Our endless ear (PoemTalk #124)

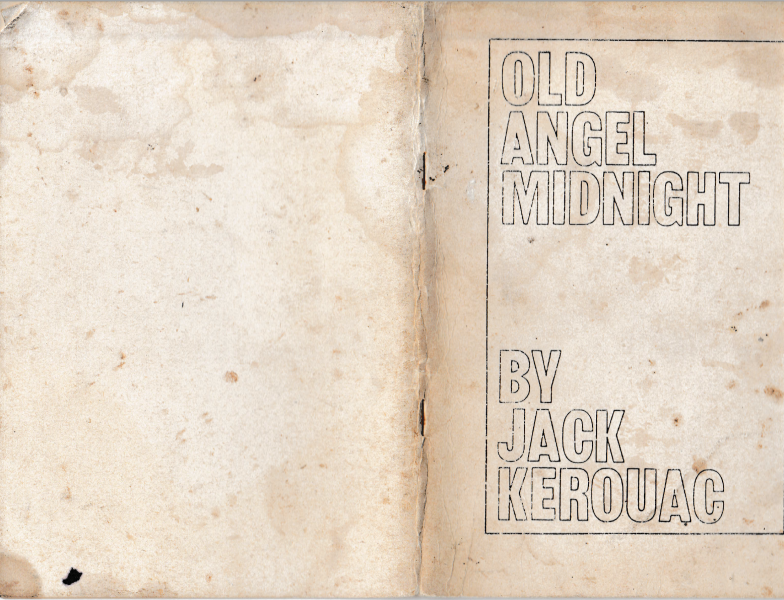

Jack Kerouac, 'Old Angel Midnight'

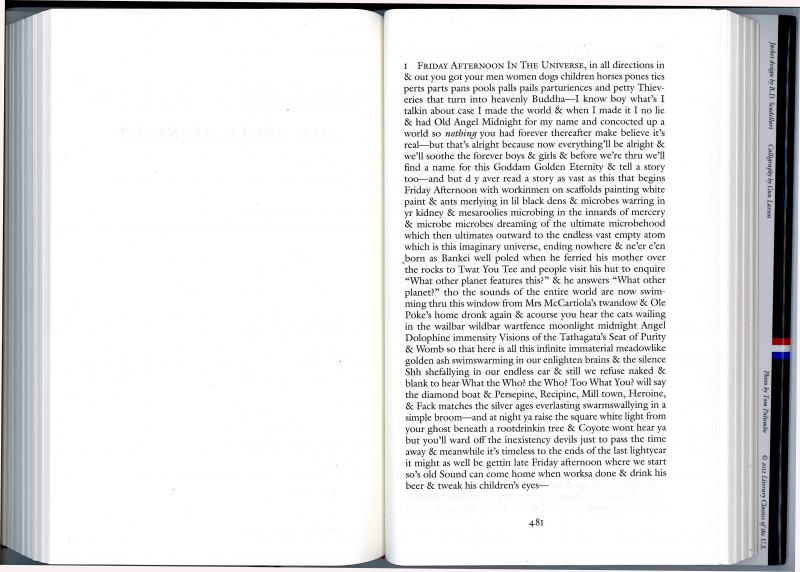

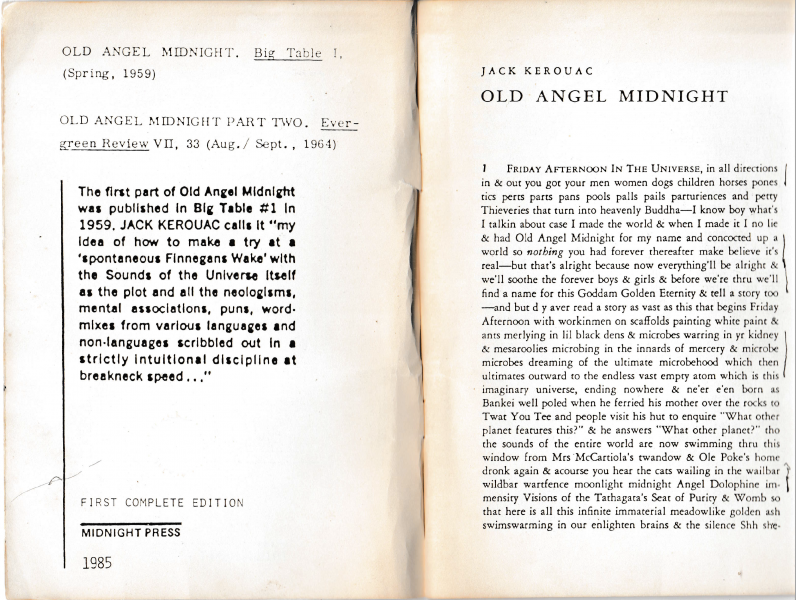

J. C. Cloutier, Michelle Taransky, and Clark Coolidge joined Al Filreis to talk about the first section (and to some extent also the fourth) of Jack Kerouac’s Old Angel Midnight, a sprawling work of prose poetry in sixty-seven numbered parts consuming forty pages of the Library of America Kerouac: Collected Poems. A recording of Kerouac performing the first page is available here. His model was Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. His initial notes were made during an extended visit to the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Up late, he listened for sounds coming through a tenement window from the court below and tried to make words out of them. Such making is the plot of the book. The effort sometimes results in what Clark Coolidge has famously called “babble flow.” Old Angel Midnight in part is a multivocal interlinguistic record of voices coming from kitchens of the other occupants in nearby apartment buildings, a man coming home drunk, etc., merged with “neologisms, mental associations, puns and wordmixes” and “nonlanguages.”

The PoemTalk group talks a good deal about the specific effects of Kerouac’s efforts to “represent […] the haddalada-babra of babbling world tongues coming in thru my window.” J. C. Cloutier admires the examination of “microbehood” as linguistics and spirituality — indicating, that is to say, both Keraouc’s fascination with languaged sound down to its smallest phonemic bits and a kind of base inner holy septicity.

The PoemTalk group talks a good deal about the specific effects of Kerouac’s efforts to “represent […] the haddalada-babra of babbling world tongues coming in thru my window.” J. C. Cloutier admires the examination of “microbehood” as linguistics and spirituality — indicating, that is to say, both Keraouc’s fascination with languaged sound down to its smallest phonemic bits and a kind of base inner holy septicity.

J. C. has worked extensively on Kerouac’s French and during this PoemTalk session provides numerous examples of the writer’s unusual usage and speaks persuasively, we think, about the importance of multilingualism to Kerouac’s poetics for Old Angel Midnight. There is inherently a mixing in representations of overheard words. J. C. is the editor of La vie est d’hommage, a collection of Kerouac’s French-language writings published in 2016 by Montreal’s Les éditions du Boréal.

In this episode Clark Coolidge continues his advocacy for Kerouac as properly belonging to the field of experimental poetry and poetics. Back in 1995, in the January/February 1995 issue of American Poetry Review, he wrote about Kerouac’s concept of time implicit in babble flow, as follows:

[S]ound is movement. It interests me that the words “momentary” and “moments” come from the same Latin: “moveo,” to move. Every statement exists in time and vanishes in time, like in alto saxophonist Eric Dolphy’s famous statement about music: “When you hear music, after it’s over it’s gone in the air, you can never capture it again.” That has gradually become more of a positive value to me, because one of the great things about the moment is that if you were there in that moment, you received that moment and there’s an intensity to a moment that can never be gone back to that is somehow more memorable. Like they used to say, “Was you there, Charlie?”

Kerouac said, “Nothing is muddy that runs in time and to laws of time.” And I can’t resist putting next to that my favorite statement by Maurice Blanchot: “One can only write if one arrives at the instant towards which one can only move through space opened up by the movement of writing.” And that’s not a paradox.

The idea of writing time as reaching a moment toward which the writing itself moves is emphasized by Michelle Taransky’s several comments about the non-narrative “story” here of the drunken neighbor (a man seemingly named Sound) arriving home on a Friday evening. As in “October in the Railroad Earth” and other experimental writings, Kerouac returns again and again to the liminality of the very end of the work week. In “Railroad Earth” it’s this: “… till the time of evening supper in homes of the railroad earth when high in the sky the magic stars ride above …” Here, in another nonsequential sundown telling, the dimly lit liminal present is always in the process of arriving. Our discussion on this point, led by Michelle, aligns with Clark’s main sourcework for conceiving of Kerouac’s improvisatory writing as a function of time — what Nathaniel Mackey and others, when exploring jazz writing, have called “a moment’s notice.”[1]