Gertrude and Alice in Vichyland — Charles Bernstein

Presented as the plenary lecture at the first meeting of the European Stein Network in Paris on November 26, 2016. The meeting was organized by Isabelle Alfandary (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle) and Vincent Broqua (Université Paris 8). For documentation and related material, click on images and links.

Graphics and page design are mine.

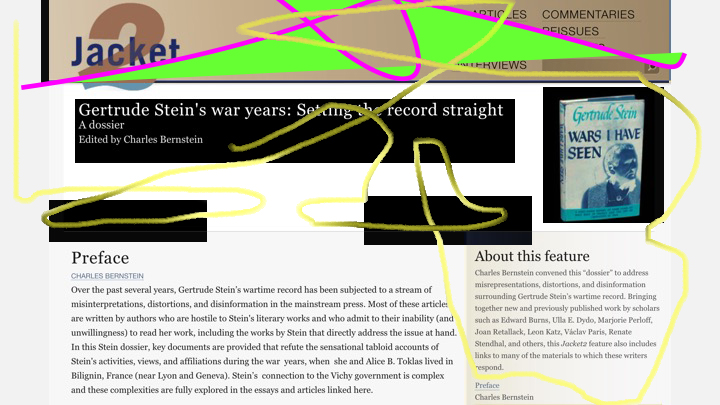

This presentation follows up on “Gertrude Stein's War Years; Setting the Record Straight,” a dossier I edited for Jacket2 in 2012:

Governing Criteria for This Report

EVIDENCE

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

MATERIAL TEXT

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, Aix-les-Bains, France, circa 1927 (Yale Collection of American Literature)

My undergraduate thesis, Harvard College, available as an Asylum’s Press Digital Edition.

My undergraduate thesis, Harvard College, available as an Asylum’s Press Digital Edition.

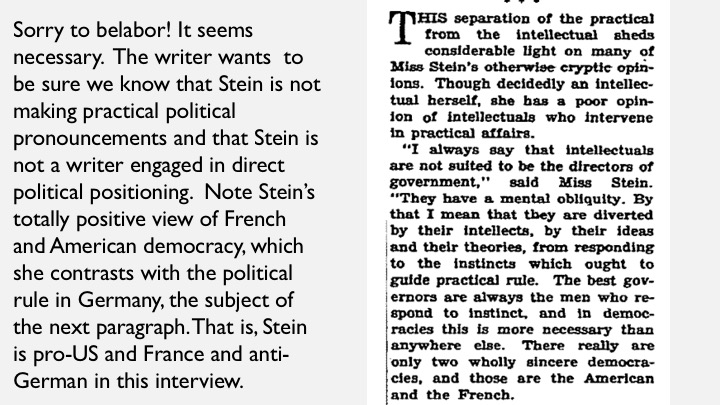

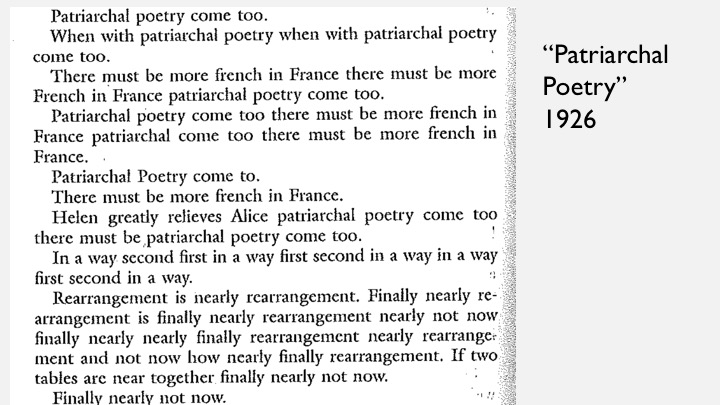

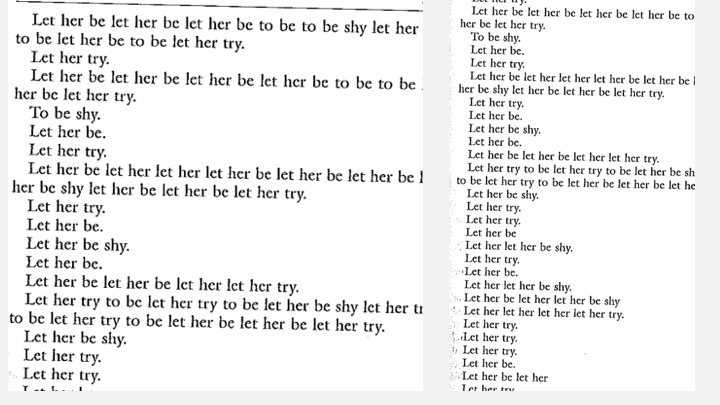

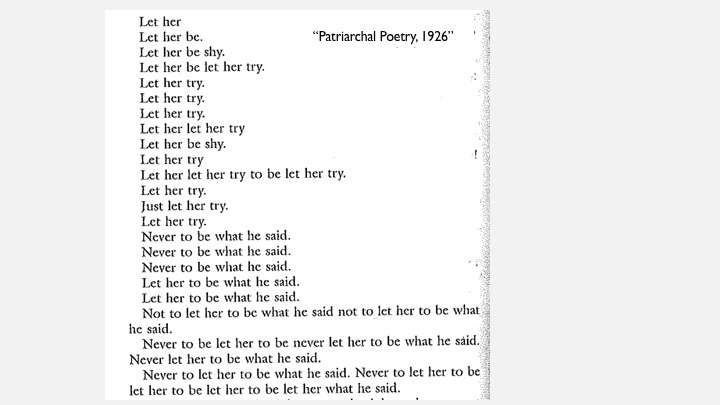

from Pitch of Poetry –– pp. 83 (above) and 97 -98 (below)

from Pitch of Poetry –– pp. 83 (above) and 97 -98 (below)

#BROWN-BAITING

Updated from the 2012 dossier, here are links to a number of the recent articles (and one notorious older one) that denounce Stein for her wartime record.

1. Bill Berkowitz, “Did You Know Gertrude Stein Allegedly Advocated Adolf Hitler for a Nobel Peace Prize? It Gets Worse,” The Buzzflash Blog, September 12, 2011.

2. Richard Chesnoff, “A Nazi Collaborator at the Met,” New York Daily News, April 29, 2012.

3. Alan Dershowitz, “Suppressing Ugly Truth for Beautiful Art,” Huffington Post, May 1, 2012.

4. Allen Ellenzweig, “Auntie Semitism: Gertrude Stein’s Ties to Nazis, Revisited at the Museum, Shouldn’t Eclipse Her Nurturing of Young Artists,” Tablet, May 8, 2012.

5. Emily Greenhouse, “Gertrude Stein and Vichy: The Overlooked History,” New Yorker, May 4, 2012.

6. Emily Greenhouse, “Why Won’t the Met Tell the Whole Truth about Gertrude Stein?.” New Yorker, June 8, 2012.

7. Philip Kennicott, “Gertrude Stein in Full Form at the Portrait Gallery,” Washington Post, October 21, 2011.

8. Michael Kimmelman, “Missionaries,” New York Review of Books, April 26, 2012. NYRB declined to print a letter in response by Joan Retallack, Charles Bernstein, and Edward Burns, instead including a response by Kimmelman (July 12) that included the URL of the Jacket2 dossier. See also Kimmelman’s earlier review of Janet Malcolm in the Oct. 25, 2007 issue.

9. Janet Malcolm, “Gertrude Stein’s War,” New Yorker, June 2, 2003 (see also Malcolm’s Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice, Yale University Press, 2007).

10. Sonia Melnikova-Raich, “Exhibit Leaves Out How Gertrude Stein Survived Holocaust,” JWeekly.Com, June 9, 2011.

11. Alexander Nazaryan, “Gertrude Stein Exhibit at the Met Will Now Allude to Her Hitler-loving Past and Collaboration with Vichy Regime,” New York Daily News, May 7, 2012.

12. Natasha Mozgovaya, “Obama Corrects Controversial Jewish Heritage Month Proclamation,” Haaretz May 3, 2012.

13. Hunter Walker, “Local Politicians Get Met to ‘Disclose Gertrude Stein’s Nazi Past,’” Politicker.com, May 1, 2012.

14. Barbara Will, “The Strange Politics of Gertrude Stein,” Humanities, NEH, March/April 2012. (See also Columbia University Press, 2011.)

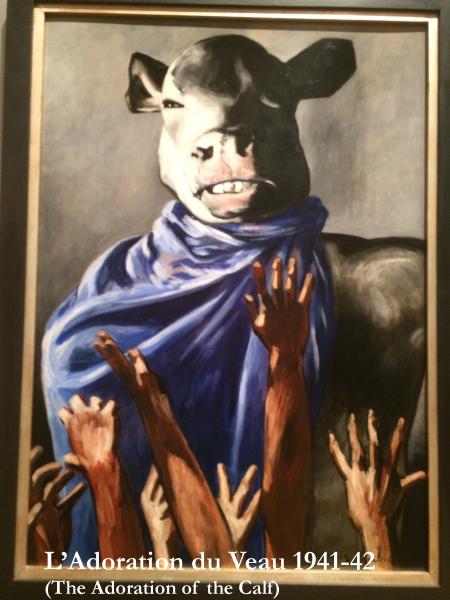

NUMBER OF ARTICLES OR POLITICIANS

DENOUNCING THE VICHY SYMPATHIES

OF FRANCIS PICABIA IN RELATION TO THE

RECENT MUSEUM OF MODERN ART RETROSPECTIVE

OR PROTESTING MoMA’s LACK OF EMPHASIS ON THIS:

0

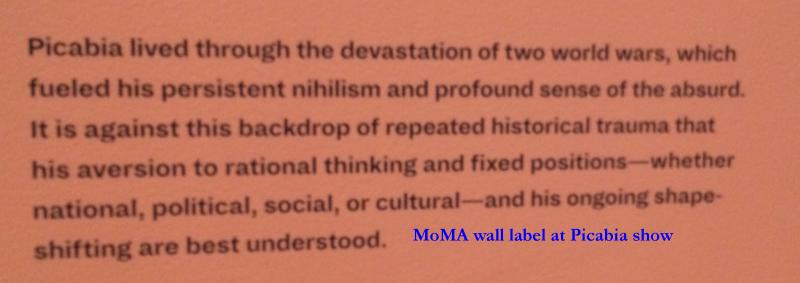

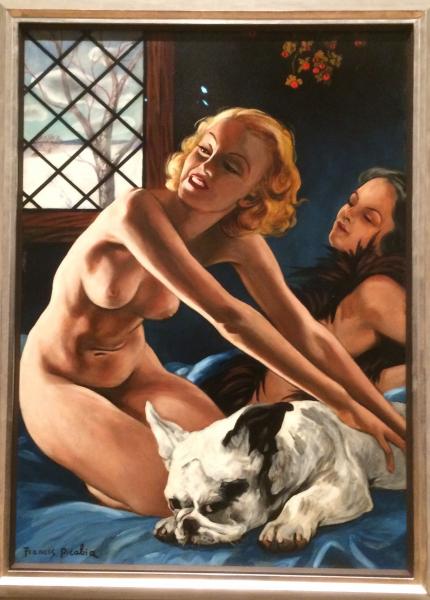

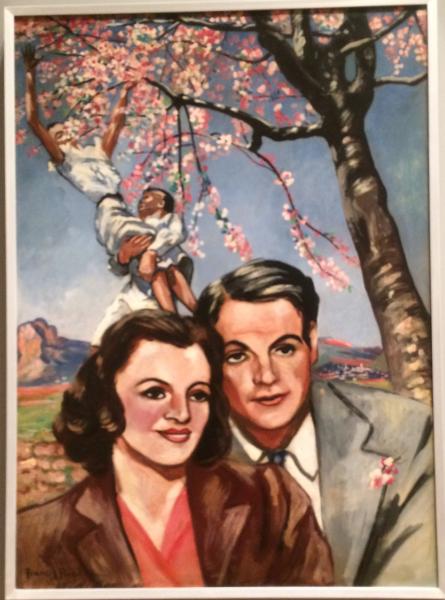

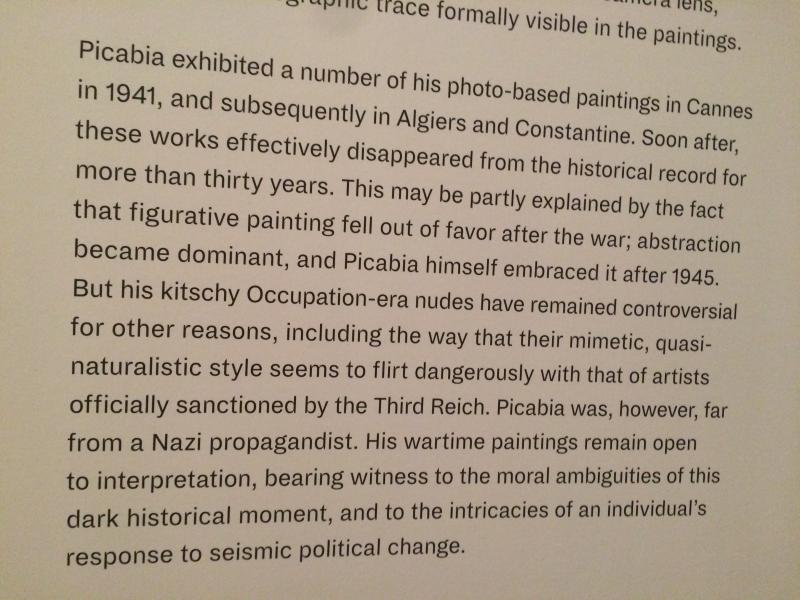

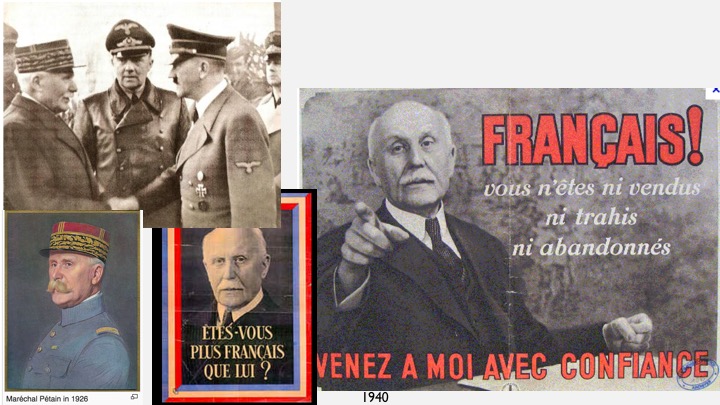

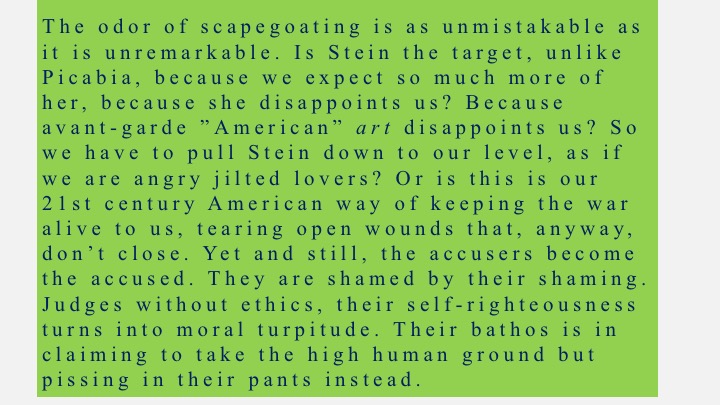

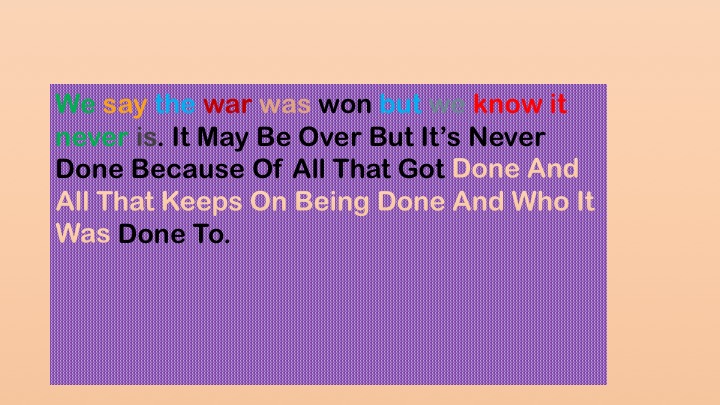

The New York Times Book Review piece on the catalog for this show quotes Michėle C. Cone’s catalog essay “Francis Picabia’s War,” which describes Picabia’s “residence in Vichy France and association with the local Gestapo as ‘confused and confusing behavior’” [Dec. 3, 2016, p. BR64]. In her thoughtful and restrained essay, Cone goes on to “Like his friend Stein, Picabia’s personal life during the occupation was murky.” I make the contrast between  Picabia and Stein’s “murky” behavior to emphasize the stark contrast in treatment. Why was Stein been subjected to such virulent scorn when her family art collection was shown at the Met (with no focus on her own work) while Picabia, subject of a full-scale retrospective of his work, was not? Ironically, some of Picabia’s quite intriguing paintings reflect his “murky” views, which is not the case with any of Stein’s literary works. It’s possible that the discrepancy is the result of Picabia being considered French and Stein American, but, as noted, this is a dubious distinction. It may also be because Stein was a Jewish and Picabia … well, Picabia was not. Perhaps European Jews are held to a different standard, perhaps they are expected to be heroic resistance fighters. Maybe it is because Stein was a lesbian or maybe just because she was a woman. It is also possible that Picabia’s reputation is protected by a powerful network of museums and collectors while Stein had no such institutionally vested supporters. Or that Stein’s poetry still outrages more than Picabia’s painting. Perhaps Picabia confirms what is expected of a man in his situation and Stein betrays expectations, even though Stein and Toklas were at risk of extermination while Picabia was not. In any case the vastly greater interest in Stein’s “murk” than Picabia’s cannot be justified by the historical or aesthetic record. Stein provokes a matricidal and misogynistic ruthlessness on the part of her most devoted haters.

Picabia and Stein’s “murky” behavior to emphasize the stark contrast in treatment. Why was Stein been subjected to such virulent scorn when her family art collection was shown at the Met (with no focus on her own work) while Picabia, subject of a full-scale retrospective of his work, was not? Ironically, some of Picabia’s quite intriguing paintings reflect his “murky” views, which is not the case with any of Stein’s literary works. It’s possible that the discrepancy is the result of Picabia being considered French and Stein American, but, as noted, this is a dubious distinction. It may also be because Stein was a Jewish and Picabia … well, Picabia was not. Perhaps European Jews are held to a different standard, perhaps they are expected to be heroic resistance fighters. Maybe it is because Stein was a lesbian or maybe just because she was a woman. It is also possible that Picabia’s reputation is protected by a powerful network of museums and collectors while Stein had no such institutionally vested supporters. Or that Stein’s poetry still outrages more than Picabia’s painting. Perhaps Picabia confirms what is expected of a man in his situation and Stein betrays expectations, even though Stein and Toklas were at risk of extermination while Picabia was not. In any case the vastly greater interest in Stein’s “murk” than Picabia’s cannot be justified by the historical or aesthetic record. Stein provokes a matricidal and misogynistic ruthlessness on the part of her most devoted haters.

MoMA’s comment that Picabia is “resolutely apolitical” in the gallery with these Nazi/Vichy era paintings is bizarre and does an injustice to Picabia’s work. This kind of “what you are seeing is not what you are seeing” is in marked contrast with the commentaries on Stein, which take the approach “what you are not seeing is what is there.”

PS: J’adore Picabia!

(and his poetry too)

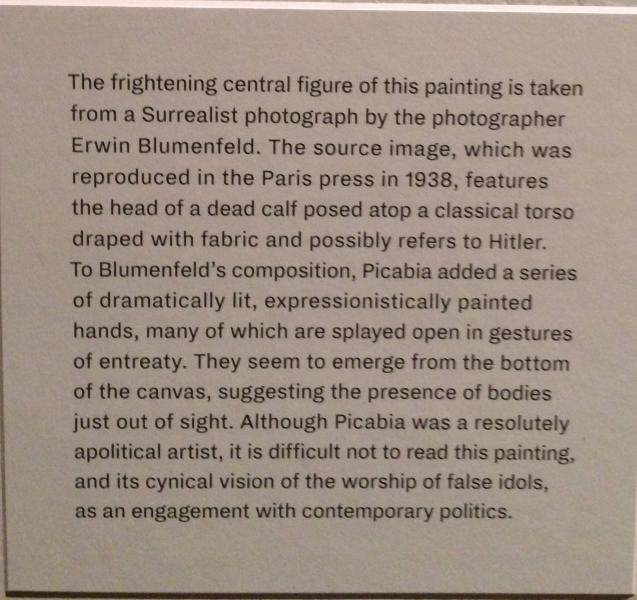

Picabia and me, photo by Elizabeth Willis, 2016.

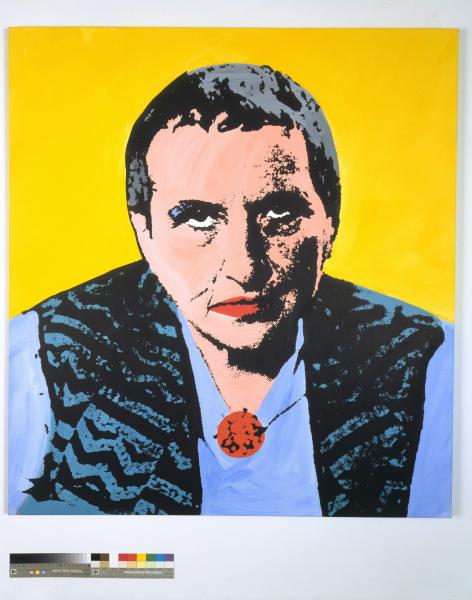

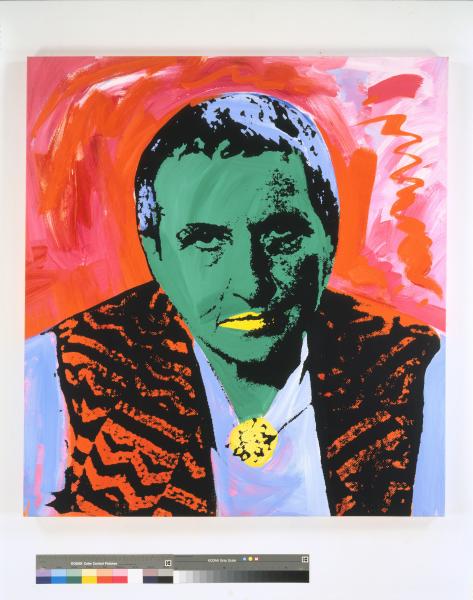

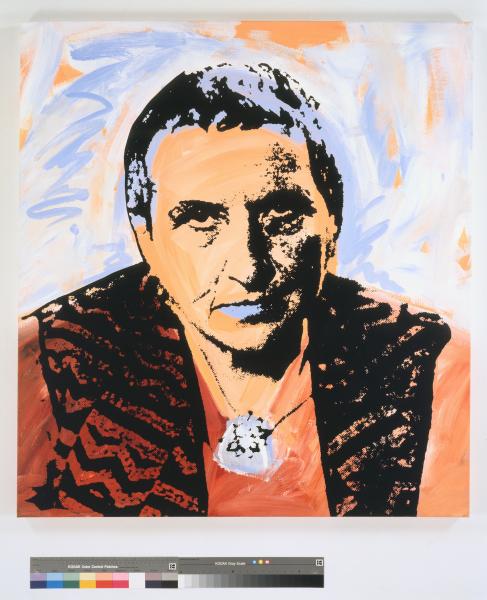

Close-up/sideways view of Picabia’s 1937 portrait of Stein.

THE HUFFINGTON POST

Suppressing Ugly Truth for Beautiful Art

05/01/2012 03:52 pm ET | Updated Jul 01, 2012

Alan Dershowitz, criminal and civil liberties lawyer

The Metropolitan Museum in New York, in its current exhibit on the collection of Gertrude Stein and her family, has made a decision to suppress the ugly truth about her collaboration with Nazism during the German occupation of France. Anyone walking through this beautiful exhibit of the Stein family’s exquisite tastes in art would learn nothing about Gertrude’s horrendous taste in politics and friends.

Stein and Toklas survived the Holocaust for one simple reason: Gertrude Stein was herself a major collaborator with the Vichy regime and a supporter of its pro-Nazi leadership.

Stein and Toklas survived the Holocaust for one simple reason: Gertrude Stein was herself a major collaborator with the Vichy regime and a supporter of its pro-Nazi leadership.

According to a new book entitled by Barbara Will, Stein publicly proclaimed her admiration for Hitler during the 1930s, proposing him for a Nobel Peace Prize. In the worst days of the Vichy regime, she volunteered to write an introduction to the speeches of General Phillipe Pétain, the Nazi puppet leader who deported thousands of Jews, but who she regarded as a great French hero. […]

Stein’s closest friend, and a man who greatly influenced her turn toward fascism was Bernard Faÿ.

Edward Burns in the Jacket2 dossier:In her thinking about political, social, and economic matters, Stein was a conservative Republican with what her friend William G. Rogers called the mentality of a “rentier,” a person of property. She opposed Roosevelt and the New Deal and was more afraid of communism than of fascism. In spite of her close friendship with Picasso, during the Spanish Civil War she did not denounce the revolt of General Franco against the duly elected Republican government.

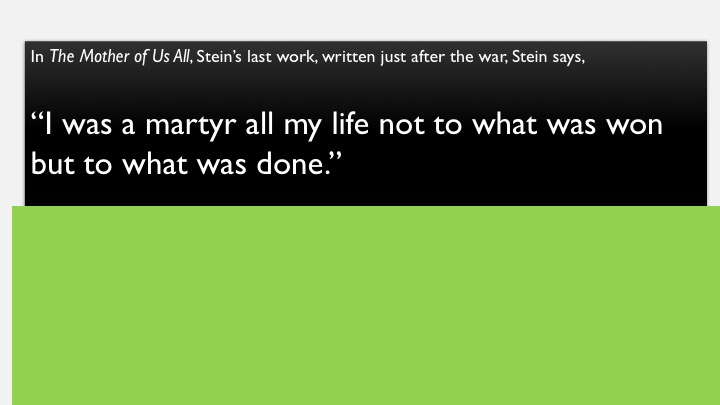

A fact rarely mentioned is that Stein’s name appeared in the “Liste OTTO, ” a list of proscribed writers, published on May 10, 1943. Stein is among the list of Jewish authors, “Juedische Autoren, Écrivains Juifs,” writing in the French language whose works were banned. […] Inclusion of a writer’s name on the “Liste OTTO” meant their books could not be sold and were to be removed from libraries. [image of Stein by Picabia]

René Tavernier (1915–1989) [the Resistance leader and poet] published translations of some of Stein’s earlier works and some new works in his journal Confluences beginning in July 1942. […] Stein’s poem “Ballade” (translated by the Baroness d’Aiguy) appeared in the same issue as Aragon’s “Nymphée” (it was the publication of this poem, a thinly disguised attack on the French and on Vichy, which resulted in the journal being temporarily banned). It seems highly unlikely that Tavernier, who visited Stein during the occupation and remained a friend after the war, would have published her if there had been any indication that her behavior towards Vichy and the Germans had not been anything but correct.

Fontaine, the other journal where Stein published during the occupation was edited in Algiers by Max-Pol Fouchet […] The journal became the voice of resistance poetry in French North-Africa.

Stein’s other connection in Algiers was Edmond Charlot […], heroic defender of freedom and the owner of the bookstore Les Vraies Richesses. He published Stein’s Paris France in October 1941 and her Petits poèmes pour un livre de lecture in April 1944.

Stein’s “Est Morte” appeared in Fontaine 27/28, a special number (June/July 1944) which celebrated writers and poets of the United States including Frost, Williams, Stevens, Eliot, Sara Teasdale, Robinson Jeffers, Conrad Aiken, Lola Ridge, Archibald MacLeish, Horace Gregory, Louise Bogan, Carl Sandburg, Allen Tate, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, Langston Hughes, Frederic Prokosch, Marianne Moore, James Agee, Kenneth Patchen, James Laughlin, and Vachel Lindsay. So important was this issue considered as a sign of French-American solidarity, it was reissued by Max-Pol Fouchet after he moved to Paris in 1945. Again, it is difficult to imagine that someone as sensitive to political issues as Fouchet would have published Stein if he did not have confidence in her stand against Vichy and the Germans.

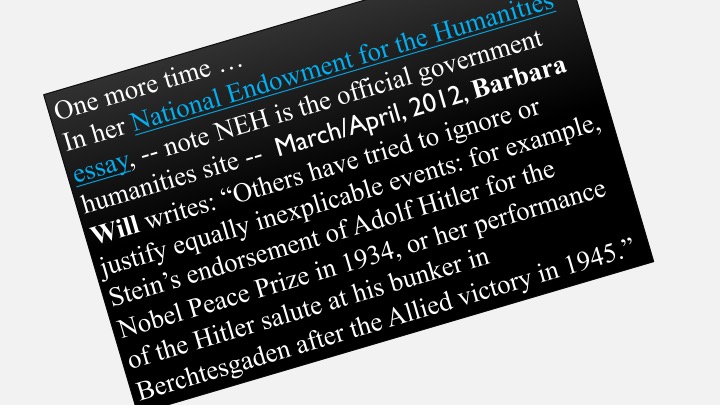

In her National Endowment for the Humanities essay, on the official US government humanities site — March/April 2012, Barbara Will writes:

Yet surprisingly, most of Stein’s critics have given her a relatively free pass on her Vichy sympathies. Others have tried to ignore or justify equally inexplicable events: for example, Stein’s endorsement of Adolf Hitler for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934, or her performance of the Hitler salute at his bunker in Berchtesgaden after the Allied victory in 1945.

Will’s denunciation of Stein for her ironic comment about Hitler and the Nobel Prize is mistaken and she grotesquely mischaracterizes Stein’s salute in 1945. I will return to these points. But first, Vichy. Edward Burns and Joan Retallack give a full response to Stein’s complicated relation with Vichy in the Jacket2 dossier. Allow me to elaborate on a few points.

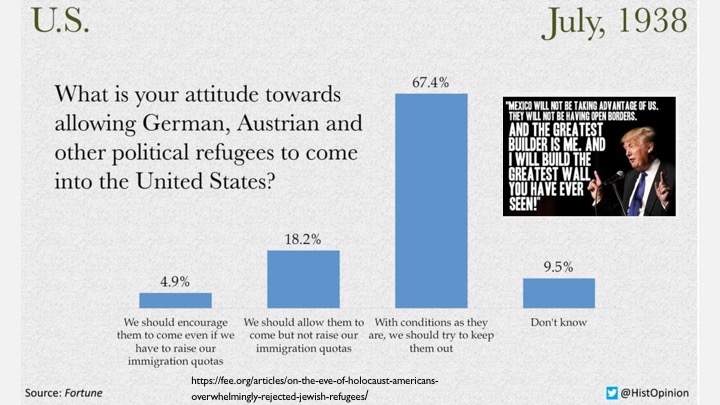

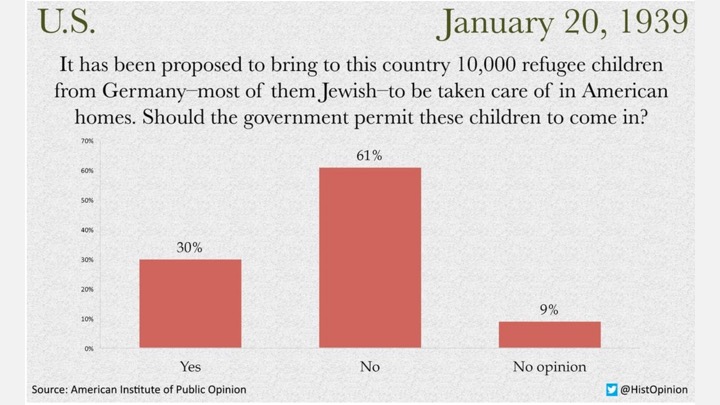

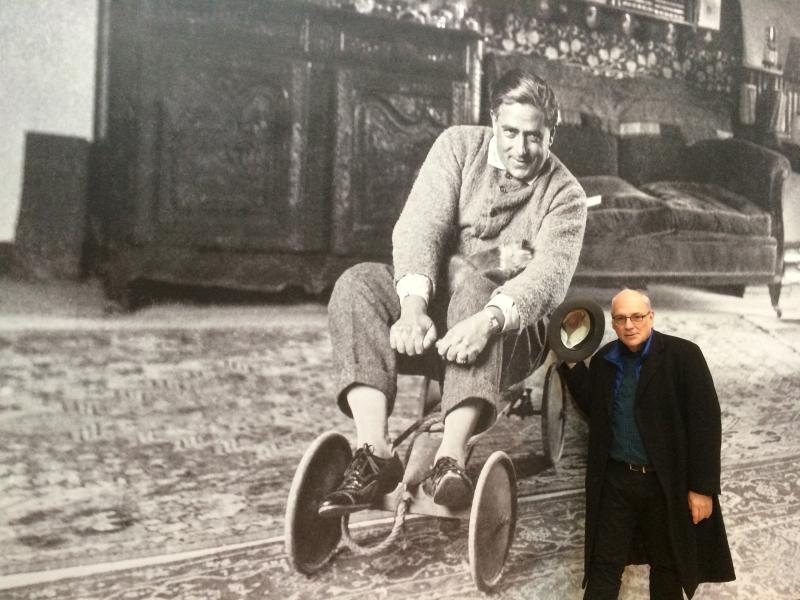

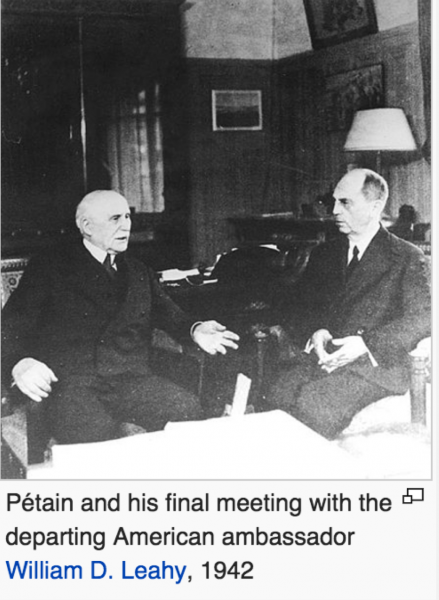

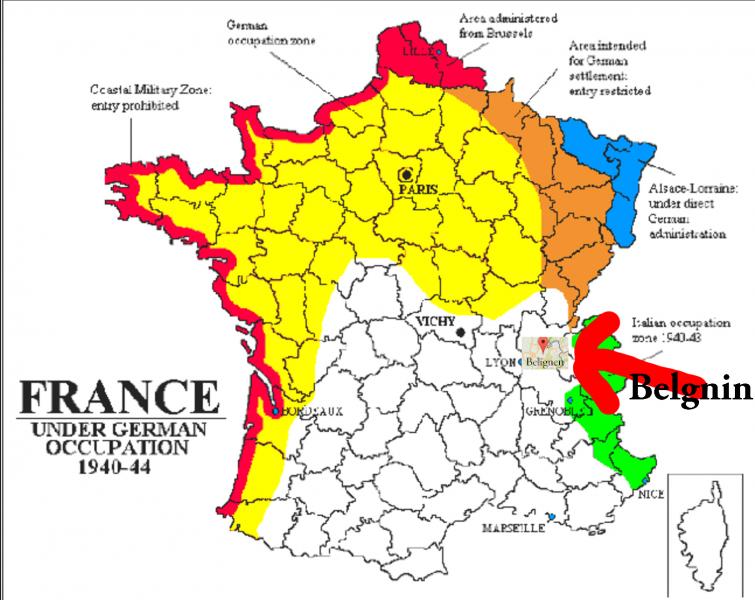

France capitulated to Germany on June 22, 1940, at which time the Vichy regime (in charge of “unoccupied” France) was established; a few days later DeGualle attacked Pétain’s capitulation. FDR did not initially support de Gualle and tried to keep the link to Vichy. Indeed, the US government, under Franklin D. Roosevelt, had diplomatic relations with Vichy from its inception in June 1940:

United States granted Vichy full diplomatic recognition … Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull hoped to use American influence to encourage those elements in the Vichy government opposed to military collaboration with Germany. The Americans also hoped to encourage Vichy to resist German war demands, such as for air bases in French-mandated Syria or to move war supplies through French territories in North Africa. The essential American position was that France should take no action not explicitly required by the armistice terms that could adversely affect Allied efforts in the war. Source: Office of the Historian, US Department of State.

Dec. 20, 1940: from FDR to his appointed American ambassador to France

Dec. 20, 1940: from FDR to his appointed American ambassador to France

Marshal Pétain occupies a unique position both in the hearts of the French people and in the Government. Under the existing Constitution his word is law and nothing can be done against his opposition unless it is accomplished without his knowledge. In his decrees he uses the royal “we” and I have gathered that he intends to rule.

Accordingly, I desire that you endeavor to cultivate as close relations with Pétain as may be possible. You should outline to him the position of the United States in the present conflict and you should stress our firm conviction that only by defeat of the powers now controlling the destiny of Germany and Italy can the world live in liberty, peace and prosperity; that civilization cannot progress with a return to totalitarianism.

Vichy severed diplomatic relations with the United States on at the time of the US invasion of North Africa (eleven months after Pearl Harbor). Pétain considered this an attack on France. On November 10, 1942, Germany invaded Vichy. The Nazis occupied much of so-called “zone libre” (free or unoccupied zone).

According to Edward Burns and Ulla Dydo (p. 406), Stein started to work on her introduction to the translation of Pétain’s Paroles aux Français: Messages et écrits 1934–1941 (published in France in September 1941) in late 1941, about a year and half after the formation of Vichy, when Roosevelt was urging the US ambassador to France “to cultivate … close relations with Pétain.” Stein’s friend, the odious anti-Semite Bernard Faÿ, was close to Pétain, and it was Faÿ who arranged for Stein to take on the Pétain translation. The idea was to win favor for the Maréchal at a time when the US was legitimating the Pétain government. Faÿ, a strong advocate and translator of Stein’s writing, was a scholar of American literature who had written biographies of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington. During the war, Faÿ protected Stein and Toklas, who remained safe; he also safeguarded their art collection, which, as a result, was not looted by the Nazis. Toklas and Stein, friends with the contemptible Faÿ as they were, also had every reason to feel obligated to him.

In addition to fiendish Faÿ, Stein was protected by the people in Bilignin and Culoz, near Belley, where she and Toklas lived during the war. To what extent did her political views conform or diverge from those people in these town. Did her translation of Pétain serve as a “perruque” (wig) in Michel de Certeau’s sense, to protect her and Toklas? Might this be instinctual, toward survival, internalizing the wig, or might it be a more self-conscious survival tactic? Are those two things always different? What happens if we think of Stein as “French” rather than “American”?

In early 1942, Stein wrote to Bennett Cerf at Random House from Bilignin, France, where she and Toklas lived during the war. Stein’s letter was not received by Cerf until February 1946, four years later (Burns and Dydo, p. 413):

In early 1942, Stein wrote to Bennett Cerf at Random House from Bilignin, France, where she and Toklas lived during the war. Stein’s letter was not received by Cerf until February 1946, four years later (Burns and Dydo, p. 413):

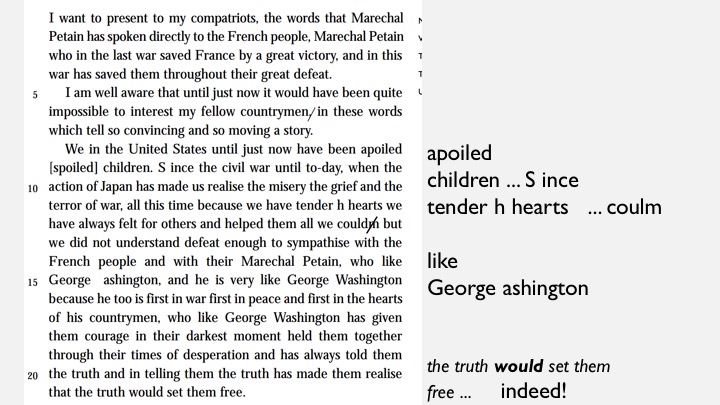

I am beginning at the same time the translation of the Petain to his people, I found the book convincing and moving to an extraordinary degree and my idea was to write an introduction telling how my feelings have changed about him, I have had strong ups and downs and I think it would all do a lot of good, we all now over here can begin to understand that life with its reverses, are not what they were when all went alright. (Burns and Dydo, p. 413)

Stein’s typo-ridden typescript for the introduction to Pétain’s speeches probably was sent to Cerf at the same time as the letter (the typescript was mailed January 19, 1942, according to Wanda Van Dusen’s commendable scholarship in Modernism/modernity, which was published in 1996, the same year as Burns and Dydo more comprenhensive work on the same subject). Stein might well have imagined her letter and typescript from France would not make it in the war mail; in any case, she would have soon guessed that Cerf didn’t get it when she received no reply. So while her labor on Pétain’s writing may have been known in Vichy, and helpful to her for that reason, no actual connection was made to publish it while Pétain was in power or at any time.

Cerf’s noting of the date stamp of Jan. 19, 1942 gives us a general idea of the time frame but perhaps not the exact date as mail in war time France was erratic and postmarks approximate. Burns conjectures that Stein started to work on the translations at the earliest in February 1942 and continued to work on the project for one year, until around January 1943, just months after Vichy broke its ties to the US and Pétain lost power, and when she was probably advised by her friend Paul Genin, who was working with her on the translations, that she should now lay low [Burns and Dydo, pp. 409–410), which once again connects the concern for Stein’s safety related to this vile work. In early 1943, it was dangerous for any Jew in France; the fig leaf of Pétain would no longer disguise the circumcised truth. When she ceased “operation Pétain,” Stein had translated about three-fifths of the French book [Burns and Dydo. p. 410). It’s hard to know what to make of the end stage of this work given the state of the final dissociated holograph (see below), the fact that there is no evidence that Stein made any effort to publish the work apart from the aborted letter to Cerf in January 1942 (a letter she soon must have realized has not been delivered), and given the increased danger to Jews in France at the time she abandoned the project. Vaclav Paris observes, “The work that she probably did during the last three months of her translating — that is, during the period after the US had severed diplomatic relations with the Vichy government — appears half-hearted.” If we look at the material text, we are left with the question of whether Stein was an ardent “Pétainist” or whether she was just going through the motions. Or did her attitude change over time and circumstance, with the “strong up and downs” she tellingly noted in her letter to Cerf?

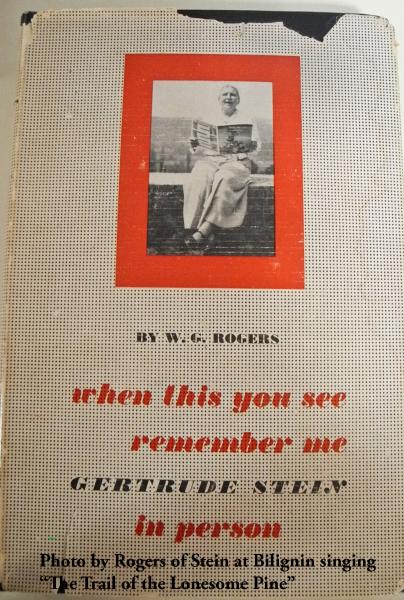

With the excitement of one awaiting liberation, Stein writes to W. G. Rogers in November 1942, at the time of the US invasion of North Africa and the fall of Vichy, “The kiddies the new kiddies are coming nearer and nearer” (p. 211). In her correspondence with Word War I “doughboy” Rogers, Stein affectionately called Rogers the “kiddie.” [W. G. Rogers, When this you see remember me (NY: Rinehart, 1948)]

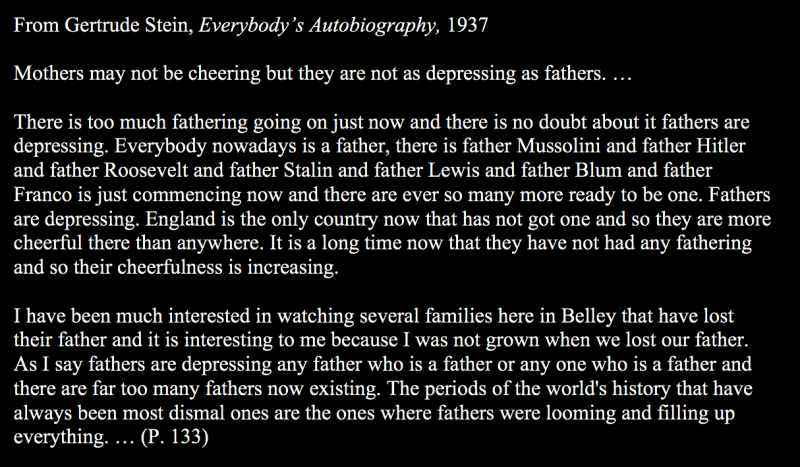

On the one hand, many of Stein’s works take a decidedly antipatriarchal turn. On the other, Stein’s oscillating support for Pétain in early 1942, evident from her pitch to Cerf, is in keeping with some of her political views, as noted. Her remark to Cerf, lost in the mail during the war years, is also a plea for help: “… we all now over here can begin to understand that life with its reverses, are not what they were when all went alright.”

Considering the complexity of Stein’s poetry and essays, the writing in Stein’s Pétain introduction is markedly simplified, not to say idiotic: it sounds like Stein without that Steinian je ne sais quoi. It also erases Pétain’s antisemitism and fascism, painting an outlandishly false picture of him. Take a look at Wanda Van Dusen’s transcription of Stein’s erratic typescript of the 1500 word piece (as noted, sent to Cerf in 1942 but not received by him till 1946). The text was first published in 1996 in Modernism/modernity.

Image at right: “LE SKI”: the remarkably light-hearted cover of Stein’s notebook for the Pétain project. Which way is down?

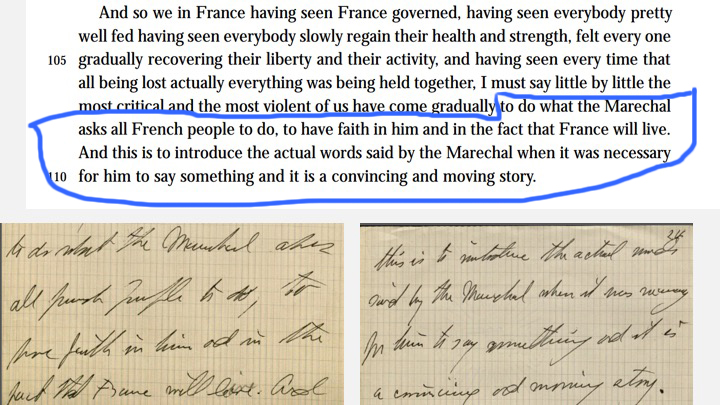

Holograph from Beinecke Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Yale (box 64, folder 1139). The best study of the holograph manuscripts is by Vaclav Paris in the Jacket2 dossier. Paris discusses the oddly wooden literalness of the translations, including providing some transcriptions and giving the source text. So for Pétain’s “Un statut nouveau prélude d’importantes réformes de structure, déterminerales rapports du capital et du travail” Stein writes “A new law a prelude to important

Holograph from Beinecke Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Yale (box 64, folder 1139). The best study of the holograph manuscripts is by Vaclav Paris in the Jacket2 dossier. Paris discusses the oddly wooden literalness of the translations, including providing some transcriptions and giving the source text. So for Pétain’s “Un statut nouveau prélude d’importantes réformes de structure, déterminerales rapports du capital et du travail” Stein writes “A new law a prelude to important  constructive reforms will decide the relation of capital to labor.” Indeed, Paris quotes Barbara Will making a similar observation (though providing the opposite interpretation):

constructive reforms will decide the relation of capital to labor.” Indeed, Paris quotes Barbara Will making a similar observation (though providing the opposite interpretation):

what is most striking about the text is its almost stupefyingly literal rendering of the French original. Translating word by word, Stein completely ignores questions of idiom or style: “Telle est, aujourd’hui, Français, la tâche à laquelle je vous convie” becomes “This is today french people the task to which I urge you.” An idiomatic phrase such as “Le 17 juin 1940, il y a aujourd’hui une année” becomes “On the seventeenth of June 1940 it is a year today.”

Is Stein just going through the motions, appearing to be doing a job while actually undermining it (consciously or not)? Vaclav Paris give us this transcription of a fragment of Stein’s Pétain:

of all of me myself to weaken its unhappiness

misfortune

Here is my word-for-word transcript of the final speech in the proposed collection, a Christmas 1940 greeting that Stein abandoned after two pages. (Click on the image to get the full-size holograph page.)

Stein sent her aborted letter to Bennett Cerf five weeks after Pearl Harbor, which precipitated the US declaring war on Germany. On the face of it, Stein was asking a major American publisher to present the loathsome Pétain in a positive light at a time when America was at war with Germany while maintaining diplomatic ties with Vichy (despite Vichy’s active collaboration with Germany). Stein soon would have realized that her letter did not get to the US. There is no record that any attempt was made to resend it. If the Vichy government was helping Stein, wouldn’t she have been able to contact Cerf? Stein never created a publishable manuscript of the Pétain speeches.

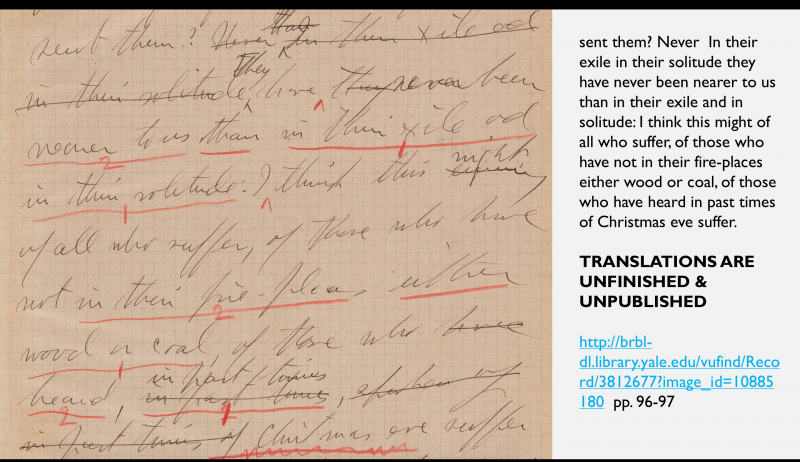

“Pétainistes” were not necessarily supporters of Nazi Germany or Hitler, although they accepted Pétain’s heinous state collaboration (all the details of which were not fully available at the time). Some were self-deluded enough to believe Pétain might protect France against Germany. Stein’s work on the despicable Pétain speeches coincided with the US government’s disturbing recognition of Vichy. So, in the absence of any evidence in her literary work, to make the charges against Stein stick, there had to be more: the disinformation about her support of Hitler combined with her association with odious Vichy official Bernard Faÿ, combined with an insinuation that Stein and Toklas were not at risk in the systematic extermination of the European Jews. (Image: Stein in Bilignin.)

“Pétainistes” were not necessarily supporters of Nazi Germany or Hitler, although they accepted Pétain’s heinous state collaboration (all the details of which were not fully available at the time). Some were self-deluded enough to believe Pétain might protect France against Germany. Stein’s work on the despicable Pétain speeches coincided with the US government’s disturbing recognition of Vichy. So, in the absence of any evidence in her literary work, to make the charges against Stein stick, there had to be more: the disinformation about her support of Hitler combined with her association with odious Vichy official Bernard Faÿ, combined with an insinuation that Stein and Toklas were not at risk in the systematic extermination of the European Jews. (Image: Stein in Bilignin.)

Stein’s account of her wartime experience is found in these two books, as well as her essay, “The Winner Loses: A Picture of Occupied France,” which was published in 1940 in The Atlantic Monthly. I’ve included an excerpt from Wars I Have Seen in the dossier.

Apart from these books, the best firsthand account of this period is in W. G. Rogers’s When this you see remember me: Gertrude Stein in person (New York: Rinehart, 1948). Rogers and Stein became friends in 1917, when he was a “doughboy” (American soldier). In Rogers’s account, in the mid- and late-1930s, even after Munich (September 1938), Stein thought, naively or just wishful thinking, that there would not be another war. For Stein, the first world war was so horrific that she was unable to accept that there could be another war of that scale, or greater, in her lifetime. Rogers says that she ignored or misinterpreted the ominous signs. “I guess I have lost interest in world politics in newspapers and in sides, if they would only leave us alone in our little lost places,” she tells him: the coiner of the “lost generation” who just wants not to take sides (p. 184).

Rogers reports that during the occupation, Stein went native, that is, became part and parcel of the small French village where she lived, adopting many of the political views of the people who lived there, becoming active in war relief efforts, and also suffering severe wartime hardships (pp. 200–209). While Rogers makes his distaste for Pétain clear to Stein when he learns about her translation project, he notes that Stein was pursuing the official US line on Vichy, which held that “Pétain ostensively had fenced off a part of his land from which the conquerors were barred … he had preserved Paris … he has spared” France the “horrors suffered” by Norway (p. 214). The US attitude, says Rogers, encouraged pro-Pètain sentiment in unoccupied France:

It cannot be denied that, in defending him, Miss Stein spoke not only for herself but for many Frenchman who at least in 1940 and 1941 believed, like our own government and with even more supposed reasons for it, that he had done his best for his country. Nothing came of the proposed translation, and since Miss Stein had undertaken it at a time and in a place where complete information was not available, it might be dismissed by itself as an unfortunate error of judgment. (p. 214)

Of course, Pétain had not done the best for his country. And while Stein told Rogers she disliked Pétain’s patriarchal affectations — “his way of saying I Philippe Petain [sic]” — still “the difference between occupied and unoccupied is not technical but fundamental and don’t you forget it” (a point Stein also makes in Wars I Have Seen) (p. 215). Rogers dryly comments: “If I had believed that Pétain helped to save my neck, I too might seek to exculpate him …” (p. 215).

Of course, Pétain had not done the best for his country. And while Stein told Rogers she disliked Pétain’s patriarchal affectations — “his way of saying I Philippe Petain [sic]” — still “the difference between occupied and unoccupied is not technical but fundamental and don’t you forget it” (a point Stein also makes in Wars I Have Seen) (p. 215). Rogers dryly comments: “If I had believed that Pétain helped to save my neck, I too might seek to exculpate him …” (p. 215).

Rogers makes clear that Stein’s allegiances were strongly pro-US and anti-German (p. 212). He notes Stein’s surge of American patriotism after Pearl Harbor and that the townspeople rallied around her as an icon of US resistance to Germany and the Axis powers, eyes tearing as they listened to the “Star Spangled Banner”: “At present we are most busy being Americans, everybody has so much faith in us, as we are their only hope …” (p. 208). Stein writes that her shock about Pearl Harbor is only relieved by her chanting a rhyme that the US will bomb Tokyo (p. 209).

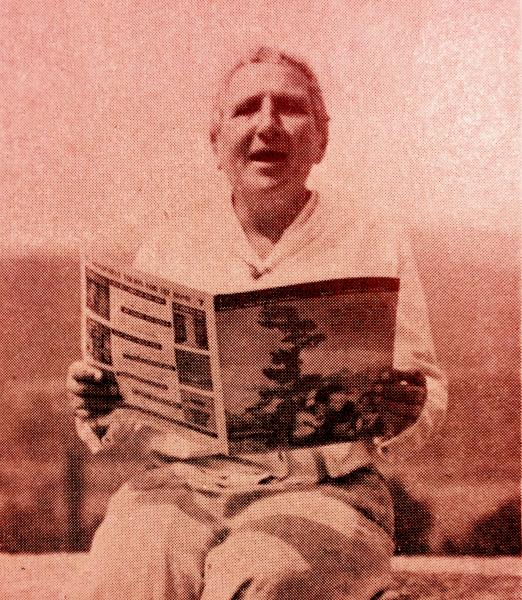

Rogers went on to write a biography of Carl Sandburg and a book about Francis Steloff and the Gotham Book Mart. The front piece of Rogers’s Stein book is his photo of Stein in Bilignin singing Ballard MacDonald and Harry Carroll’s 1913 song, “On the Trail of the Lonesome Pine,” which had been made famous about the time of the photo by Laurel and Hardy in Way Out West (1937):

In the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia,

On the trail of the lonesome pine

In the pale moonshine our hearts entwine

Where she carved her name and I carved mine

Oh, June, like the mountains I’m blue

Like the pine I am lonesome for you

In the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia

On the trail of the lonesome pine.

Jewish Virtual Library:

A Nazi ordinance dated 21 September 1940 forced Jewish [people] of the “occupied zone” to declare themselves as such in police office or sub-prefectures (sous-préfectures). Under the responsibility of André Tulard, head of the Service on Foreign Persons and Jewish Questions at the Prefecture of Police of Paris, a filing system registering Jewish people was created. […] On 3 October 1940, the Vichy government voluntarily promulgated the first Statute on Jews, which created a special, under-class of French Jewish citizens, and enforced, for the first time ever in France, racial segregation. The Statute first made mandatory the yellow badges. The October 1940 Statute also excluded Jews from the administration, the armed forces, entertainment, arts, media, and certain professional roles (teachers, lawyers, doctors of medicine, etc.). A Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs (CGQJ, Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives), was created on March 29, 1941. The police also oversaw the confiscation of telephones and TSF (télégraphie sans fil) radios from Jewish homes and enforced a curfew on Jews starting from February 1942. It attentively monitored the Jews who did not respect the prohibition according to which they were not supposed to appear in public places …

As Burns notes in his essay in the dossier: “naturalized French citizens found that their naturalization could be revoked by a law passed in Vichy in July 1940. The Vichy government was ready to please the Germans, and anti-Semitic propaganda was permitted by a law passed in October 1940. This law defined Jews based on racial criteria, and excluded them from many public service jobs and professions. A law passed in Vichy on October 4, 1940, allowed the French police to arbitrarily arrest ‘any foreigner of the Jewish race.’ At the end of 1940, French officials in the Occupied Zone took a census of Jews — the following year Jews in the Free Zone were subjected to the same census — which in essence meant registration. The mass arrest of Jews was started in May 1941, and in August 1941 a major round-up of foreign Jews took place in Paris.”

According to Mitchell G. Bard’s 1994 study, Forgotten Victims: the Abandonment of Americans in Hitler’s Camps (Westview Press), the US government did not protect Americans, including POWs who were captured by the Nazis, even though it knew that anti-Jewish laws were applied to all Jews in the places they occupied.

US officials took the position that Americans who, in their eyes, missed the boat home were on their own. But this view was to have tragic consequences. Few people in places like France could imagine in 1939 or 1940 what would happen two or three years later. In the case of Americans especially, the thought that they, US citizens, would not be protected must have seemed unimaginable. In fact, it was unimaginable to State Department officials. At the beginning of 1941, for example, Secretary of State Cordell Hull said the Department had learned anti-Jewish laws were being imposed in France, but he expected Americans to be exempted. A couple of months later, the US Ambassador to France informed Hull he was mistaken. The Germans said that measures taken against Jews “do not admit of any exceptions and must be applied to all persons residing in France, regardless of their nationality.” […] [And that] the new laws were instituted to “ensure the recovery of the country.” [Therefore] American Jews would be treated as “liberally as is compatible with the letter and spirit of the laws in question.” (pp. 8–9)

GERTRUDE STEIN AND VICHY: THE OVERLOOKED HISTORY

By Emily Greenhouse in the New Yorker, May 4, 2012 (excerpt, full article linked above):

In 1941, at Faÿ’s suggestion, Stein agreed to translate a set of speeches by Marshal Philippe Pétain — a hundred eighty pages of explicitly anti-Semitic tirades — into English. (She hoped that they would be published in America, although they never were.)

In 1941, at Faÿ’s suggestion, Stein agreed to translate a set of speeches by Marshal Philippe Pétain — a hundred eighty pages of explicitly anti-Semitic tirades — into English. (She hoped that they would be published in America, although they never were.)

I spoke to Barbara Will on Wednesday about the Met’s omission of Stein’s wartime collaboration. […] But enough people pointed out the exhibition’s exclusion of these crucial facts that several officials, including Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer and New York State Assemblyman Dov Hikind, requested that Stein’s collaborationist activities be addressed as part of the exhibition. The Met agreed on Wednesday to add a few sentences to the text on the wall, and to direct patrons to Barbara Will’s Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma,” published last fall […] Stein was never prosecuted for her collaboration with the Vichy government, and her pro-Fascist ideology is often forgotten by those who hail her as a daring cultural progressive. [Emphasis added.]

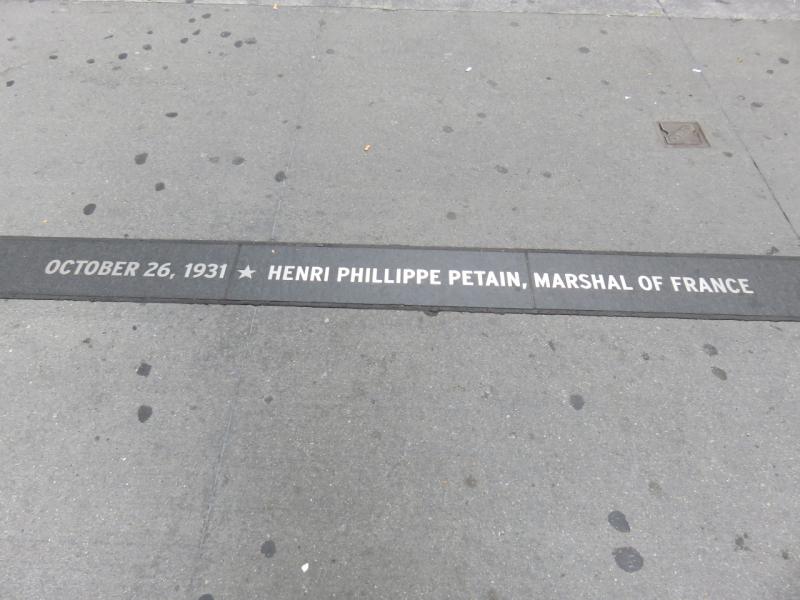

Emily Greenhouse, whose article is excerpted above, is the managing editor of the New Yorker, a publication that prides itself on its fact checking. (In 2019, she was appointed co-editor of the New York Review of Books.) While demanding that Stein’s connection of Pétain be highlighted, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer (later New York City Controller) made no such demand about Manhattan’s government-sponsored “Canyon of Heroes,” featuring those given ticker tape parades, which has a granite-marker honoring Pétain.

Emily Greenhouse, whose article is excerpted above, is the managing editor of the New Yorker, a publication that prides itself on its fact checking. (In 2019, she was appointed co-editor of the New York Review of Books.) While demanding that Stein’s connection of Pétain be highlighted, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer (later New York City Controller) made no such demand about Manhattan’s government-sponsored “Canyon of Heroes,” featuring those given ticker tape parades, which has a granite-marker honoring Pétain.

Vaclav Paris in Jacket2:

Will writes: “Stein translated some thirty-two of Pétain’s speeches into English, including those that announced Vichy policy barring Jews and other ‘foreign elements’ from positions of power in the public sphere and those that called for a ‘hopeful’ reconciliation with Nazi forces.”

[Paris comments on this passage of Will:]

From this report, the reader might assume that Stein’s translations involved writing out in English the anti-Semitic and xenophobic portions of Pétain’s new policies. Certainly Stein did translate Pétain’s declarations of support for Adolf Hitler, and his injunctions to the French to collaborate with the Nazis. However, Stein did not translate any specific reference to Jews. This is not because of her selection, but for the simple reason that there are no such references in Pétain’s speeches. […] Pétain was remarkably silent on the “Jewish question” in his public pronouncements — a fact which, perhaps, can be explained by suggesting that Pétain wanted his speeches to emphasize national unity and solidity.

It sometimes seems to me that Stein’s wartime actions are judged as if Stein were living in Brooklyn during the war. If that were the case, then the accusations — How could she have done what she did? — “What did she know and when did she know it?” — would certainly have a different weight. During the war, Stein and Toklas left Paris and were living in Vichy-controlled France.

It sometimes seems to me that Stein’s wartime actions are judged as if Stein were living in Brooklyn during the war. If that were the case, then the accusations — How could she have done what she did? — “What did she know and when did she know it?” — would certainly have a different weight. During the war, Stein and Toklas left Paris and were living in Vichy-controlled France.

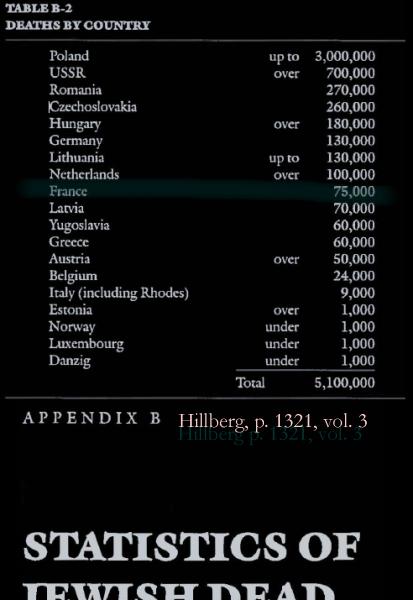

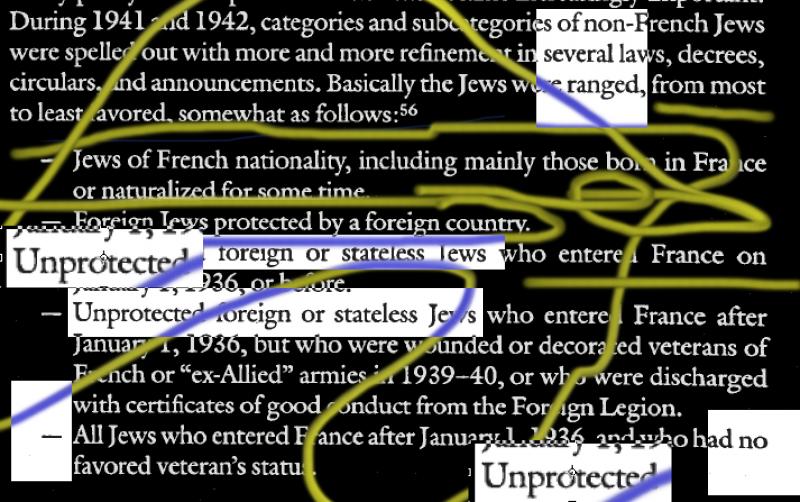

Some people assume that internationally prominent or wealthy Jews with American citizenship who were living in France were relatively safe. Stein’s willingness to make the appearance of translating Pétain’s speeches is cast as a free and enthusiastic expression of her political views. Maybe it was. But no Jews were safe in France during the war. Certainly wealthy, prominent American nationals were safer than stateless Jews and Jewish refugees in France. Raul Hilberg notes that “Jews of French Nationality” were favored over “Foreign Jews protected by a foreign country” who were favored over “unprotected foreign or stateless Jews.” There was a prioritized list (see directly below from Hilberg, vol. 2, p. 664). Then again, Stein might have emigrated to America, but having lived her adult life in France … she preferred not to. France was her home. In 1940, Stein was sixty-six and Toklas just a few years younger. If they considered fleeing France, they may have felt that making a new life in America was not an option. W. G. Rogers, who urged Stein to flee to America, as did the American consul in Lyon, gives a stronger explanation: “The truth was that they refused to desert in time of trouble the adopted land where they were so happy on days of fair weather. Having stuck it out in 1914–1918, they would do it again.” But not without fear. She writes to Rogers: “… and then sometimes about 10 o’clock in the evening I get scared about everything and then I complete[ly] upset Alice and she goes to bed scared …” (p. 191).

Then again, if the Germans had won the war, survival of the remaining Jews in France would have been unlikely. As for American Jews in France, they would become a potential bargaining asset to the victorious Germans.

Apart from Stein’s concern for her own survival, I sometimes imagine her concern for the survival of Alice B. Toklas. I wonder what I would do to protect the ones I love most? I don’t feel I am in any position to judge Stein’s actions during the war. And I don’t think that those actions, whatever they were, and whatever the motivations, both of which we don’t know, need to affect my appreciation for her art.

Gertrude Stein died on July 27, 1946, fifteen months after VE Day. She was seventy-two. Rogers says the toll of the Vichy years shortened her life. Just before she died, Stein appointed Carl Van Vechten her literary executor. From 1936 to 1953, Van Vechten lived at 101 Central Park West on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. In 1950, the year I was born, my family moved to this same apartment building. In 1951, Two: Gertrude Stein and her brother, and other early portraits, 1908–12, edited by Van Vechten, the first volume of the Unpublished Writings of Gertrude Stein was published by Yale University Press, with a foreword by the New Yorker’s Paris correspondent Janel Flanner.

Alice Toklas died in 1967 at age eighty-nine, “staying on alone” (as she put it), without her lover and protector. The lack of legal recognition for Toklas’s relationship to Stein ultimately resulted in the confiscation of her valuable art collection. As a result, Toklas was penniless in her last few years. She survived through the kindness of friends and despite the best efforts of an unscrupulous, and apparently homophobic, Baltimore lawyer named — it’s macabre — Edgar Allan Poe, as Flanner explains in a Dec. 15, 1972 New Yorker article on Toklas, “Memory Is All” (pp. 141–154):

Cecil Beaton, mid-1930s.

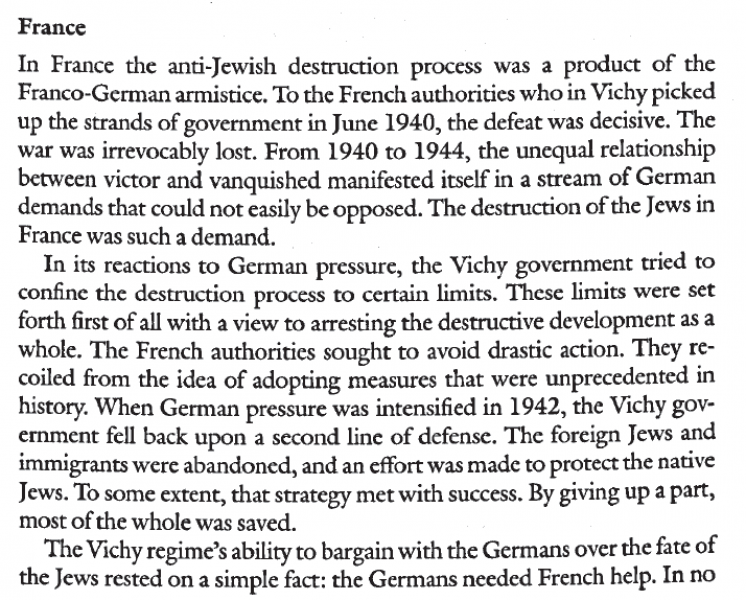

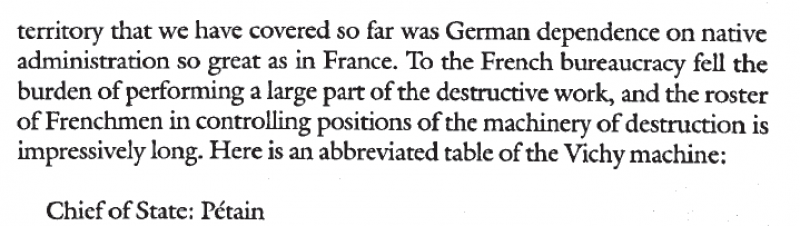

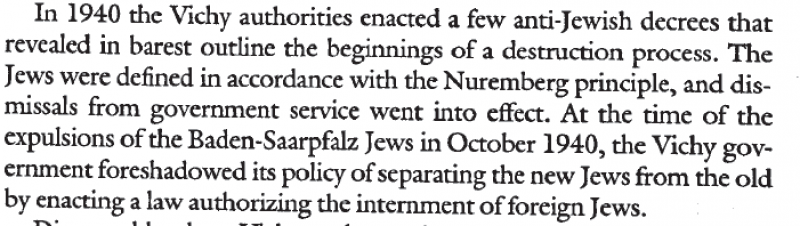

from Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, vol. 2 (Yale University Press, third edn., 2003) “8. Deportations/France,” pp. 645–702. Note: “Foreign Jews” in the passage below refers to “stateless” Jewish refugees and immigrants in France:

:

Hilberg notes that in the early 1940, France was “arraying itself increasingly with the Germans against the Jewish community, fostering an anti-Jewish climate, issuing anti-Jewish laws, and establishing an anti-Jewish regime” (p. 658).

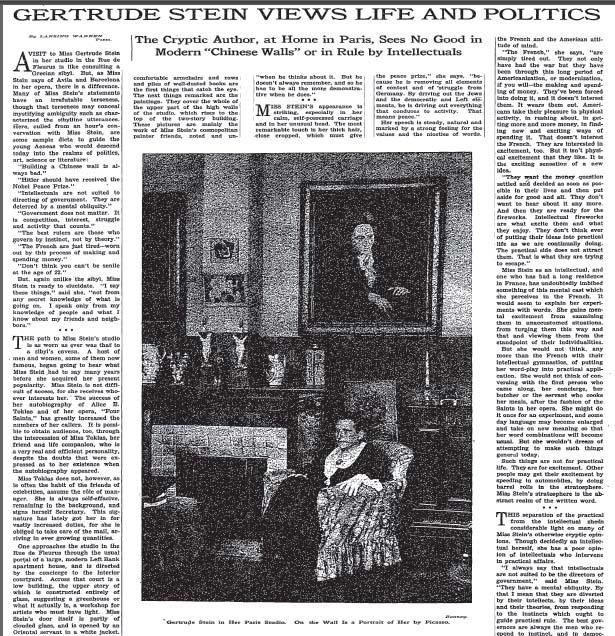

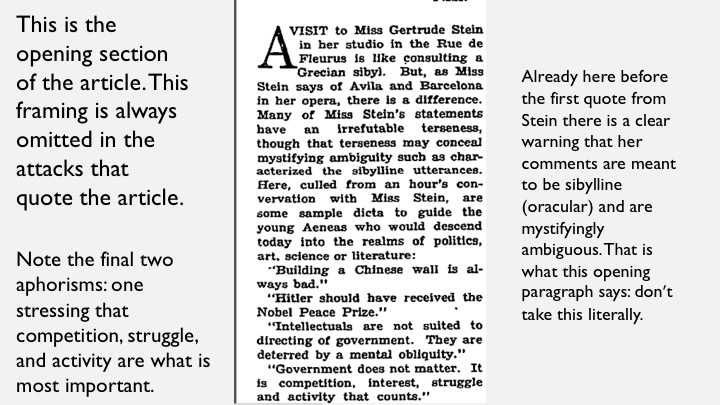

In her National Endowment for the Humanities essay (March/April 2012), Barbara Will writes: “Others have tried to ignore or justify equally inexplicable events: for example, Stein’s endorsement of Adolf Hitler for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934, or her performance of the Hitler salute at his bunker in Berchtesgaden after the Allied victory in 1945.”

In her National Endowment for the Humanities essay (March/April 2012), Barbara Will writes: “Others have tried to ignore or justify equally inexplicable events: for example, Stein’s endorsement of Adolf Hitler for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934, or her performance of the Hitler salute at his bunker in Berchtesgaden after the Allied victory in 1945.”

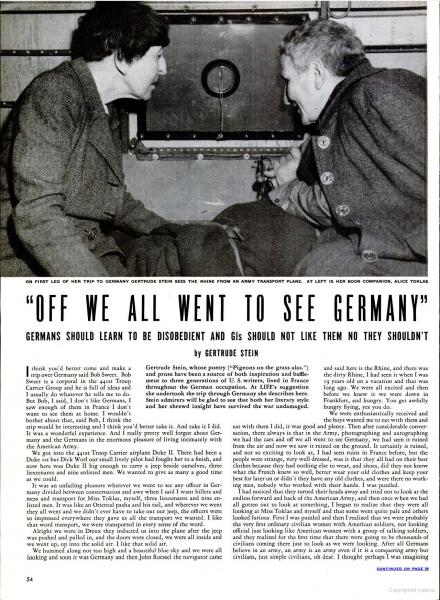

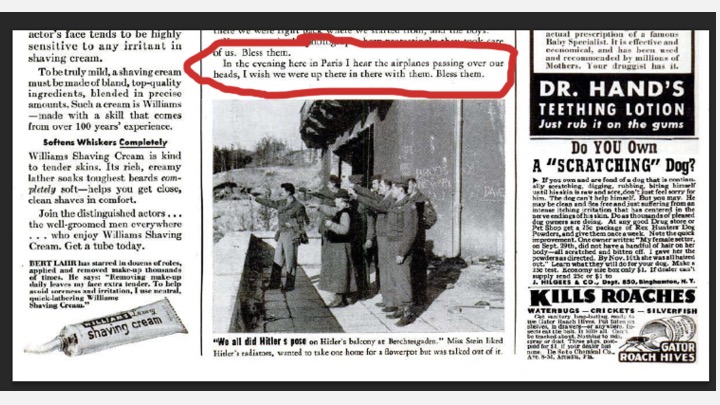

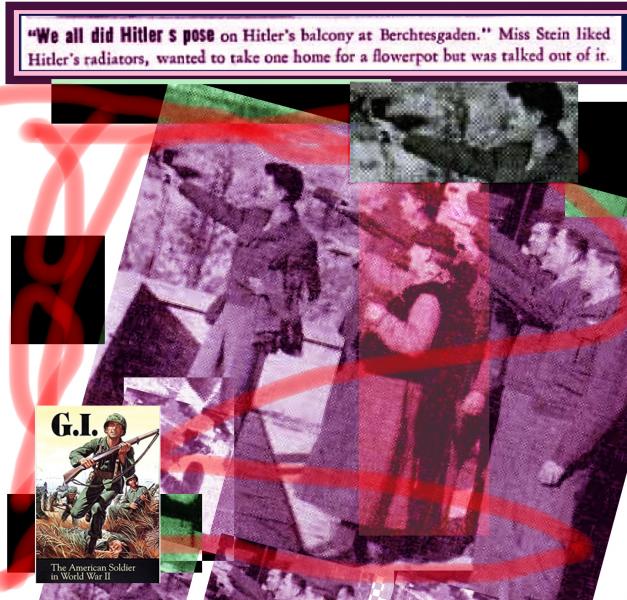

I respond to these false claims in “Gertrude Stein taunts Hitler in 1934 and 1945: Sieg heil, sieg heil, right in der Fuehrer’s face,” my essay in the dossier, so I won’t entirely repeat what I say there, but just restate some key points. Stein’s “Hitler salute” refers to the August 6, 1945 issue of Life magazine, which featured an essay by Stein called “‘Off We All Went to See Germany’: Germans Should Learn to Be Disobedient and GIs Should Not Like Them No They Shouldn’t.” Stein’s essay appears along with a photo-spread of Stein and Toklas. The photo referred to by Will appears on p. 46 of the issue, with a caption, “We all did Hitler’s Pose on Hitler’s Balcony at Berchtesgaden. Miss Stein liked Hitler’s radiators, wanted to take one home as a flowerpot but was talked out of it.”

According to the caption, she and six GIs are mocking Hitler and his gang saluting on the step of Berchtesgaden. But if Stein is indeed pledging her allegiance to the Fuhrer in this picture, as Will suggests, that would also go for the five GIs making the same gesture as she is. And it would mean Life magazine was publishing a picture of pro-Nazi GIs at the moment of liberation in 1945. When Will says that Stein’s motives in this picture are suspect, she is also casting aspersions on Life and the American soldiers that liberated Germany from fascism. In this photo, Stein appears to be illustrating the point made in the subtitle of the Life spread: “Germans Should Learn to Be Disobedient and GIs Should Not Like Them No They Shouldn’t.” (We’ll leave aside the fact the Stein and the GIs seem to be pointing to the field rather than saluting.)

According to the caption, she and six GIs are mocking Hitler and his gang saluting on the step of Berchtesgaden. But if Stein is indeed pledging her allegiance to the Fuhrer in this picture, as Will suggests, that would also go for the five GIs making the same gesture as she is. And it would mean Life magazine was publishing a picture of pro-Nazi GIs at the moment of liberation in 1945. When Will says that Stein’s motives in this picture are suspect, she is also casting aspersions on Life and the American soldiers that liberated Germany from fascism. In this photo, Stein appears to be illustrating the point made in the subtitle of the Life spread: “Germans Should Learn to Be Disobedient and GIs Should Not Like Them No They Shouldn’t.” (We’ll leave aside the fact the Stein and the GIs seem to be pointing to the field rather than saluting.)

What would Barbara Will say about these GIs?

What’s behind the false accusation that Gertrude Stein nominated Adolf Hitler for the Nobel Prize in 1938? Who is behind the use of this disinformation (or fake news) to discredit her and her writing?

I want to summarize the origins and dissemination of the false accusation that Gertrude Stein actively nominated Hitler for the Nobel Prize in 1938.

We have been over this before, but it requires saying again. In my essay in the Jacket2 Stein dossier, I note that Edward Burns reports that the Nobel Prize Committee has denied that any such recommendation was made. See also p. 414 of the Burns/Dydo appendix to the Stein/Wilder letters:

See, for example, the accusation that Stein in 1938, with other intellectuals, proposed Hitler for the Nobel Peace Prize, used in 1995 to underscore Jews’ failing to support their own interests, in Nativ, an Israeli journal of politics and the arts for September 1995, 67–68, and quoted in the English language edition of the Forward, 2 February 1996, 1, 4. This information has been denied by the office of the Nobel Peace Prize Committee in Oslo. Also, on 31 January 1937, Hitler had decreed that no German could ever receive the Nobel Prize in any category.

The Nobel Prize website conclusively refutes the claim that Gertrude Stein nominated Hitler for the Nobel prize in 1938 (or any time). The Nobel Prize website maintains a Nomination database of all nominators and nominees for the prize though 1956. There are no matches on any nominations by Gertrude Stein.

Indeed there was only one nomination of Hitler for the Nobel Prize, by E.G.C. Brandt in 1939, which, according to the Nobel Prize website, was withdrawn the same year. Moreover, the issue of Hitler’s nomination is addressed by the Nobel Prize committee on a page called “Shortfacts”:

Adolf Hitler was nominated once in 1939. Incredulous though it may seem today, the Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1939, by a member of the Swedish parliament, an E.G.C. Brandt. Apparently though, Brandt never intended the nomination to be taken seriously. Brandt was to all intents and purposes a dedicated antifascist, and had intended this nomination more as a satiric criticism of the current political debate in Sweden. (At the time, a number of Swedish parliamentarians had nominated then British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain for the Nobel Peace Prize, a nomination which Brandt viewed with great skepticism. ) However, Brandt’s satirical intentions were not well received at all and the nomination was swiftly withdrawn in a letter dated 1 February 1939.

In addition, in an email to me (5/11/12), Burns notes: “Again, on the charge that she solicited signatures — there is no evidence in the archive at Yale to support such a statement.”

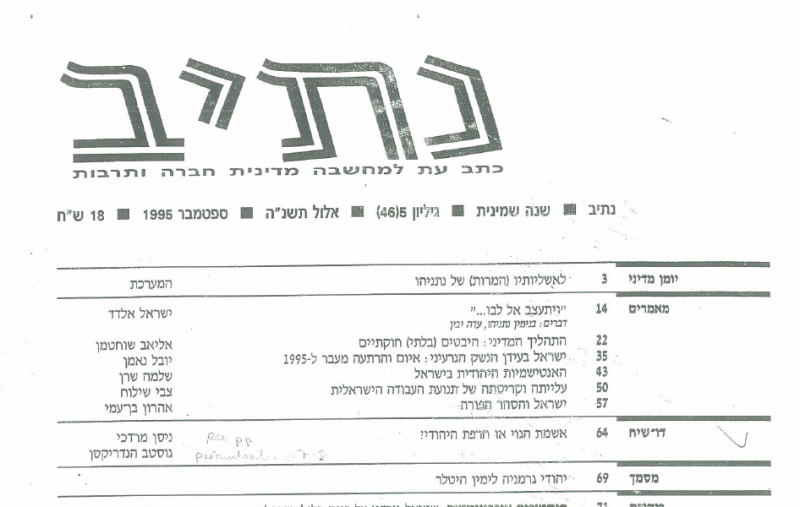

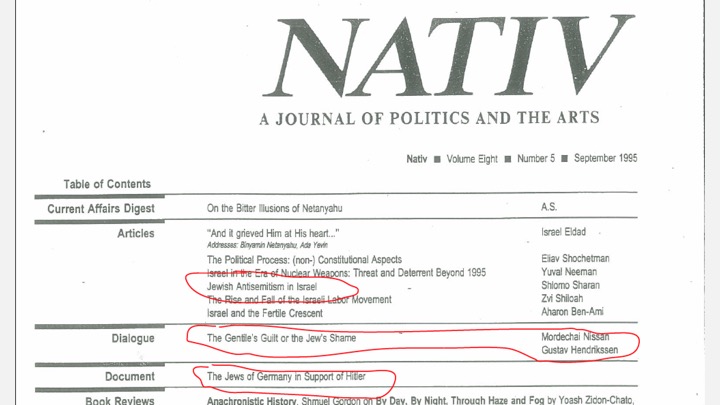

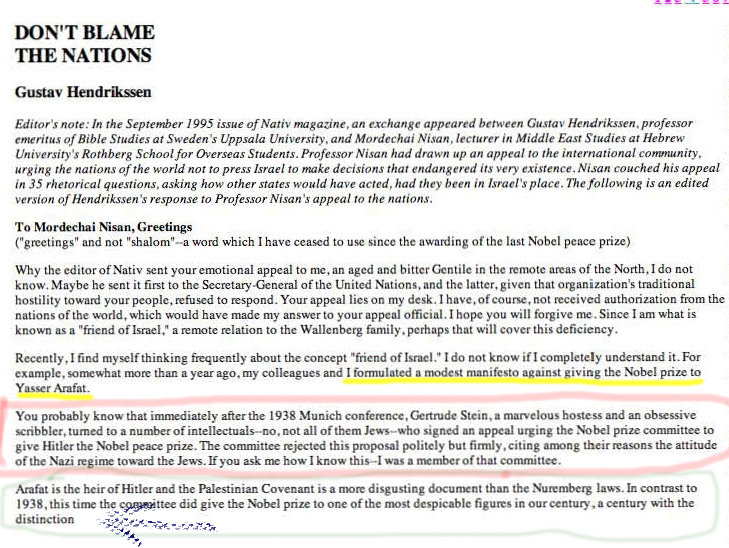

Nativ/Outpost

As Burns discovered, the source of the false report that in 1938 Stein nominated Hitler for the Nobel Peace Prize comes from a claim by Gustav Hendrikssen in “Dialogue: The Gentile’s Guilt or the Jew’s Shame: a Conversation between Mordechai Nissan and Gustav Hendrikssen” in Nativ: A Journal of Politics and The Arts, Volume 8, No 5, September 1995. This is the article that later became the source for an article in the Forward.

All the articles in Nativ are in Hebrew but there is an English table of contents (p. 2) and an English translation that appears later in Outpost. The context of this article, in the overall issue of the magazine, is the rebuke of Jews for being insufficiently supportive of Israel: for example, “Jewish Antisemitism in Israel” and the “document” that immediately follows the Hendrikssen piece, “The Jews of Germany in Support of Hitler.” Nativ is published by Ariel Center for Policy Research (ACPR), a right-wing Israeli organization. Arieh Stav is the editor of Nativ, as he was in 1995. Mordechai Nisan is a professor at Hebrew University, Jerusalem and a “contributing expert” at ACPR; in the Nativ but not the Outpost article his name is spelled Nissan; ACPR gives his actual name, Nisan. This “alternate” spelling is a tip off to the alternate facts in display here.

All the articles in Nativ are in Hebrew but there is an English table of contents (p. 2) and an English translation that appears later in Outpost. The context of this article, in the overall issue of the magazine, is the rebuke of Jews for being insufficiently supportive of Israel: for example, “Jewish Antisemitism in Israel” and the “document” that immediately follows the Hendrikssen piece, “The Jews of Germany in Support of Hitler.” Nativ is published by Ariel Center for Policy Research (ACPR), a right-wing Israeli organization. Arieh Stav is the editor of Nativ, as he was in 1995. Mordechai Nisan is a professor at Hebrew University, Jerusalem and a “contributing expert” at ACPR; in the Nativ but not the Outpost article his name is spelled Nissan; ACPR gives his actual name, Nisan. This “alternate” spelling is a tip off to the alternate facts in display here.

I asked Ariel Resnikoff, a poet, translator, and graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, to summarize the contents of the Hebrew article in terms of Israeli politics. Here is his report:

The Sep. ’95 Nativ article entitled “Dialogue: The Gentile’s Guilt or the Jew’s Shame” is made up of two distinct sections: The first section (“The Gentile’s Guilt”) is written by Prof. Mordechai Nisan as an appeal to the international community, enjoining “the nations of the world” to cut Israel some slack by not asking that it make diplomatic choices that could endanger its existence (i.e. as related to the Palestinians & neighboring Arab States); the meat of the appeal is made up of 35 rhetorical questions that ask how other States would act under pressure if put in Israel’s shoes.

The second section (“Or the Jew’s Guilt”) is allegedly written by Gustav Hendrikssen as a letter to Nisan, which says that it is in fact the secular liberal Jews (Rabin, Peres, & then, of course, Stein as a bizarre precursor) who are making the choices that will lead to the destruction of Israel & the Jewish People (this in response to the ’94 Nobel Peace Prize split between Rabin, Peres & Arafat).

I read the Hebrew side of all this as as an ugly, ignorant hoax, which aims to frame Jews who supported the Two State Solution as traitorous anti-Semites (like Stein) & serious threats to the security of the Jewish State. This type of rhetoric has, unfortunately, become a norm in political discourse today in Israel & is only getting worse …

As I was translating the Gustav Hendrikssen letter entitled “… Or The Jews Shame” (framed as a response to Mordechai Nisan’s essay, “The Jew’s Guilt,”) from the Sept. 1995 issue of Nativ, I noticed that it is in fact the very same text that the editors of Outpost published just two months later as “Don’t Blame the Nations” in their Nov ’95 issue. So the translation is there in Outpost, in its entirety, & tho it’s not a great translation (probably done by one of the eds at Outpost), it gets the job done in terms of what you’re looking for, I think. It’s an ugly letter, to say the least, & even more so since it is so very obviously fabricated … because it is pretty much unthinkable that an elderly Swedish Christian theologian would’ve been able to read [Nisan’s original Hebrew essay], let alone write [a response] in modern Hebrew! & if he wrote the letter in Swedish, what right-wing Israeli editor at Nativ wdv’e been able to translate it? There is no attribution of translation, or reference to what language Hendrikssen’s letter was originally written in, which just makes the whole thing even more absurd …

Gustav Hendrikssen — who the Forward reports as being “a conservative Christian theologian” in his late eighties and living in a nursing home at the time of the Nativ article — repeated the same charge — that Stein nominated Hitler for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1938 — the following month, in an article Resnikoff mentions, entitled “Don’t Blame the Nations,” published in the November 1995 issue of Outpost, the newsletter of Americans for a Safe Israel. Americans for a Safe Israel is described by Wiki as opposed to “all territorial withdrawals by Israel. It supports the Israeli settlement movement and campaigned against the Oslo Accords and the evacuation of settlers from Gaza.”

In the Outpost article, Hendrikssen claims that he was a member of the Nobel Peace Prize Committee in 1938 (p. 4). The Nobel Peace Prize website gives a full list of every member of the committee, and it shows, definitively, that Hendrikksen was never a member of the committee. Outpost identifies Hendrikssen as “professor emeritus of Bible Studies at Sweden’s Uppsala University” (p. 4). In the article he describes himself as “a Christian who has managed to divest himself from hatred of Jews (a difficult undertaking but not impossible)” for whom “Israel was a divine message” (p. 4).

The 1994 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded jointly to Arafat, Shimon Peres, and Yitzhak Rabin. This is the context for Hendrikssen’s charge that self-hating Jews like Peres, Rabin — and Stein! — are to blame for the fact that Yassir Arafat was awarded the prize. But it does not stop there. This “aged and bitter Gentile in the remote areas of the North” (p. 4) ends his article with a chilling condemnation of “Satanic” Jews, who, like Stein and Rabin, and me, do not share his Christian evangelical Zionism. He calls us “simpletons” afflicted with “spiritual AIDS”:

The Jewish soul you have already sold to the devil. Now you are busy tearing up the body, or more correctly, what has been left of it. Already, you prepare for exile. In a grotesque distortion, with your own hand you print the mark of Cain on your brow — not for having murdered your brother, but because he has murdered you. The voice of your blood, not the voice of his, is what cries from the ground. Is there a more satanic and truer expression of Hegel’s statement, “The tragedy of the Jewish people does not inspire in me fear and pity, but a very deep revulsion” ... ?

In my frequent visits to Israel, I noticed a profound deficit that distinguished the Hebrew nation — a deficit of straightforward simplemindedness. I refer to those diligent, straightforward simpletons who are the mainstay of a well-ordered nation, behind the barricades of which the land guards its soul from the spiritual AIDS of the “world improvers.” I have not found this aristocracy of simple folk in your land and it is a great defect that cannot be remedied. On the contrary, with every step you find “the creative genius,” whose hand is in everything, from the stockmarket to the PLO, selling shares in the morning and his homeland in the afternoon, and in the evening, if he has any strength left, he girds his loins and sallies forth to defend the rights of those who want to annihilate him.

Therefore, my friend, do not address your sad call to the nations of the world, or its Creator. The guilt lies not with them. This time, for a change, their hands are clean. Send a letter to your own people. Compose a letter to the simpletons, those whom Erasmus extolled in his In Praise of Folly. Go and find them in the markets, in the buses, in the stores, in all the places where their instinct for survival has not yet been extinguished. Just be sure to stay away from the universities.

The Forward (venerable Jewish weekly)

Three Forward articles are commonly cited in reference to Hendrikssen’s comments in Nativ about Stein and the Nobel. Hendrikssen’s Outpost article has never been cited, insofar as far I have been able to determine.

The only significant reference to Hendrikssen’s Nativ article is in the Feb. 2, 1996 issue of the Forward, “How Gertrude Stein Sought Nobel Prize for Hitler” by Jonathan Mahler (Vol. LXXXXXVIII, Issue 3106; p. 1). There are two anomalies in this article. First, Mahler spells Hendrikssen’s name Hendrikksen (both Nativ and Outpost spell it Hendrikssen, but he is listed in this way on an ARIEL document). Second, Mahler’s title is the same as in the unreferenced, English language article, in Outpost. The title of the Nativ piece is “Dialogue: The Gentile’s Guilt or the Jew’s Shame.” The fact that the 1995 Outpost article title is given, and that the name is misspelled, suggests, at best, that Mahler had not seen the Outpost or Nativ pieces but relied for his story solely on the work of Nativ’s editor, Arieh Stav, whom he quotes.

NEW YORK — Buried inside a recent issue of a right-wing Israeli magazine is a nugget that may send some left-wing heads spinning — Gertrude Stein, queen of American expatriates in Paris, spearheaded a 1938 campaign urging the Nobel committee to award its peace prize to Adolf Hitler. This was disclosed by Gustav Hendrikksen [sic], professor emeritus of Bible studies at Sweden’s Uppsala University and a former member of the Nobel committee, in Nativ, a political magazine published in Israel. Mr. Hendrikksen’s article, “Don’t Blame the Nations,” argues that Israel committed a catastrophic mistake by negotiating with the Palestinians and deals harshly with the Nobel committee’s decision to award the Peace Prize to Prime Minister Rabin, Foreign Minister Peres and the chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, Yasser Arafat. […] Even though Mr. Hendrikksen doesn’t offer any written proof, his assertions about Stein are adding a new wrinkle to the understanding of this German-Jewish writer and art collector […] According to Mr. Hendrikksen, who is now in his late eighties and lives in a nursing home in Sweden, the Nobel committee rejected Stein’s proposal “politely but firmly, citing among their reasons the attitude of the Nazi regime toward the Jews.” In Nativ, Mr. Hendrikksen, chides Israel for surrendering land to the Palestinians. A conservative Christian theologian and an avowed friend of Israel, Mr. Hendrikksen refers to the late prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, and the current premier, Shimon Peres, as Stein’s “spiritual heirs” for their role in helping Yasser Arafat win the Nobel Peace Prize.

To its credit, Mahler, who strikingly calls Stein “German-Jewish,” then prints “contradictory evidence”:

Despite her ties to Fay, there is evidence she was active in the French Resistance, offering her home as a refuge for travelers during the German occupation. Indeed, a statue in the south of France commemorating the resistance mentions her by name. Moreover, the villain in her novel “Mrs. Reynolds,” Angel Harper, was modeled after Hitler (note the identical initials). In 1943, Stein began writing “Wars I Have Seen,” an autobiography in which she addresses the effects of the Nazis occupation of her adopted country.

Despite this disclaimer, of sorts, Mahler’s article has legitimated malicious accusations against Stein. And he is not now willing to offer any explanation for the discrepancies in his article. Mahler, who is now associated with The New York Times Magazine, did not answer email requests for comment.

On June 14, 1996, the Forward published another article on this topic by Rachel Shteir, “Replaying Gertrude Stein’s Expatriate Games” (p. 15). No new facts are provided, only a reference to Mahler’s Feb. 2, 1996 article. I find nothing at all about Stein in the Forward of Oct. 25, 1996 (as claimed by Mark Weber, see below).

Mahler’s Forward article states that Hendrikksen [sic] has his information on the Peace Prize since he is “a former member of the Nobel committee.” As noted above, the Nobel Peace Prize website gives a full list of every member of the committee (link here) and it proves that Hendrikssen (under either spelling) was never a member of the committee.

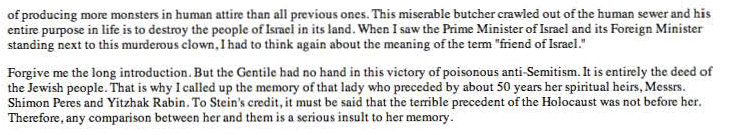

Who is Hendrikssen? Leaving aside the fact that the Nobel Peace Prize is Norwegian and not Swedish, perhaps a tip-off to the hoax, the LIBRIS database (titles held by Swedish university and research libraries) gives no record of anything written by him (for either spelling). Worldcat has no citation of any kind with that last name.  A Google search produces only the English references discussed in here; there is not a single Swedish reference to him. A more likely spelling for a Swedish name would be Hendriksson or Hendrikson. Finally, Cecilia Wejryd, Assistant Dean the Department of Theology at Uppsala University writes:

A Google search produces only the English references discussed in here; there is not a single Swedish reference to him. A more likely spelling for a Swedish name would be Hendriksson or Hendrikson. Finally, Cecilia Wejryd, Assistant Dean the Department of Theology at Uppsala University writes:

“The faculty of Theology has never had a professor named Gustav Hendrikssen. We have never heard of him and there are no publications in his name in our library.”

Email reproduced with the permission of Cecilia Wejryd (2017)

Who has broadcast the false 1938 Nobel nomination story?

The rather transparent hoax has its origin in two extremely hawkish Zionist publications, one in New York and one in Israel. The subsequent broadcast of the story has included the strange bedfellows of American neo-Nazi sites, along with American right-wing sites. Note that many of these articles follow the Forward’s misspelling of Hendrikssen, suggesting that the Feb. 2, 1996 Forward article is the only source.

•Mark Weber, “Gertrude Stein’s Complex Worldview: Nobel Peace Prize for Hitler?” Institute for Historical Review, cited on the website as from Sept.–Oct. 1997 (Vol. 16, No. 5), pp. 22 ff. This piece is a paradigm for the later ones. The source is given as “(Reports about this appeared in the New York Jewish community weekly Forward, Feb. 2, June 14, and Oct. 25, 1996.)” Note the list of the three articles, even though the third does not exist and the second simply an echo of the first; the article misspells Hendrikssen. Wiki describes the Institute for Historical Review in this way:

The Institute for Historical Review (IHR), founded in 1978, is an American organization that describes itself as a “public-interest educational, research and publishing center dedicated to promoting greater public awareness of history.” Critics have accused it of being an antisemitic “pseudo-scholarly body” with links to neo-Nazi organizations, and assert that its primary purpose is to disseminate views denying key facts of Nazism and the genocide of Jews and others. It has been described as the “world’s leading Holocaust denial organization.” The Institute published the non-peer-reviewed Journal of Historical Review until 2002, but now disseminates its materials through its website and via email.

INSTITUTE FOR HISTORICAL REVIEW

Gertrude Stein’s Complex Worldview: Nobel Peace Prize for Hitler?

By Mark Weber, 1997

Scholars of the life of Gertrude Stein were recently startled to learn that in 1938 the prominent Jewish-American writer had spearheaded a campaign urging the Nobel committee to award its Peace Prize to Adolf Hitler. This was disclosed by Gustav Hendrikksen, a former member of the Nobel committee and now professor emeritus of Bible studies at Sweden’s Uppsala University, in Nativ, a political magazine published in Israel. (Reports about this appeared in the New York Jewish community weekly Forward, Feb. 2, June 14, and Oct. 25, 1996.) […] Hendrikksen, an avowed friend of Israel who is now in his late eighties, recalled that the Nobel committee rejected Stein’s proposal “politely but firmly, citing among their reasons the attitude of the Nazi regime toward the Jews.” […]

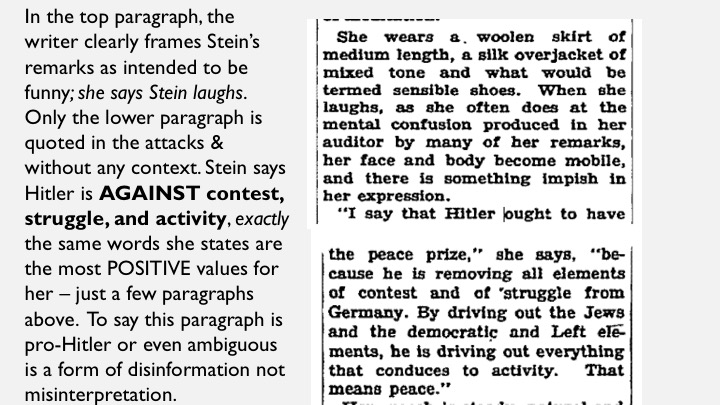

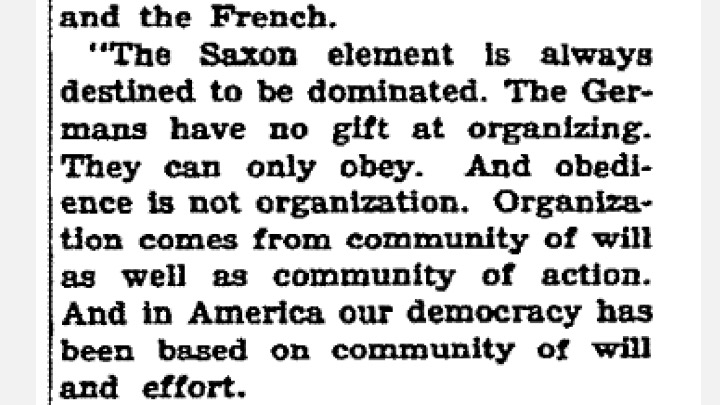

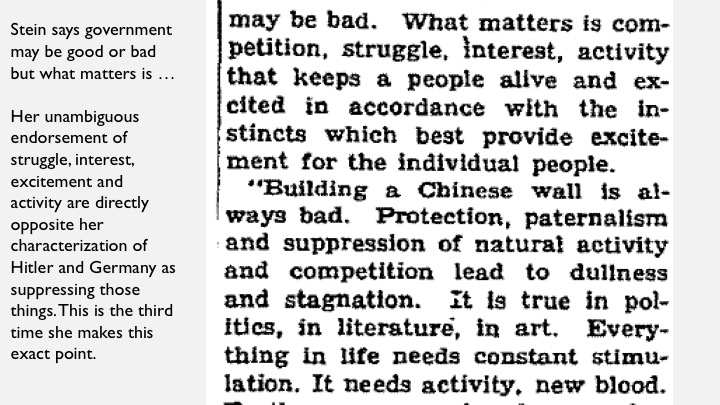

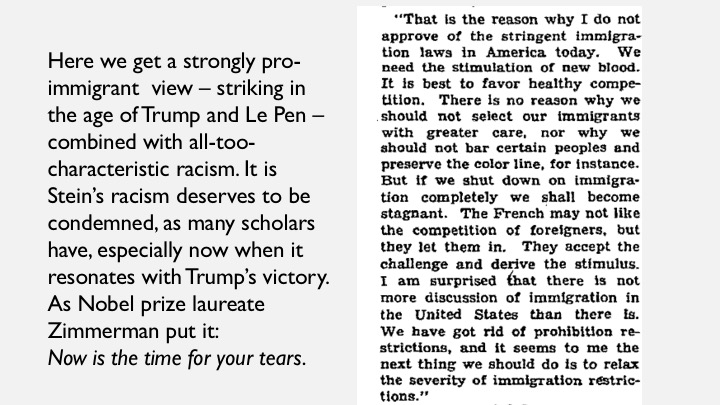

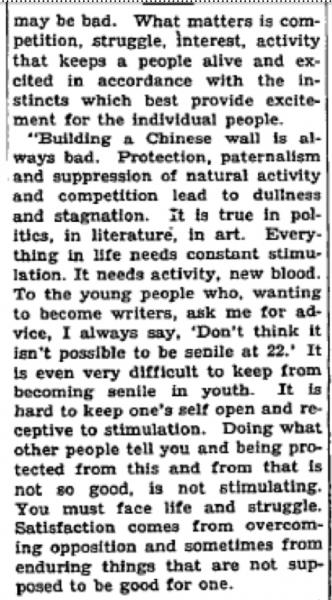

Stein’s seemingly paradoxical views about Hitler and fascism have never been a secret. As early as 1934, she told a reporter that Hitler should be awarded the Nobel peace prize. “I say that Hitler ought to have the peace prize, because he is removing all the elements of contest and of struggle from Germany. By driving out the Jews and the democratic and Left element, he is driving out everything that conduces to activity. That means peace … By suppressing Jews … he was ending struggle in Germany” (New York Times Magazine, May 6, 1934).

As astonishing at it may seem today, in 1938 many credited Hitler for his numerous efforts to secure lasting peace in Europe on the basis of equal rights of nations. After assuming power in 1933, he succeeded in quickly establishing friendly relations with Poland, Italy, Hungary, and several other European nations. Among his numerous initiatives to lessen tensions in Europe, the German leader offered detailed proposals for mutual reductions of armaments by the major powers.

•The story was picked up by Michael Santomauro on Pat Buchanan’s blog, Oct. 10, 2008. (He uses the wrong spelling of Hendrikssen.) The story is sourced as from The Barnes Review. Wiki says of this publication: “The Barnes Review is a bi-monthly magazine founded in 1994 by Willis Carto, dedicated to historical revisionism such as Holocaust denial. Willis Carto had earlier founded the Institute for Historical Review in 1979 but lost control of that organization in an internal takeover by former associates.”

• Phyllis Chesler, “Anti-Anti-Semites Unite,” in David Horowitz’s FrontPageMagazine.com, August 18, 2003. Chesler endorses Hendrikssen’s views in the Nativ article: “Hendrikssen suggests that Jews themselves, especially intellectuals, including those in Israel ‘have lost their instinct for survival.’” Stein, with the false Nobel Prize story repeated, is used as a negative example of this. Chesler republished the article on her own website and it was reprinted at FreePublic.Com, which bills itself as the voice of “grass-roots conservatism”; see Wiki on their campaigns agains the Dixie Chicks and Dan Rather.

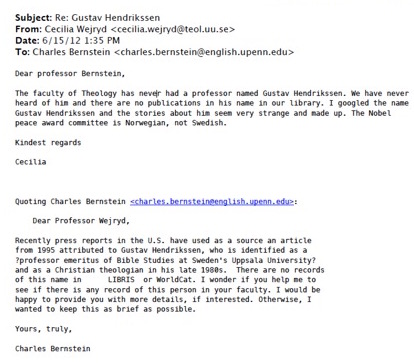

•“Hitler Ought to Have the Peace Prize,” AdolfTheGreat.Com, from Nov. 2007 or earlier. This is echoed on a post from September 2, 2010 from Stormfront, a “White Pride” “White Nationalist” website. Both cite the three Forward references and misspell Hendrikssen’s name.

•“Hitler Ought to Have the Peace Prize,” AdolfTheGreat.Com, from Nov. 2007 or earlier. This is echoed on a post from September 2, 2010 from Stormfront, a “White Pride” “White Nationalist” website. Both cite the three Forward references and misspell Hendrikssen’s name.

•Sonia Melnikova-Raich, “Exhibit leaves out how Gertrude Stein survived Holocaust,” Jewish News of Northern California, June 10, 2011.

•Bill Berkowitz, “Did You Know Gertrude Stein Allegedly Advocated Adolf Hitler for a Nobel Peace Prize? It Gets Worse,” The Buzzflash Blog, Sept. 12, 2011. This article cites the piece in “AdolfTheGreat.Com.” Note this comment after the article from Melnikova-Raich (cited directly above), which gives the telltale wrong spelling of Hendrikssen (the comment is no longer on-line).

•Alexander Nazaryan, “Gertrude Stein exhibit at the Met will now allude to her Hitler-loving past and collaboration with Vichy regime,” New York Daily News, May 7, 2012.

•John Hayward, “White House salutes Nazi sympathizer for Jewish American Heritage Month ‘In error’: The smartest Administration in history screws up again,” Human Events magazine, May 3, 2012. Human Events is a well-known right-wing magazine. The piece foregrounds Alan Dershowitz’s statements and Nazaryan’s Daily News piece. Haywood writes: “It should be noted that according to the Nobel foundation, Hitler’s nomination was intended as ‘a satiric criticism of the current political debate in Sweden’ when it finally came before the committee, and ‘was swiftly withdrawn in a letter dated 1 February 1939.’” Odd in that his piece contradicts the Nazaryan quote and the defamatory argument. Odder still that the Nobel link given in the article refers to the Hitler nomination not by Stein but by E.G.C. Brandt, so flatly contradicting what Haywood is asserting.

• Peter Worthington, “Stein way of life a myth,” Toronto Sun, May 26, 2012. Worthington wrote to me after I pointed out the factual errors in this article but made no correction to his article, in which he writes:

Peter Worthington, “Stein way of life a myth,” Toronto Sun, May 26, 2012. Worthington wrote to me after I pointed out the factual errors in this article but made no correction to his article, in which he writes:

Stein was an admirer of Hitler, and nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize in 1935. She even lobbied for him to get the award in 1938, on grounds that by curbing Jews and opposition in Germany, Hitler ensured a peaceful country.

She despised President Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, and was an admirer and supporter of Franco in Spain. She has been described as a self-hating Jew, with Fascist leanings.

Always an admirer of Marshal Philippe Pétain, France’s hero of WWI, and a Nazi puppet in Vichy France in WWII, Stein dedicated herself to translating 32 of Pétain’s wartime speeches into English for distribution in America.

Although she died from cancer in 1946, she escaped the fate of many Nazi collaborators, even though she helped the Nazis and perhaps betrayed those who resisted the occupation. Her unique art collection was protected.

Her Vichy protector was one Bernard Faÿ, a Harvard-educated, anti-Semitic homosexual, responsible for rounding up Jews to send to German death camps. He was Pétain’s friend and advisor, and he admired Gertrude Stein. After the war he did time in jail as a collaborator and was freed in the amnesty of 1953.

In an article itemizing aspects of Gertrude Stein’s life, writer Mark Karlin notes that the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum advertised five phases of Stein’s life. Karlin wryly suggests a “sixth” phase is missing — her relationship with Nazis.

To him, it verged on the obscene to honour the Stein’s art collection with that of Salomon’s, whom the Nazis gassed because of her work, yet they preserved and protected Gertrude Stein.

When challenged for omitting the pro-Nazi aspects of Stein’s life, the Jewish museum spokesperson said the museum shop sold books (including Barbara Will’s book) that gave unsavory details of her life.

Even the White House stumbled when President Barack Obama recently lauded Jewish Heritage Month (May) by saying “Their history of unbroken perseverance and their belief in tomorrow’s promise offers a lesson not only to Jewish Americans, but to all Americans. From Aaron Copland to Albert Einstein, Gertrude Stein to Justice Louis Brandeis.”

Under prodding by human rights lawyer Alan Dershowitz, the White House later acknowledged that it should not have included Gertrude Stein’s name.

Michael Kimmelman reviews Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice by Janet Malcolm (Yale University Press, 2007) in the Oct. 25, 2007 issue of the New York Review of Books.

Janet Malcolm’s Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice was more widely praised than any other book by or about Stein since the Autobiography of Alice Toklas. Malcolm’s book was initially serialized in The New Yorker, a publication that has taken a strong ideological stand against the kind of poetic innovation associated with Stein. In his review in the New York Review of Books, Michael Kimmelman, a New York Times art and architecture critic echoes Malcolm’s harsh dismissal of Stein’s early masterpiece, The Making of Americans calling it “impenetrable” and quoting Malcolm: “a text of magisterial disorder,” “ponderous and unforgiving, a morass, a nervous breakdown of a novel, swerving between conventional narrative and gibberish … a work that Stein evidently had to get out of her system — almost like a person having to vomit.” Notably, neither Malcolm or Kimmelman have any engagement, or apparent knowlege about, modernist American poetry and they appear to have been chosen by their insitutional sponsors, The New Yorker and New York Review of Booksbecause of their axiomatic rejection of her literary work. The disgust for Stein by Malcolm and Kimmelman is visceral (vomit) and sexual (impenetrable). Kimmelman even suggests that something is amiss in Stein’s sexual relationship to “dark” Alice Toklas, as he calls her. He reports that “Stein gave Toklas orgasms but received none,” in the process misrepresenting the richly evocative account given by Ulla Dydo in The Language Which Rises, pp. 50, 51, 233, 316), which is Malcolm’s source for this quote. In this context, Stein’s relation with homosexual arch-Nazi Bernard Faÿ is an extension of her sexual perversion. As Kimmelman puts it, “The affection for Faÿ therefore becomes part of a larger pathology.” Once again Stein is on her knees, “pleading, like a supplicant,” begging for favors. (Kimmelman credits “pleading, like a supplicant” to what sounds like a bogus and homophobic anecdote of Ernest Hemingway about Stein’s sexual attentions to Toklas; for Kimmelman it has “the ring of truth.”) Yet the dastardly Faÿ was able to get great pleasure from The Making of Americans (for which he wrote an introduction and translated sections) in a way that Malcolm and Kimmelman are incapable of. “For Malcolm,” Kimmelman says, “Stein’s language of equivocation — her evasiveness about the truth — suggests something fundamental about her being, quite aside from her charm and lucidity and ease in private conversations.” For Kimmleman, the faults of Stein the person can be found in Stein’s modernist composition, which is deeply deceptive, a kind of conniving Jewish doubletalk.

The New York Review of Books turned to the reliably hostile-to-Stein Michael Kimmelman for an April 26, 2012, piece called Missionaries, that reviews three books The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde (the catalog for the Met show), Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Fäy, and the Vichy Dilemma by Barbara Will, and Ida: A Novel by Gertrude Stein, edited by Logan Esdale. Note how Kimmelman uses the same decontextualized quote as the right-wing Institute for Historical Review and HitlerTheGreat.Com:

“Hitler should have received the Nobel Peace Prize,” she meanwhile told The New York Times Magazine in 1934, and, alas, she apparently meant it. “He is removing all elements of contest and of struggle from Germany,” she explained. “By driving out the Jews and the democratic and Left elements, he is driving out everything that conduces to activity. That means peace.”

The New York Review of Books, despite their policy of publishing numerous letters — I can recall several on the topic of a possible typo of a single word in Joyce — refused to publish a letter sent to them by Joan Retallack, Edward Burns, and me in which we referred Kimmelman to the source article for his misguided claim that Stein endorsed Hitler for the Nobel Prize. While NYRB wouldn’t print our letter, they did print a letter from Kimmelman in the July 12, 2012 in which he comments his own review. His letter, published under the title “Gertrude Stein & Fascism,” purports to respond to our concerns but declines to give our names. Kimmelman’s letter just adds insult to injury, though I am grateful that it gives a link to our Jacket2 dossier. Evidently Kimmelman prefers what he calls “the ring of truth” to truth. But let’s turn his own condemnation of Stein on him: his “language of equivocation — [his] evasiveness about the truth — suggests something fundamental …” Here is his letter:

To the Editors:

To the Editors:

A number of writers have made some criticisms of my review of “The Steins Collect” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art [NYR, April 26]. I’m glad to make it clear in reply that not all scholars are as troubled as others by Gertrude Stein’s remark that “Hitler should have received the Nobel Peace Prize,” claiming that it was not meant in earnest; and similarly some scholars believe that Stein’s friendship with the Vichy official Bernard Faÿ was no more than a friendship, and not indicative of sympathies on Stein’s part for Vichyites or Nazi collaborators, notwithstanding her translation of Pétain’s speeches and attempts to publish them in America.

The evidence in both cases is arguable. Of course, Stein was not the only major writer of the early twentieth century who read and appreciated the work of Otto Weininger, the Austrian philosopher who wrote Sex and Character, a racist taxonomy of humanity. I am very happy to encourage readers to consult an article cited by some of those Stein scholars who took issue with my characterization.

— Michael Kimmelman, New York City

T.S. Eliot on Gertrude Stein “Charleston Hey Hey”

(Nation & Athenaeum, Jan. 29, 1927)

[Stein’s] work is not improving, it is not amusing, it is not interesting, it is not good for one’s mind. But its rhythms have a peculiar hypnotic power not met with before. It has a kinship with the saxophone. If this is the future, then the future is, as it very likely is, of the barbarians. But this is the future in which we ought not to be interested.

Captain Louis Renault in Casablanca is the iconic figure of the Vichy collaborator in American popular culture. At the end of the film Louis turns against Major Heinrich Strasser, the Nazi, and allies himself with Rick, that is, with the soon-to-be victorious Americans. I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Casablanca was released nationally in the US in early 1943, just as Stein, like Louis, was throwing her Vichy water in the waste basket.