Toward a poetry and poetics of the Americas (36)

Gregorio de Matos, Brazil, 1636–1696: Two poems

To the Veritable Judge Belchoir da Cunha Brochado

Learn’ wis noble huma afa

>d >e >n >ble

Principle awar benig amia

Differ singular preci unshaka

>ent > ous >ble

Magnific ilustri incompara

In the worl of grave just inimita

> d >ice >ble

Much love lauds slu of applause incredi

For endeavor so much work and so tru terri

> ing > ly > ble

Render readi executions always indefatiga

Your reputa sir, true noteriet

>tion >y

In that loca that never sees da

Where from Ereb there remains only a memor

>us >y

So gracio to grant such energ

A in all thi land there is gentle glor

>s > s >y

A remote a any felicit

Translated from Portuguese by Jennifer Cooper

Soneto/Sonnet

in Portuguese and Tupi

Is there anything like seeing a Paiaia

So much inclined to be a Caramuru,

Descended from the bloodline of the tatu,

Who speaks a twisted language like Cobepá?

The female line of which is called Carima

Muqueca, pititing, caruru,

Manioc mush, wine of fermented cashew

Mangled in a mortar from Priraja

The male line of which is called the Aricobe,

Whose Cobe daughter and a pale-faced Paí

Cohabited on Passé Promontory

The white man was a Mara-u marauder

She an Indian maiden all the way from Mare;

Cobepá, Aricobé, Cobé, Paí

Translated from Portuguese by Jennifer Cooper and Jerome Rothenberg

Commentary

If you are fire why do you glow so weakly?

If you are snow why do you burn without a break?

— Gregório de Matos

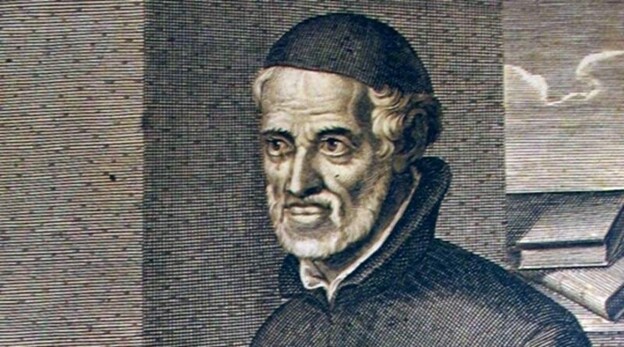

(1) [An experimental poet avant la lettre], Gregório de Matos came to be known as Boca de Inferno — “Mouth of Hell” — for his searing criticism and satire directed to the evils and hypocrisies of both the Bahian elites and the Portuguese colonial project in general. After working as a judge in Portugal for thirty years, de Matos returned to his hometown, Salvador, Brazil, where for his activities and his poetry he was banished by the colonial authorities to Angola. A year after, De Matos was allowed to go back to Brazil, where his publications were banned.

In his works — which move from the religious to the laudatory, the amorous to the pornographic — he not only criticized and caricatured the elites but registered the daily life and the language of marginalized voices, including Tupi-Guarani and Afro-Brazilian, with a burgeoning move toward a new orality.

(2) The opening piece presented here is from a group of laudatory poems, this one to the judge Belchoir da Cunha, of Bahia. The form involves a playful construction common to the anagrams and labyrinthian forms developed first in the Iberian and European Baroque. In the wordplay here, the last letters or suffixes of various words are shared from one line to the next.

In “Soneto,” the terminal words of each line are from the indigenous Tupi-Guarani and appear, as in the English version, without translation.

[Commentary by Jennifer Cooper]

N.B. Another excerpt from the assemblage of the poetry of the Americas “from origins to present,” edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Javier Taboada, is scheduled for publication by the University of California Press.

Poems and poetics