Pablo Tac: On the 'Dance of the Indians' (1840)

Translation from Spanish by Lisbeth Haas

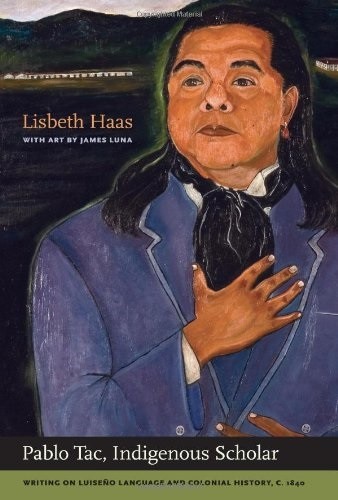

[From L. Haas, Pablo Tac, Indigenous Scholar, with art by James Luna, University of California Press, 2011.]

[NOTE. In a too short life, Pablo Tac (1820-1841) produced a rare work for his time: a completely indigenous study of Luiseño language & culture -- much more than what can be shown here. Writes Lisbeth Haas in her introduction about a work never translated or published before now: “As a historian and scholar, PabloTac defied the dominant ideas expressed about Luiseño and other indigenous people under Spanish colonialism. His work used categories of analysis such as ‘dance’ that offered an indigenous way of understanding Luiseño society during the colonial and Mexican eras in California, from 1769 to 1848. Born in Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in 1820, Tac devised a way to write Luiseño from his study of Latin grammar and Spanish, and in so doing he captured many of the relationships that existed between Luiseños during his youth. Drawing on local knowledge, traditions, and ideas, his writing leaves traces of Luiseño spiritual practice and thought, while also revealing the relations of power and authority that existed within his indigenous community.”]

All Indian peoples have their own dances, distinct from each other. In Europe they dance for joy, for festivals, or for some piece of good news. But the California Indians do not dance just for festivals but in remembrance of the grandparents, uncles and aunts, and parents now dead. Now that we are Christians, we dance ceremonially. The dance of the Yuma is almost always sad, as is their chanting, and that of the Diegueños is as well. But we San Luiseños have three principal ways only for males, because the women have other dances, two for groups of dancers, one for an individual, which is the most difficult. In the first two many can dance; one kind can be danced day and night, and the other only at night.

First Dance

No one may dance without the permission of the elders, and they must be from the same people, youths ten years of age or older. The elders, before having them dance publicly, teach them the song and make them learn it perfectly, because the dance consists of knowing the song. For it is following the song that one bows, and following the song one gives as many kicks as the little leaps made by the singers, who are the elder men, and women, and others from the same people.

When they have learned, then they can make them dance, but before that, they give them something to drink, and then that one is a dancer, and can dance and not stay behind when the others dance. Now the clothes are of feathers of various colors, and the body is painted. The chest is exposed, and from the waist hang feathers down to the knees they are covered. The arms are unclad. In the right hand, they have a wooden piece made to wipe the sweat. The face is painted, the head girded with a band of hair woven so that the cheyatom, as we call it, can go in. This cheyat is made of feathers of any bird, and almost always from crows and from hawks, and in the middle a sharp little stick that allows it to go in. Thus they are in the house, when suddenly two men go out, each of them bearing two wooden swords and shouting, without saying any word. And then, stopping in front of the place where one dances, they stand looking skyward for a while. The people go quiet, and the men return, and then out come the dancers. // We call these two men Pajaom, which means red snakes. In California there are long red snakes. They do not bite, but instead whip anyone who comes near them. // The number of dancers in this dance can grow to thirty, more or less. Emerging from the house, they turn to face the chanters and begin kicking, but not strongly, because it is not time yet, and when the chant is completed the captain of the dancers, stamping his feet, shouts hu, and they all go silent, and they make the sound of a horse in search of its colt. The word hu signified nothing in our language, but the dancers understand that it means “be quiet.” If the captain does not say hu, the singers cannot be silent, but they repeat and repeat the song as long as the captain wishes. Then they go before the singers and all the people who are watching them, and the captain of the dancers sings and dances, and the others follow him. They dance in a circle, kicking, and whoever gets tired remains in the middle of the circle, and afterwards follows the others. No one may laugh in this dance, and everyone, head bowed and eyes turned toward the earth, follows those ahead. When the dance is almost finished, everyone removes their cheyat, and holding it in their right hand, they lift it skyward, blowing out air with each kick they deliver to the earth, and the captain with one call of hu ends the dance. And everyone returns to the house where the dance regalia is kept, and then the elders begin to suck, or smoke, and they puff all the smoke skyward three times before finishing the dance. Once this is done, it is over. The elder returns to his house tired because the dance lasts three hours, and it is necessary to sing for the three hours. It is danced in the middle of the day, when the sun burns the most, and then the backs of the dancers look like water fountains with all the sweat that falls from them. This dance is difficult, and among two thousand men there was one who knew how to dance well

Second Dance

The second dance I never took pleasure in, because whoever can shout the most should shout, whoever can leap should leap, but always in keeping with the song, and it much resembles Spanish dancing. There is an old singer who has a dead tortoise with a little tick in the middle; the hands and feet, the head, and the tail are sealed, and they put little pebbles inside, and thus by moving it, it gives its sound.

And it is always danced at night. Many can dance, and when they dance, the elders throw wheat and maize at them, and here women can also dance.

Third Dance

The third is the most difficult, and that is why few are dancers of this style. In this dance one person dances. Before the dancer comes out, two men come out who are called the red serpents (as we have said). The dancer wears his pala made of feathers, from the waist to the knees; across his shoulders runs a string hung with many feathers. On his head he has a long eagle feather, and in his hands two well-formed sticks, thick as reed, and a palm and a half in length, and his whole body is painted. The circle in which he dances is eighty paces in circumference, more or less, depending on the site. Every four to seven paces, there is an elder who ensures that the dancer does not fall, which can easily happen, since he must look up at the sky, with one foot raised and the other on the ground, and with one arm in the air and the other toward the earth. So must he walk around that circle, which is made of people who want to see the dance.

Let us begin. The serpents come out, and the people go quiet, and then the singers begin singing with the cheyat and they say hu . . . . . . . . three times; we said that it signifies nothing. Then the dancer emerges and begins to run around the circle. The singers sing; he dances according to the song, as we have said, and when while dancing he comes near an elder, he tells him hu and raises his hands, and the dancer continues on his way, he can neither laugh nor speak. It is over; the elders smoke, and they return to their huts.

Poems and poetics