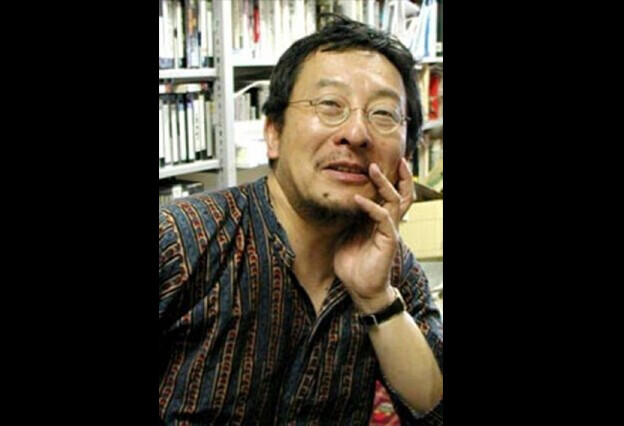

Inuhiko Yomota

from 'A Beggar of Life,' title poem translated by Hiroaki Sato

[For many years now Hiroaki Sato has brought the work of a range of Japanese experimental modernists into English, among the latest of whom is Inuhiko Yomota, whose book My Purgatory was published in 2015 by Red Moon Press in Virginia. Sato describes Yomota, a prolific writer in many areas, as follows: “Inuhiko Yomota (b. 1953) aptly calls himself a tuttologista. One of the most prolific Japanese writers on a wide variety of subjects and the most internationally encompassing, Yomota has published more than one hundred books covering Japanese film, Asian film, literary criticism, autobiography, arts, music, city theory, cooking, and manga, among other things.” And Geoffrey O’Brien of Yomota’s amazing breadth and scope: “Inuhiko Yomota … has written … a somber, passionate, highly colored cycle of poems, imbued with intimations of ancient suffering and modern-day apocalyptic terror, and candidly confronting the prospect of personal annihilation. The book’s tragic themes are offset by a bracing and defiant bravura, inhabiting different eras and identities, passing ghostlike through Carthage and Harbin and archaic Thrace, and conjuring with awed detachment the bloody and inextricable histories embedded in millennia of continually resonating language.” The following from a larger work now in progress is a still further indication of Yomota’s and Sato’s latterday gift to us. (J.R.)]

A Beggar of Life

1

I climb the Mount of Purgatory.

No longer, unlike Dante,

do I have the stars’ protection or the Holy Woman’s consolation,

but over the barren field of igneous rocks

do I see only

discarded condoms and plastic bottles

like the jellyfish washed up on the shore.

What thou lovest well remains,

the rest is dross. …[1]

Believing stupidly in this old-fashioned monitory,

I’ve lost many things.

Neither the moon I thought I’d sealed in a plastic bag,

nor the Arabic I learned by mouth to mouth, nor smiles

remain any longer.

Where in the world have I wandered into?

This fearful mountain peak —

what is it called?

Birds’ voices had ceased long ago.[2]

I climb the mountain strewn with rubble —

will there be somewhere

a fountain waiting for me?

Is there going to be a rivulet

where I can immerse my tottering feet

soiled with dust, covered with blisters?

2

I’m going to England, now.

I can think of nothing but to go to England,

you said.

I didn’t respond one way or another,

and you declared with serious eyes,

I’m going there to find a green fuse.[3]

Your mascara was swaying.

So

we decided to exchange our most favorite records.

When I offered Nico’s Banana,[4]

you came back with Bowie’s Low.

There was no hesitation.

The solemn ritual was over in a second.

There was no pledge, no promise.

You then beat your debts at several hatters

and rushed out.

Wait. Was it The Rolling Stones that I exchanged?

Was it the unpaid bills at the dentist that you beat?

When time has passed,

images of things collapse into haziness.

A spectacle that couldn’t have happened

feels like a gruesome fate

or what you must have chiseled into your heart

dissipates, before you know it,

like a perfume bottle left without its cap.

The heart slowly wears out.

Death arrives

long after that.

You will not extend your hand again

to the piles of records

in the attic where rats’ droppings scatter.

Whether you ever discovered a green fuse,

I will never know, ever.

When, in what way, shall we meet

the news of each other’s death?

3

In Payatas[5]

I was watching people dug out

of collapsed grit and dirt after the rain.

Black sand had swarmed into the open mouths

and eye-sockets.

Everyone’s eyes were closed quietly.

Rats scurried incessantly all around.

Pain and grief

nibbled me like rats.

There were times when you believed anything.

Soon feeling not moved became the only salvation.

Everyone was praying under the roofs with stones lined up on them.

But I couldn’t pray.

Praying had been exiled out of me.

Then, invited,

I went to eat a goat just slaughtered.

Hands soiled black to the tips of their nails

stretched one after another into the pot and grabbed the entrails.

I, too, was slurping the juices covered with foam and ashes.

I was eating my own entrails.

A snow-white moon rose in the shadow of a deep-black mountain.

In the distance pigs squealed.

Children, sensing the arrival of the last truck,

alertly ran up in the smoke,

vying barefoot, scattering the rats.

Is there any more mountain to climb?

I cannot ascertain it.

In the foul steam rising

rats’ sharp pointed teeth gleaming white

restlessly chisel my flesh.

I no longer even grab at my memory.

4

Who does Cordelia? It’s you.

I can do only Mad Tom.[6]

In this cold, busy-looking new century

a dignified, old king is no more

and stingy elder sisters are all gone.

Against the hastily made plywood backdrop

Cordelia says to the madman:

Learn about the stars, even in prison,

know the stars that will protect you.

But the madman does not believe it.

All stars are just corpses of light.

This is my latest work.

I’ll continue to write

until my worn-out pencil

becomes so short it can’t write any more,

until my fingers rub on the paper.

Wearing-out is my very sign.

We are the only ones who have survived.

Nevertheless, just as you cannot read my poem,

I cannot recognize your star in the night sky.

I climb the black mountain of grit and dirt,

feet tripped by rats —

where will you be watching me?

Cordelia, your magically fake eyelashes,

your silver foil hat gleaming with beads.

[An earlier selection of Sato’s translations from Yomota can be found here on Poems and Poetics.]

2. John Keats, “La Belle Dame Sans Merci.”

3. Dylan Thomas, “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower.”

4. The album of the musical band Velvet Underground and Nico with a banana on the cover designed by Andy Warhol in 1967.

5. A huge dumpsite in Quezon in the Philippines. On July 20, 2000, a landslide killed five hundred people.

Poems and poetics