Far in toward the far end (PoemTalk #169)

George Quasha, 'self fast' and 'that music razors through' (preverbs)

Al Filreis convened Charles Bernstein, Anthony Elms, and Laynie Browne to talk about two poems by George Quasha. These were selected from Quasha’s most recent collection of his “preverbs.” The book, published by Spuyten Duyvil in 2020, titled Not Even Rabbits Go Down This Hole, consists of eight gatherings of preverbs; our two poems, coming from the final section — which bears the name of the book — are “self fast” (numbered 12; TEXT) and “that music razors through” (numbered 13; TEXT). The recordings we use in this episode can be found on PennSound’s extensive Quasha author page. These preverbs were recorded by Chris Funkhouser on December 27, 2017.

At some point during the conversation our group riffs on variable senses of “preverb”: a version of proverb; a preliminary saying; language that precedes verbalization; an expression prior to or independent of action; etc. Each line is a sentence. Are there juxtapositional meanings to be derived from the sequencing of the sentences? Are the lines montaged? Are they collaged? What kind of extended, project-length seriality is this? Charles at one point refers to the form of the preverbs as “prose poem.” Al believes they are meditative and even testifies to mesmerization as an effect of his one-sitting reading and listening. Anthony had a similar ecstatic experience absorbing the whole series. (Pictured above, left to right: Anthony Elms, Charles Bernstein, Laynie Browne.)

Laynie and Anthony explore the qualities of the many torqued aphorisms, whereupon Charles compares “Not mine to reason sly but to shoo or fly” with its Tennysonian original. We encounter statements of art (and of this particular form of art) — in other words, metapoetic lines — in these two  preverbs, as if to comment on the aphoristic remaking of settled thought: “There’s echo, with no original.” And: “Language has tricks it never tells you for your own good.” And: “Thinking is only the never thought.” The last of these being, surely, yet another definition of the preverb.

preverbs, as if to comment on the aphoristic remaking of settled thought: “There’s echo, with no original.” And: “Language has tricks it never tells you for your own good.” And: “Thinking is only the never thought.” The last of these being, surely, yet another definition of the preverb.

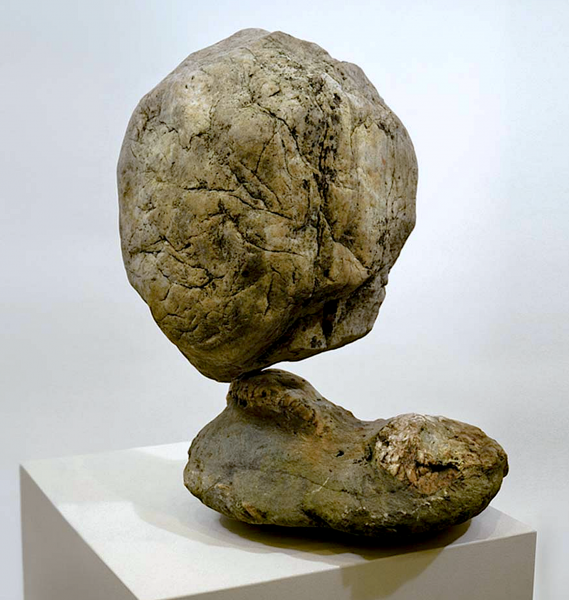

The group urges PoemTalk listeners to check out George Quasha’s artwork, including his long series of speaking portraits, “art is,” “poetry is,” “music is,” and his axial art including installations of balanced stone (sculptures called “axial stones”) and other axial objects. All this and more can be found at the Quasha web site. And then there’s Quasha’s legendary stewardship of Station Hill Press in Barrytown, NY. (Above at left: one of George Quasha’s axial stones as installed.)

George Quasha responds, in part, as follows:

[The] question as to whether the relationship between lines and “stanzas” can be expressed as collage vs. montage was very interesting – I hadn’t raised the question to myself in quite that way. As was correctly said in your exchange, both can be found to be applicable at different moments (even simultaneously, subject to angle). In thinking this helpful distinction further it occurs to me that there should be additional options to those two approaches, equally applicable without distortion—but they may not have such well thought names. The advantage in thinking this would be in avoiding the history of usage which is very rich (I enjoyed the Eisenstein reference) and possibly conditions response.A root principle for me is that the number of possible relationships between coherent elements, however distinguished, is unlimited (i.e., unanticipated by me) – perhaps one could say, like the micro-expressions that move across faces in a nuanced conversation—always fast, always consequential, but not necessarily subject to characterization separately. The point of this metaphor is that those micro-expressions certainly communicate, but not definitively; they nuance, they transition, they qualify, they enhance, they retain, and so on. I think one of the distinctions that might characterize interesting poiesis is that the discourse is previous to all clear attributes of expression (that would be a meaning of “preverb” too). The mind tries to fit its onsite understandings into categories – it’s a cognitive reflex – and a poem subtly pushes back, wiggles out, and keeps thinking in motion toward whatever (non)end. Preverbs, like a lot of poiesis, probably push that atypically further from the comfort zone of understanding—Charles and Laynie are often doing that as well in their work, it would seem. So the “methods”—collage, montage, and whatever more—are events too quick for the eye yet continuingly operative in the refining ear.Preverbs exploit the readerly need to go back over in the interest of better understanding of what just passed; that opens up mid-syntax (and middle voice), breaks time, and creates a gap for counter rhythms of further insight. It also connects to the atemporality of cognitive oscillation – an open mind event that allows what understanding might tend to qualify too early. The composition side of that is that I very often experience the arising/fitting-in lines as more gut cognition than brain.[*]

This 169th episode of PoemTalk was directed and recorded by Zach Carduner and Chelsey Zhu, and edited by Zach Carduner. Nathan and Elizabeth Leight generously help to support PoemTalk. The podcast series, inaugurated in 2007, is a collaboration with the Poetry Foundation. A shout-out to Janet Cheung of PF for her always-reliable support of our production.

_____

* Email from George Quasha to Al Filreis, Charles Bernstein, Laynie Browne, and Anthony Elms, February 19, 2022.