Biologically speaking (PoemTalk #160)

Edna St. Vincent Millay, 'Love Is Not All' and 'I Shall Forget You Presently'

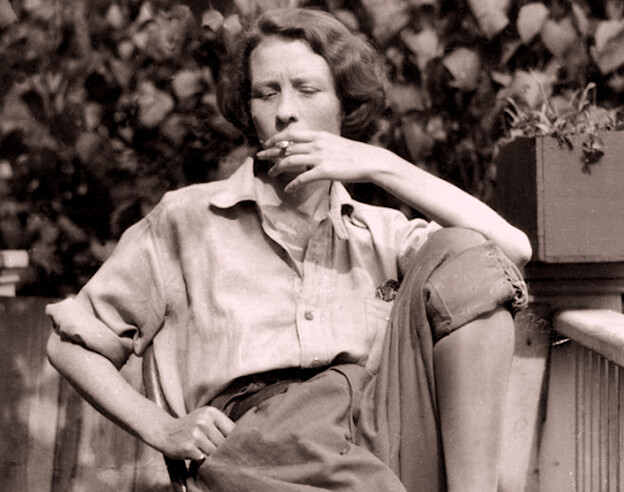

Al Filreis convened Lisa New, Jane Malcolm, and Sophia DuRose to talk about two well-known sonnets of Edna St. Vincent Millay, “I Shall Forget You Presently” and “Love Is Not All.” “I Shall Forget You Presently” became widely available as one of the four sonnets presented at the end of the book A Few Figs from Thistles (first published in 1920). “Love Is Not All” of 1931 was in Millay’s collection of fifty-two sonnets, Fatal Interview. Both poems were performed by Millay in an undated recording we include on our Millay PennSound page. We’ve made the audio available with the kind permission of Holly Peppe, Millay’s literary executor.

When Fatal Interview was published in 1931, at the beginning of the worst phase of global economic depression, some reviewers noted that at a time of deep, massive deprivation there was no place for  love sonnets.[1] At the end of our discussion, the PoemTalk group considers whether indeed, on the contrary, there is a viable political reading of “Love Is Not All.” It perhaps does convey a desperate general appetitiousness, and it ponders, more seriously than one might first notice, a willingness to sell private love for overall peace — to trade “the memory of this night for food.” A Shakespearean sonnet so modern, indeed so contemporary, as to be about subsistence, survival “in a difficult hour” of pain, bloodiness, broken bones. Millay seems to anticipate her critics’ cry for the poet’s relevance, thus outdoing them: love is not everything it’s said to be, nor is the sonnet, and truly “it is not meat nor drink.”

love sonnets.[1] At the end of our discussion, the PoemTalk group considers whether indeed, on the contrary, there is a viable political reading of “Love Is Not All.” It perhaps does convey a desperate general appetitiousness, and it ponders, more seriously than one might first notice, a willingness to sell private love for overall peace — to trade “the memory of this night for food.” A Shakespearean sonnet so modern, indeed so contemporary, as to be about subsistence, survival “in a difficult hour” of pain, bloodiness, broken bones. Millay seems to anticipate her critics’ cry for the poet’s relevance, thus outdoing them: love is not everything it’s said to be, nor is the sonnet, and truly “it is not meat nor drink.”

This episode of PoemTalk turns out to be, in essence, an hour of various considerations of the newness of modernity in relation to diction, rhetoric, rhyme, cadence, tone, and poetic form. “I shall forget you presently” is the most modern of assertions, in several senses. With delight the group observes the reversing of old social-behaviorial hierarchies (especially those describing the lives of women): first, not last, there’s forgetting; then there’s dying; and only then, the option of “moving away”! Millay, playing with values-flouting flapperism — a woman should go and move where and how she desires — sticks to the old meters, satirizing the choices they demand from within them. After all, “what we are seeking / Is idle, biologically speaking.” Listen to this podcast for a remarkable conversation about how and why a poet in the early modernist 1920s would jam into a sonnet’s final line that six-syllable meter-eating, line-consuming word: biologically. Can a sonnet be in the business of speaking biologically? Yes, according to Edna St. Vincent Millay. If poems themselves, as elaborate fictions, can be constructed of the “loveliest lie,” then everything, even biology, is up for grabs.

Zach Carduner is, as ever, PoemTalk’s director, engineer, and editor. This episode was recorded using Zoom, but is only available as an audio recording. We at PoemTalk are grateful to our partners, PennSound, the Kelly Writers House, the Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing (all at Penn), and the Poetry Foundation. We wish to thank Nathan and Elizabeth Leight for their support of our project, which began in 2007 and hereby presents its 160th episode.

NOTE

[1] Elizabeth Atkins, Edna St. Vincent Millay and Her Times (New York: Russel & Russel, 1964), 227–228.