Without house and ground (PoemTalk #56)

Charles Reznikoff, 'Salmon and red wine' & 'During the Second World War, I was going home one night'

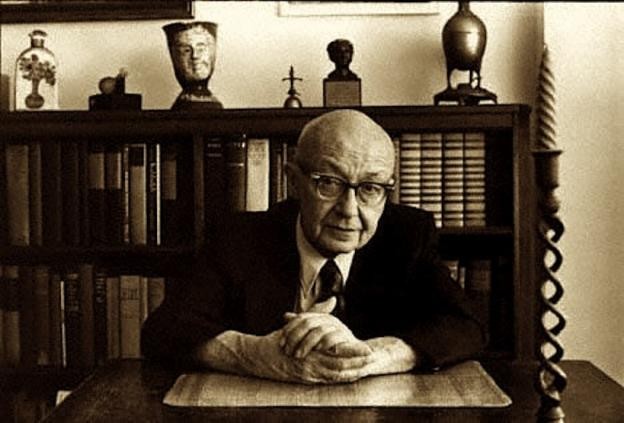

Peter Cole, Michelle Taransky, and Henry Steinberg join Al Filreis in this episode of PoemTalk to discuss two poems by Charles Reznikoff. One poem is something of an ars poetica, even though, as Peter points out, its status as metapoetry makes it an unusual effort at statement for Reznikoff, who wrote more often as he did in our second poem, which tells of — and apparently means — only what it is and tends to resist larger conclusion.

The first poem is known as “Salmon and red wine” and it appears as section 23 of Inscriptions. The second poem is known also by its first line, “During the Second World War, I was going home one night,” and it is section 28 of part 2 of a series called By the Well of Living and Seeing — a work published in 1969 in a book that brought together that series along with The Fifth Book of the Maccabees. The recording we discuss of the first poem was made at the Poetry Center of San Francisco State University in 1974, although it was written sometime between 1944 and 1956. The recording of the second poem was made when Reznikoff appeared as a guest on Susan Howe’s radio program in 1975. It is a memory of the 1940s.

“Salmon and red wine” appears in Inscriptions (p. 233) with an epigraph the four PoemTalkers discuss but which in our recording Reznikoff omitted for some reason. Here is the text of the epigraph: Thou shalt eat bread with salt and thou shalt drink water by measure, and on the ground shalt thou sleep and thou shalt live a life of trouble … — and the reference Reznikoff then gives is: Mishnah, Aboth 6:4.

“Salmon and red wine” appears in Inscriptions (p. 233) with an epigraph the four PoemTalkers discuss but which in our recording Reznikoff omitted for some reason. Here is the text of the epigraph: Thou shalt eat bread with salt and thou shalt drink water by measure, and on the ground shalt thou sleep and thou shalt live a life of trouble … — and the reference Reznikoff then gives is: Mishnah, Aboth 6:4.

The obviously important term “ground” here (and its reappearance in a different context in the poem itself) gives us plenty to discuss. “Those of us without house and ground”: who indeed are they? Are they people of the diaspora? Because “a writer of verse” is said here to require a diet of fasting and measures of water, Al — and to some extent, Michelle and Henry — wonders if the poem affirms dispossession (“without ground”) and wandering (“keep our baggage light”) as a status of necessary suffering for the sake of the modern poetic imagination. Al asks if such an understanding of the poem is “crazy” and Peter takes him up on the suggestion — it is “crazy,” says Peter — whereupon he proceeds to lead us through a discussion of how Reznikoff “is introducing poetry to a place where other people didn’t see poetry” as a function of the Mishnah’s hypergenerous offering of rules and laws and formal guidance on every quotidian act and contingency. “There’s a frame,” observes Peter of Reznikoff’s almost “conceptualist” approach. “The frame is called poetry. Everybody’s looking for it over here where ‘outlast’ and ‘blast’ rhyme. But [Reznikoff]’s saying, ‘No, no, no. Just move the frame,’ as he does in ‘the Second World War.’ And suddenly [poetry is] just ordered in a certain way.”

Al does not disagree but continues to push, seeing the Second World War poem as having something of an unconscious — a hidden or modestly suppressed knowledge of that which is not being said about loss when a Jewish poet in wartime New York City finds himself wandering into an Italian neighborhood and encounters a shopkeeper whose son has been sent to the front and who worries he’ll never return. What comparatively horrific losses are not being worried over? “We’re left to want to understand the gesture,” contends Al — when, later, the son is home safe and the shopkeeper gifts the poet a large apple in response to his plainly kind inquiry about the family. Should we read the gesture of the apple as ironic or insufficient or innocently generous? In answer to this, Michelle Taransky brought forth her teaching (from that very afternoon) of Kenneth Goldsmith’s Soliloquy, and tells us: “I would assume that Reznikoff is not turning the apple-giving into a metaphor or a moment. He’s just saying it happened. It happened just as this other thing that I didn’t write about happened.” And further: “This is just an overheard bit of conversation in the snow of conversation in New York, and Reznikoff, though he is asserting the ‘I’ here, is not saying that I’m the important ‘I’ or that I’m the only ‘I’ but that I’m an ‘I’ and this is another ‘I,’ and we’re talking.”

This episode of PoemTalk was engineered by Chris Martin and edited, as always, by Steve McLaughlin.