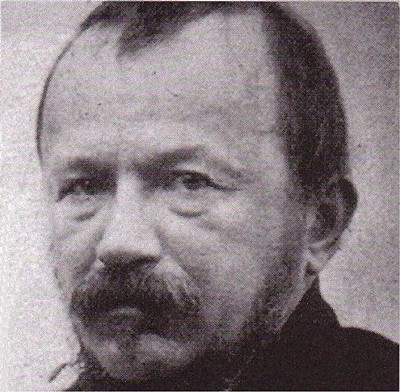

From Gérard de Nerval’s 'Les Illuminés' (1852), with a short note on the text

Translation from French by Peter Valente

[TRANSLATOR'S NOTE. Gérard de Nerval’s Les Illuminés (1852) is a collection of six essays or fictional narratives that are derived from Nerval’s own experiences. The following excerpt, which is a kind of essay on the central theme of this work, is from the concluding section, entitled “Quintus Aucler” after the man who sought to revive paganism during the ideologically unstable world of French society in the immediate aftermath of the revolution of 1789. Nerval does not portray him as a madman, but as an eccentric who was part of a larger network of religious thinkers reacting to the dwindling authority of traditional Catholicism in the late 18th century. Indeed, all the various figures in Les Illuminés come to represent a powerful undercurrent to the mainstream ideology of the time. In the excerpt, Nerval writes “There is something more frightening in history than the fall of empires, and it is the death of religions.” For him, an occult order lies below the mainstream currents of French society. Nerval writes, “the art of the revival [of paganism in the 18th century] had struck a mortal blow at the old dogma and at the holy austerity of the Church prior to the sweeping debris caused by the French Revolution.” Paganism would continue to react against the growing science of empiricism and materialim in the 19th century. And even during the darkest hour, when the gods have departed, Nerval writes, “there is still a place that remains sacred for many people.” It is not so much a specific geographical location but a psychic state. And so he reminds us that the gods are still present amidst the ruins, waiting to be invoked.

The following excerpt is from my complete translation of three parts of Nerval’s Les Illuminés (The Visionaries).]

Ψ

from Les Illuminés (The Visionaries)

There is certainly something more frightening in history than the fall of empires, and it is the death of religions. Volney [1] himself experienced this feeling when visiting the ruins of once sacred buildings. The true believer can escape this impression, but given the skepticism of our time, sometimes one shudders to meet so many dark doors opening upon nothing.

The last century still seems to lead to something – the arched doorway, the nervures and the unpolished or broken figurines that we restore with devotion, always leaves a glimpse of its graceful nave, illuminated by the magic rosettes of stained-glass windows – the believers crowd among the marble slabs and along the bleached pillars which come to depict the colored reflection of saints and angels. The incense smokes, the voices resonate, the Latin hymn soars in the vaults to the resounding noise of instruments – But let us be careful of the unhealthy breath issuing from the tombs where so many feudal kings are piled up! – A century of non-believers disturbed them of their eternal rest – those that ours so piously produced.

Never mind the broken tombs and the outraged bones of Saint-Denis! Hatred paid tribute to them; the indifferent man of today replaced them with the love of art and symmetry, as he would have arranged the mummies of an Egyptian museum.

But is it a worship that, triumphing over the efforts of the impious, still has to fear the renewal of indifference?

Where is the Catholic who would support the wild bacchanal of Newstead Abbey, or the Christmas orgy companions of Byron, parodying the plain chant with drinking songs – decked out in monastic clothes, drinking claret from skulls – content to see instead the ancient abbey become a factory or a theater? The sneer of Byron still belongs to religious sentiment, as does Shelley’s materialistic godlessness. But who today would deign to be godless? We do not think of it!

Another look into this freshly restored Basilica, the appearance of which caused these reflections – under the Gothic arches of the aisles one cannot but admire the monuments of the Medici – Angels and saints! Do you not shiver in the stiff folds of your dresses and your dalmatics,[2] witnessing the growing and prospering, right under your guardian warheads, of these pageantries of pagan art which we decorate with the name of revival? Look! The Romantic rounded arch, the marble column with bronze acanthuses, a base relief displaying its sensual nudes and accurate drawing techniques – at the foot of your long hieratic faces that irony now welcomes! Thus nothing is more true than what was said by a monk who was a prophet of the time: “ I see you, unchaste Venus, entering naked in the holy house and putting your triumphant foot on the altar!”

These three Virtues are undoubtedly the three Graces, these angels are the two lovers Eros and Anteros [3] – this beautiful woman, who rests half naked on a heightened bed and who rejects the veils, is she not Cytherea herself? And the young man next to her who seems in a deep sleep, is he not Adonis of the Syrian mysteries?

She rests having collapsed with grief, she raises her waist with that sensual delight whose posture she cannot forget, her firm breasts stand with pride, he smiles, and however near her is, the bruised hunter is asleep like a rock while his member stiffens.

Listen to the legend that the man of the Church repeats to all: “Here is the grave of Catherine de Medici. She wanted to represent her life as a long deep sleep in the same bed as her husband, Henri the second, who died suddenly from the lance of Montgomméry.”

This queen is noble and attractive with her disheveled hair – beautiful as Venus, and faithful as Artemis – and she did well not to wake up from this graceful sleep! She was still so young, so loving and so pure. But she already struck a blow at religion unintentionally – as happened in later times, during the days of saint Barthélemy. Yes, the art of the revival had struck a mortal blow at the old dogma and at the holy austerity of the Church prior to the sweeping debris caused by the French Revolution. Allegory in replacing primitive myth had done the same thing once the ancient religions…. It always ends up with a Lucian who writes the dialogues of the gods – and later, Voltaire, who mocks the gods and God himself. If it were true, in the words of a modern philosopher, that the Christian religion had scarcely more than a century to live, would it not focus with tears and with prayers on the bloody feet of this Christ untied from the mystic tree, on the spotless dress of his Virgin mother, supreme expression of the ancient covenant of heaven and earth – final kiss of the divine spirit that weeps and then flies away!

More than a century has passed already since this situation was created by men of high intelligence and found itself variously resolved. Those of our ancestors who were devoted with sincerity and courage to the emancipation of the human mind were compelled perhaps to confuse religion itself with the institutions that it adorned with ruins. They put the axe to the tree, and the heart rotten like old bark, like the thick branches, refuge of birds and bees, like the stubborn fox grape covered with vines– all were cut down at the same time – And the whole was thrown into darkness like a useless fig tree; but though the object is destroyed, there is still a place that remains sacred for many people. It is what had formerly included the victorious Church, when it built its basilicas and its chapels on the location of abolished temples.

NOTES:

[1] Constantin François de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney (February 3, 1757 – April 25, 1820) was a French philosopher, abolitionist, historian, orientalist, and politician. He travelled to the East in late 1782 and reached Ottoman Egypt where he spent nearly seven months. Afterwards, he lived for nearly two years in Greater Syria in what is today Lebanon and Israel/Palestine in order to learn Arabic. He returned to France in 1785 and spent the following two years compiling his notes and writing his Voyage en Egypte et en Syrie, which was published in 1787. One of his most interesting ideas was that the people of Ancient Egyptian Civilization were not Ayran, which conflicted with the European prejudices of the 18th century. “Just think,” de Volney declared incredulously, “that this race of Black men, today our slave and the object of our scorn, is the very race to which we owe our arts, sciences, and even the use of speech! Just imagine, finally, that it is in the midst of people who call themselves the greatest friends of liberty and humanity that one has approved the most barbarous slavery, and questioned whether Black men have the same kind of intelligence as whites!” Thomas Jefferson was at work on a translation of de Volney’s Ruins of Empire when he died.

[2] The dalmatic is a long wide-sleeved tunic, which serves as a liturgical vestment in the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican, and United Methodist churches, which is sometimes worn by a deacon at Mass or other services.

[3] The brother of Eros and the avenger of unrequited love.

Poems and poetics