Gil: Talk for launch of Gil Ott's 'arrive on wave'

Presented at Temple University on January 24, 2016

“We / take the form / of our uncertainty,” Gil Ott wrote in a 1984 poem. I take that as a motto of a poetics we shared, Gil and me, born the same year smack in the middle of the last century. Uncertainty remains now, as it was thirty years ago, as it was in 1950, a poetic vice for many. Gil expressed his searching uncertainty with an unflappable and genial defiance, living his fifty-four years with grace, courage, outrage, and élan.

I want to thank Charles Alexander for publishing Gil’s collected poems, arrive on wave, another beautiful edition from Chax press, and also to thank the three editors: Gil’s old friend Eli Goldblatt; Gregory Laynor, who I got to know when we participated in a couple of my seminars at Penn; and Trace Peterson, who first heard about Gil from Charles Alexander. I remember meeting Trace in 2004, when she invited Susan Bee and me to do a talk in her Analogous series in Cambridge, and we’ve stayed friends since. Charles Alexander has published four books of mine; the first, Fool’s Gold, a collaboration with Susan in 1991, created at a residency he arranged for us and our daughter Emma, who has four at the time, in Tucson. I make explicit these relations because they flood to mind when thinking of Gil and because I need to acknowledge, with a tear, the tear Gil’s death made in the intimate fabric of our connections with one another.

I want to thank Charles Alexander for publishing Gil’s collected poems, arrive on wave, another beautiful edition from Chax press, and also to thank the three editors: Gil’s old friend Eli Goldblatt; Gregory Laynor, who I got to know when we participated in a couple of my seminars at Penn; and Trace Peterson, who first heard about Gil from Charles Alexander. I remember meeting Trace in 2004, when she invited Susan Bee and me to do a talk in her Analogous series in Cambridge, and we’ve stayed friends since. Charles Alexander has published four books of mine; the first, Fool’s Gold, a collaboration with Susan in 1991, created at a residency he arranged for us and our daughter Emma, who has four at the time, in Tucson. I make explicit these relations because they flood to mind when thinking of Gil and because I need to acknowledge, with a tear, the tear Gil’s death made in the intimate fabric of our connections with one another.

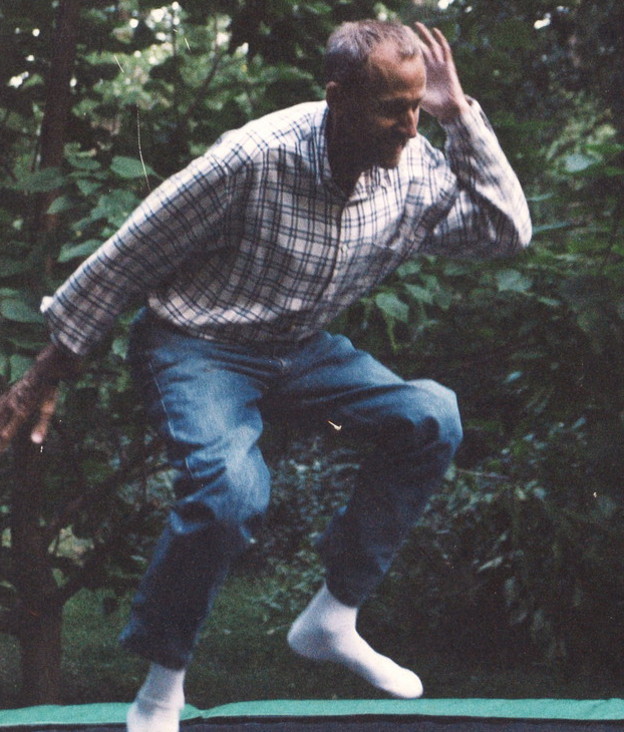

The eidetic memory I have of Gil is his meeting me at 30th Street Station in Philadelphia before a reading he set up at the Painted Bride. That might have been the first time I was in that station, but most times since then I think of Gil coming toward me through that long, great hall, as I came up the stairs from the tracks. Maybe it’s because I associate Gil with Walker Hancock’s World War II memorial in the station.

My first memory of Gil is his walking down Spring Street in New York in the late 1970s, going east from the Ear Inn, in the year or so after an unsuccessful transplant. I remember how slow he walked, how cumbersome and heavy his body seemed. And how, just a year later, he came into a new life and new sense of physical and cultural possibility, after his first successful transplant.

I remember Gil Ott’s magazine, Paper Air, which he started in 1976 and continued, in four volumes, for fourteen years. Paper Air is available in digital form at Craig Dworkin’s Eclipse. In his preface to the first issue, Gil calls for “revolutionary perception,” and speaks of poets as “technicians of the imagination” (echoing Jerome Rothenberg’s Technicians of the Sacred). Appearing in the magazine’s first volume were Toby Olson, Nathaniel Tarn and Janet Rodney, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, and Ron Silliman. The second volume, in 1977, opened with the notable John Taggart issue and included Jackson Mac Low’s light poem for John and John’s scolding remarks about Ron and Clark Coolidge, which Ron graciously replies to in the next issue. That issue also featured Eli Goldblatt on Oppen.

I first appeared in the 1979 issue with poems from Stigma. Gil took a few years out from the magazine but came back in style with the crucial 1980 Jackson Mac Low issue (2:3). Volume three’s first issues focused on contemporary French poetry but also had poems of mine and Douglas Messerli’s review of Controlling Interests. This was the time Douglas, who in 1987 published Gil’s Yellow Floor, was teaching at Temple. My most significant collaboration with Gil was his 1987 publication of my book-length essay-in-verse, Artifice of Absorption, as the first issue of volume 4. This publication marked Gil’s turn from magazine to book publishing. It was Gil’s and my first experiment with producing a book directly from a computer file. There were so many errors that crept in that the process itself seemed to be insisting on a level of textual impermeability well beyond the desires of author and publisher but suitable to the work at hand. Charles Alexander was first published in the second-to-last issue of Paper Air in 1989 (4:3). Maggie O’Sullivan in the last (4:4).

Gil’s Singing Horse Press published Harryette Mullens’s S*PeRM**K*T and Muse and Drudge. Also Rosmarie Waldrop, Rob Fitterman, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Ammiel Alcalay, Asa Benveniste, Kevin Killian, Lin Dinh, Norman Fischer, Chris and Jenn McCreary, Julia Blumenreich, and Eli. Charles Alexander’s Near or Random Acts was Gil’s last Singing Horse Press release and at the same time the first book in the new life of the press, under the very capable hands of Paul Naylor.

Gil spent his last weeks at the University of Pennsylvania hospital intensive care unit, just a couple of blocks from my office during the first year I was at Penn. About a week before he died, Bob Perelman and I went to see Gil. He was miraculously self-possessed, engaged with the conversation, ironic, barbed. If my eyes had been closed I imagine I could have been across the street, chatting in my Fisher-Bennett Hall office. There was little in his voice that reflected the grim intensity of the surroundings or his physical circumstances. Gil spoke of his forthcoming book, The Amputated Toe, from Kyle Schlesinger’s Cuneiform Press, as his “last” book and wondered if Kyle knew it was his last. Bob and I offered an alternative meaning to “last”: “you mean your most recent book.” Then Gil told us the story of how anxious Asa Benveniste had been for Gil to bring out his Singing Horse book, Învisible Ink, though Asa never explained to Gil that he was dying, that this was to be his last book (which, indeed, Asa did see before he died).

Just this fall, Susan, Maggie O’Sullivan, and I went to see Asa’s grave in Heptonstall in Yorkshire, right next to the grave of another American-born poet, Sylvia Plath. We loved Asa’s epitaph, “Foolish enough to have been a poet.”

In the ICU, Gil spoke of how extraordinary his prolonged life had been, the gift of living without his own kidneys for a quarter of a century. He said he was one of the longest surviving members of that class of early kidney transplant patients, and almost all we know of Gil and his work as a poet, editor, organizer, has been in the period of grace provided by his renal subversions.

But no number of anecdotes will bring Gil back from the dead: Gil, father of Willa, just the age of my son Felix, who was eleven when her father died; Gil, life and afterlife companion to Julia Blumenreich; Gil, friend to so many of us.

Listen to Gil Ott on PennSound – I made two of those recordings, both at Ear Inn in 1987 and ’89.

In a 1989 note he wrote for Patterns/Contexts/Time, a collection of responses to current conditions of and for poetry, which I edited with Phillip Foss, Gil wrote:

Humanity is suffering an epochal sickness; we fool ourselves to think the fever has diminished since Buchenwald, Sharpeville, or McCarthy. For that matter, it is only with greater difficulty each day that we adhere to the rules of the plantation, extending and repeating rather than exploding tradition on every front. Instead, too many of us continue hedging our bets within accepted modes of scholarship and literary activity, waiting for our checks and our sterile audiences.

Dead poets have one trick left: they live in our ears, in our minds, in our personal hereafter.

Foolish enough to have been born a poet.

We

take the form

of our uncertainty

Trace Peterson made this video of my talk, starting just a few moments after I began: