David-Baptiste Chirot

'Hidden in plain sight': found visual/sound poetries of feeling eyes and seeing hands

[Himself on the cusp between “outside” and “inside” poetry and art, Chirot, whose work, both verbal and visual, is a great, too-often hidden resource, wrote from an authoritative if barely visible position in contemporary letters. The depth and breadth of his total oeuvre — the rubbings and collages foremost — is outstanding.

What we have posted here, in the shadow of his recent death, is a deeply personalized yet far-reaching poetics and a testimony to his life as an artist and poet. More of the visual and verbovisual work (rubbings and collages) can be seen at LIGHT REMAINS — NOT FADE AWAY | Flickr (J.R.)]

for Petra and for my children

If you would create, relax before moldy, wet walls and feel form shaping out of the chaotic patterns.— Michelangelo

The most beautiful world is a heap of rubbish tossed down in confusion. — Heraclitus

A final glossary, therefore, cannot be made of words whose intentions are fugitive. — William S. Burroughs

All of this happened when I was walking about starving in Christiana, that strange city which no one leaves before it has set its mark on him. — Knut Hamsun, Hunger

The same subject seen from a different angle gives a subject for study of the very highest interest, and so varied that I think I could be occupied for months without changing my place, simply bending a little more to the right or left. — Paul Cezanne

Sembrar la memoria / To sow memory — Bob Cobbing and Waldemar Niedzwiecki

——

“The real war will never get written in the books,” writes Walt Whitman at the end of the Civil War sections in his Specimen Days. “The real life” of my life isn’t written here any more than “the real war” is written in books. What I give are some stories of how I learned some methods in the “art of looking” and its companion, the art of survival. These methods go into the making of the works.

The real story is in the works themselves, though I hope these stories are of interest and use on their own. After all, if wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t be writing this right now. I might be a race car driver or an astronomer, as I wanted to be at age ten. In an old-fashioned manner, then, we begin with childhood and its relation to the present.

In The Painter of Modern Life, Baudelaire writes: “But genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will … consider [the artist] … as a man-child, as a man who is never for a moment without the genius of childhood — a genius for which no aspect of life has become stale.”

I’m leaving genius out of this, it’s childhood recovered that keeps fresh the story of one’s artist life in working with what childhood discovered.

Through time and work one finds how consistent and insistent the basic elements have been, how intricate their rearrangements. Every day the childhood eyes and hands meet those of the present, a shock of recognition occurs, and one is finding all over again things hidden in plain sight, seen as if for the first time.

Childhood is my source for the basic elements of the found and the physical. The found materials exist in the physical world and incite ideas and imaginations in their use and arrangements.

I lived a lot with my grandparents when a small child. My grandfather and godfather, Jean (John, “JT”) Trepanier, would come home from his steamfitter’s construction site work with variously sized pipes and pieces of steel, copper, and aluminum. This detritus of the day he’d use to make everything from crucifixes and chokers with JFK half dollars to merry-go-rounds, go-carts, rickshaws, birdhouses.

Some nights after dinner he’d drive me back to his work sites with him. His shiny, always well-polished Chevrolet’s dashboard had shrines and his welded medallions of the Madonna, St. Christopher, St. Jean Baptiste, and Christ Jesus. An immense revolving compass blinking in sun’s rays kept watch among them. The idea that shrines could be anywhere — and go anywhere — made a great impression on me. To this day I make “shrines” of found materials, with their own imageries and invocations.

Grandpa would proudly show the day’s work and demonstrate how to find yet more useful pieces of metal. The construction site became alive with possibilities, as alive as a forest or fields, and as filled with a consciousness of presences at eyes’ perimeters. To this day I am obsessively drawn to construction sites and finding materials to work with in various media. It’s a way to say hello to and to thank my grandfather. The sites are shrines — and mines — to me of his living on in me in my life and work.

When I was nine, my parents purchased a house built originally as two plus a shed that had been pushed all together. It was an eighteenth-century Vermont structure in rough condition. Tearing out the cheap plaster, lathe, and rat wood to get to old beams and walls, we’d found we’d need lot of good wood and bricks to rebuild from the inside. There were some old long-abandoned houses nearby and my mother, brother, and I began hauling away doors, windows, widow’s walks, thick boards, and ancient bricks and stones for paths and chimneys. My mother showed us what to keep an eye out for, how to find the best kinds of wood and brick, old glass, tools, and nameless objects with lost purposes of powerful raw beauty. The greatest thrill was to drag home by our hands and in our wheelbarrow loads of wood and stone, then to see them used in creating a new home inside the old shell. The rearrangements of these materials as old as our house made things and house “new,” hence my love for a Pascal quote I use often: “It is not the elements which are new, but the order of their rearrangement.”

Another immense glory was to go to the vehicle junkyard one of the Cook family clan had in his cow pasture. The cows grazed on tall grass rising through rusted truck chassis, and chickens roosted in car interiors. For two dollars or so we’d haul home dashboards, steering wheels, engine parts, a battered seat, and create spaceships, “cars of the future,” time machines.

One of the greatest events of all was finding a large crow’s nest lying in the road running along the edges of a forest, blown down by winds signaling a coming storm. The roomy interior was lined with strips of foil, bright cigarette packets, shiny coins, bits of glass, fragments of cloth, buttons, ticket stubs, wiring, chips of plastic and china, shreds of garish newspaper ads, and, most startling of all, the crowning jewel, a Dinky Toy luxury car nestled intact among woven dried grasses and glittering junk. A vivid example of collage and bricolage that revealed a vision of combining natural and industrial elements in creating a home, a space in the world, made of found elements.

The crow’s use of texts it could not read but valued for their letters’ bright forms and colors revealed written language as an element among others, simultaneously “readable” and “unreadable.” Just learning to read myself, this fired my imagination in the same way hieroglyphs and calli-pictographic scripts did — recognizably writing, yet beyond fixed meanings known to me. It kept alive the childhood apprehension of all forms as writings, signs, and alphabets. The sense of disappointed confinement one felt in discovering there were only twenty-six letters was done away with again.

These experiences are the childhood recovered I use daily in finding and working with materials. The huge part the physical and found play for me begins in “the genius of childhood … for which no aspect has become stale.” The importance of this aspect is its questioning of imprisonments of the “art of looking.” To see things fresh is a key to freedom’s desiring.

In “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects,” Robert Smithson writes:

A great artist can make art by simply casting a glance. A set of glances could be as solid as any thing or place, but the society continues to cheat the artist out of his “art of looking” by valuing only “art objects.” Any critic who devalues the time of the artist is the enemy of art and the artist.

Paradoxically, developing through time this “art of looking,” of seeing fresh the possibilities of openings of freedom, brings a more acute awareness of their imprisonments. The powers, processes, and possessiveness which seek to make of the artist and the “art of looking” an object, a label, a category, ultimately a corpse, are ever more visible.

Developing the “art of looking” and “childhood recovered” is a way of learning survival, “thinking on one’s feet,” and learning to camouflage oneself in the manner of the things one finds hidden in plain sight.

My first experience of living in cities was in Paris as a teenager living in the streets, abandoned buildings, parks, all-night cafes, and cinemas. The ways of seeing and walking learned in the country one puts to use in learning the languages of the street. The acceleration, concentration, and profusion of sensory experiences in the city can be worked with by using the varying speeds of languages and looking of the city and country working together. One illuminates the other.

To apprehend events and signs occurring at great speeds, one learns methods of slowing perception within time. To learn to see within time in varying speeds is to begin to alter the senses of space. Each method one finds and develops through practice is another way of opening what at first appears to be confining. The continual drive and direction of working on and with methods of seeing in time to open space — and vice versa — is the desire for freedom.

Walking in the country and cities I have lived in is the basis of speed I use. I have never had a driver’s license, so walking, except for public transportation and the occasional ride, is the first factor in an “art of looking” for me. Due to a bone disease, I couldn’t walk for almost three years at one point. For seven years, due to a broken back, walking more than a few blocks at a time was almost impossible. These periods of deprivation make each day of walking fresh, an experience of freedom. Not taking it for granted opened my eyes to not taking for granted the things seen and heard in the world. Everything takes on an interest and use because it isn’t “ordinary.”

The effect of this has been to continually widen awareness of the “hidden in plain sight” of the physical and found.

Another effect of physical limits I use in developing an “art of looking” is due to my back being broken three times. Since I can’t turn very much at the back and shoulders, at first unconsciously and then consciously I’ve developed an awareness and use of shadows and any mirroring surface — they are far more plentiful than you’d think — to see what is behind me or to an extreme side angle. That’s opened up more “avenues” to find and work with.

Walking in the streets generates an energy and speed of the “art of looking” that refuses the conventional limits of “art production” and “art objects.” Smithson’s “time of the artist” can alter itself and its speeds in many ways, including disruptions in the “system of production.” Paul Virilio in Speed and Politics writes:

The revolutionary contingent attains its ideal form not in the place of production, but in the street, where for a moment it stops being a cog in the technical machine and itself becomes a motor (machine of attack), in other words, a producer of speed.

Living in the streets of Paris in 1969 and 1970, where the aftereffects of May ’68 were still powerfully felt (I lived in Arles in 1967–68), deeply affected my ways of seeing and thinking. The interrelationships among street life and action — “propaganda of the deed,” graffiti, making posters, squatting, “guerilla theater/art,” etc. — with varying speeds of the “art of looking” were everyday life.

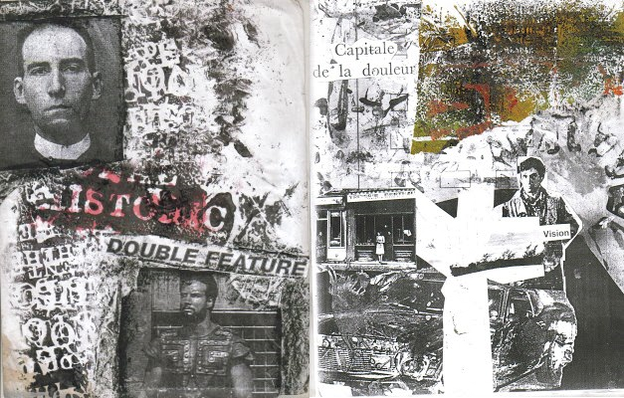

The “everyday life” of the streets learned then became my choice of studio. Almost all my rubbings and clay impressions pieces are made directly from things found in the streets which bear the marks of their everyday existence there. The evidences of time in the existence of the objects and their being encountered in the time of the artist create the pieces’ mixing of fragments, distortions, cracks, textures, sonic and visual effects.

For a six-year period in the 1980s, my interest in speeds of movement and seeing in the city was part of what led to my addiction to speed — amphetamines of all sorts. When I first was addicted, I was writing regular and freelance film and music reviews, interviews, and essays for various papers in Boston. I also worked a couple jobs and had a busy private life. Speed has a very peculiar effect on creating. At first it’s a stimulus to work, but then it takes a strange turn. The speed at which one is perceiving and thinking makes for a widening gap in the transfer of these to expression.

Everything one sees becomes so filled with possibilities moving at such high speeds that one loses the ability to hold on to them long enough to “record” them. Creative arrangement of elements turns into the obsessive collecting of elements that less and less often are used to make anything. When the gap with expression becomes too great, creative expression stops and is replaced by a sense of one’s own mechanization.

This results in the paring down of existence to the automatic physical movements, such as work and dromomania, with its endless finding of more talismanic and unused materials. The “art of looking” begins to experience gaps and distortions within it. Hallucinations, paranoias, senses of conspiracies, and a greater and greater interest in the synchronicities of events and signs take over. A “magical thinking” predominates and the energy to create becomes devoted to an obsession with interpretation.

The speed created ever-increasing deprivations physically and creatively. I stopped reading and writing and became immersed in the signs in the street. They had no meanings in language at all — but sent signals at the edges of understanding. These strange signals all but erased writing and replaced it with wordless signs. The distance between oneself and others grows eerily.

In one of the only good articles I have ever read about speed and its effects, the interviewer asks a long-time addict how he would show an addict if he painted a picture of one. “I would show him as looking,” the addict says, ‘but at what it is hard to say.’”

The positive effect of all this was it kept the “art of looking” alive, even if very strangely, and the dromomania led to encountering many new people. Since most of them were “street punks” and runaways, it presented a new world of signs to become involved with that was creating things — artwork, zines, music, events. The DIY aspect of punk, and now hardcore, made complete sense. The only thing in the way was the addiction to speed.

Williams S. Burroughs points out over and over that no creative activity took place during his addiction to heroin. It is only the turning away from this that gives release to an immense reserve of collected experiences, lookings, soundings, signs, and their interrelationships with the streets and action. When I got off speed was when I first began daily work on collages, little handmade books, and zines. That was the first time in my life that creative work became the everyday core of being for me. I found I could make use of all I had seen and found and lived in those last six years. And now the “art of looking” developed methods of expression of my own. Due to life circumstances changing, this went underground again for about ten years.

Since 1996–97, I have been involved in mail art and visual poetry, sound scores, event scores, essays, poetry, and prose poetry. As Geof mentions, for me the biggest event in this period of my life was meeting Bob Cobbing. This changed the direction of my life in too many ways to discuss here. Seeing his work and meeting him was a shock of recognition. It was the first encounter I ever had with someone whose ways of seeing and hearing were so like what I lived with and had come to think of as being as an aberration limited to myself alone. After meeting him, I never felt alone again in these; he made me aware that if I worked the rest of my life there was a possibility of expressing these things in a way others may understand. That way, one hopes to be able share the methods and findings of an “art of looking” that may be of interest and use to them in working on theirs.

So many major events in life and work have happened in the last years — some of the very best and some of the very worst and most brutal. The most important is that no matter the circumstances and conditions, one keeps finding ways to be working and developing an “art of looking” and expressing this.

“Childhood recovered” with the lessons of finding discarded things in the world to create with taught one early the links between the art of survival and the art of looking.

“Necessity is the motherfucker of invention” means there is always something hidden in plain sight with which to work and survive and work some more. There’s no need to “run away,” to “live and fight another day.” All you need is right there in front of you. And from there myriad new worlds begin to open all around one … hidden in sight, no end in sight … there for you to find.

[addendum, from a letter 30.xi.17. This is an essay I thought might be of interest re. “Outsider Poetry/Art” and its interrelationship with an “Outsider Life”:]

A number of times, presenting my visual works and performance event scores to some galleries, I was told they did not present “Outsider Art.”

Like many persons considered by society as an “Outsider” due to the facts of one’s life, or the sense on some persons’ part that one does not “fit in” — like many such persons (addicts, prisoners, those living well below the poverty line, etc.) or — as we say in Narcotics Anonymous and AA — those whose lives are leading to “jails, institutions and death,” a great many such persons find themselves being “saved” by finding their creativity in making art and writing and performing poetry, and by these means finding a way to “connect” to society in a recognizable way. I know in my case this is very true.

My great friend, the visual poet and essayist Petra Backonja, wrote me that she became immediately interested in my work on first seeing it, saying it stood out above anything seen in various visual poetry exhibits, anthologies, journals, websites, etc. — because “it looked like the artist’s work was a matter of life and death.”

I think that these are all some elements of “Outsider” works — far Outside as the Outsider feels, thinks, exists — there is not only the struggle of literal “life and death” — but also that of a struggle of the “life and death” of the imagination.

[For further exam of David-Baptiste Chirot’s visual art and poetry, see his flickr.]

Poems and poetics