Aimé Césaire: From the original version (1939) of 'Notebook of a Return to the Native Land' (29 – 37)

Translation from French by Clayton Eshleman & A. James Arnold with a Note on the Original by the Translators

29

At the end of first light, the wind of long ago—of betrayed trusts, of uncertain

evasive duty and that other dawn in Europe—arises…

30

To leave. My heart was humming with emphatic generosities. To leave… I would

arrive sleek and young in this land of mine and I would say to this land whose

loam is part of my flesh: “I have wandered for a long time and I am coming back

to the deserted hideousness of your sores.”

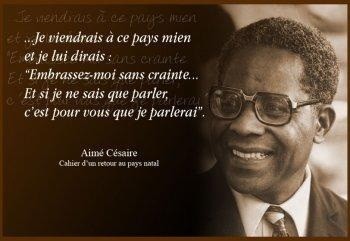

I would come to this land of mine and I would say to it: “Embrace me without

fear… And if all I can do is speak, it is for you I shall speak.”

And again I would say:

“My mouth shall be the mouth of those calamities that have no mouth, my voice

the freedom of those who break down in the prison holes of despair.”

And on the way I would say to myself:

“And above all, my body as well as my soul beware of assuming the sterile

attitude of a spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of miseries is not a

proscenium, a man screaming is not a dancing bear…”

And behold here I am come home!

31

Once again this life hobbling before me, what am I saying this life, this death,

this death without meaning or piety, this death that so pathetically falls short

of greatness, the dazzling pettiness of this death, this death hobbling from pettiness

to pettiness; these shovelfuls of petty greeds over the conquistador; these

shovelfuls of petty flunkies over the great savage; these shovelfuls of petty souls

over the three-souled Carib,*

and all these deaths futile

absurdities under the splashing of my open conscience

tragic futilities lit up by this single noctiluca

and I alone, sudden stage of this first light

where the apocalypse of monsters cavorts

then, capsized, hushes

warm election of cinders, of ruins and collapses

32

—One more thing! only one, but please make it only one; I have no right to

measure life by my sooty finger span; to reduce myself to this little ellipsoidal

nothing trembling four fingers above the line,* I a man to so overturn creation,

that I include myself between latitude and longitude!

33

At the end of first light,

the male thirst and the desire stubborn,

here I am, severed from the cool oases of brotherhood

this so modest nothing bristles with hard splinters

this too sure horizon shudders like a jailer.

34

Your last triumph, tenacious crow of Treason.

What is mine, these few thousand deathbearers who mill in the calabash of an

island and mine too the archipelago arched with an anguished desire to negate

itself, as if from maternal anxiety to protect this impossibly delicate tenuity

separating one America from the other; and these loins which secrete for Europe

the hearty liquor of a Gulf Stream, and one of the two slopes of incandescence

between which the Equator tightropewalks toward Africa. And my non-closure

island, its brave audacity standing at the stern of this Polynesia, before it,

Guadeloupe split in two down its dorsal line and equal in poverty to us, Haiti

where negritude rose for the first time* and stated that it believed in its humanity

and the funny little tail of Florida where the strangulation of a nigger is being

completed, and Africa gigantically caterpillaring up to the Hispanic foot of

Europe, its nakedness where death scythes widely.*

35

And I say to myself Bordeaux and Nantes and Liverpool

and New York and San Francisco*

not an inch of this world devoid of my fingerprint and my calcaneus on the spines

of skyscrapers and my filth in the glitter of gems!

Who can boast of being better off than I?

Virginia. Tennessee. Georgia. Alabama.

Monstrous putrefactions of revolts stymied,

marshes of putrid blood

trumpets absurdly muted

Land red, sanguineous, consanguineous land

36

What is also mine: a little cell in the Jura,* a little cell, the snow lines it with

white bars

the snow is a white jailer mounting guard before a prison

What is mine

a lone man imprisoned in whiteness

a lone man defying the white screams of white death

(TOUSSAINT, TOUSSAINT LOUVERTURE)

a man who mesmerizes the white sparrow hawk of white death

a man alone in the sterile sea of white sand

an old black man standing up to the waters of the sky

Death traces a shining circle above this man

death stars softly above his head

death breathes in the ripened cane of his arms

death gallops in the prison like a white horse

death gleams in the dark like the eyes of a cat

death hiccups like water under the Keys*

death is a struck bird

death wanes

death vacillates

death is a shy patyura*

death expires in a white pool of silence.

37

Swellings of night in the four corners of this first light

convulsions of congealed death

tenacious fate

screams erect from mute earth

the splendor of this blood will it not blast forth?

A NOTE ON THE ORIGINAL 1939 NOTEBOOK OF A RETURN TO THE NATIVE LAND

Here are nine strophes from our translation of Aimé Césaire’s 1939 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land. This 725 line poem is a work of immense cultural significance and beauty. To date commentary on it has focused on its Cold War and anticolonialist rhetoric, material that Césaire only added to the revised 1956 text which turns out to be the fourth, and until now, primarily known version of the work.

Since 1956, readers of Césaire’s masterwork have had to wrestle with what is, in effect, a palimpsest. On three occasions after the poem’s first publication in the literary journal “Volontés” on the eve of World War II, the poet revised the carefully composed original text in a new spirit and with different aims. In 1947, the Paris bookseller Brentano’s, which published in New York City during the war, brought out the first book edition of the poem with an English translation by L. Abel and Y. Goll prefaced by André Breton’s essay, “A Great Negro Poet.” A few weeks later, Bordas, in Paris, brought out a third edition based on a different (no longer extant) typescript.

Whereas the two 1947 editions were revised exclusively by the addition of new elements to heighten certain effects, the 1956 edition published by Présence africaine in Paris (until now taken to be the definitive text) excised much of the earlier additions and substituted for them blocks of text that would align the poem with the poet’s new political position, one which embraced the immediate decolonization of Africa in militant tones. Most notably the visible traces of a spiritual discourse were obliterated, and the sexual metaphors that characterized carnal passages addressing the speaker’s union with nature were replaced by new material that introduced an entirely new socialist perspective focused on the wretched of the earth.

Our intention in offering the 1939 French text of the Notebook, translated for the first time into English, is to strip away decades of rewriting that introduced an ideological purpose absent from the original. We do not claim to reveal what the poem ultimately means but rather how it was meant to be read in 1939. Reading with the poem’s first audience, so to speak, will finally permit a new generation to judge its enduring power a century after the poet’s birth.

--A.J.A and C.E, November 2012

[A bilingual edition of the original 1939 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land translated by A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman will be published by Wesleyan University Press in the spring of 2013 in conjunction with an international Césaire conference to be held on the Wesleyan campus April 5/6.]

Poems and poetics