'Gertrude Stein's Translations of Speeches' by Philippe Petain

Carefully stowed and catalogued among the 173 boxes of the Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library are three unremarkable folders containing translations of Philippe Pétain’s Paroles aux Français.[1] Alongside Stein’s introduction,[2] the manuscript notebooks and few typed pages they contain are the corpus delicti of her collaboration with the Vichy regime. Despite their centrality to the controversy over Stein’s war years, however, the contents of these folders (thanks probably, in part, to Stein’s more than usually formidable handwriting) have not been extensively studied or understood. It is the purpose of this piece to clarify what they contain and to offer a suggestion as to why Stein translated Pétain’s speeches the way that she did.

Perhaps the most detailed description available of Stein’s Pétain translations is given by Barbara Will in her recent book, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Regime. If I quote Will at length, it is because her words serve as the best introduction:

At the end of 1941, Stein undertook a project to translate the speeches by Philippe Pétain that had been collected in a book edited and introduced by Gabriel-Louis Jaray, a friend of Bernard Faÿ. It was no small endeavor. For the next year and a half, Stein translated some thirty-two of Pétain’s speeches into English, including those that announced Vichy policy barring Jews and other “foreign elements” from positions of power in the public sphere and those that called for a “hopeful” reconciliation with Nazi forces. The last of Pétain’s speeches that Stein translated was from August 1941, but Stein did not cease working on the project until January 1943 — several months after the Germans had occupied the whole of France in November 1942 and long after the United States had entered the war against the fascist forces that Stein was promoting to her fellow Americans. […] The first speech translated is Pétain’s address of 1936, delivered at the inauguration of a monument to the veterans of Capoulet-Junac; the last, Pétain’s 1940 Christmas address. Stein followed the erratic chronology of the original text, Paroles aux français, messages et écrits 1934–1941, translating approximately the first half of the fifty speeches published. Still, she leaves some speeches untranslated, and it is interesting to speculate as to why.[3]

Here, as elsewhere in her absorbing account, Will’s historical research regarding the circumstances of Stein’s project is thorough. Apparently translating until January 1943 when “her friend Paul Genin and the sous-prefet of Belley, Maurice Sivan, urged her to abandon the project,”[4] Stein continued her work for three months after the United States had severed diplomatic relations with the Vichy government. There are, however, two potentially misleading details in Will’s description of the translations themselves which are worth clarifying. Firstly, by my count, Stein translated only twenty-seven full speeches (one of which is separated into five sections).[5] Among these twenty-seven there are abortive attempts at two others, making a total of twenty-nine, not thirty-two. At the beginning of folder 1141 are also typescript copies of part of the second speech and all of four others (listed below as 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). Since the original French version of these speeches is easily accessible, both in the volume that Stein used[6] and in more recent critical editions,[7] I include here a list of their dates, so that the curious reader may consult their contents:

|

Folder |

Speech |

Date |

Number of Speech in Paroles aux Français |

Title of Speech in Paroles aux Français and Notes |

|

1140 |

1 |

1936 |

II |

Le paysan français |

|

1140 |

2 |

1938 |

III |

Pour l’union des Français |

|

1140–1141 |

3 |

November 1938 |

IV |

L’abandon de la vie spirituelle et de l’esprit national |

|

1141 |

4 |

17th June 1940

|

VI |

Appel du 17 juin 1940 |

|

1141 |

5 |

22nd June 1940 |

VII |

Appel du 20 juin (Misdated by Stein as 22nd June) |

|

1141 |

6 |

20th June 1940 |

VIII |

Appel du 23 juin (Misdated by Stein as 23rd June.) |

|

1141 |

7 |

25th June 1940 |

IX |

Appel du 25 juin |

|

1141 |

8 |

11th July 1940 |

X |

Appel du 11 juillet 1940 |

|

1141 |

9 |

13th August 1940 |

XI |

Appel du 13 août |

|

1141 |

10 |

9th October 1940 |

XIII |

Appel du 9 octobre |

|

1141 |

11 |

11th October 1940 |

XIV |

Message du 11 octobre |

|

1141 |

12 |

30th October 1940 |

XV |

Message du 30 octobre sur l’Entrevue de Montoire |

|

1141 |

13 |

18th November 1940 |

XIX |

Déclaration du 18 novembre aux représentants de la Presse à Lyon |

|

1141 |

14 |

14th December 1940 |

XX |

Message du 14 décembre sur le renvoi de M. Pierre Laval |

|

1141 |

15 |

1st January 1941 |

XXI |

Allocution du 1er janvier 1941 au Corps diplomatique (Stein only translates the first five lines of this speech, before crossing it out.) |

|

1141 |

16 |

19th March 1941 |

XXII |

Message de Grenoble |

|

1141-1142 |

17 |

7th April 1941 |

XXIII |

Message du 7 Avril |

|

1142 |

18 |

11th May 1941 |

XXIV |

Message du 11 Mai pour la fête de Jeanne d’Arc |

|

1142 |

19 |

15th May 1941 |

XXV |

Message du 15 Mai |

|

1142 |

20 |

8th June 1941 |

XXVI |

Message du 8 juin aux Français du Levant |

|

1142 |

21 |

17th June 1941 |

XXVIII |

Message du 17 juin |

|

1142 |

22 |

8th July 1941 |

XXIX |

Discours du 8 juillet sur la Constitution |

|

1142 |

23 |

12th August 1941 |

XXX |

Message du 12 août |

|

1142 |

24 |

19th August 1941 |

XXXI |

Discours du 19 août au Conseil d’État |

|

1142 |

25 |

26th August 1941 |

XXXIII |

Lettre du 26 août aux prisonniers libérés |

|

1142 |

26 |

15th September 1940 |

XXXV |

La Politique social de l’avenir (Revue des Deux Mondes) |

|

1142 |

27 |

10th November 1940 |

XXXVI |

Le Secours national |

|

1142 |

28 |

30th November 1940 |

XXXVII |

Appel en faveur des expulsés lorrains |

|

1142 |

29 |

24th December 1940 |

XXXVIII |

Message de Noël 1940 (Unfinished after two pages.) |

As the reader will observe, speeches I, V, XII, XVI–XVIII, XXVII, XXXII, and XXXIV are not translated by Stein. In addition, Stein evidently gave up on Pétain’s New Year speech of 1941 (XXI), as well as leaving the last speech unfinished. Since this speech ends with her notebook, however, Edward Burns and Ulla Dydo speculate that there may have been another notebook following on from it:

The last text translated, a routine speech for Christmas 1940, stops at the end of her manuscript notebook in midspeech, midsentence, a procedure quite unlike Stein, who was orderly and finished what she started; was there another notebook, not preserved, which might have gone beyond and revealed what happened to make her stop?[8]

Burns and Dydo do not suggest a likely answer, writing instead that “The texts and letters preserved do not give us enough facts for interpretation” (409). In what follows, I will have occasion to consider both Will’s question (why did Stein choose the speeches she did) and Burns and Dydo’s (why did she stop so suddenly?). However, taking Burns and Dydo’s warning seriously, I do not pretend to have arrived at a definitive interpretation; any conclusions suggested are speculative.

To return to the second potentially misleading moment in Barbara Will’s description of Stein’s translations. Will writes: “Stein translated some thirty-two of Pétain’s speeches into English, including those that announced Vichy policy barring Jews and other ‘foreign elements’ from positions of power in the public sphere and those that called for a “hopeful” reconciliation with Nazi forces.”[9] From this report, the reader might assume that Stein’s translations involved writing out in English the anti-Semitic and xenophobic portions of Pétain’s new policies. Certainly Stein did translate Pétain’s declarations of support for Adolf Hitler, and his injunctions to the French to collaborate with the Nazis. However, Stein did not translate any specific reference to Jews. This is not because of her selection, but for the simple reason that there are no such references in Pétain’s speeches. Although Stein did translate one speech by Pétain announcing changes in Vichy policy (Oct. 9, 1940), and although this change in policy did refer in part — but not by name — to the infamous Statut des Juifs of October 3, 1940, the speech itself does not mention the specific changes wrought on French policy. (Stein, apparently, did not translate Pétain’s announcement of modifications to this policy on June 4th 1941.) Pétain was remarkably silent on the “Jewish question” in his public pronouncements — a fact which, perhaps, can be explained by suggesting that Pétain wanted his speeches to emphasize national unity and solidity. Here are two samples of such references in Pétain’s speeches to his changed laws from October 9th, 1940, with Stein’s translations below:

Un statut nouveauprélude d’importantes réformes de structure, déterminerales rapports du capital et du travail. Il assureraà chacun la dignité et la justice.[10]

A new law a prelude to important constructive reforms will decide the relation of capital to labor. It will assure to each one justice and dignity.[11]

Dans un message que les journaux publieront demain et qui sera le plan d’action du gouvernment, je vous montrerai ce que doivent être les traits essentiels de notre nouveau regime. National en politique étrangère; hiérarchisé en politique intérieure; coordonné et contrôlé dans son économie, et, par-dessus tout social dans son esprit et dans ses institutions.[12]

In a message that the newspapers will publish and which will be the plan In the of action of the government I will make evident to you what should be the essential character of our new regime government. National in foreign politics, hierarchic in home politics affairs, coordinated and controlled in its economy, and above all social in its spirit and its institutions [?] institutions.[13]

Pétain, it seems, was careful to keep explicitly discriminatory statements out of his speeches. His euphemism for the revised polity was the “hierarchization” of France.

In 2010, a newly released draft of the 1940 Statut des Juifs revealed that Philippe Pétain was not only personally willing to propagate Nazi anti-Semitic policy in France, but went beyond Hitler by making his already appalling strictures more comprehensive.[14] However, before the discovery of this document showing the extent of Pétain’s anti-Semitism, his personal involvement in French anti-Semitic policy was debatable. Arguments to the opposite end were common: that under German pressure Pétain was forced to instigate anti-Jewish laws, but tried to temper them in France.[15] In trying to understand Stein’s actions, it is important to note that translating Pétain’s speeches would not, in itself, have brought her familiarity with the nature or extent of his involvement with the anti-Semitic policies introduced on October 3rd 1940 and June 2nd 1941. Indeed, the fact that Pétain, through the mediation of Bernard Faÿ, accepted Stein as the translator of his speeches into English may have suggested to her that he was not prejudiced against Jews. Moreover, in one of the speeches that Stein translates (30 Nov. 1940), Pétain defends the refugees from Alsace-Lorraine, of which a large portion were Jewish. Since the publication of this speech was banned by German authorities in occupied territory,[16] its translation may have seemed to Stein a long way from a pro-Nazi or anti-Semitic act. (Stein’s translation is included in the note below.)[17]

If insisting on the contemporary representation of Pétain’s person here seems like quibbling (there is, after all, no denying the fact that Stein translated speeches from the leader of a regime that contributed to the Holocaust), it is an ad hominem focus suggested by Stein’s introduction to her project. Pétain, to the Stein writing this introduction, was a mythical hero above suspicion:

Like George Washington [he] has given [his countrymen] courage in their darkest moment held them together through their times of desperation and has always told them the truth and in telling them the truth has made them realise that the truth would set them free.[18]

… one thing that was certain and that was that like Benjamin Franklin he never defecnded [defended] himself, he never explained himself, in short his character did not need any defence.[19]

everybody had feelings about the Marechal, about one thing they were all agreed and that is that he had achieved a miracle, without arms without any means of defense, he had succeeded in making the Germans more or less keep their word with him. Gradually this miracle impressed itself upon every one.[20]

I must say little by little the most critical and the most violent of us have come gradually to do what the Marechal asks all French people to do, to have faith in him and in the fact that France will live. And this is to introduce the actual words said by the Marechal when it was necessary for him to say something and it is a convincing and moving story.[21]

One might theorize that it was Stein’s own explorations of celebrity and identity in works such as Lectures in America or Everybody’s Autobiography that led her towards this stance of hero worship. Stein’s enthusiasm for Pétain in this introduction appears to have had much more to do with his personal aura than the specificities of his policy.

Looking at Stein’s translations through the optic of her cult of personality for Philippe Pétain offers a potential motivation for Stein’s choice of speeches to translate. Stein, it seems, was often more interested in those speeches in which Pétain’s rhetorical persona as the savior of France was most prominent. Thus she omits speech XVIII “Discours du 18 novembre a la Chambre de commerce de Lyon” about the organization of the state and its departments, but includes, from the same day speech XIX “Declaration du 18 novembre aux représentants de la Presse à Lyon,” which is Pétain’s response to those who have accused him of shying away journalists. The choice is not unreasonable, considering the purpose of her translations: to introduce Pétain to readers in the United States. Likewise, Stein omits speeches with distant subjects. Thus speech V, Pétain’s message on the “moral example of Canada” and speech XVI addressed to the colonies are left out, while III — “Pour l’union des Français” is included, perhaps because it foregrounds Pétain’s rhetorical role and immediate presence.

Stein’s enthusiasm for Pétain’s person has also been used, by Barbara Will, to suggest an explanation for the style of her translations. As the reader will have noticed from the samples given above, Stein’s translations are often extremely literal. Thus Will writes,

what is most striking about the text is its almost stupefyingly literal rendering of the French original. Translating word by word, Stein completely ignores questions of idiom or style: “Telle est, aujourd’hui, Français, la tâche à laquelle je vous convie” becomes “This is today french people the task to which I urge you.” An idiomatic phrase such as “Le 17 juin 1940, il y a aujourd’hui une année” becomes “On the seventeenth of June 1940 it is a year today.”[22]

One conclusion we might draw would be Stein’s own ineptitude. However, as Will points out, Stein had already composed original work in French, and had allegedly translated Flaubert’s Trois Contes, as well as Georges Hugnet’s poem cycle Enfances.[23] (Reading her literalism as incompetence, one might add, is to run the risk of sounding like “the director of the Grafton Press” in the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, who was “under the impression” that perhaps Stein’s “knowledge of english” was at fault.)[24] “Hence,” writes Will, “the striking literalism of Stein’s Pétain translations seem[s] to point to a deeper issue than linguistic ineptitude.”

Stein’s attempt to render the French original into English through a one-to-one correspondence between signs seems to be conceding authority, interpretation, and interrogation to the voice of Pétain. This compositional submissiveness suggests a subject in thrall to the aura of a great man: the savior on a white horse, as Stein describes Pétain in her introduction to his speeches. In an interview with her local paper Le Bugiste in 1942, Stein is in fact described in a curious state of ravishment: “she abandons herself to her subject, to her hero, she admires the importance of his words and the significance of the symbol.” To invoke Susan Sontag: Stein appears “fixated” or “fascinated” by Pétain, mesmerized and rendered passive by an almost masochistic desire for the figure of the authoritarian dictator.[25]

I find this conclusion highly suggestive in the ways that it makes us think about the queerness and erotic charge of much of Stein’s writing. But when one considers the kind of portrait that Will paints of Stein, one is confronted with a counterintuitive image. Stein, the author of “Patriarchal Poetry,” as a meek woman rendered passive and incapable of personal expression by her “ravishment” for the strong male dictator? Of course, more “unlikely” things have happened; beside the fact of Stein’s collaboration, such a submission to patriarchy is not inconceivable.

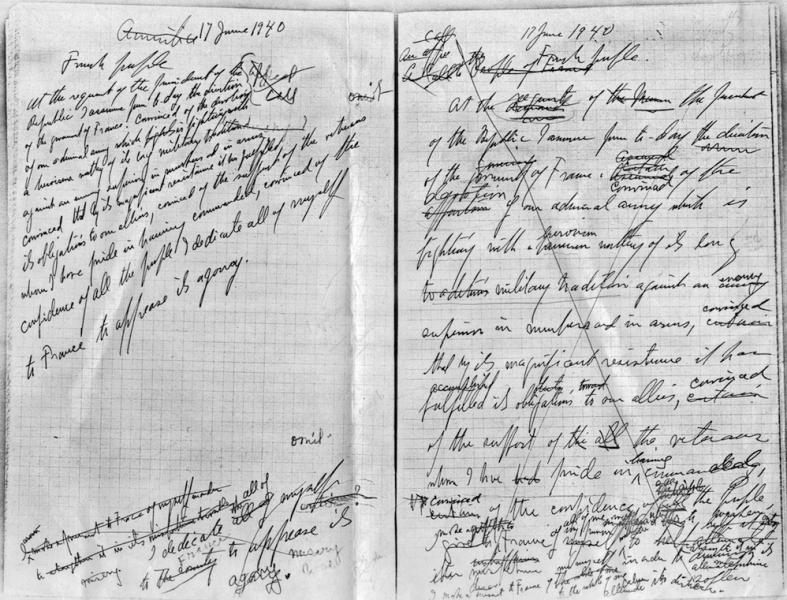

Rather than multiplying unlikelihoods, however, I suggest a more mundane option. In most cases, Stein, I think, used a literal translation because she thought that this was an appropriate way to translate prose. (In 1928, she apparently insisted that Bernard Faÿ and Georges Hugnet render The Making of Americans into French through what Ulla Dydo calls “sentence sense, as it were, word-for-word meaning.”[26] When Stein’s translation of Pétain’s speeches becomes so literal as to be sloppy, I think it is because, given the project by Bernard Faÿ, Stein rapidly lost interest in her task, and yet continued out of a dogged determination. As Burns and Dydo suggest, this would be characteristic of her, since although she often set out on projects with which she grew disillusioned, she also “finished what she started.”[27] This interpretation is supported by the fact that Stein’s translating is not ubiquitously literal. Passages where her interest was apparently more strongly engaged, particularly towards the beginning of the project, show evidence of numerous revisions, which carry the English version away from the literal French version rather than towards it. So, for example, in translating Pétain’s most memorable speech, that of his assumption of power on June 17, 1940, Stein used both sides of the notebook pages, going over multiple options for possible versions. Pétain’s line, “je fais à la France le don de ma personne pour atténuer son malheur,”[28] goes through at least ten variations. I transcribe only those that I can read:

(click here to view a high-resolution scan)

I give to France myself

I make a gift to France of my person to attenuate its misfortune

to help it out of

of all of me myself to weaken its unhappiness

misfortune

I make a present to France of the whole of me to attenuate

me myself to diminish its misfortune

soften

alleviate

calm its distress

I now make a present to France of myself in order to strengthen it in its

misfortune trouble misery. I dedicate the all of myself to the country France to

appease its misery agony.

I dedicate all of myself to France to appease its agony.[29]

One can see here a general trend away from the French constructions to less literal, and more natural-sounding English constructions. Thus with “je fais le don,” Stein settles not on “I make a gift” but on “dedicate”; and “atténuer son malheur” becomes not the stilted “attenuate its misfortunate” but the much more expressive “appease its agony.”

In contrast to this speech of June 17, 1940, Stein’s translations in folder 1142 show fewer traces of revision. The work that she probably did during the last three months of her translating — that is, during the period after the US had severed diplomatic relations with the Vichy government — appears half-hearted. A glance at the broad sweep of her handwriting in the unfinished final speech from December 1940 suggests that she was working rapidly. In the following passage, Stein seems to have always opted for the first word that came to her. The French word order is unchanged:

In many homes, there are empty places — the places of dear ones. Many will never come back, who were seated there joyously last year, on leave for ten days around the family table; that our first thought should be is for them: they have saved their honor. Others await far from you prisoners in foreign lands; perhaps they will hear this evening mass said in their camps? Perhaps they will open with love the beautiful packages that you have sent them? Never than in their xile and in their solitude They have they never been nearer to us than in their xile and in their solitude: I think this evening night of all who suffer, of those who have not in their fire-places neither wood or coal, of those who have heard, in past times in past times, spoken of in past times of Christmas eve and who do not spoken of and who do not know if they will eat to-morrow; of children who will not find toys[30]

The infelicitous phrase “they have saved honor” in French reads, “ils ont sauvé l’honneur.”[31] Likewise, the double negative “I think this night of all who suffer, of those who have not in their fire-places neither wood or coal” reproduces a French grammatical construction: “Je pense aussi, ce soir, à tous ceux qui souffrent, à ceux qui ne mettront dans leur cheminée ni bûches, ni charbon.”[32] This perfunctoriness does not seem to be the work of a translator in awe of her author; it is, however, quite possibly the work of a creative artist disheartened by a task, and one increasingly uncertain of its virtue.

Before we leap to the conclusion that Stein realized the error of her ways midway through her translations, it is worth considering that her disillusion with the project, as I sketch it here, need not have been purely due to a sense of impropriety aroused by changing historical circumstances. If one reads Pétain’s speeches in the order in which they are presented in Paroles aux Français, one cannot help feeling that the earlier portions of the work are more interesting: the narrative of Pétain’s ascent to power, his arrangement of an armistice with Nazi Germany, and his meeting with Hitler, make for more compelling reading than do his later pronouncements and struggles to maintain order. I think it is possible that Stein, regarding the political ramifications of her task as secondary, was primarily motivated by such concerns over readerly interest. This, at least, would explain why she revised the translation of Pétain’s speech explaining the meeting with Hitler at Montoire on October 30th, 1940, almost as rigorously as she did that of June 17, 1940. And, in this context, it is also plausible that when Stein reached the end of her third notebook, she did not begin another one for the simple reason that she was no longer sufficiently interested.

These are only speculative suggestions attempting to understand the scope and style of Stein’s translation of Philippe Pétain’s speeches to the French. Others, I hope, will approach the same material in a different manner. For, if anything, it seems to me that “setting the record straight” when it comes to Gertrude Stein’s war years is a misnomer. She was a queer writer adept at getting by and always capable of surprising her readers; it would be interesting to see radical readings which responded to her provocation. Rather than dismissing her collaboration as purely negative, in contrast, say, to Samuel Beckett’s war years, one could, for example, place Stein’s writings for the Vichy regime beside works such as Funeral Rites by Jean Genet. Stein’s translations of Pétain’s speeches, like her other work, present a diversity of possible interpretations. If we are to understand them, we do well to reserve a priori judgments about their meaning and to pay attention to their range and peculiarity.

Quotations and the holograph reproduction from the Stein translations are used without objection from the Beinecke Library, Yale University, and the estate of Gertrude Stein.

1. Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University, MSS 76, box 64, folders 1140–1142.

2. YCAL MSS 76, box 64, folder 1139 (in English) and folder 1143 (in French translation). Stein’s introduction has been printed in Edward Burns and Ulla Dydo’s appendix to The Letters of Gertrude Stein and Thornton Wilder, ed. Edward Burns, Ulla E Dydo, and William Rice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 406–408, as well as in Modernism/modernity 3, no. 3 (September 1996): 93–96.

3. Barbara Will, Unlikely Collaboration: Gertrude Stein, Bernard Faÿ, and the Vichy Dilemma (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 138.

4. Edward Burns, “Gertrude Stein: A Complex Itinerary, 1940–1944,” Jacket2.

5. The speech with five sections, for each of which Stein begins a new page as if beginning a new speech, is dated 11 Oct. 1940. The speech was actually given on 10 Oct. 1940.

6. Philippe Pétain, Paroles aux Franc̜ais; messages et écrits, 1934–1941 (Lyon: H. Lardanchet, 1941).

7. See, e.g., Pétain, Discours aux Français, ed. Jean-Claude Barbas (Paris: Albin Michel, 1989).

8. Stein and Thornton Wilder, “Appendix IX: Gertrude Stein: September 1942–September 1944,” in Burns, Dydo, and Rice, The Letters of Gertrude Stein and Thornton Wilder, 409.

9. Will, Unlikely Collaboration,138.

10. Pétain, Discours aux Français, 73.

11. YCAL MSS 76, box 64, folder 1141, Speech 10.

12.Pétain, Discours aux Français, 76.

13. YCAL MSS 76, box 64, folder 1141, Speech 10.

14. Information on this document is available from a number of new reports describing its discovery. See, for example, the Lizzy Davies Guardian article; see also the French Wikipedia page “Lois contre les Juifs et les étrangers pendant le régime de Vichy” for a discussion with more context.

15. See, for example, Monique and Jean Paillard’s Documents secrets pour servir à la réhabilitation du maréchal Pétain (Paris: Editions du Trident: Diffusion, Librairie française, 1989). Versions of this argument are common in nonacademic writing. One made by “VSA” is available online.

16. Pétain, Discours aux Français, 99.

Appeal inform [?] of the Lorraines

French People.

Seventy thousand Lorraines have come into the free zone¨, having had to abandon everything; their houses, their goods, their villages, their church, their cemeteries where sleep their ancestors all in short that makes life worth living.

They have lost every thing, and they have come to ask sanctuary from their brethren in France. Behold them in the threshold of winter, without resources, having nothing left of wealth, except their pride in being still french[.] they accept indeed their evil plight without complaint and without recrimination. They are the french people of a great race of energetic souls with souls full of strength and valiant hearts. A great number of them are peasants. Living in the vicinity of a frontier they have throughout the centuries suffered more than all others the hardships of war. I feel as you feel yourselves all their agony suffering agony. The government is doing all in its power to comfort their misfortune to furnish them the means of living and worship. But the Lorraines deserve better; it is necessary that the feeling welcome they receive is the feeling welcome of the heart such as one shows to brothers and clansmen whom one loves. That ever one thinks of a way of showing that there where they are seat they will find a home the sweetness of a home and the gentleness comforting of the the great entire friendship of the french people.

Already there have been many offers of properties, houses, [word?] to be placed put found to the put at the disposition of the refugees. It is necessary that these shall be more and that each department which welcomes receives them should discover search out everything ways which, will can soften palliate their fate. situation. Forced to leave with little but their skin and a very small possesions, they need everything.

That every one of you make an effort to help them, to comfort them, to given them work, in all ways in which they can be employed. That all this should will be done with an ardent enthusiasm ration: underline;">in short is that they feel all about them sympathy and affection.

With this effort at helping united effort in helping our unhappy compatriots we will come not make us better and more united.

(YCAL MSS 76, box 64, folder 1142, Speech 28)

18. Stein, “Introduction to the Speeches of Marechal Petain,” Modernism/modernity 3, no. 3 (1996): 93.

22. Will, Unlikely Collaboration, 139.

23. For an excellent discussion of the complex story of this translation alongside Faÿ and Hugnet’s translations into French of The Making of Americans see Dydo, Gertrude Stein: The Language that Rises, 278–374.

24. Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), 68.

25. Will, Unlikely Collaboration, 139–40.

26. Dydo, Gertrude Stein: The Language That Rises, 1923–1934 (Evanston, Ill: Northwestern University Press, 2003), 299.

27. Stein and Wilder, “Appendix IX,” 409. The classic example is The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress (Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 1995), in which Stein’s narrator often bewails having to keep writing: “Mostly then I have to tell it” (323), “I am all unhappy in this writing” (348), “It is so very confusing that I am beginning to have in me despairing melancholy feeling” (459), “I am altogether a discouraged one. I am just now altogether a discouraged one. I am going on describing men and women” (548), “I am in desolation and my eyes are large with needing weeping and I have a flush from feverish feeling … I tell you I cannot bear it this thing that I cannot be realizing experiencing in each one being living … I am filled then with complete desolation” (729).

28. Pétain, Paroles aux Français, 41.

29. YCAL MSS 76, box 64, folder 1141, Speech 4.

30. YCAL MSS 76, box 64, folder 1142, Speech 29.

A dossier

Edited by Charles Bernstein