Unica Zürn

Nine anagrammatic poems with notes on the process by Hans Bellmer and Pierre Joris

[What follows is an attempt, once again, to cast light on the work of Unica Zürn, a fabled artist and poet, whose anagrammatic poems and automatic drawings existed on the fringe or near the center (depending on how you cut it) of post–1920s Surrealism and in close photo collaborations with German artist Hans Bellmer. The commentaries by Bellmer and poet and translator Pierre Joris, below, make a strong presentation of her principal work as a poet. (j.r.)]

IN THE DUST OF THIS LIFE

Pale sieves a tired

Ax in the tree’s bosom.

In the foliage’s broom there is

Seed-blood-silk. Bites

in the lovenest of the building.

Sweetly fogs in its ice-bath

the Ibis’s blood. Masses

in the dust of this life.

Montpellier 1955

ONCE UPON A TIME A SMALL

Once upon a time a small

warm iron was alone. No

Noise, no wine let in.

Lightly at the sea ran, while no

Ice was, thrush-pink in a

See-egg. All wink: tear

like all seeds. Sink in,

watergerm, no, alone —

in a pillow. All warmth

once upon a time’s a mall.

Montpellier 1955

AND IF THEY HAVE NOT DIED

I am yours, otherwise it escapes and

wipes us into death. Sing, burn

Sun, don’t die, sing, turn and

born, to turn and into Nothing is

never. The gone creates sense — or

not died have they and when

and when dead — they are not.

for H.B.

Berlin 1956

DANS L’ATTELAGE D’UN AUTRE AGE

(Line from a poem by Henri Michaux)

Eyes, days, door, the old country.

Eagle eyes, a thousand days old.

Ermenonville 1957

WILL I MEET YOU SOMETIME?

After three ways in the rain image

when waking your counterimage: he,

the magician. Angels weave you in

the dragonbody. Rings in the way,

long in the rain I become yours.

Ermenonville 1959

THE STRANGE ADVENTURES OF MR K

It is cold. Ravens talk around the lake. Deer

and blackbird drink tea. Raven, seer of

disaster at dusk — first stars — talk, K!

The first toad most miserably died from

Hik. Nearby the donkey-dream jawed. The

nose of poor Mr K is bleeding. Lake,

dark lake of the raven. To breathe means

to live, means climbing dreams of

rare adventures. Those, Mr. K’s?

Ile de Ré 1964

YOU’LL FIND THE SECRET IN A YOUNGCITY

Youth sings: now the sea is your harbor. Is

dream and hunt, the spirit’s inner feast, that send

him into dark, stony days, yes, you! — and he’s

immune from hand and serious sense— yes, You! Victories are

found forebodings. You travel to the city of Jim-Sing.

Go into the youngest street and find Amin, the Ti.

He says: yes, no, once, never, enemy, courage, it, are, you, D,H,G.

Secret signature? Jade stone? You’ll find the meaning.

Ile de Ré 1964

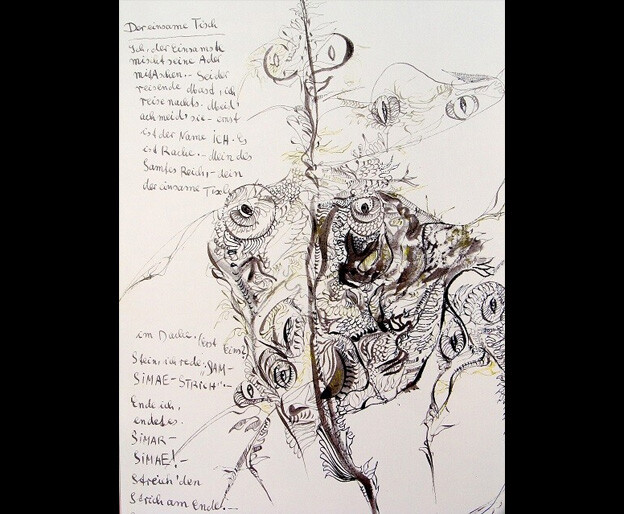

THE LONESOME TABLE

I, the most lonely

mixes his vein

with ashes. Be the

travelling mast — I

journey by night. Avoid

O avoid her, earnest

is the name I — it

is revenge. Mine the

velvet empire, yours

the lonesome table

in the roof. First one?

Stone, I speak: Sam-

Simae-line. End

I, it ends. Simar,

Simae, cross out the

line at the end. Ice

in the table. Roaring,

lonesomest I of

earth. A mast rise

up in seas and:

the lonesome table.

UNCAS, THE LAST OF THE MOHICANS

Unica’s heroes murdered — scratch

in cold earth — listen! Thank “M” —

Manitou for it, the cold hangman of

the dream of noble Aztecs. KO-HIR-

KUNAS — KIMHONA, Last One of Earth.

SUNA, the red eagle, limps. KEZ-ME,

the circling, cold anger. THU-MA,

Stone-heart and ALKAE murdered.

Uncas, the last of the Mohicans

speaks to me. Listen to him: “Cold,

sick, old is the mouth, o heart

in earth’s ore. Uncas, Thokane,

noble tomahawk of kin — ZUERN —

The last moon — it sank” (Hakirer).

Ile de Ré 1964

*

H A N S B E L L M E R : P O S T F A C E TO H E X E N T E X T E

Anagrams are words and sentences resulting from the rearrangement of the letters in a given word or sentence. It is surprising that despite the reawakened interest in the development of language in psychotics, psychics, and children, little thought has been given to the anagrammatic interpretation of the coffee grounds of letters. It is clear that we know very little of the birth and anatomy of the “image.” Man seems to know his language even less well than he knows his own body: the sentence too resembles a body which seems to invite us to decompose it, so that an infinite chain of anagrams may recompose the truth it contains.

At close inspection the anagram is seen to arise from a violent and paradoxical dilemma. It demands the highest possible tension of the form-giving will and, simultaneously, the exclusion of premeditated purposeful shaping, because of the latter’s sterility. The result acknowledges — in a slightly uncanny manner — that it owes more to the help of some “other” than to one’s own consciousness. This sense of an alien responsibility and of one’s own technical limitations — only the given letters may be used and no others can be called upon for help — leads toward a heightened flair, an unrestrained and feverish readiness for discoveries, resulting in a kind of automatism. Chance seems to play a major role in the result, as if without it no language reality were true, for only at the end, after the fact, does it — surprisingly — become clear that this result was necessary, that no other was possible. Writing one anagram each day of the year would leave one with an accurate poetic weather report concerning one’s self at the end of that year.

What is at stake here is a totally new unity of form, meaning and feeling: language-images that cannot simply be thought up or written up. They enter suddenly and for real into their interconnections, radiating multiple meanings, meandering loops lassoing neighboring sense and sound. They constitute new, multifacetted objects, resembling polyplanes made of mirrors. “Beil” (hatchet) becomes “Lieb’” (Love) and “Leib” (body), when the hurried stonehand glides over it; the wonder of it lifts us up and rides away with us on its broomstick. The process remains enigmatic. For this kind of imaging and composing to happen, no doubt an eager hobgoblin — oracularly, sometimes spectacularly — adds much of its own behind the back of the I. A pleasantly disrespectful spririt, in all probability, who is serious only about singing the praises of the improbable, of error and of chance. As if the illogical was relaxation, as if laughter was permitted while thinking, as if error was a way and chance a proof of eternity.

Translated by Pierre Joris

*

P I E R R E J O R I S: A N O T E ON T R A N S L A T I N G

U N I C A Z Ü R N’S A N A G R A M M A T I C P O E M S

Unica Zürn’s poems are extremely formal yet playful: they are anagrammatic constructs, i.e. each line is a strict transposition of the letters of a given line or phrase, usually the title line. There is of course no way in which a translator could be “faithful” to this process: s/he has to choose one of two roads: either translate the procedure and system of the poem into English, i.e. take the line or sentence Zürn used as her transformational matrix and write an English anagram based on those letters — but this would make for another poem, for the translator’s poem — or translate the resulting semantic construct. Now, what makes Zürn’s poems gripping work for the reader, is not so much the method — once one knows that she did use a specific procedure to generate her texts, a procedure, furthermore, which is obvious enough and can be described fully in English, i.e. “translated” (which is what I am doing right now) — but the meanings/images/soundings the poet is able to construct due to/despite of/with and against her chosen procedures. I have therefore chosen to translate the literal, semantic meanings Zürn arrived at, to create English language works via a method of translation that, on a certain level in relationship to the original, is as arbitrary as the original method of creation. Limits are, what any of us, etcetera …

Poems and poetics