Marthe Reed: Five poems from 'Binx’s Blues,' with a note on the process

On lines from Walker Percy

(1)

still burning

sky over Gentilly

it is easily overlooked

strange island

the slightest interest

New Orleans

sags like rotten lace

behind high walls

a week before Mardi Gras

warm wind

and bearing it

the street looks tremendous

devotion

commencing to make a fire

the very sound of winter mornings

streaming with tears

the mantelpiece

an evening gown

against the darkening sky

so pleasant and easy

old world

gone to Natchez

a houseboat on Vermillion

more extraordinary

the sky

into her upturned face

her eyes

a soundless word

ample and mysterious

a litter of summers past

(2)

a fresh wind

transfigures everyone

stray bits and pieces

not distinguishable

a peculiar thing

August sunlight

streaming

in yellow bars

the mystery

of those summer afternoons

the islands in the south

going under

such a comfort

a corner of the wall

enclosed

shallow and irregular

the happiest moment

the oddness of it

Carrollton Avenue early in the evening

like a seashell

her fingers on the zinc bar

cold and briney

like a boy who has come into a place

already moved

(3)

inside the wet leaves

the smell of coffee

theTchoupitoulas docks

Negro men carry children

measuring

the flambeaux bearers

showering sparks

“Ah now!”

maskers

like crusaders

leaning forward

whole bunches of necklaces

that sail

toward us on horseback

loose in the city

the entire neighborhood

possible

somewhere

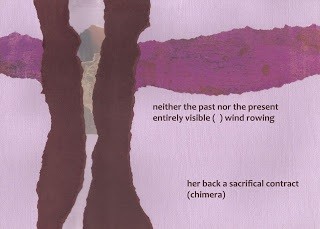

(4)

simulacrum of a dream

like a sore tooth

commoner than sparrows

celebrating the rites of spring

yellow-cotton smell

thumb-smudge over Chef Menteur

sculling

the bright upper air

the world is all sky

a broken vee

suddenly white

the tilting salient of sunlight

diesel rigs

glowing like rubies

nothing better

evenings

over Elysian Fields

who really wants to listen

in the thick singing darkness

cottonseed

in a streetcar

an accidental repetition

her woman’s despair

a little carcass

a kiss on the mouth

not even

the earth has memories of winter

(5)

the sidewalks, anyhow

virginal, as

perfect lawns

fog from the lake

seeing the footprint on the beach

a queer thing

tunneled by

new green shoots

black earth

the very words

full of pretty

snapshots

connive with me

down the levee

a drift of honeysuckle

oil cans

forget about women

the sunshine

along her thigh

the tiny fossa

saved me

facet and swell

tilting her head

far away as Eufala

WRITING SOUTH LOUISIANA, A NOTE ON THE PROCESS

Nomad, belonging accidentally and always at some remove to the places I find myself inhabiting, how root into these places, shift from being outside or between? Neither here nor there. After living eleven years in south Louisiana, drawn to the richness of its cultures, landscape, and history, painfully aware of the human brutality and environmental crises comprised therein, the sustained, willful political short-sightedness, I sought a language of place that could complicate as well as deploy the contradictory experiences of attachment and alienation without falling into the tropes of “awe/wonder”—othering the world of which we are inevitably, inextricably a part—and angry didacticism. I turned to extant texts: Florula Ludoviciana, an 1807 flora of the state first published in Paris by C. C. Robin and then in English with emendations by Constantine Rafinesque,EPA reports, reportage from the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina (2005) and the BP Oil Macondo blowout (2010), oral histories, and novels written and set in south Louisiana, among many sources. Of the latter, I drew upon Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, perhaps the quintessential novel of New Orleans, or at least white New Orleans of a particular moment, and Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, from which these pieces are derived. Attending to passages in which particulars of place were most evident, I isolated these as source-material. Cutting and juxtaposing short phrases (each line-break is an intact cut from the original) to create texts that afforded a means of writing about place, healing to a degree the otherness of my outsider status and perhaps in other ways, highlighting it, while also foregrounding language. These cut-ups move sequentially forward in the source texts and juxtapose an urban experience with a rural one. The cutting technique gave permission to write about south Louisiana, affording a way in to this place, which is simultaneously mine and not mine at all.

Poems and poetics