Some of These Daze

Mimi Gross / Charles Bernstein 9/11 collaboration

published by Granary Books

2006, 64 pages

10 1/4" x 11"

edition of 65

copies avaialble for sale from Granary

Powerpoint file of the entire Granary book

Or download a pdf file of the Granary book

Mimi Gross on Some of These Daze:

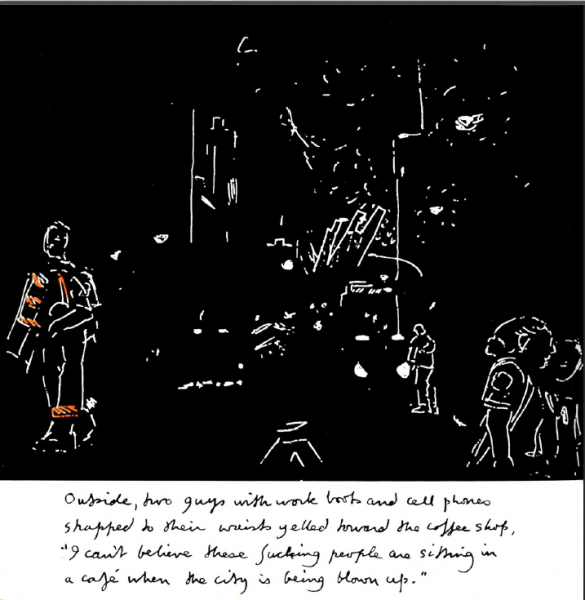

On the day and night of 9/ 11, I went out to draw the people, cars, and everything going on in the dark streets. On Church Street I found a TV crew with lights and hung around there where I could see my sketchbook.

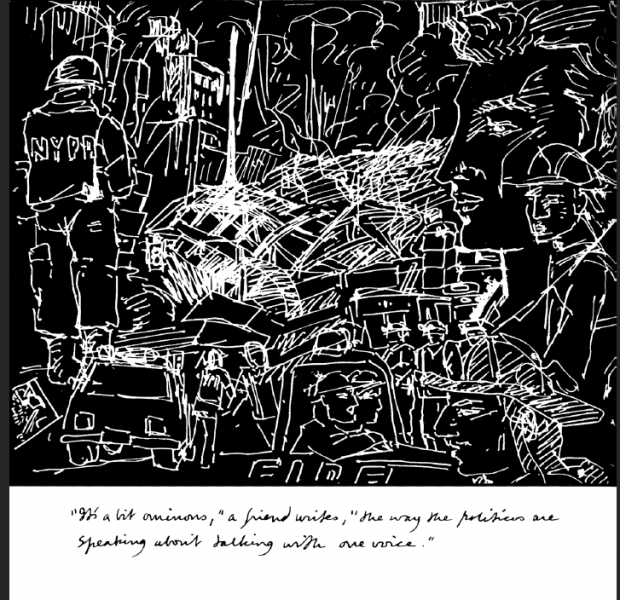

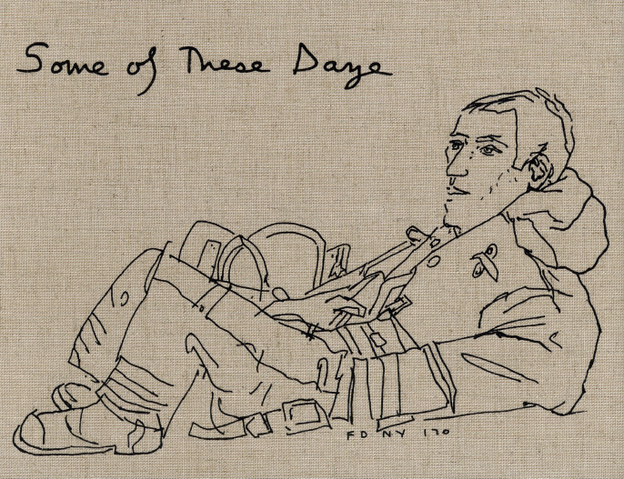

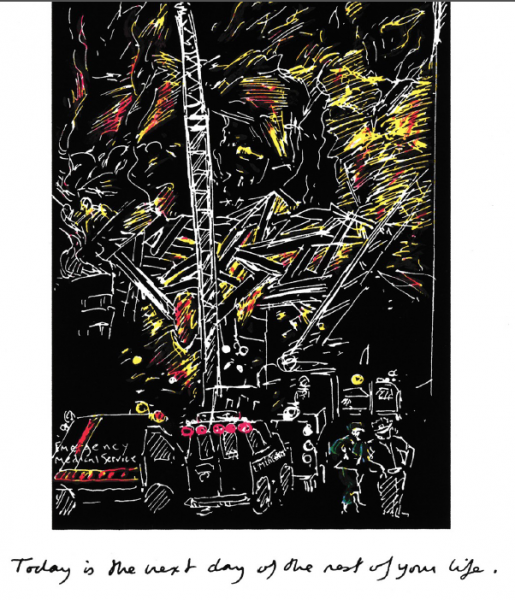

The next day and night further downtown in the middle of the chaos, the police were pushing me to "move on" while I was drawing. A TV crew from MSNBC recognized me from the night before. They sent the police away and ushered me behind the barricade reserved for the world journalist pool. While reporting, the journalists stood on a milk box, so that the burning Building #7 was clearly in the rear of the TV image. Journalists from each network took turns every hour or so to update news to the rest of the world. With all the cameras around, the novelty of having a documenting artist drawing with pen and pad was encouraged by the TV crews. I was interested in the unheralded heroes: the fire fighters, the medics, the ministers, the dogs. There was endless traffic of every imaginable vehicle—fire engine, ambulance, freezer truck, police car, garbage truck—all entering and exiting at the one gate.

By the middle of October I stopped drawing in the streets. The city contracts began. The debris was getting trucked out, the structural remains were beginning to be dismantled, and thousands of tourists wandered around looking for Ground Zero.

At first, I made black-and-white copies of the drawings. I inverted them so that the lines were white and the background black, so the contrast was more dramatic. I faxed the images to friends to share my experiences.

In late September, I heard Charles Bernstein read at the Zinc Bar. He read about his own impressions and experiences during and after 9/ 11. I was impressed that he wrote personally and universally. Everyone in the audience felt our own vulnerabilities in the way he described them. Charles and I talked about the possibility of combining our impressions. The drawings and different versions of the text were scanned, and made into a CD for the Robin Hood Fund (which was giving contributions to families of the victims at the time). Later, Steve Clay showed an interest in making a book.

Much later, we had a great collaborative moment with all of the inverted prints spread out on the floor. Charles and I edited them together, putting them into a chronology. After selecting one of Charles’s texts, he matched his lines with the drawings. I put the drawings up in my studio with the words typed out under them, and Steve and Charles came to see the layout of the book. We discussed size, format, types of printing process (linocut, lithography, etching, and finally, silkscreen), and format for the writing. I started to color some of the inverted drawings, which was challenging. By limiting the colors I wanted to evoke the chaotic intensity of night time. Kathy Keuhn coordinated the production of the book. We worked well together and her contributions are equally collaborative.

The amazing warmth of New Yorkers in the weeks after 9/ 11 will be remembered by all of us who experienced it. The neighborhood, blocked off at Canal Street, was mainly in a blackout, the air indescribably acrid, bottled water piled on side walks. During that time we lived with suspense, war, history, and a singular sense of caution.

Charles Bernstein on Some of These Daze

“I really believe one must learn to draw as easily as if it were writing.” – van Gogh

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was on my way to LaGuardia airport to catch a flight to Buffalo. Mimi Gross was at home on White Street, in lower Manhattan. Throughout the next days, Gross wandered through the area around the World Trade Center, drawing both incessantly and incisively. I returned home to the Upper West Side and wrote a series of reflections on the unfolding events. In Some of These Daze, we have merged Gross’s drawing and my writing, our respective inscriptions, as if they were two sides of the same page. The result is a double parallax view of 9/11: verbal / visual; on the spot / on the periphery.

Both Gross’s drawings and my writings rely on a serial aesthetic: one perception immediately follows the next, without an attempt to create an overall hierarchy or controlling narrative. The truth is in the array of particular details. Immediacy is valued more than commentary; local observation over symbolic resolution. While we created the writing and drawing separately, we worked together to find text to go with image and then to order these units. Similar to film editing, there was a high ratio of images and text “shot” to what we used. One memorable evening in Gross’s house in Provincetown we lay the pictures out of the floor and mapped a path, one to next to next. Just as with finding the words to go with the images, there was a shared sense of judgment that required little discussion.

Like my writing, Gross’s drawing consists of black lines on white paper. Because drawing and writing share an origin and function as notation, I wanted the artist’s hand to be present in creating both the letters and figures, as if to better meld the two, often sovereign, realms. The relation of words to pictures, especially in artist’s books, is an active concern; not to have the words provide captions for the picture, or for the pictures to illustrate the words, but for the words to provide n-dimensionality to the visual experience, coloring the mood or ambiance more than conveying information. In this work, the words are a kind of drawing and the drawing is a form of writing. This is not only because of the words embedded into some of the picture, or the way that cross-hatching often evokes letters, but also because the combined effect of the words and pictures enlist the lines into a pictogrammatic space

Our integrated approach to the verbal-visual field is further enhanced by the movement from 2- to 2½- to 3-D in Gross’s drawings. Gross’s technique is to create both concave and convex contours in her drawings, with the oscillation between them being the “2½”-D factor. Early on, we decided to make significant use of black-white reversals. The white lines on black ground suggest an enduring night but also push the drawings to a more insistent three-dimensionality: the black background pops the white lines out, transforming the image into something close to haunted maquettes for stage sets. The viewer is ushered into the underworld. The white lines are cracks through which light breaks out of the dark.

I can’t help but wonder: What is the equivalent, in writing, of white lines on a black ground?

The final, crucial, visual element on which I want to touch is the active use of color. Color moves the book out of the realm of documentary, or the real, and into the realm of the Imaginary. Gross’s precise color highlighting transforms the visual space in a way analogous to how the words transform the works to n-dimensionality. It’s as if we have created a 3-D movie where the viewer puts on imaginary spectacles with separate text and picture lenses; these spectacles superimpose the double parallax view onto a single virtual (or emerging) field.

There’s no gaze like the present.