Fail better and revolt (PoemTalk #80)

Tom Leonard, 'Three Texts for Tape: The Revolt of Islam'

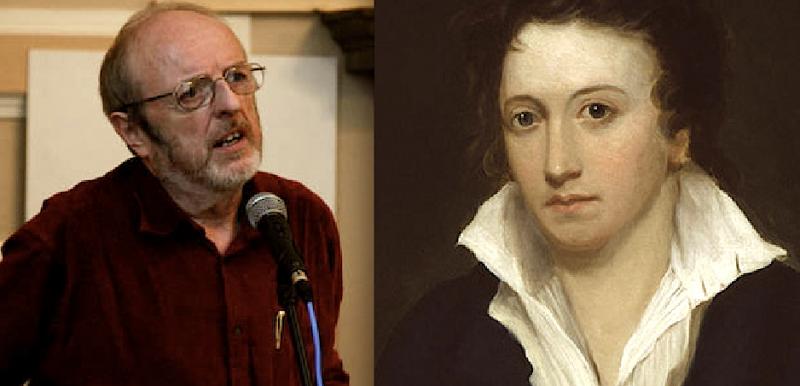

Jenn McCreary, Joe Milutis, and Leonard Schwartz (the latter two traveling from the state of Washington) joined Al Filreis at the Kelly Writers House to discuss a poem/audiotext created by the radical Scottish poet Tom Leonard. The piece is part of a work called “Three Texts for Tape,” which was recorded by Leonard at his home in Glasgow in 1978 on the poet’s TEAC A-3340S reel-to-reel tape deck. The part of the project discussed in this episode of PoemTalk is “Shelley’s ‘Revolt of Islam.’” In this piece, Leonard repeatedly — although in voices ranging across class, age, and elocutionary mode — performs stanza 22 of canto 8 of Percy Shelley’s twelve-canto, 5000-line poem.

In Shelley’s “The Revolt of Islam” Laon and Cythna incite a revolution to topple the despotic ruler of the fictional nation of Argolis, who seems to stand in for the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. It's generally agreed that the poem's narrative has nothing apparently to do with Islam in particular, but it has been read as a parable on revolutionary idealism. The PoemTalkers faced the job of trying to discern the significance of Leonard’s choice of this odd, out-of-the-way poem — and this particular stanza of such a poem — but in the course of the conversation we realized that the main issue is what Tom Leonard elsewhere has called “the diction of governance.”* The voices on the tape imply that the achievement of self-determination depends on struggling against received linguistic standards. Leonard, says Jenn McCreary, is here “looking for a way to find a voice for revolution,” in a situation where the certain sounds of certain voices remain culturally marginalized and literarily uncanonized. The stanza can be heard alternately as a prayer, an angry invocation, a vocal fumble or stutter, or the perfect incantation of an imperializing elocutioner. Thus it is far more interpretively open than would be apparent from the Shelley text without the benefit of “provincial” vocal performance. The audiowork seems in part to stand as a refusal of the effect in Scotland of formal education on the perceived value of literature. Leonard's radicalism is often — and we rather think is here, too — about the suppressions of pedagogy. He has argued, for instance, that exams have the effect of penalizing traditions of poetry for which a gradeable vocabulary of criticism has yet to be worked out. This, the PoemTalkers felt, partly or mostly explains the choice of Shelley’s distended, literarily far-flung, and narratively confusing poem — the minor work that seems directly political but turns out to be stubbornly and diffusely allegorical in its politics. But its linguistic politics seem somewhat clearer, at least to Leonard: he seems interested in affirming the connection between the Oxford English of the Oxford that expelled Shelley for refusing to repudiate authorship of writing deemed scurrilous and the Shelley who then immediately wrote a long, strident anti-monarchical poem and then eloped to Scotland.

and this particular stanza of such a poem — but in the course of the conversation we realized that the main issue is what Tom Leonard elsewhere has called “the diction of governance.”* The voices on the tape imply that the achievement of self-determination depends on struggling against received linguistic standards. Leonard, says Jenn McCreary, is here “looking for a way to find a voice for revolution,” in a situation where the certain sounds of certain voices remain culturally marginalized and literarily uncanonized. The stanza can be heard alternately as a prayer, an angry invocation, a vocal fumble or stutter, or the perfect incantation of an imperializing elocutioner. Thus it is far more interpretively open than would be apparent from the Shelley text without the benefit of “provincial” vocal performance. The audiowork seems in part to stand as a refusal of the effect in Scotland of formal education on the perceived value of literature. Leonard's radicalism is often — and we rather think is here, too — about the suppressions of pedagogy. He has argued, for instance, that exams have the effect of penalizing traditions of poetry for which a gradeable vocabulary of criticism has yet to be worked out. This, the PoemTalkers felt, partly or mostly explains the choice of Shelley’s distended, literarily far-flung, and narratively confusing poem — the minor work that seems directly political but turns out to be stubbornly and diffusely allegorical in its politics. But its linguistic politics seem somewhat clearer, at least to Leonard: he seems interested in affirming the connection between the Oxford English of the Oxford that expelled Shelley for refusing to repudiate authorship of writing deemed scurrilous and the Shelley who then immediately wrote a long, strident anti-monarchical poem and then eloped to Scotland.

Here’s the stanza of Shelley performed variously by Leonard:

“‘Reproach not thine own soul, but know thyself,

Nor hate another's crime, nor loathe thine own.

It is the dark idolatry of self,

Which, when our thoughts and actions once are gone,

Demands that man should weep, and bleed, and groan;

Oh, vacant expiation! Be at rest.—

The past is Death's, the future is thine own;

And love and joy can make the foulest breast

A paradise of flowers, where peace might build her nest.’”

Leonard’s PennSound page includes a sampling of his multi-track tape settings recorded at home in the 1970s. For this one the PennSound staff are grateful to the Archive of the Now. Our engineer for this episode of PoemTalk was Steve McLaughlin and our editor was Allison Harris.

______

*Quoted in Richard Blaustein, The Thistle and the Brier: Historical Links and Parallels between Scotland and Appalachia (2003), 142.