Toward a poetry and poetics of the Americas (9)

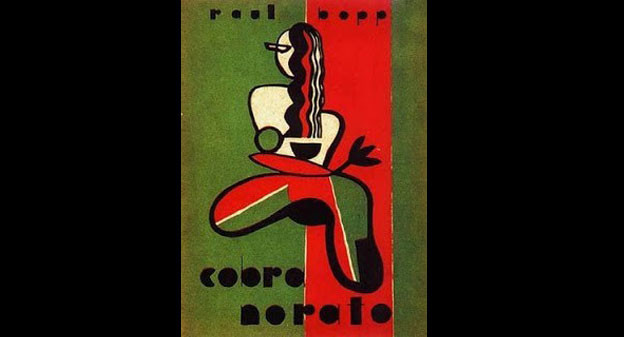

Raul Bopp, from 'Cobra Norato: Nheengatu on the Left Bank of the Amazon,' with notes by the translator

Translation from Portuguese by Jennifer Sarah Cooper

[A foundational work, along with Oswald de Andrade’s Anthropophagite Manifesto, of the Antroporfagia movement in 1920s Brazil, Bopp’s epic survives as an early example of “investigative poetry” (E. Sanders) and ethnographic surrealism (ethnopoetics). It is, as the Brazilian literary critic Othon Moacyr Garcia has it, “the one true epic poem of Brazilian literature (because of its essence rooted in the popular and for the magic of its verbal form) and one of the greatest legacies of the Modernist Movement.” The poem’s idiomatic range, carried over into Cooper’s English, is also to be noted. Or Oswald de Andrade, again, of one of the indigenous languages/cultures touched on by Bopp: “Tupi or not tupi!” which is always the question. (J.R.) To be included in “the poetry & poetics of the Americas,” a transnational anthology coedited with Heriberto Yépez, now in progress.]

I

One day

I’ll end up in the land Beyond

I light out, walking on and on

blending in the womb of the backwoods, chewing on roots

After a while

I work up a swamp-lily spell

& conjure up the Cobra Norato

“Let me tell you a story

Shall we stroll those curvy islands?

Now, imagine moonlight …”

Night comes on sweetly

Stars chat in low tones

So I wrangle a rope around the neck

& strangle the Snake.

Now that’s better

I squeeze into its elastic silk skin

& set out to travel the world

I’ll find Queen Luzia

I want to marry her daughter

Well, then, you must first close your eyes

Sleep slips over my heavy eyelids

The muddy ground robs the strength of my steps

II

And now the encrypted forest begins

Shade hides trees

Thick-lipped frogs spy in the dark

Here a wit of woods is being punished

Saplings squat in the mire

A slow slip of stream licks loam

“All I want is to see Queen Luzia’s daughter!”

Now the rivers drown

gulping the path

Water rolls by the marshes

sinking sinking

Up ahead

sand cradles the footprints of Queen Luzia’s daughter

“OOOeee,

now I’ll see her”

But first you must pass through seven doors

to see seven white women with empty wombs

guarded by an alligator

“All I want is to see Queen Luzia’s daughter!”

You must deliver your soul to Papa Legba

chant on the new moon

& drink three drops of blood

“Only if it’s the blood of Queen Luzia’s daughter”

Immense wilds with insomnia

Sleepy trees yawn

At last, the night has dried out River water crashed

I’ve got to go

I get going willy-nilly, deep in the backwoods

where ancient pregnant trees are napping

They chide me from all sides

Where’re you off to, Norato?

Here’s three sweet saplings just waiting …

“Can’t stay

Today I’ll lay with Queen Luzia’s daughter”

III

I tear off, burning sand

Pokeweed scratches me

Fat shafts play sink in the mud

Twigs pssst as I pass

Leave me alone, I got a long way to go

Nuts-sedges block the way

Oh Curupira!

Whose evil-eye has cursed me

& reversed my tracks on the ground?

I slither withered

searching for Queen Luzia’s daughter

I coil up for the night

Earth sinks away

Bog’s soft belly roll swallows me whole

Which way should I take?

My blood aches

spellbound by Queen Luzia’s daughter

IV

This is the forest of fetid breath

birthing snakes

Skinny rivers forced to work

The current bristles

peeling phlegmy banks

Toothless roots gum loam

In a flooded stretch

marsh swallows stream

Stench

The wind has moved on

A hiss frightens the trees

Silence injured itself

Up ahead a dry trunk falls:

Boom

A scream crosses the forest

Other voices arrive

River choked on a sandbank

I spy a frog frog

I smell the smell of a gentleman

“Who are you?”

“I am Cobra Norato

On my way to cozy up with Queen Luzia’s daughter”

V

They’re studying geometry

here at the trees’ school

“You’re blind from birth. You have to obey the river”

“It can’t be! We’re slaves to the river”

“You’re condemned to work forever and ever

Obliged to make leaves to blanket the forest”

“It can’t be! We’re slaves to the river”

“You must drown men in shadows

The forest is man’s enemy”

“It can’t be! We’re slaves to the river”

I cross thick walls

I hear the ayeee-help-me finches’ screeches

They’re schooling the birds

“If you don’t learn the lesson you have to be trees”

“Ayee aeeeyee aeeeyee aeyeeeee …”

“What are you doin’ up there?”

“I have to announce the moon

as it rises behind the woods”

“And you?”

“I have to wake the stars

on St. John’s night”

“And you?”

“I have to count the hours deep in the wilds”

tsrook … tsrook … tsrook … tsrook

zlit … zlit-zlit

TRANSLATOR’S NOTES

Jennifer Sarah Cooper

Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte

Natal, Brazil

Stories of the encantado, Cobra Norato, are well-known throughout Brazil. In the South largely due to this poem, but in the North and Northeast they belong to an enormous repertoire from a thriving Amazonian oral tradition in practice — which is to say, the storytelling or the relating of currently occurring phenomena. There are many versions, of course, about the origin of this encantado. In one version, registered by folklorist Câmara Cascudo in Lendas Brasileiras (1945), the snake’s mother was bathing in the river between the Trombetas and the Amazon when she gave birth to twin anacondas, whom she named Honorato and Maria. They came to be known as the Cobra Norato and Maria Caninana. Since she could not raise them in the village with her people, the pajé (shamanic healer) told her to throw them into the river, and so she did, and she raised them freely, there in nature. According to this version, the Cobra Norato was strong and good; he would wait for nightfall to turn into a man to be able to go visit his mother. Maria was the bigger and badder one who swallowed ships whole and is often conflated with the Cobra Grande. Slater (1994), specialist in Amazonian oral traditions, corroborates this fearsome version of Maria, citing how, in the stories people tell, the Cobra Grande appears “as an immense and eerie blue flame that plays upon the waters or a big, brightly lit riverboat that suggests an updated version of the native Amazonian Spirit Canoe. Sometimes, the boat is empty; on other occasions, it is packed with people in white clothing who gaze out toward shore.” (Slater, 1994, 160).

In constrast to Câmara Cascudo, however, Slater registers, in her field work (1994), the general sense of the Cobra Norato in line with another encantado of the region, the Boto Vermelho (Red River Dolphin), who sheds its animal form to turn into a fine-looking, well-dressed man or woman for the purpose of going to parties (Slater, 1994, 159). In the case of the Cobra Norato, the polymorphism is always into a man. This is the version that Bopp plays upon, in a reverse polymorphism from man into anaconda, and so the telluric character predominates as the plants, animals and encantados, and the river itself are central characters, and the Cobra Norato turns back into a fine gent to kick up some dust and down some rum just once in the rousing section XXV. This, just after the appearance of the Red River Dolphin in section XXIV.

These excerpts are the translations of the first five sections of the thirty-three-part poem by Bopp, “Cobra Norato: Nheengatu on the Left Bank of the Amazon,” which tells the journey of the speaker, who has entered the body of the Cobra Norato, as he travels down the Tapajos and Amazon rivers in search of Queen Luzia’s daughter.

It begins in the “land Beyond” — terra do Sem-fim — literally the land of without end. Sem-fim is a trickster figure similar to the Saçi Pereré of the South, who is depicted in popular stories as a one legged, pipe-smoking, sometimes red, sometimes black or brown mischief-making character. It is also an allusion to the Terra-sem-mal literally “land without evil,” to which the Tupi tribes from the south were destined when they encountered the Portuguese landing on the coast (Hill, 1995).

The object of Cobra Norato’s desire and purpose of his journey is to find the “daughter of Queen Luzia” — filha da rainha Luzia (I, line 2). Although there is no such encantado per se, Queen Luzia suggests the importance of light and Santa Lucia, the protector saint of the eyes, to the Amazonian population. According to Câmara Cascudo, the Enchanted Princess is a popular motif of northern folklore in which the Enchanted Princess is transformed into a serpent. These serpent princesses are vestiges of Moorish cycles from the Iberian Peninsula. In these cycles of stories, “the enchanted princesses return to their human form just before midnight on St. John’s night or Christmas; becoming beautiful women, they sing combing their hair with combs of gold” (Câmara Cascudo, 1979, 365, 517).

In order to enter this universe, the speaker must pass through some of its Eurocentric historical representations with the reference in II, lines 16, 17, 18, to the “seven white women.” These are the women warriors, Amazons, who Gaspar de Carvajal, a friar of the Order of Saint Dominic of Guzmán, writes of in his account of the sixteenth-century Pizarro/Orellana expedition down the Amazon River, then called the Orellana river because Orellana was said to have “discovered” it. Carvajal was supposed to have seen these women on his expedition down the big river (Carvajal, 1934).

In section V, line 20, the birds have the important task of waking the stars on “St. John’s night.” Along with its relevance to the serpent-princess motif, the festivals during the month of June, of which St. John São João is one, are important events in Brazil, especially in the North and Northeast, marked by a month of large outdoor parties, full of dancing — quadrilhas, drinking, particular foods made from corn, bonfires, and during which mock weddings are performed. These parties are bigger than Carnaval in the North and Northeast and similar to Carnaval, quadrilha dance troupes rehearse all year round to perform and compete against other troupes. The quadrilhas — literally square dancing — are lively musical street theatre productions of the story of a shotgun wedding, filled with the stock characters of the bride, the groom, their parents, the sheriff, the priest, the friends, the drunk, and other village types. Although the ritual shares some similar characteristics to the North American version of square dancing — there is a caller who indicates stock choreographies, pair work is predominate — the North and Northeastern Brazilian version is less square and more dancing. Movements are broader, faster, and there are stock characters involved to orient improvised gestures — for example, the stumbling of the town drunk, the broad gestures of the mother of the bride. Also, there is a lively call-and-response element that exceeds the North American version. The calls, while they often rely on the francophone inheritance, are also regionally adapted. For example, the caller may shout out, “Here comes the rain!” and the dancers, moaning “ohhhh” crouch down, feigning the holding of an umbrella. Or the caller may shout, “Watch out for the snake!” prompting the dancers to jump and scream “Eeeeeeee” boisterously in unison.

Ultimately, along with the encantados themselves, the poem relies on sound in the shamanic healing tradition, to which, according to Slater, these encantados are integrally linked (Slater, 1994, 160). Rothenberg’s ethnopoetics ([1968] 2017) and “total translation” (1981) — the shamanic enactment of meaning in sound — resonate with and serve as a polestar for the translation of this poem.

Câmara Cascudo, Luis. Dicionário de Folclore Brasileiro, 4th ed. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 1979.

Carvajal,Gaspar de. “Discovery of the Orellana River,” in The Discovery of the Amazon According to the Account of Friar Gaspar de Carvajal and Other Documents, ed. J. T. Medina, trans. B. T. Lee. New York, 1934, 167–235.

Hill, Jonathan. Land Without Evil: Tupi-Guarani Prophetism. Chicago: Universityof Illinois Press, 1995.

Rothenberg, Jerome. Pre-Faces & Other Writings, New Directions, 1981.

Rothenberg, Jerome. Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania,3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017.

Slater, Candace. Dance of the Dolphin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Poems and poetics