"furnishings in the house of the voice": an interview with Hank Lazer

by Lisa Russ Spaar

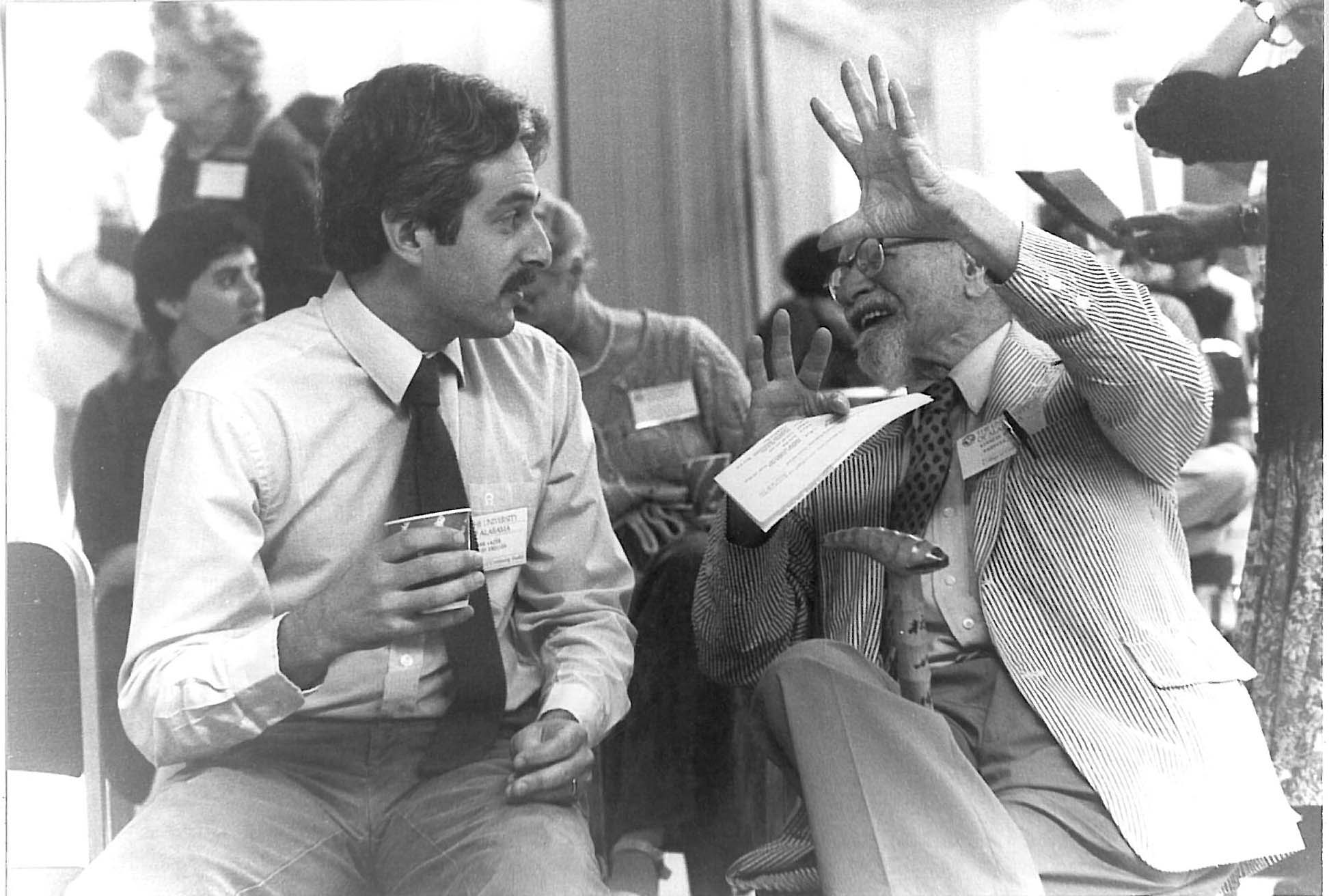

photo by Charles Bernstein

In the fall of 1975, while a second-year undergraduate at the University of Virginia, I attempted to enroll in an introduction to poetry writing course being taught by a doctoral student named Hank Lazer. I went to the first class meeting and found some 40-plus eager students hoping to gain a spot in the 15-person workshop. At the front of the room sat our long-haired, handsome, almost beatific instructor, distributing questionnaires meant to assess our interest in the class. What kind of music stirred us? Did we engage with visual art? How? By whom? Who was our favorite philosopher? Why? What foods did we most enjoy?

A 19-year-old from New Jersey, I had never met anyone quite like Hank, fresh from California’s Stanford University, in his Earth Shoes, sipping apple juice. Nor had anyone had ever asked me about myself and my artistic and extra-literary inclinations in quite this way. I’m still not sure how I gained a spot in Hank’s class, though I thank whatever compelled me to erase “Bachmann Turner Overdrive” and replace BTO with Rachmaninoff, whose compositions, brought to life by Arthur Rubenstein, scratched out of the family stereo cabinet throughout my childhood in a way I suddenly felt invited to appreciate.

It had been my original hope, in applying to Hank’s class, to enroll in a course that would provide a relatively “easy” work load in what I was anticipating would be a busy semester. I would turn in the few poems I’d scribbled in high school and sail through. On the second day of class, however, when the lucky fifteen convened, Hank handed us mimeographed sheafs of poems and translations by Rexroth, Levertov, Kinnell, Kunitz, Rukeyser, Roethke. This was the first time I’d read any poetry post William Carlos Williams, except for the occasional Joni Mitchell or Bob Dylan lyric that intrepid student or substitute teachers would sneak into our central New Jersey high school English curriculum. Here, suddenly, were poets speaking in voices I recognized as contemporary, alive – vital, political, desiring. I knew then that 1) I would never dare turn in anything I’d written in high school for Hank Lazer, and that 2) I was in for a wild and challenging ride, one that might quite possibly change my life.

Since my time in Hank Lazer’s workshop, I have followed his career with great admiration and interest. After earning his Ph.D. in English from the University of Virginia, Lazer embarked on an academic career at the University of Alabama, where he has taught since 1977. A professor of English, Lazer served as Assistant Dean for Humanities and Fine Arts from 1991 to 1997, and as Assistant Vice President for Undergraduate Programs and Services from 1997 to 2006. He is presently the Associate Provost for Academic Affairs and director of the Creative Campus initiative. He has published 16 books of poetry, including Portions (2009), The New Spirit (2005), and Days (2002), and several books of essays, including Lyric & Spirit (2008). An avid interdisciplinary artist, he has collaborated with jazz musicians, painters, dancers, and videographers. With Charles Bernstein, he edits the Modern and Contemporary Poetics Series for the University of Alabama Press.

Always interested in giving himself creative challenges, Lazer set out on October 8, 2006, to fill as many notebooks as could be completed during the time it took him to read Heidegger’s Being & Time, with Heidegger’s two themes also at the heart of Lazer’s project. The first phase of the Notebook project took two and a half years and led him through ten notebooks of varying sizes and materiality. Working by hand in what might be called a “concrete” mode, Lazer says that he allowed the dimensions of each new “space” to suggest “a relationship of black and white on the page – and then [I would] write words to actualize the shape as envisioned. The shape of the notebook itself is always a crucial factor in the composition. I never work from drafts. I see the page and its shaped writing, and I begin writing; I think of these compositions as improvisations. I immediately write the words to the specifications of the envisioned page.”

After completing Heidegger’s book, Lazer didn’t feel ready to abandon his own “shape-writing” project, and so he embarked on phase two, linked to a reading of works by Heidegger’s student Emmanuel Levinas. Lazer expects to complete the entire Notebook project this year or next. More about the Notebooks project and Lazer’s process in them, and in general, can be found here:

Arty Semite (The Forward)

9th St. Labooratories

Rob McLennan's blog

It is therefore a pleasure, nearly 36 years later, to catch up with Hank and to ask him a few questions about, among other things, his path as a writer since our time together at the University of Virginia. In particular, these questions concern his current poetic project, The Notebooks (of Being & Time). The interview is below, followed by two heretofore unpublished poems from the Notebook series, with brief commentary.

––Lisa Russ Spaar

The Interview

The Interview

LRS: As I type to you, at my left elbow is my treasured copy of your first book, Mouth to Mouth, a limited edition letterpress chapbook printed and published by the Alderman Press in 1977. My copy is number 47 out of a run of 125, signed by you in a hand I recall from your comments on my student poems and with which I have become even more familiar, reading through facsimiles of the autograph pages of your Notebooks project. The poems from Mouth to Mouth look like many poems being written in the 1970s – most are narrative, strophic, with fairly short and often enjambed lines. Yet in this early work are signs, to me, of the poet who would emerge in 1992 in INTER(IR)RUPTIONS (Generator Press) and especially in the comprehensive Doublespace: Poems 1971 - 1989 (Segue): experimental, innovative, intertextual, concrete, bearing, as Charles Wright would put it, some of the “cockleburs” of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry. In Mouth to Mouth, for instance, a butcher’s hands are signed with blood; an ode to Denise Levertov riffs on the vowels O and U; in “Point Sur” we have numerals and signage: “LA 300 à.” You have written elsewhere about what might appear to be your “conflicting modes of writing” and quite eloquently, too, about your heuristic process, “a deliberately changing approach to how to write, what is a poem, etc.” As you’ve said in other contexts, continually refreshing your practice through external obstructions and constraints is a means of avoiding becoming self-parodical; it also keeps vital and even foregrounds process and praxis over establishing a sustained singular voice. But what I’d love to hear you address here is the very specific things that happened to you as a poet between 1977 and 1992 (what did you read, encounter, realize, confront – aesthetically, professionally, spiritually) that stirred this striking shift from those early more traditionally recognizable lyric poems into your forays into a more experimental poetics, your “lyric laboratory”?

HL: Yes, that is the odd chronology of my publishing career. After the chapbook Mouth to Mouth in 1977, it took another fifteen years for the next publication, and thus when my first big book of poems, Doublespace, came out in 1992, I was already 42 years old. It’s often hard for younger writers (and ourselves as younger writers) to understand, but poetry ain’t a sprint…

As for the specific things that happened between 1977 and 1992, there were several. No single Hollywood moment of realization. From the very beginning of my endeavors as a poet, approximately 1970, I’ve written both poetry and essays, and I’ve always read both poetry and essays (or philosophy – not as a student or a professional, but as an amateur – i.e., for the love of it), and I’ve always felt the two modes of writing as part of a single ongoing activity of thinking and conversing. So, I never ingested the academic separation of creative and critical writing (which was most acute in the 1970s and 1980s as MFA programs were rapidly expanding and gaining in numbers and resources). When I taught you at UVa in the mid-1970s, I was a Ph.D. student who wrote poetry. I became a Ph.D. student rather than a creative writing student because I felt like I needed to read lots more. (I began college as a math major, and then drifted through pre-med before ending up in English.) When I came to Alabama in 1977, I was stone-walled out of any involvement with the creative writing program, and for a couple of somewhat lonely and confusing years, in terms of any kind of public existence as a poet, I was forced back onto my own resources. (In fact, I was not able to give a reading on my own campus for a period of 15 years.) I found, though, that through correspondence (the old snail mail) and sporadic travels, I was able to develop an important network of poet-friends. One key moment in that process: I attended the symposium that Richard Jones organized at UVa in the late 1970s, and I stayed at Chuck Vandersee’s apartment. The other guest at Chuck’s place was the poet David Ignatow. For a year or two, I had been writing poetry that deliberately broke with what you’ve called the fairly typical writing of the 1970s – plainspoken, narrative, epiphanic. Why did I do that or feel that it was necessary? Because that reigning self-expressive singular voice mode of writing ruled too much out. I felt that too many of the questions that interested me, too many areas of thought (and emotion) were not possible in such a mode of writing. And too many ways of writing were ruled out. So, I began an overtly philosophical mode of writing, exploring the abstractions that had been at the top of the DON’T list for the emerging workshop ideology. I showed these poems to David, and, like a good doctor, he gave me a prescription: read (George) Oppen. I began to do so immediately, and to this day Oppen matters to me as much as any poet. (And David Ignatow and I remained friends for the rest of his life.)

Perhaps it is my lack of affiliation with creative writing that made it plausible for me to explore some radically different ways of writing poetry. While at first the lack of a public platform and the lack of an institutional identity as a poet proved difficult, ultimately it freed me to take different kinds of chances and to develop my writing (and its publication) at a pace totally unrelated to job, salary, and professional advancement considerations.

In 1984, I organized the infamous "What Is a Poet?" symposium at Alabama. [Photo: Lazer with Kenneth Burke at the symposium.] I invited Marjorie Perloff, and she introduced me to Charles Bernstein, and we became and remain good friends. While I was late to the Language movement and not a part of its early publication network, and have always had a mixed sense of kinship and disagreement, I shared their simultaneous nourishment from theory/philosophy and poetry. In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, I learned a great deal about what might be possible in poetry from a broad range of writers whose work I read and who became friends: David Antin, Jerome Rothenberg, Lyn Hejinian, Ron Silliman, Nathaniel Mackey, Charles Alexander, Harryette Mullen, Susan Howe, Robert Creeley, Susan Schultz, John Taggart … My own readings in Heidegger – toward the end of my time at UVa I read and was deeply affected by Poetry, Language, Thought – and Derrida were also crucial to what I considered to be possible in poetry.

In 1984, I organized the infamous "What Is a Poet?" symposium at Alabama. [Photo: Lazer with Kenneth Burke at the symposium.] I invited Marjorie Perloff, and she introduced me to Charles Bernstein, and we became and remain good friends. While I was late to the Language movement and not a part of its early publication network, and have always had a mixed sense of kinship and disagreement, I shared their simultaneous nourishment from theory/philosophy and poetry. In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, I learned a great deal about what might be possible in poetry from a broad range of writers whose work I read and who became friends: David Antin, Jerome Rothenberg, Lyn Hejinian, Ron Silliman, Nathaniel Mackey, Charles Alexander, Harryette Mullen, Susan Howe, Robert Creeley, Susan Schultz, John Taggart … My own readings in Heidegger – toward the end of my time at UVa I read and was deeply affected by Poetry, Language, Thought – and Derrida were also crucial to what I considered to be possible in poetry.

The two books that you cite, INTER(IR)RUPTIONS and Doublespace (the latter with some lengthy back cover comments by David Ignatow and Susan Howe), were both published in 1992, and I’ve been publishing books fairly steadily ever since with 14 books of poetry since 1992 as well as three books of essays. What the two 1992 books have in common is an exploration of possibilities for collage – a principle that I learned about from David Antin and Marjorie Perloff, among others.

Your reference to Mouth to Mouth piqued my interest, and I looked at it again. In addition to the poems you point out, I’d note that the new directions in my writing are perhaps most foretold in the poem that begins on page 5: “in attention to sound/ is the wife to meaning/ made. In prayer for/ the coming forth or/ that which is not yet known/ though to be hoped for/ in time”.

LRS: I think I’m correct in thinking that the two pieces that we’re featuring—N18P60 (“we will speak to each other reporting”) and N18P64 (“only to the high tower climb mistaken story of the young”)—come from the second phase of The Notebooks (of Being & Time) series, during which you were reading Heidegger’s student Emmanuel Levinas. Can you date the poems for us? What text exactly were you reading by Levinas at the time? These two poems seem themselves to have come close together “in time” – are they from the same notebook? Can you describe the notebook for us – dimensions, cover, paper weight and texture – and your script – is it in ink? Black? Special kind of pen? I’d love to hear how the material techne at hand, so to speak, affected and generated the vocalization/song of these poems, and vice versa.

HL: N18P60 was written on 12/11/10; N18P64 on 12/18/10. I was reading Lévinas’ Otherwise than Being. Yes, they are from the same notebook – N18 indicates notebook #18; P60 is page 60; a simple way of cataloging the work. Notebook 18 is 70 pages in length; the page dimension is 5 ¼” X 8”; it’s an Ethiopian binding with wavy blue hardbound covers; a nice quality, not overly porous paper, without much texture to the pages. (In the course of what I project to be a 20 notebook project, there is huge variation in all ways – page size, page texture, length of notebook.) The script is black ink (though in the course of N18 there is some blue ink, and two different shades of black ink). Most of N18, including these two pages, are written with a fine point Sharpie pen. (The other black ink is my basic writing pen, a fine point Papermate Comfortmate, as is the blue ink.) I had been using the Papermate fine points, but when I worked with book artists Steve Miller and Anna Embry on a collaborative project – a series of 9 bilingual notebook pages called Indivisible - with some Cuban visual artists, they recommended the Sharpie to me for its consistency of inking (and they were right, though for very small writing, I still prefer and use the fine point Papermate pen). The page size and paper texture are absolutely crucial to what I write. I think of each page as a one-time improvisation, and the page itself and notebook design are partners in what is possible.

HL: N18P60 was written on 12/11/10; N18P64 on 12/18/10. I was reading Lévinas’ Otherwise than Being. Yes, they are from the same notebook – N18 indicates notebook #18; P60 is page 60; a simple way of cataloging the work. Notebook 18 is 70 pages in length; the page dimension is 5 ¼” X 8”; it’s an Ethiopian binding with wavy blue hardbound covers; a nice quality, not overly porous paper, without much texture to the pages. (In the course of what I project to be a 20 notebook project, there is huge variation in all ways – page size, page texture, length of notebook.) The script is black ink (though in the course of N18 there is some blue ink, and two different shades of black ink). Most of N18, including these two pages, are written with a fine point Sharpie pen. (The other black ink is my basic writing pen, a fine point Papermate Comfortmate, as is the blue ink.) I had been using the Papermate fine points, but when I worked with book artists Steve Miller and Anna Embry on a collaborative project – a series of 9 bilingual notebook pages called Indivisible - with some Cuban visual artists, they recommended the Sharpie to me for its consistency of inking (and they were right, though for very small writing, I still prefer and use the fine point Papermate pen). The page size and paper texture are absolutely crucial to what I write. I think of each page as a one-time improvisation, and the page itself and notebook design are partners in what is possible.

LRS: Both poems strike me as coming from a similar matrix, linguistically and thematically. In particular, I’m drawn to their preoccupations with “story,” “voice,” wandering/seeking, and the simple/basic is-ness and this-ness. In an essay “Poetry & Myth,” you write, with regard to Robert Duncan, “I recognize a general uneasiness of many contemporary innovative poets (particularly Language poets) with myth. Within current experimental poetries, Duncan, somewhat like Charles Olson, is a difficult figure. Often, contemporary innovative poetries exhibit a textualized coolness, an ironized distance instead of the intense emotional directness of Duncan’s poetry . . . . [T]he reception and continuation of Duncan’s writing is often accompanied by an evasion of his active emphasis on spirit, myth, emotional intensity, his affirmation of the heart and of love, and his generally romantic version of the artist/poet.” I’d like to suggest that something similar is also true of your own work, Hank. Your poems frankly address somatic ardor and appetite as well as a keen interest in “the quest” or the Way. Unless I’m mistaken, I sense a spiritual joy in your work, and in the Notebook project in particular. Can you talk about these poems as kind of spiritual “play” and/or as part of a devotional if not a religious practice or sojourning?

HL: You are absolutely right. (I describe myself as a Jewish Buddhist agnostic.) Increasingly, my writing – again, both poetry and essays – has been devoted to an exploration of new modes of spiritual experience and expression, or, as I like to think of it, a phenomenology of spiritual experience. Thus, books like The New Spirit (poetry, 2005), Lyric and Spirit (essays, 2008), and Portions (poems, 2009, playing with the tradition of Torah-portions); in recent essays, I’ve been exploring a radical Jewish poetics. The Notebooks indeed do feel like a devotional or religious or spiritual activity. I usually write the notebook pages in the early morning, often on weekends (as my administrative work has been full-time for the past twenty years), so the thinking and the reading that go into them will often take place after my morning meditation (zazen). For most of the pages, I have a kind of vision – a sense or seeing of what the shape of the writing will look like – though I have very little idea of what the words will be. Once I “see” the page, I begin writing. Many of the pages incorporate quotations from my reading (initially, in the first ten notebooks, from Heidegger’s Being & Time; in notebooks 11-20, from a series of Lévinas’ books). Thus, there is a channeling or dictation aspect to the writing (particularly since I do not write any drafts nor do I work from notes or sketches). Perhaps the notebook pages can be thought of as prayers or gestures or devotionals that seek to deepen my feel for being & time? And yes, play is part of it, including plenty of bad puns and lame jokes, as well as the somewhat childish or child-like activity of making a shape with words. I like, too, your suggestion of the page as a “sojourn,” with the root word for day, “jour,” embedded in that word. The pages are each a day’s devotion, a way of beginning a day, of entering into and blessing that span of time and one’s jour-ney in it.

HL: You are absolutely right. (I describe myself as a Jewish Buddhist agnostic.) Increasingly, my writing – again, both poetry and essays – has been devoted to an exploration of new modes of spiritual experience and expression, or, as I like to think of it, a phenomenology of spiritual experience. Thus, books like The New Spirit (poetry, 2005), Lyric and Spirit (essays, 2008), and Portions (poems, 2009, playing with the tradition of Torah-portions); in recent essays, I’ve been exploring a radical Jewish poetics. The Notebooks indeed do feel like a devotional or religious or spiritual activity. I usually write the notebook pages in the early morning, often on weekends (as my administrative work has been full-time for the past twenty years), so the thinking and the reading that go into them will often take place after my morning meditation (zazen). For most of the pages, I have a kind of vision – a sense or seeing of what the shape of the writing will look like – though I have very little idea of what the words will be. Once I “see” the page, I begin writing. Many of the pages incorporate quotations from my reading (initially, in the first ten notebooks, from Heidegger’s Being & Time; in notebooks 11-20, from a series of Lévinas’ books). Thus, there is a channeling or dictation aspect to the writing (particularly since I do not write any drafts nor do I work from notes or sketches). Perhaps the notebook pages can be thought of as prayers or gestures or devotionals that seek to deepen my feel for being & time? And yes, play is part of it, including plenty of bad puns and lame jokes, as well as the somewhat childish or child-like activity of making a shape with words. I like, too, your suggestion of the page as a “sojourn,” with the root word for day, “jour,” embedded in that word. The pages are each a day’s devotion, a way of beginning a day, of entering into and blessing that span of time and one’s jour-ney in it.

The spiritual practice of the writing is beautifully described by Robin Blaser: “To be in the language is a profound pleasure of writing and reading – the old word for this is enchantment – and it is not the same as an appropriation of the language to the self or a formality.” Blaser points toward a way of proceeding that allows one “constantly to be vulnerable to the condition of writing,” so that the moment of writing becomes “the looking into something as it composes in the poem.” Blaser reminds us that “language is not our own” and that “our poetic context involves relation to an unknown, not a knowledge or method of it.” Perhaps the way I go about writing the notebook pages deepens this engagement with language as a fundamental other or unknown, something that I partner with in the making or manifesting of the pages. What I’m describing as the experience of writing the notebooks is my own sense of what you, Lisa, in your question refer to as spiritual play.

LRS: Clearly poem-making is more than gaming, though I do admire the ways in which assigning yourself certain parameters of quantity and duration free you to work freely and serially in perpetually fresh ways (I wonder if you’ve seen Lars Von Trier’s wonderful film about how art loves limits: The Five Obstructions?). Would you name three poets and/or poems to which you turn and return for sustenance – emotional, spiritual, artistic – poems that help you to live?

HL: George Oppen (particularly “Of Being Numerous,” but truly, all of his writing); Lao-tzu’s dao de jing (sometimes transliterared at Tao te ching; Thomas Meyer’s translation, published by Flood Editions, preferred); Thoreau (Walden, but also the Journal). If you gave me a fourth poet for the list, it would probably be Rilke. I did see Von Trier’s film, but I’m really not much of a film person… Though I do work in invented forms, particularly with the Notebooks (which have variety and difference from page to page built into the methodology) I do not really experience the design of the work as an assignment or an obstruction. Much more of an invitation or an opening.

LRS: Finally, if there’s time and you’re so inclined, ask a question you’d like to answer for this interview, and then do so. With my utter thanks!

HL: What are you learning in the course of writing the Notebooks? What does this particular approach – shape-writing, handwritten pages, with a radical change of shape from page to page – make possible?

I’m learning about how intensely focusing an activity improvisation is – composition (one draft, no notes, no revision) in real time. I’m learning – rather unexpectedly – about an intriguing intersection that occurs in shape-writing, a meeting of a kind of naiveté and philosophical thinking – outsider artist amateurism (amor is the root word for amateur, a term which I do not use in a derogatory sense) colliding and colluding with high philosophy. The writing in shapes has also freed me to be more direct or flat with certain philosophical observations. I am also learning that the 20 notebooks (which involve well over 1,000 pages) will become and are becoming a source for multiple possible books. I am hoping to publish Notebook 18 in its entirety. I have already had a fine press limited edition (53 copies) of Indivisible printed – 9 pages from the Notebooks, in a bilingual handwritten edition, plus a landscape (double-page foldout) written especially for the project. I learned from Indivisible that, oddly, it is much more difficult to “copy” a previously written page than to write it the first time. The translated pages, in Spanish, had to assume a slightly different shape than the “original” page. I am also beginning to create another book-extraction called Extracting the Jewish Book. I also entertain the thought of working with several book artists to create a series of twenty chapbooks, each of which would interpret and extract from a specific notebook. I am also learning that this allegedly primitive technology – handwriting – has some capacities, subtleties, and complexities that cannot really be achieved in a digital environment. For example, one of the notebooks is an accordion notebook, and it is written on both sides to create a kind of moebius strip or infinite loop. Similarly, as I read from or perform the notebook pages, the possibilities for audience participation and multi-voice creations are surprising and engaging. I have performed several notebook pages with jazz musicians, and I continue to learn from improvisatory or free jazz, particularly from the work of colleague and friend Andrew Dewar, a soprano sax player who studied with Steve Lacy and who performs with Anthony Braxton’s band. I have some schemes in mind for ways of presenting the notebook pages in readings (including projection of the pages themselves, and voice layering). In ways that I had not anticipated, the poem/page becomes a launching off point for other modes of its existence. We’ll see what’s possible.

Lisa Russ Spaar, poetry editor for Arts & Academe, is a professor of English at the University of Virginia.

See also: http://chronicle.com/blogs/arts/an-interview-with-hank-lazer/29495, which includes a condensed version of this interview, as well as a second part which includes two poems/pages from the Notebooks, accompanied by a transcription of the pages, along with a discussion of the poems/pages by Lisa Russ Spaar.