'The Poetry of Osip Mandelstam': A radio play by Paul Celan (complete)

Translated from Celan’s German by Pierre Joris

[Reposted as a followup to Pierre Joris’s “Thoughts on Osip Mandelstam’s Birthday,” Jacket2, January 16, 2016.]

1. Speaker: In 1913 a small volume of poetry was published in St. Petersburg, entitled “The Stone.” These poems clearly carry weight; as the poets Georgij Ivanov and Nikolai Gumilev admit, one would like to have written them oneself, and yet ! these poems estrange. “Something,” remembers Sinaida Hippius who was centrally involved in the literary life back then and who had a way with words, “something had gotten into them.”

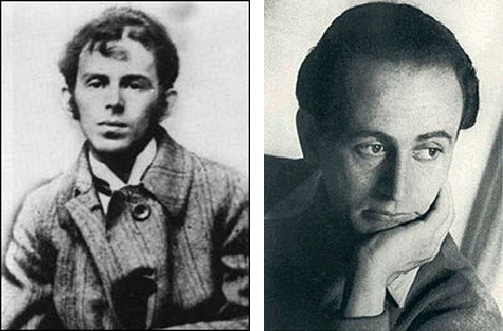

2. Speaker: Something strange — as various contemporaries report — which also applies to the author of the volume, Osip Mandelstam, born 1891 in Warsaw and who grew up in St. Petersburg and Pawlowsk and about whom it is known, among other things, that he studied philosophy in Heidelberg and is presently enamored of Greek.

1. Speaker: Something strange, somewhat uncanny, slightly absurd. Suddenly you hear him break into laughter ! on occasions where a completely other reaction is expected; he laughs much too often and much too loudly. Mandelstam is oversensitive, impulsive, unforeseeable. He is also nearly indescribably fearful: if, for example, his route leads past a police station, he’ll make a detour.

2. Speaker: And among all the major Russian poets who survive the first post-revolutionary decade — Nikolai Gumilev will be shot in 1921 as a counter-revolutionary; Velimir Khlebnikov, the great utopian of language, will die of starvation in 1922 — this “scarety cat,” anxious Osip Mandelstam will be the only defiant and uncompromising one, “the only one,” as the younger literary historian Vladimir Markov notes, “who never ate humble pie”.

1. Speaker: The twenty poems from the volume “The Stone” strike one as strange. They are not “word-music,” they are not impressionistic “mood poetry” woven together from “timbres,” no “second” reality symbolically inflating the real. Their images resist the concept of the metaphor and the emblem; their character is phenomenal. These verses, contrary to Futurism’s simultaneous expansion, are free of neologisms, word-concretions, word-destructions; they are not a new “expressive” art.

The poem in this case is the poem of the one who knows that he is speaking under the clinamen of his existence, that the language of his poem is neither “analogy” nor plain language, but language “actualized,” voiceful and voiceless simultaneously, set free under the sign of an indeed radical individuation which, however and at the same time, remains mindful of the limits imposed on it by language and of the possibilities language has opened up.

The place of the poem is a human place, “a place in the cosmos”, yes, but here, down here, in time. The poem – with all its horizons – remains a sublunar, terrestrial, creaturely phenomenon. It is the language of a singular being that has taken on form; it has objectivity and oppositeness, substance and presence. It stands into time.

2. Speaker: The thoughts of the “acmeists” or, as they also call themselves, the “Adamists,” grouped around Gumilev and his magazines “The Hyperborean” and “Apollo,” move along the same (or similar) orbits.

1. Speaker: The thoughts. But not, or only rarely, the poems themselves.

1. Speaker: “Acme”, that means the high point, maturity, the fully developed flower.

2. Speaker: Osip Mandelstam’s poem wants to develop what can be perceived and reached with the help of language and make it actual in its truth. In this sense we are permitted to understand this poet’s “Acmeism” as a language that has born fruit.

1. Speaker: These poems are the poems of someone who is perceptive and attentive, someone turned toward what becomes visible, someone addressing and questioning: these poems are a conversation. In the space of this conversation the addressed constitutes itself, becomes present, gathers itself around the I that addresses and names it. But the addressed, through naming, as it were, becomes a you, brings its otherness and strangeness into this present. Yet even in the here and now of the poem, even in this immediacy and nearness it lets its distance have its say too, it guards what is most its own: its time.

2. Speaker: It is this tension of the times, between its own and the foreign, which lends that pained-mute vibrato to a Mandelstam poem by which we recognize it. (This vibrato is everywhere: in the interval between the words and the stanza, in the “courtyards” where rhymes and assonances stand, in the punctuation. All this has semantic relevance.) Things come together, yet even in this togetherness the question of their Wherefrom and Whereto resounds – a question that “remains open,” that “does not come to any conclusion,” and points to the open and cathexable, into the empty and the free.

1. Speaker: This question is realized not only in the “thematics” of the poems; it also takes shape in the language – and that’s why it becomes a “theme” – : the word – the name! – shows a preference for noun-forms, the adjective becomes rare, the “infinitives,” the nominal forms of the verb dominate: the poem remains open to time, time can join in, time participates.

2. Speaker:A poem from the year 1910:

The listening, the finely-tensed sail.

The gaze, wide, empties itself.

The choir of midnight birds,

swimming through silence, unheard.

I have nothing, I resemble the sky.

I am the way nature is: poor.

Thus I am, free: like those midnight

voices, the flocks of birds.

You, sky, whitest of shirts,

you, moon, unsouled, I see you.

And, emptyness, your world, the strange

one, I receive, I take!

1. Speaker: A poem from the year 1911:

Mellow, measured: the horses’ hoofs.

Lantern-light – not much.

Strangers drive me. Who do know

whereto, to what end.

I am cared for, which I enjoy,

I try to sleep, I’m freezing.

Toward the beam we drive, the star,

they turn – all this rattling!

The head, rocked, I feel it burning.

The foreign hand, its soft ice.

The dark outline there, the fir trees

of which I know nothing.

2. Speaker: A poem from the year 1915:

Insomnia. Homer. Sails, taut.

I read the catalog of ships, did not get far:

The flight of cranes, the young brood’s trail

high above Hellas, once, before time and time again.

Like that crane wedge, driven into the most foreign –

The heads, imperial, God’s foam on top, humid –

You hover, you swim – whereto? If Helen wasn’t there,

Acheans, I ask you, what would Troy be worth to you?

Homer, the seas, both: love moves it all.

Who do I listen to, who do I hear? See – Homer falls silent.

The sea, with black eloquence beats this shore,

Ahead I hear it roar, it found its way here.

1. Speaker: In 1922, five years after the October revolution, “Tristia,” Mandelstam’s second volume of poems comes out.

The poet ! the man for whom language is everything, origin and fate ! is in exile with his language, “among the Scythians.” “He has” ! and the whole cycle is tuned to this, the first line of the title poem ! “he has learned to take leave ! a science”.

Mandelstam, like most Russian poets – like Blok, Bryusov, Bely, Khlebnikov, Mayakovsky, Esenin– welcomed the revolution. His socialism is a socialism with an ethico-religious stamp; it comes via Herzen, Mihkaylovsky, Kropotkin. It is not by chance that in the years before the revolution the poet was involved with the writings of the Chaadaevs, Leontievs, Rozanovs and Gershenzons. Politically he is close to the party of the Left Social Revolutionaries. For him — and this evinces a chiliastic character particular to Russian thought — revolution is the dawn of the other, the uprising of those below, the exaltation of the creature — an upheaval of downright cosmic proportions. It unhinges the world.

2. Speaker:

Let us praise the freedom dawning here

this great, this dawn-year.

Submerged, the great forest of creels

into waternights, as none had been.

Into darkness, deaf and dense you reel,

you, people, you: sun-and-tribunal.0,05c hoch

The yoke of fate, brothers, sing it

which he who leads the people carries in tears.

The yoke of power and darkenings,

the burden that throws us to the ground.

Who, oh time, has a heart, hears with it, understands:

he hears your ship, time, that founders.

There, battle-ready, the phalanx – there, the swallows!

We linked them together, and – you see it:

The sun – invisible. The elements, all

alive, bird-voiced, underway.

The net, the dusk: dense. Nothing glimmers.

The sun – invisible. The earth swims.0,05c hoch

Well, we’ll try it: turn that rudder around!

It grates, it grinds, you leftists – come on, rip it around!

The earth swims. You men, take courage, once more!

We plough the seas, we break up the seas.

And to think, Lethe, even when your frost pierces us:

To us earth was worth ten heavens.

1. Speaker: The horizons are darkening – leave-taking takes pride of place, expectations wane, memory reigns on the fields of time. For Mandelstam, Jewishness belongs to what is remembered:

This night: unamendable,

with you: light, nonetheless.

Suns, black, that flare up

before Jerusalem.0,05c hoch

Suns, yellow: greater fright –

sleep, hushaby.

Bright Jewish home: they bury

my mother dear.

No longer priesterly,

robbed of grace and salvation,

they sing a woman’s dust

out of the world, in the light.

Jews’ voices, silent they kept not,

mother, how loud it sounded.

I wake up in my cot

by a black sun, surrounded.

2. Speaker: In 1928 a further volume of poems appears – the last one. A new collection joins the two previous ones also gathered here. “No more breath – the firmament swarms with maggots” – : this line opens the cycle. The question about the wherefrom becomes more urgent, more desperate – the poetry – in one of his essays he calls it a plough – tears open the abyssal strata of time, the “black earth of time” appears on the surface. The eye, talking with the perceived, and pained, develops a new ability: it becomes visionary: it accompanies the poem into its underground. The poem writes itself toward an other, a “strangest” time.

1. Speaker: 1 JANUARY1924

Whoever kisses time’s sore brow

will often, like a son, think tenderly

how she, time, laid down to sleep outside

in high heaped wheat drifts, in the corn.

Whoever has raised the century’s eyelid

– both slumber-apples, large and heavy – ,

hears noise, hears the streams roar

the lying times, relentlessly

Imperious century, with loam-beautiful mouth

and two apples, asleep – yet

before it dies: to the son’s hand, so shrunken,

it bends down its lip.

Life’s breath, I know, ebbs away each day,

one more small one, a small one – and

deceased is the song of mortification, loam and plague,

with lead they seal your mouth.

Oh loam-and -life! Oh centrury’s death!

Only to the one, I’m afraid, does its meaning reveal itself,

in whom there was a smile, helpless – to the inheritor,

the man who lost himself.

Oh pain, oh to search for the lost word.

oh lid and lid to raise, sick and weak,

for generations, the strangest, with lime in your blood

to gather the grass and the weed of night!

Time. The lime in the blood of the sick son

turns hard. Moscow, that wooden coffer, sleeps.

Time, the sovereign. And no escape anywhere...

The snow’s apple-scent, as always.

The sill here: I wish I could leave it.

Whereto? The street – darkness.

And, as if it were salt, so white, there on the pavement

lies my conscience, spread out before me.

Through winding lanes, through slipways

the journey goes, somehow:

a bad passenger sits in a sled,

pulls a blanket over the knees.

The lanes, the shimmering lanes, the by-lanes

the runners crunch’s like apples under the tooth.

The strap, I can’t grab it,

it doesn’t want me to, and the hand is clammy.

Night, carwoman, with what scrap and iron

are you rolling through Moscow?

Fish thud here, and there, from pink houses,

it steams toward you – scalegold!

Moscow, anew. Ah, I greet you, once more!

Forgive, excuse – my misery wasn’t very great.

I like to call them, as always, my brethren:

the pike’s saying and the hard frost!

The snow in the pharmacy’s raspberry light...

A clattering, from afar, an Underwood...

The coachman’s back... the roadway, blown away...

What more do you want? They won’t kill you.

Winter – beauty. And skyward the white,

the starmilk – it streams, streams away and blinks.

The horsehair blanket crunches along the icy

runners – the horsehair blanket sings!

The little lanes, smoking, the petroleum, always – :

swallowed by snow, raspberry colored.

They hear the Soviet-sonatina jingle,

remember the year twenty.

Does it make me swear and damn?

– The frost’s apple-scent, again –

Oh oath that I swore to the fourth estate!

Oh my promise, heavy with tears!

Oh whom will you kill? Whom will you praise?

And what lie, tell me, are you going to make up?

Tear off this cartilage, the keys of the machine:

the pike’s bones you lay open.

The lime in the blood of the sick son: it fades.

A laughter, blissful, frees itself –

Sonatas, powerful... The little sonatina

of the typewriter – : only its shadow!

2. Speaker: That’s how to escape contingency: through laughter. Through what we know as the poet’s “senseless” laughter – through the absurd. And on the way there what does appear – mankind is absent – has answered: the horsehair blanket has sung.

Poems are sketches for Being: the poet lives according to them.

In the thirties Osip Mandelstam is caught in the “purges.” The road leads to Siberia, where we lose his trace.

In one of his last publications, “Journey to Armenia,” published in 1932 in the Leningrad magazine “Swesda,” we also find notes on the matters of poetry. In one of these notes Mandelstam remembers his preference for the Latin Gerund.

The Gerund ! that is the present participle of the passive form of the future.

Poems and poetics