a line yet.

As I wrote my second book, my life and reading habits began to change. I started to read a huge variety of poetry. I have always been proud of the fact that I try not to be prejudiced about form and “schools.” I love Charles Bernstein and Robert Grenier, but I also love Marie Howe and Mary Oliver. I also love Eliot and Rukeyser and Stein and Olson.

Later, my own poetry became focused more on grappling with the difficulties of domesticity: being in a long-term marriage and raising a child. My lines became shorter and more direct. But, I would just write from beginning to end with very little editing or rearrangement. So, these “books” just appear. I used to feel tremendous guilt and feel like I was a loser or lazy if I didn’t write a certain number of poems in a week. It’s like that line in the song Lou Reed says Andy Warhol told him — “You only wrote X songs; you should have written Y. The truth was I hadn’t written anything!” But, I learned that my brain didn’t work that way. Poems are something I have to wait for. I am lucky to have other projects, so my writing has a place to go and I feel “at work.” I just don’t put so much pressure on myself anymore — to publish, to get awards, some poets really want to win. I wanted to be popular! But, if I continued to focus on that, I would be really unhappy. The best two pieces of advice about poetry I ever received were “Poetry is not a horse race” (Nathanial Tarn) and “You only want to write as many poems as you have to” (Lisa Jarnot).

Later, my own poetry became focused more on grappling with the difficulties of domesticity: being in a long-term marriage and raising a child. My lines became shorter and more direct. But, I would just write from beginning to end with very little editing or rearrangement. So, these “books” just appear. I used to feel tremendous guilt and feel like I was a loser or lazy if I didn’t write a certain number of poems in a week. It’s like that line in the song Lou Reed says Andy Warhol told him — “You only wrote X songs; you should have written Y. The truth was I hadn’t written anything!” But, I learned that my brain didn’t work that way. Poems are something I have to wait for. I am lucky to have other projects, so my writing has a place to go and I feel “at work.” I just don’t put so much pressure on myself anymore — to publish, to get awards, some poets really want to win. I wanted to be popular! But, if I continued to focus on that, I would be really unhappy. The best two pieces of advice about poetry I ever received were “Poetry is not a horse race” (Nathanial Tarn) and “You only want to write as many poems as you have to” (Lisa Jarnot).

JJN: I write when I feel like it and when I have the time, which however is fairly often (even when I was busy with a burnout job I managed to find time to write but I can easily get poetry work done even in stolen moments I think). I never think about rewards other than the reward of writing (for me sometimes I’m not sure there are any other than that!), though I do think that I want to share what I’ve written with somebody after, poetry being a form of communication after all, as a future reward. As far as awards, I think the best work often doesn’t get awards and may be unpopular so I don’t think of not getting an award as something bad;-). I suppose the idea of awards is a bit mainstream to me and that I tend to associate them with mainstream writing. Also awards seem hierarchical to me and thus patriarchal/phallocentric (as a teacher for many years I always disliked the idea of ranking students or singling some out among others etc, which is silly anyway since all students have different talents). Yet of course if one gets one, why not use it to one’s advantage . . . I mentioned myself a poetry award I received (though I entered no contest) in the acknowledgments page in my last year’s book FLUX despite the feelings I’ve just described. I think quality matters more than quantity. To be able to leave some good work behind (whether a little or a lot), that’s a reasonable goal I think.

You mention visual art; the book I’m working on now (titled distant landscapes) has a lot to do with visual art by Japanese artists, though there are other influences of course too.

I think both of your books show a lot of skill, including the earlier one that you wrote when young. Derivative of the Moving Image is divided into five sections; I was wondering how this came about — did you write the sections individually as sections? (a) lullaby without any music (which I think could also be aptly called music without any lullaby!:-) since it’s musical but not sentimental, also is in sections (three sections). I was wondering how or when during the writing process (e.g. at the beginning, during the middle, at the end) you arrived at these overriding frameworks in both books. The way that you’ve arranged the work is of interest to me. In a lullaby without any music I wonder similarly how you came up with, as an idea, the framework within the first section also. I wrote a book titled EXHIBIT C (Ahadada, 2008) where I did something similar in terms of numbering sections labeled with nouns.

JB: How did EXHIBIT C manifest itself? Was the title a reference to a science or art project? In Derivative all the poems were written on separate occasions as discreet poems. Only the final section, “Hypnogogic Diary”, was written as a series poem and it was the last thing written. I had this manuscript throughout undergraduate and graduate school, so I spend a lot of time ordering it and working it over. My primary teachers were Gene Frumkin and William Olson.

lullaby was written as a series from the beginning. I was spending a lot of time in my native New Mexico and in Oregon with my mother-in-law who is a master gardener and nature/hiking enthusiast. I was thinking about “field guides,” and I wanted to make a “field guide” about my life. Then, I wrote [Husband] inspired by a poem Lisa Jarnot wrote for Thomas Evans. Finally, I wrote the California section, which was supposed to be a study on my maternal family. I just sort of put them all together. Again, I had help. In this case, in a workshop by Lisa Jarnot. My next book (due this summer by THEEENK) also is a series.

Has moving to Japan affected how you write you poems? I found that the deepest effect on my writing, the biggest change, has come from motherhood.

JN: Thanks for your questions. EXHIBIT C was my third book, hence “C” as a 3rd item. The title seemed apropos also being sort of plebian in that a lot of the poems reference pop culture in the U.S. and Japan; that wasn’t the only influence but a main influence. So it was kind of like here is this stuff from pop culture, let’s examine it (as in a courtroom) together — there’s a bit of whimsy or humor in it also but – of course I’m a fan of the tongue-in-cheek in poetry.

Congratulations on your forthcoming book with THEENK — an interesting coincidence because I have just recently finished a chapbook project with its associated chapbook publisher, Hank’s Original Loose Gravel Press (wildblacklake published in March 2014; a great publisher to work with; the chapbook is also mentioned by Pam in the review shared above of FLUX)! Is the THEENK book your Autobiography/ Anti-autobiography manuscript that you shared with me? I thought we might perhaps talk about that too, though I still have a few questions about your earlier two books.

As to your question about moving to Japan, it’s affected everything I think. The influences in the poetry are not always obvious to people who aren’t familiar with Japan (for example if I use a line from something Japanese that I’ve translated into English — a literary work, or a saying, or a song) though some would be obvious to almost anyone from anywhere if I use something with a well known connection to Japan, something symbolic. I’ve been greatly influenced by Japanese literature, language and culture including poetry and everything in my everyday life in the sticks here; the influence gets stronger in a way with each book, maybe. But I often take something Japanese and subvert it, e.g. in the case of traditional Japanese forms like haiku I borrow something from haiku (e.g. in brief stanzas where the concrete becomes abstract) without actually trying to write haiku exactly, especially since in recent years I seem to write for the most part rather long poems rather than short ones, but those may be composed of small elements inspired in some cases for example by the idea of haiku or another traditional Japanese form. I’m writing something now that isn’t haibun (but is inspired very much by haibun as is true of some sections of FLUX) that also contains some “haiku-esque” sequences within it, e.g. prose alternating with lineated work.

As to your question about moving to Japan, it’s affected everything I think. The influences in the poetry are not always obvious to people who aren’t familiar with Japan (for example if I use a line from something Japanese that I’ve translated into English — a literary work, or a saying, or a song) though some would be obvious to almost anyone from anywhere if I use something with a well known connection to Japan, something symbolic. I’ve been greatly influenced by Japanese literature, language and culture including poetry and everything in my everyday life in the sticks here; the influence gets stronger in a way with each book, maybe. But I often take something Japanese and subvert it, e.g. in the case of traditional Japanese forms like haiku I borrow something from haiku (e.g. in brief stanzas where the concrete becomes abstract) without actually trying to write haiku exactly, especially since in recent years I seem to write for the most part rather long poems rather than short ones, but those may be composed of small elements inspired in some cases for example by the idea of haiku or another traditional Japanese form. I’m writing something now that isn’t haibun (but is inspired very much by haibun as is true of some sections of FLUX) that also contains some “haiku-esque” sequences within it, e.g. prose alternating with lineated work.

Your question about Japan brings me to another of the questions I have about your two books already in print. Japan is mentioned on page 50 of (a) lullaby without any music — I wanted to know more about what you are referencing on this page — and in Derivative of the Moving Image is a Murakami quote on page 53 and then there are references to China in this book: Li Po on pages 18 and 19 and on page 50 you mention a Chinese wife. So I’m wondering what connection to Asia or Japan and China you feel, curious as to what prompted these parts of your books.

JB: Wow! That’s a good question. I never thought of it before. I have no special affinity with China. Those first quotes just came from incidents – a crush on a man who had been married to a Chinese woman and (separately) a trip to Li Po’s bar in Chinatown in San Francisco. That poem also references my dear friend, the artist Jim Campbell. The final part of the book is dedicated to him. I do have more of a connection with Japan. I am a huge Murakami fan (or was until he reached rock star status!) I love Japanese novels; I was obsessed with Banana Yoshimoto for a while. I have this idea that all Japanese novels contain a body of water and a dead person or ghost. Although I think this may be made up. A few years ago, my son became obsessed with Japanese culture, and he took a year and a half of language classes at the Tenri Center in New York. Through them, I was exposed to some contemporary Japanese art. Ozu is one of my favorite filmmakers, and then, of course, there is the connection between Cid Corman, who really flourished there, and Larry Eigner. I know hardly anything about Japan and wouldn’t pretend to; but there are all these connections I have never thought of before. I may have asked before, but why did you move to Japan?

JJN: Thanks for asking. I moved to Japan a long time ago with the idea that I wanted to expand my intellectual, aesthetic, cultural, emotional (and spiritual?) horizons. When I came here there were a lot of jobs fortunately (though the job market certainly is different now but work is still available particularly if you have the right connections). I ended up falling in love and getting married here and the marriage kept me from leaving when things got tough! At this juncture I’ve been here a while now and I am used to the language, culture and so on and very happy with my life here. Although my undergraduate degree is a creative writing degree with a poetry specialization, my graduate work was in linguistics. Part of what brought me to Japan was research about Japan I became familiar with while still in the U.S. in the subarea of sociolinguistics that I found fascinating. I was convinced coming to Japan would really shake up my reality due to the great differences I was learning about in the rules Japanese people follow when communicating as compared with Americans (that turned out to be quite true).

I’m not a huge Murakami fan tho not anti-Murakami either. I read a number of his short works recently in Japanese. I also went through a Yoshimoto Banana phase! I loved np in particular, that book made quite an impression on me. Recently I have read in Japanese some works of Akutagawa Ryunosuke, whose stories have the dead people and ghosts you mention, e.g. In a grove and Rashomon. Reading Japanese is hard (even for Japanese people) because there are thousands of Sino-Japanese characters to memorize and these characters frequently have more than one meaning and more than one reading (pronunication) and additionally the number of homonyms is huge. Also literature may contain some seldom-used characters. I’m no genius whatsoever with these characters, I struggle with them, forget them and re-learn them, etc. I don’t have an excellent visual memory. But the spoken language is not hard once you get used to the syntax, the grammar is fortunately quite regular compared to English, and pronouncing Japanese involves few if any obstacles for an American.

Of course when you live in a foreign country your native country and its culture and its language is thrown into relief so you notice things you didn’t before. This heightened awareness may be useful for writing poems. I mean in particular, in a way English is in part a foreign language to me now because it’s not the language of daily life in the small city in which I live. I also spend a lot of time in nature including in a remote mountain region of Japan (where I am now) where I feel very far away from everything! but close to the earth — a place where I encounter more animals than people in daily walks, where few people live year round but the people who are here are very kind and friendly. I have come to identify quite closely with ecopoetics (as well as feminism and anti-capitalism even though or because I’ve personally benefited from capitalism, but who doesn’t have guilt about what they have when many others have so little? My interest in feminism goes back to my high school days so it’s been a long relationship). From a young age as a child living in a Chicago suburb I was interested in other people and cultures and at that time didn’t understand white racism, sexism and homophobia; I was certainly aware of those things. I couldn’t wait to leave the suburbs to live, from the age of 17, by myself in the more multicultural and free (freer from surveillance) city of Chicago. In many cases I was a minority (in terms of skin color, language, or other attributes) in the Chicago neighborhoods I chose to live in. It’s not the same as being a minority in Japan of course but I’ve reflected on it, that maybe I’ve always wanted to learn by surrounding myself with things and people outside my normal everyday existence. I still feel that way; perhaps I am especially comfortable in the observer (and thus learner) role — it may be part of why I’m a poet.

Working within a Japanese organization you often spend your free time with colleagues so for me that was a downside of the local work world because I like to meet people from other (varied) walks of life (I think varied experiences are important for a poet). A full time job in Japan can leave you with little time when you work long hours and then spend what free time you have with the same people you work with; I’d also say it is geared for married men who have wives taking care of everything else in life (particularly out in the conservative heartland where I live; it’s funny being a flaming liberal living in a conservative place!) so they can devote themselves single-mindedly to jobs (this makes work life problematic for many women). This was part of but not the only reason I left a full time tenured university position (exhaustion, difficulties in achieving a balanced life and in assuming family responsibilities, having to live apart from my husband, etc.). In some ways your job being your life may be attractive but it’s still a kind of limited life. The limits could be part of the attractiveness, like being wrapped in a blanket, of course. You are freed from thinking about many things as many choices are already made for you. But I don’t know that that lifestyle much suits a poet and thinker.

As far as Japanese poetry I feel there is still much for me to learn. One poet I’m reading now is Hagiwara Sakutaro. I am very fond of Tamura Ryuichi. There are a lot of women poets whose work I am also trying to read in their original Japanese recently. One is Kora Rumiko; another Minashita Kiriu. Other than the many Sino Japanese characters another obstacle is not having grown up here there can be cultural references in poems I may completely miss so it’s often good to have a guide if possible. But I like stumbling around with languages, I stumble around with reading poems in my only intermediate level school French and try to read poems in my poor Spanish etc. and other languages. My interest in haiku and other more traditional forms as opposed to contemporary Japanese free verse is in a way somewhat recent or was recently heightened I think you could say in part because I have met a number of haiku and tanka poets in recent years who prompted me to study that kind of work more closely.

Looking at your books I notice one device you use is repetition. I love repetition in a poem or book of poetry and use it in various ways myself. But for example in (a) lullaby without any music there are quite a lot of birds, not just in “the Field Guide to Flying” section but throughout the book. The word “body” is used a lot too, and not just in the “body” section of the Field Guides. “Dream” also appears frequently and “sleep” a couple of times. “Translation” I noticed in about four instances and because I live in Japan I was curious about your use of this word. Do you have any comments about repetition as a poetic device or about any of these words in particular as far as their relevance or importance to the work as a whole?

JB: I don’t have much to say regarding the repetition, except sometimes when I give readings, I notice it profoundly, and I feel lazy and embarrassed. So much of my poetry (all of it?) is written on what feels like an unconscious level — the exception I would say is punctuation. I just sort of digest what I am reading and the environment around me and the poems sort of write themselves. I do think my fixation on the metaphor of the bird derives from the fact that I have cerebral palsy and move through the world somewhat slowly and laboriously. I would like to know what “fastness,” or flight feels like. I also sleep a lot, and I’ve always had very vivid dreams, and this might sound funny, but in my head often my dreams and “reality” become mixed.

When I was recently studying Cid Corman, I found an article in Jacket 2 by George Evans regarding Corman’s time in Japan . Evans was discussing the fact that Japanese culture can be particularly excluding to foreigners, but in a very polite manner. Evans described Corman’s experience of “fitting in” and more or less becoming culturally Japanese. I wonder if you had a similar experience? Also, is Corman well regarded in Japan as a poet?

Finally, I recently heard a lecture about sex workers assisting people with disabilities in intimate situations. Have you heard anything about this? Is it a big deal in Japan? How does Japanese culture regard people with disabilities in general? Are they part of the educational system and workforce?

JJN: I like your comments about the semi-conscious and dreams. And in your books I like the repetition because it has a unifying effect on free verse and ties the books together, or so I think. I sometimes repeat phrases in a book that I consider to be like “refrains” in a musical composition. I like the often obsessive nature of repetition in poetry including repetition of sounds so you know poems that rhyme, formal poems where lines are repeated like in a pantoum, or words repeated like in a sestina etc. So I think repetition is a great thing and I like how it works in your poetry. I thought those words maybe have special significance because the book is dreamlike and you refer to the body (including of course your own body) and so on — for somebody who has not yet read your book I think knowing that these words play a kind of key role (I believe!) can help familiarize the reader with some important thematic concerns. And I like how dreams and reality become mixed in the book just as you say they do in your head, and the notion of poetry itself as a kind of translation!

As far as your question — I think Japan has changed a lot since I first moved here. White foreigners were more of an oddity when I first moved here but now somewhat less although since I live in the boonies I am a visually conspicuous person. Many Japanese realize there are foreigners who learn the language and culture now, not just tourists, and try to fit in to Japanese society, or may have even grown up here (although I did not), versus people who just come for a short stay and then leave. If you make the effort to learn the language and culture you can feel a part of things. I’m very comfortable here though occasionally there are annoyances of course. There are narrow-minded people in every country in the world so you know if you are looking for open-minded people as anywhere you pick and choose the people who will be part of your inner circle. I’ve met great people here, both expats and Japanese. As far as people being politely excluding, I see nothing polite in it, but it’s only some people. There are rigid personality types in every country. I know so many great people in Japan, so I feel very happy here. In general people are pretty nice here.

As far as life for people with disabilities here, it’s hard for people with disabilities to get jobs. Recently I got a (Japanese) catalog in the mail, advertising supplements, but with an ad also selling T-shirts made by a group called Able Art; all of its employees are persons with disabilities. There are some efforts to make public transportation and buildings relatively more barrier-free; these efforts aren’t enough but at least there have been attempts to improve things. NHK (the government-affiliated television station) tries to play an educational role and there are many programs about people with disabilities aiming to educate the public. What effect these programs have is hard to say however. There’s much that needs to be done. In some ways Japanese culture can be rigid / inflexible (rule-governed, time-honored ways of doing things followed simply because it’s always been done that way, etc.) and it may be hard for companies to make changes that accommodate everybody due to rigidity and other factors even if there are government incentives for hiring people with disabilities. This is true not only though especially for people with disabilities but even for example for women as I alluded to earlier in male-dominated fields (which is most fields) — there can be a kind of rigidity, and as I also mentioned this may be more prevalent in the heartland than in the larger cities perhaps. Jobs that expect you to work long hours, evenings, weekends etc. — that’s very difficult for many people, e.g. women who probably also have household and childcare tasks to do (men do those things not as much as women); there’s often not flexibility. As far as sex work, that’s not an area I know a lot about or is spoken about so openly. Sex work is everywhere but it’s not polite to talk about it and it’s part of underground criminal activity. As far as education, it’s been the norm for students with disabilities to mainly take classes apart from able-bodied students as far as I know and most teachers with disabilities probably work in disability education, although things are probably changing a lot. We don’t really even see that many people with disabilities in public or in jobs, though sometimes. So as I said there’s really a lot that is needed to be done. Also, persons with disabilities are financially supported by relatives when possible as opposed to public aid which is I believe given only when there is no possibility of family support. I read about some persons with disabilities complaining that for example they had bad relationships with family members and thus did not want to be forced to be financially dependent on them but wanted access rather to government funds; I read about this not long ago, sometime last year I believe. Laws can change of course but the fact that persons with disabilities are mostly invisible in society (though there are some recent improvements) says a lot about how things are not very good.

As far as Japanese people’s opinions about poetry, they would be mostly restricted to Japanese poets who write in Japanese. Poets who write in English aren’t well known except to English literature scholars who know especially famous dead poets because that’s their research area, so few would know Corman other than the tiny English-speaking expat poetry community in Japan and some English lit specialists. Although Japan is not as anti-intellectual as the U.S. is, poetry was probably more revered by older generations than by youth today. For example I did some work in adult ed where many of my students were retired and they knew not a lot of Japanese contemporary poets but some, more than a few. But as a university teacher in recent years I learned few of my students could name more than one or two still living Japanese poets! and these would only be poets who appeared in for example their junior high school textbooks. I thus created a new course — I was already teaching a course in American poetry, and others in American and British poetry — which was comparative poetry where I introduced students to Japanese contemporary poets. The course went very well, a lot of fun both for me and the students. Another example: I attended a collaborative poem recitation and discussion event in my small provincial city last November (funded by the prefecture) and noticed almost everybody in the audience — it was a well publicized event on a Sunday afternoon — was elderly, retirement age. I was rather disappointed that young people were not interested — the participating poets included younger poets, there was a span of ages and the senior-most poet was not that old — and my friend who I was with who attends the event every year said this was always the case (a mostly elderly audience). Another poetry reading I attended a few years ago had a similar kind of audience of older people. However, in Tokyo the audiences are more varied and there will be more people of various ages including younger people in attendance.

So out here in the heartland, you know, it seems that interest in Japanese poetry is not much. Many bookstores have no poetry on their shelves or else they have some children’s verse and a few mainstream poets’ works. I felt thus a “duty” to create the comparative poetry course — there are many wonderful Japanese poets, students should know about them, and if they were learning about foreign poetries from me they should learn as much or actually more about poetry from their native country I felt/feel strongly. There are some TV programs about poetry but often these are educational programs of NHK related to traditional Japanese culture thus about for example haiku (including haiku contests) or poetry from early in Japan’s literary history. So those efforts are part of academics and traditional cultural preservation but outside of Tokyo there is maybe not much effort or interest in contemporary Japanese poetry outside of small groups of literary types. There is a need for more teaching of contemporary Japanese poetry and more support for it. Though bookstores mostly ignore poetry, local libraries have a better selection even in the sticks; there are some poetry specialty bookstores that most people aren’t aware of hidden on small streets in some large cities. I visited a poetry museum in central Japan not long ago but it was devoted to one particular poet versus poetry in general.

Japan has become increasingly more internationalized of course like the rest of the world affected by media and travel. There are some interesting pockets of internationalization even in the boonies where I live. For example I attended a production of Faust at a theater a few blocks from home recently with my husband which was in German (though with Japanese subtitles displayed on a LED screen) and the collaborative poem event I mentioned in some years has included foreign poets. I saw a New York Met production from a few years ago of Gounod’s Faust on satellite TV the other day! The reach of the U.S. is global, moreso than the reach of Japan is — I’m constantly reminded of this daily. There was a small poetry exhibit held in the same building that houses the theater recently based an exhibit from the abovementioned poetry museum in another small city in this prefecture. A good thing was both made efforts to include stuff to appeal to kids as well as adults and at both some parents brought kids with them who appeared to have a good time. It would be fantastic to have a poetry museum introducing a variety of poets or other literary space housed in the theater building, something to attract the general public and people of various ages. I went to a ramen museum years ago in the city — I’d prefer a museum or space devoted to verse versus food! Ramen you can find everywhere easily after all — it doesn’t need to be promoted. The idea that presumably things are “supposed” to cater to the masses is not good.

I’d like to return to the theme of disability that began our interview. Your work Autobiography / Anti-autobiography opens with a quote from Virginia Woolf’s On Being Ill which links illness with mysticism and transcendence; the first lines of yours in your book are:

--

--

to walk means to fall

to thrust forward

to fall and catch

the seemingly random

is its own system of gestures

based on a series of neat errors

falling and catching

to thrust forward

sometimes the body misses

then collapses

sometimes

it shatters

with this particular knowledge

--

Page eight contains these lines:

so that, the mother might

say your child must be angry

because you are disabled

so I told her, your child

must be angry

because you are a bitch

and the children ask

why do you talk like that?

and I ask them

why do you talk like that?

and children grow up

knowing this is ordinary

--

and on page ten we find:

To be crippled means to be institutionalized, infantilized, unemployed, outcast, feared, marginalized, fetishized, desexualized, stared at, excluded, silenced, aborted, sterilized, stuck, discounted, teased, voiceless, disrespected, raped, isolated, undereducated, made into a metaphor or an example. To be crippled means to be referred to as retard, cute, helpless, lame, bound, stupid, drunk, idiot, a burden on society, in/valid. To be crippled means to be discounted as a commodity or regarded as mere commodity.

--

I hope I’m not giving away too much of the book! I find this book, also, compelling, specifically the way that you merge lyricism with non-lyricism and the personal with the political. Do you have any closing comments you’d like to make about your work, this work, or new work / work in progress such as Drugs are his mistress which I also read with great interest?

JB: I don’t have much to add. Just that I hope my work, specifically the poems about disability, helps people gain a new perspective that there are people with disabilities in the world living full, complex lives. That disability merely means to think or move differently than the average person. It’s not a death sentence or a lament. It just is.

JJN: I hope many people will discover your poetry and other projects and gain this perspective, and others. Thanks so much Jennifer for engaging in this conversation with me! You seem to have a very Japanese sense of modesty about your considerable talents. Many thanks indeed! Please visit me in Japan someday.

JJN: I hope many people will discover your poetry and other projects and gain this perspective, and others. Thanks so much Jennifer for engaging in this conversation with me! You seem to have a very Japanese sense of modesty about your considerable talents. Many thanks indeed! Please visit me in Japan someday.

(August 2014)

Originally from the U.S., Jane Joritz-Nakagawa (janenakagawa AT yahoo DOT com) has lived in Japan a long time. She’s currently working on her eighth book of poetry.