Homero Aridjis and Pierre Joris: Two pieces on the PEN American Center Award to Charlie Hebdo

[For the record & because I’m feeling some irritation following the recent PEN Center / Charlie Hebdo brouhaha, I’m posting these two pieces on today’s Poems and Poetics. Both Joris & Aridjis have been very close to me over the years, & their pieces, taken together, provide as strong a statement as needed in the present instance. My own sense of the issues goes back to forerunners like the Dada poet Richard Huelsenbeck who spoke out against the “misbelievers” of religion & in favor of the “disbelievers” & “the liberation of the creative forces from the tutelage of the advocates of power.” “Poetry fetter'd,” as Blake had it long ago, “fetters the human race,” and the misreadings from the recent “protest” are an embarrassment & challenge for all of us who would write & think & even, as disbelievers, blaspheme freely. Or Joris, in what he writes below: “The right to blaspheme is essential for our mental health.” (J.R.)]

Is a PEN Mightier Than an AK-47?

by Homero Aridjis

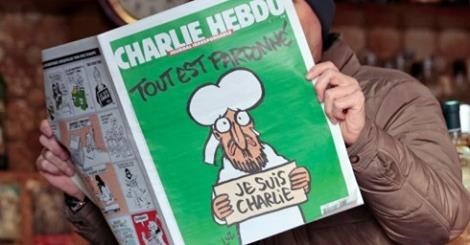

MEXICO CITY - As a former president of PEN International (1997-2003), I join Salman Rushdie and numerous colleagues in defending the PEN American Center's decision to give its Freedom of Expression Courage Award to the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo at its annual literary gala on May 5. Twelve people were murdered on Jan. 7 during an attack by two Islamist gunmen at the magazine's Paris office. A dissenting group of some 200 writers has protested the award as "enthusiastically rewarding" "expression that violates the acceptable," and some have withdrawn from acting as table hosts at the gala.

For nearly 100 years, PEN has defended freedom of speech and the thousands of professionals of the word who have been persecuted because they exercised their right to that freedom. PEN has always been quick to stand up for the victims of repressive governments, religious fanaticism or criminal groups -- be they famous writers such as Federico García Lorca (albeit too late to prevent his assassination), Arthur Koestler, Boris Pasternak, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Wole Soyinka, Orhan Pamuk and others only known locally, such as the dozens of journalists who have been attacked in Mexico during recent years.

Humor, including satire, is often lost in translation, misunderstood or only locally relevant. What would your average 1960s French intellectual have made of American stand-up comedian and social critic Lenny Bruce, whose targets often included his own Jewishness? Was Jonathan Swift's ironic A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People From Being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Publick (by selling them as food to the wealthy) received with death threats in Ireland?

Much of the satire published in the British magazine Private Eye is unintelligible to anyone not familiar with the vagaries and scandals of British public life and politics, but sufficiently stinging to provoke incessant lawsuits under Britain's particularly tricky libel laws --- but not physical assaults on the magazine's staff. I don't know of any murderous attacks on Luis Buñuel after he satirized The Last Supper as a beggars' banquet in his 1961 film "Viridiana," although the movie was denounced by the Vatican and banned in Franco's Spain.

Two French sociologists examined Charlie Hebdo's 523 covers over the past ten years and found that 336 took aim at politics, 85 were concerned with social and economic issues, 42 zeroed in on media celebrities and only 38 (that is seven percent) focused on religion, out of which 21 tweaked Catholicism, 10 dealt with several religions -- including Judaism -- together and seven were focused on Islam. Twenty-two covers were directed at a mix of subjects.

Charlie Hebdo's many and varied targets over the years certainly have included one particularly "marginalized" (to borrow the dissenting writers' word) group, comprised of homegrown or imported Islamist terrorists. In societies where freedom of expression is the norm, should this group be exempt from criticism because it responds with extreme violence to silence its detractors?

Censorship and self-censorship, wherever in the world they may occur, are forms of public and private complicity with those who practice intolerance and aggression against writers, journalists, publishers and bloggers.

As the object of repeated death threats during my PEN presidency, I can testify from personal experience that in times of violence, solidarity among writers is paramount.

Originally published May 4, 2015 in The Huffington Post.

PEN Gala: Political Correctness Gone Viral

by Pierre Joris

That a half-dozen writers would counter the PEN proposal to correctly honor Charlie Hebdo with the Toni & James Goodale Freedom of Expression Courage Award & absent themselves from the Gala is explainable. As indeed Salman Rusdhie did explain their actions, despite the use of one inaccurate word. That nearly two hundred more (PEN-members? writers? fellow-travelers of what?) would jump on the bandwagon of this “boycott” via the net is a bit more surprising & in fact profoundly irritating. Why? Obviously the vast majority of these signers do not know French, have thus not ever read Charlie Hebdo — except possibly for minor excerpts & a few rare cartoons, given that most of the anglo news media treated the whole affair back to its origins with a sense of, how to say, Victorian prissiness. A sort of Protestant puritan white-gloves-on tight-ass-ness (I can already see the Charlie cartoon!) confronted with Gallic-Rabelaisian bravado & excess. They are thus basing their judgments on pure hearsay.

Certainly these signers-on will not have followed Charlie over the years, probably most of them will never have held a single issue in their hands. Would they thus know that (as laid out below) “of the last 500 covers of the paper, no more than 30 took aim at religion? And that, of those 30, just seven—seven!—took issue with Islam? And that the two most problematic cartoons, those that unleashed, in 2006 and 2015, the worldwide explosion of criminal violence of which the massacre of January 7 was the apogee, did not attack Islam as such but rather that distortion of Islam, that insult to and caricature of Islam that is radical Islam?” Of course not — so they and the seven instigators should shut up and first do their home-work to find out what Charlie Hebdo actually is and does. They’ve all been claiming Charlie Heddo as racist, most often quoting a cover on which Christiane Taubira, minister of Justice, a woman of color, is shown as a monkey: the problem is that that image comes from…Minute, a extreme right-wing neo-fascist paper & that Charlie Hebdo was reacting against the racism of the cartoon with a drawing by Charb (one of those killed).

It’s not my favorite magazine, by a far cry, but I have seen & read a large number of issues since its inception (the founders & continuers of the mag are more or less of my generation in that we belong to the “génération ’68.”) Where I am in total agreement with the magazine is that all organized religions, & more specifically the three monotheisms, need to be caricatured, attacked, shown up for the ideological con jobs & strangleholds they are. The right to blaspheme is essential for our mental health.

To show that the emperor has no clothes is important: just think of the core regions where our world is going up in flames, or where someone is holding or selling the flamethrowers that do this job — & centrally present & involved in them you’ll find the 3 core religions, misused of course, you may say, but that misuse is the direct and logical outcome of the underlying righteousness any & all religions claim: radical Islam, gone-awry Zionism, evangelical Christianity.

Are there other ways of being critical? Yes indeed — & I may prefer them, as, in relation to radical fascistoid Islam, my translation & dissemination (on this blog) of Abdelwahab Meddeb’s book The Malady of Islam shows. Today, maybe for the first time ever, I agree with Bernard-Henri Lévy, and now take the liberty to reproduce his current column as Englished by the Daily Beast. (But if you have French also go and check out Pierre Assouline’s blogpost on the same subject. Or check Katha Pollitt’s piece in The Nation, the most accurate piece, in my judgment, on this whole affair in our press.)

Bernard-Henri Lévy: The PEN Gala and the Gall of the Boycott

Blinding ignorance is what really lies behind the statements of those PEN members who’ve attacked the decision to honor Charlie Hebdo.

The writers who have decided to boycott the PEN American Center’s annual gala in New York on Tuesday, an event at which the courage of Charlie Hebdo is to be honored, rely on five arguments.

The dissenters cannot, they say, endorse the editorial line of a publication that specializes in “criticizing Islam.”

This argument fails on two counts. It fails first because paying tribute to the courage of a team that fought to the death to defend and embody the values of freedom of expression for which PEN is supposed to stand has, by definition, nothing whatsoever to do with whether one approves or disapproves of its editorial line.

And second it fails because characterizing Charlie Hebdo as a newspaper obsessed with some strain of Islamophobia is an error that the most basic fact-checking could have dispelled: is it really necessary to point out that, of the last 500 covers of the paper, no more than 30 took aim at religion? And that, of those 30, just seven—seven!—took issue with Islam? And that the two most problematic cartoons, those that unleashed, in 2006 and 2015, the worldwide explosion of criminal violence of which the massacre of January 7 was the apogee, did not attack Islam as such but rather that distortion of Islam, that insult to and caricature of Islam that is radical Islam? That is a fact.

Nevertheless, insist 35-odd writers who believe that Charlie Hebdo has already had, as Joyce Carol Oates had the gall to utter, enough publicity, seven, even two, are too many. Especially when we are dealing with caricatures inspired (sic) by “hate” and “racism.”

This argument reveals complete ignorance about the history of a paper that has always been in the forefront of the struggle against racism, as expressed in its support for SOS Racisme in the 1990s, its organization of large democratic rallies in the early Sarkozy years, and its firing of the cartoonist Siné for anti-Semitism. It also attests to a misunderstanding of freedom of thought and of the First Amendment, as well as of the boundary that divides criticism of an idea from hostility to those who hold it; the deconstruction of dogma from calls to murder those who follow that dogma; and the gentle Cabu, who poked fun at all systems of belief and all forms of bigotry, from the former actor Dieudonné, who misses the days when the Jewish journalists he doesn’t like could be marched off to a gas chamber.

Argument number three: We accept the boundary, they say. But it is tenuous, fragile. And when you’re dealing with a community that is itself fragile and vulnerable because it still bears wounds from the humiliations of the colonial era, prudence is called for. Let us skip over this vision, itself exquisitely humiliating, of a community reduced to a bunch of simple-minded individuals punch-drunk from poverty and incapable of understanding that the famous drawing of a benevolent human prophet, an apostle of kindness and tolerance, who was frustrated that it was “hard to be loved by idiots,” did not stigmatize the prophet’s message but amplified and saved it.

This habit of consigning Muslims to the colonial past of their grandparents, of declaring that a certain segment of the French population of which “a large percentage” are “devout Muslims” (how much do the boycotters really know about this?) were “shaped by the legacy of France’s various colonial enterprises” and that this is the source of their suffering today, has one effect and one only: to distract us from the other possible causes of that suffering; to divert the attention of those sufferers from the abuses of power of, for example, imams trained in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, or Yemen; and, along the way, to ignore the very real humiliation represented by the spectacle of assassins executing courageous journalists in the name of the Quran.

The fourth argument is no less than shameful. It is the argument of arrogance. Yes, you read that right. The word was indeed spoken. As if this little newspaper, penniless from its origins, libertarian by temperament and doctrine, hostile to all forms of power and self-importance, somehow falls on the dark side of power because only one of the 12 victims (copyeditor Moustapha Ourrad) was from the community “marginalized and victimized” by the neocolonial arrogance of France. As if, in a mirror image, the assassins were somehow on the side of resistance against that power, on the side of the victimized and humiliated.

I’m sorry, American friends, but it was by the same reasoning that many Europeans hesitated, on September 11, 2001, to take the side of the 2,958 victims of the attacks carried out by 19 representatives of the “party of the humiliated” against the world capital of “imperialism.” And it is the same reasoning that I myself confronted when, the following year, I carried out my investigation into the death of Daniel Pearl, that other young hero who, like the editor of Charlie Hebdo, preferred to die on his feet rather than live on his knees but who made the mistake, in the eyes of the French equivalents of Francine Prose, Rachel Kushner, and Teju Cole, of being (i) Jewish, (ii) American, and (iii) a correspondent for a newspaper that they saw as a symbol of the reigning power.

And now for the last argument, which would be laughable if the situation were not so tragic. According to Australian novelist Peter Carey, two-time winner of the Booker Prize, PEN is called upon to defend a writer only when he or she is a victim of censorship … by a government!

By that standard, so much for essayist Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who is threatened not by the Dutch government but by the killer of Theo Van Gogh and his followers from the red mosque of Islamabad. By the same standard, must we abandon Taslima Nasreen, who has lived for 20 years under threat, not from the now secular government of Bangladesh, but from the fundamentalists hordes of the entire Indian subcontinent? And how should the writers of the United States and world have reacted if Salman Rushdie, once the Iranian government lifted its fatwa, had been seriously threatened by nongovernmental jihadists affiliated, for example, with Al Qaeda or the so-called Islamic State?

I think back to PEN’s timidity in the face of the Stalinist terror of the 1930s and the post-Stalinist terror of the 1950s.

And to the deplorable Congress of Dubrovnik of 1933, at which the predecessors of Peter Carey refused to take a position against the book-burnings in Germany.

The truth, the sad and terrible truth, is that we are once again in the midst of one of those episodes of collective blindness—or fear—of which the intellectual history of the last century gave us so many examples.

The differences are that, this time, the scene is not Europe but the United States and that the party of courage, honor, and decency seems, for the moment, to have won out.

But for how long?

Translated from the French by Steven B. Kennedy.

Poems and poetics