Mutsuo Takahashi: From 'Twelve Views from the Distance'

Translated from Japanese by Jeffrey Angles

In every sense, Uncle Ken’ichi seemed to have been born in order to be sacrificed to the war effort. He was born more than a decade after my father, and so the entire process of his personal development coincided with the process of Japan’s descent into conflict. In the end, his young flesh and fragile soul were placed as burnt offerings upon the altar of war.

He finished the first several years of his grade school education as class president. His grades were good enough that the principal called Grandfather in and asked him to let Ken’ichi go on to middle school, but Grandfather simply shook his head. “As soon as a day laborer’s son graduates from school, he’s gotta start working to earn some cash.” The truth is that my grandparents were not lacking the money to send my uncle to the local middle school if they had just wanted to do so.

Uncle Ken’ichi just quietly obeyed his parents. When he was quite far along in his studies, he took the test to apply to the National Railways, and he got first place. He was sent to the railway training institute at Moji for half a year before being dispatched to the railway yard at Naokata. Whenever Mother and I would pass the railway yard on the way home from town or somewhere, my uncle, who was wearing his navy blue uniform, would jump down from the line of cargo cars and wave his white gloved hand in the air for us. Mother would pick me up in her arms and make me wave back.

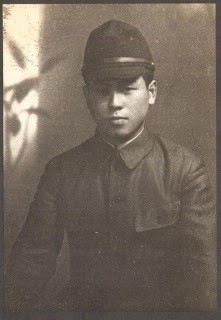

Uncle Ken’ichi was tall and had a masculine, attractive face. Such looks were unusual in our family. He was still only seventeen or eighteen, but fate — the same fate that would eventually send him to war and make him breathe his last on the battlefield — gave my uncle’s face and body the dignity of an adult. To put it differently, he was forced from his mother’s back into the cruel world, and so he had no choice but to grasp dignity for himself. I cannot see Uncle Ken’ichi as anything other than a full-fledged adult, a man who possessed a certain gloomy dignity in both flesh and soul.

* * *

I have three memories of him being sent off to war.

The first memory dates from the day before his deployment. Mother and Uncle Ken’ichi went to the photography studio in town in order to have a commemorative picture taken together. By this point, he had quit his job at the railroad and completed his preparations. All he had left was a single day, which was as precious as a jewel to him. No doubt he wanted to spend several of those final hours with Mother; that way, he could have some pleasant memories to carry with him.

He was still only seventeen or eighteen, but fate… gave my uncle’s face and body the dignity of an adult. To put it differently, he was forced from his mother’s back into the cruel world, and so he had no choice but to grasp dignity for himself.

Doing something memorable, however, was not necessarily easy. Times were rough for everyone in those days; plus, there were few places two adults might go in a country coal-mining town to do something memorable. In the end, he came up with the idea of taking a photo together. When Mother heard his suggestion, she had no reason to refuse. If anything, she was probably secretly grateful that he had come up with an idea she would have no reason to rebuff.

Dressed in his finest clothes — a slate-colored sweater with neatly pressed trousers — Uncle Ken’ichi was the first to leave the house. A little later, Mother hurriedly rushed outside. She was also wearing a slate-colored sweater and a dark gray skirt.

“Mommy, where are you going?”

She did not answer me and walked quickly away. She walked by the rowhouse where the Kawaharas and the Kanekos lived, no doubt trying to catch up with my uncle somewhere between the company housing and the Hashimoto’s house. The path went around the pond and appeared again on the other side of the Hashimoto’s. For a while I watched her and Uncle Ken’ichi hurrying along like two spring butterflies moving back and forth and tangling in the air. I watched them for the few moments before they disappeared into the shadow cast by the bank of a hill. I doubt I cried that time as I watched them go.

All I remember about the day Uncle Ken’ichi left was how sultry it was there on the platform of Naokata Station. With the scent of the crowds gathered there, it was stuffy and unpleasant. Someone had hung up a flag with the Rising Sun. People had written their best wishes for him in black ink on the white part of the flag around the red orb in the center. He was dressed in the uniform of a military recruit, and his work colleagues were also there throwing him into the air over and over again.

I stood by my grandparents while holding Mother’s hand. She was dressed in a kimono covered with a pattern of arrow feathers. I watched him and the others absentmindedly. Only when someone walking along the platform stopped as if in surprise did I indicate my pride in being connected to the specially chosen guest of honor. I did so first by looking at Uncle Ken’ichi, who was being tossed into the air, then looking back at the passersby.

The time I remember best of all was when we sent off Uncle Ken’ichi from Moji. He was departing for Niigata, where he would get on the airplane that would carry him to the battlefield. We took the Chikuhō line from Naokata, transferred at Orio, and took the Kagoshima main line to Moji, the station where the line originated. All in all, it took two and half hours to get there, so in order to see him off at nine-thirty in the morning, we had to leave Naokata at a little after five o’clock.

That was the first time in my life anyone woke me up while it was still dark. I suspect Mother and Grandmother were trying to soothe and humor me the whole way to the station. I still remember with crystal clarity rubbing my sleepy eyes and looking across the platform to see the sun rise in the sky over Mount Mitachi. The black, nighttime sky gave a strong convulsion, then the expanse of the darkness quickly became lighter as if a membrane had been peeled from its surface. There was a second convulsion. The sky grew lighter still. Once again, a third convulsion and more light. In this way, the dawn slowly broke across the sky. That was how my first dawn looked to me.

We got off of the steam-driven locomotive at Moji. There were five of us trailing along: my grandparents, Mother and I, and a young relative named Fukie who people had briefly discussed as a possible marriage prospect for Uncle Ken’ichi. As we walked, we kept asking the locals how to get to the private house where he was staying. The house was in a residential area named Kogane-machi. After a while, he came out with some of his colleagues. He was wearing a military uniform and rucksack, and at his side were his bayonet and canteen, which hung at a diagonal from his waist.

When Uncle Ken’ichi saw us, he raised his right hand to his military cap and saluted. I suspect this salute was directed more at Mother than anyone else. From there, we walked with him to the gathering place in front of the station where the military vehicles were waiting. We talked the whole way, but what was there really to talk about? I suppose that in a way, there was too much to talk about, but we did not brooch the important subjects. Instead, I believe we just stuck to unimportant exchanges, such as “Did you sleep alright?” and “Now, be careful.” I was shocked by the number of soldiers that appeared one after another from both sides of the road. The soldiers and their families filled the road to the station almost to the point of overflowing.

There was a big crowd in front of the station. They did not appear to be organized at first, but gradually they sorted themselves out. The crowd divided into two distinct groups — the military men and their families — then the military men started to congregate by platoon.

Uncle Ken’ichi said to his parents, “Stay well.” To Fukie, he just nodded. Next, he bent down and took my hand between his. “Listen to what your mommy tells you,” he said. As he held my hand between his, Mother pulled at my other hand. I wonder if the masculine warmth of Uncle Ken’ichi’s large hand didn’t travel through my small body to reach her as well… Last of all, he turned to Mother and said, “Nee-san,[1] you take care of yourself too.” Mother nodded over and over again as if she did not know what to say. He saluted us again, and grinning so that we could see his big white teeth, he turned around and joined the soldiers. He buried himself in the long line, which meandered along like a great serpent. Slowly the line disappeared into the station.

The next day, Uncle Ken’ichi was transformed into the drops of moisture on the inside of a lidded bowl. Each day, Grandmother would set an extra meal at the table for him as a way of hoping for his safe return. She would place a lid over his food, and by the end of the meal, she would look to see whether or not moisture had condensed inside. She believed this method of fortune-telling would help her know his fate.

After we received word he had left for Burma, she started using a button to tell his fortune. She would pass a string through a button and dangle it over his picture. From the swaying of the string, she could tell whether he was safe or not. Apparently, someone in the building and repairs facility taught her this far-fetched method of divination.

One night about a year later, Mother saw Uncle Ken’ichi in a dream. In it, he was wearing his army cap and saluting like on the day of his send-off. He looked like he wanted to say something, but just like after his surgery, he was only able to smile with his eyes. Right as Mother was starting to call out to him, she woke up.

The next day, Mother set out to buy some things in town. She had gone no farther than the corner of the Kanekos’ house when she came back, her face completely changed. She cried out to Grandmother, “Ken-chan is dead!” For some reason, Grandmother happened to be in the house that day. Although my mother and her mother-in-law were not always on the very best of terms, that day, they clasped one another’s hands and wept. The reconciliation brought about by the death of their shared loved one continued for some time.

Eventually the box containing Uncle Ken’ichi’s ashes arrived. The box was made of unfinished wood wrapped in bleached cotton cloth, and although his remains were supposed to be in it, the box was as light as air. Not believing it to be genuine, Mother and Grandmother opened it together. The army told us he had died of sickness on the battlefield, but inside there was nothing but two or three strands of hair.

The box was made of unfinished wood wrapped in bleached cotton cloth, and although his remains were supposed to be in it, the box was as light as air. Grandmother simply could not bring herself to give up on her only remaining son. One day, she took me to town to visit the home of one of his former colleagues who also happened to have been assigned to a neighboring platoon. The house was behind an alley off of one of the more bustling streets. We opened the latticed door and went inside. There, we found a dark concrete floor flanked on two sides by sitting rooms. The concrete floor lead into a courtyard and on the other side of that was another door. When we opened that door, we saw a sixty-year old woman using the light from the shōji to pick up some gauze bandages spread in an enamel sink. She was using a pair of disposable, wooden chopsticks to lift them to her eyes. I remember the swollen red flesh of her eyes and the thought of the disagreeably warm touch of the gauze soaked in boric acid was enough to send shivers up my spine.

Grandmother was probably thinking the old lady had received some letters from her son, and since he and Uncle Ken’ichi were once colleagues and were now in neighboring platoons, perhaps one of those letters might have mentioned him. The old lady, however, did not have any news about her own son, much less my Uncle Ken’ichi. I later heard from Grandmother that the old lady had also received word her son had also died.

The temporary reconciliation between Mother and Grandmother did not last very long. That is only natural. Both of them had completely different feelings for him, so those came to bear on the way that they thought about his death.

One quiet afternoon, I was seated on the veranda in the sun looking at a picture book. The book was about soldiers, and on the last page, one of the soldiers who was on the verge of death shouted, “His Majesty, Banzai!”[2] I asked Mother who was doing some mending nearby, “When soldiers die, do they really shout that?”

“No, what they really shout is, ‘Mother…’ But…” Mother stopped her mending and stuck the needle in her hair. I watched as she hesitated. “But I doubt Ken-chan said ‘Mother’ at the end.”

What did she mean by that? Could Mother have hoped that instead, he called out “Nee-san” as he was dying?

After that, she hardly spoke about my Uncle Ken’ichi. Her silence was probably partly out of consideration for him — a man who had passed away. In his eyes, my mother had been a virginal maiden; she had been like the sacred mother to him. In her eyes, Uncle Ken’ichi had been holy — a chaste innocent — and that was how his life ended.

Because Mother did not talk about him, his memory became an increasingly abstract principle; he became the ideal embodiment of manhood. It only helped that sometimes in an unguarded moment, Mother would slip and say, “You aren’t Uncle Ken-chan’s little boy…” No, I was not like him. In my eyes, Uncle Ken’ichi was a divine incarnation of masculine virtue who had come from the Great Beyond and returned there far too swiftly.

TRANSLATOR'S NOTES

1) Nee-san: This word means “older sister” but is sometimes used in a fashion like the word “missus” toward older women, often ones for whom one has a degree of affection but not necessarily an extremely close relationship.

-

2) Banzai: Literally “ten thousand years.” During World War II, soldiers were educated to shout, “His Majesty, Banzai!” while charging into battle.

[NOTE. Mutsuo Takahashi is one of the major postwar Japanese poets, whose work has opened up new areas of experience & expression of great importance to all of us. In Twelve Views from the Distance, published in late 2012 by University of Minnesota Press, a picture emerges of the implications of war & loss on the other side of what had been the great divide of the mid-twentieth century. Of the present book the publishers write: “From one of the foremost poets in contemporary Japan comes this entrancing memoir that traces a boy’s childhood and its intersection with the rise of the Japanese empire and World War II. In twelve chapters that revisit critical points in his boyhood, Mutsuo Takahashi re-creates the lost world that was the setting for his beginnings as a gay man and poet.” .An earlier posting of Takahashi’s poem “This World, or the Man of the Boxes, Dedicated to Joseph Cornell” appeared here on Poems and Poetics in 2011.]

Poems and poetics