Peter Valente: Fragmentary Improvisations of Yearning

küçük İskender's 'souljam'

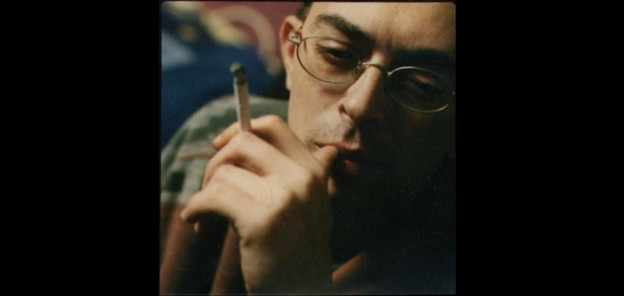

[introduction. About a year ago I began discussions with Murat Nemet-Nejat on the subject of contemporary Turkish poetry. From these discussions was born a series of notes, experimental essays, and brief commentaries. The following text is based on a reading of küçük İskender’s souljam (see photo, above), in Murat’s translation, included in Eda: An Anthology of Contemporary Turkish Poetry published by Talisman House in 2004. k. İskender (1964– ) belongs to the group of Turkish poets, that if alive in their fifties, would also include Lale Müldür, Ahmet Güntan, Seyhan Erözçelik, Sami Baydar, and Haydar Ergülen; this poetry is a reaction to the changes in Istanbul’s population and the city’s central political and cultural position in the world after the fall of the Soviet Union. Istanbul had become a “nexus of movement, a sprawling, global metropolis”; it was no longer a city of one million people, of secrets and mysterious depths. In souljam, İskender tears apart the official facade of Turkish culture with “a big bang from the center of the soul.” His language includes references to pop culture, the sciences, and crime reports; but there are also lyrical outbursts and archaic language. This complex hybrid reflected the new Istanbul of exponential growth and development. İskender created souljam from the contents of twenty notebooks, journals he kept from February 19, 1984 to December 26, 1993. The poem reverses the order of the notebooks; the lowest-numbered fragment corresponds to the latest notebook. This is İskender’s attempt “to suppress the chronological confusion, to push it to the very beginning, to a faetal sensibility.”

In my text, I allude to İskender’s radical view of Sufism. In Sufism, the ego must break down in order for the soul to begin its ascent toward God. According to İskender the physical body breaks down in a kind of orgasmic rapture, but the ego does not die. It becomes divine. I also refer to the Sufi concept of the arc of descent and ascent, which is the movement from the multiplicity of phenomena to the unity of God and the reverse. This movement is not sequential but continuous, two aspects of the same divine essence. In souljam this multiplicity is expressed in the form of fragments, imploding, exploding and transforming themselves in relation to another, yearning for unity with God through the body. My “essay” is an improvisation on the text, a record of my encounter with the fragmentary and volatile quality of souljam, rather than a conventional essay. The quotes from souljam are in italics. (P.V.)]

wounded electricity complements the body NOT Whitman’s Body-Electric but the fragmented body (Artaud’s “body without organs”) and there is also perhaps the suggestion of electroshock, the shockwaves of an explosive subjectivity. chimeras ghost whispering. Artaud’s vile spirits that inhabit the body as it exits the womb boy pulled into the four winds a cock in his mouth Body raped, abused, the brutality of life BUT (the poet) the bandit grows The poet will learn to curse, blaspheme (the dream in which I saw my grandma / burn her koran, I interpret it as / my sexual freedom), tear the sentences apart with his teeth, he is an enraged animal, sexually charged (I carry a zoo in me) 1) virus: valid declared — validates the main stream the criterion of language, all that is correct, the domination of truth, everything used to suppress the mind. What is valid is accepted, what is not is thrown into the garbage dump. And there are these geriatric gas positions itself in a suitable lung these stations in society areold, withered, of no use any longer. İskender rejects “the tradition” the suitable lung the right word; it is an attack on the sterility of language that maintains the tradition, this consensus in the aesthetic field and the owner of the building owns the words (Spicer’s “there are bosses in poetry.”) 2) the mystery: the weeping. mother earth, mother Istanbul, infected, shoots up and metal is happy industry, politics, institutionalism, the whole industrial revolution is shit and bomb happy (infiltration of communication by mechanical insulation) and condom is an insult tries to restrict pleasure to hold the sperm hostage and then night begins the rhesus monkey having turned human on an impulse (here is his origin story; and the brain’s awesome harmony is a giant tumor / of knee jerk reactions a primal fire that is cross-examined by a bureaucracy, (Burroughs’s “thought police”) but instead, violence, at bottom / is a crack of yearning. But the great white crosses and joins the captains log the threat, the abyss represented by Melville’s great white is domesticated, becomes part of language, conscripted for its use, becomes a tv commercial, part of the main stream, so the seagull panics does not want its sound reduced to a grammatical rule, eats up the weak worm of ionized penance here is an attack on Christian guilt, no need to confess anything. reconnection prowls around defensive techniques contra slow time (the organization of the journal entries defies a logical order, defies linear time. The “speed” of the poem is 100 miles/hr in a 20 mile zone) your face the desert shower of necessary love (In the phrase, “desert shower” contraries fuse, the dry desert gushes water) subject to rough trade (both rough trade agreements and rough sex), to deposits of excess dnas / long held in the mirage air. even the air is fake and the Dynamic Authentication System retrieves information about user’s hardware and software for authentication purposes. And your love is being recorded. Fatal/Foetal (the ultimate fatality is “death” (fast forward) but foetal suggests birth/origin, a reversal. Oblivion in both directions the path of my angels will track / through the blind / alley So we have here the continuum (“no tangible instant”). No difference between future or past. The poem races forward as fast as it races backward and at the same time, a railroad of sound And ‘and’ your suggests any possible union is cut off, fragmented like the sentence, like the lines of these pseudo poems, a fragmented body yearning for unity. crowds are inclinations of the like here is main stream, the tv sensibility, stream lined behaviors, the mob rules. my bequeathal / to the future as a strain of light a viral strain of light. İskender is a scientist in god forsaken solitude in the genesis of light / awaiting the lure of transparent insanity he is anteing up my concentration. İskender’s ego is in overdrive, he will beat God at his own game by determining the hour of his death rather than leaving it to accident or natural causes (my suicide is provided for) my mind / sores (soars) on a skin / white as cream// by cock’s / havoc / violated / in a hammock// Dream / and mid scream / and mid scream His bruise from being violated sexually is sublimated and becomes his means of flight (Murat Nemet-Nejat writes, “that violence (in spirituality and love) is the heart of Sufi sensibility and violence is sublimated as a cosmic principle.” This sore is also the viral strain of light. in solitude, me, full of hard ons ons ons here he arrives at the continuum through a physical sensation, in solitude. Here is an Artaudian resonance: that someone’s trying to kill me / is inlaying my mind, as if we’d / swapped secrets / making a night of it many, many nights / of drowse and bruise (again the sore and the dream, rough sex and sleep) how many whispered words mopped up by my fingers wandering on your lips, words I couldn’t catch words are cut off, inarticulate. The attempt to feel the other falls short. The subjectivity in İskender is extreme, contact with the world and the other is rejected. But this explosive subjectivity will be at the center of a radical Sufi practice where İskender yearns for the infinite contours of his consciousness. a kid defines night / as an etude of comprehending life / with his tiny cock, // like color blindness in smell blindness / experiencing carnation as a rose, / and me, experiencing carnation in a rose. The young boy’s experience of his own sexuality allows him to see day and night as one. Rather than the blind leading the blind with “accurate” and “valid” interpretations (translations) of, say the word, ‘carnation,’ which is interpreted as a rose, İskender purposely misreads the meaning of the word, (me, experiencing carnation in a rose.) and perhaps recalls that the meaning of the word ‘carnation,’ is derived from a misreading of the Arabic “Karnful” i.e. “clove as pink clove.” This is an act of creative translation and an attempt to go past the official meanings of words and perceptions that sustain the status quo (i a bit too out of line) But there is this sadness above me, / when will it stop brooding? the serenity and inner peace of not learning / one single prayer which I can recite by heart / dying God is out of the picture. İskender will control when he dies. His process is one of unlearning all the knowledge handed down to him and he will search out a love considered reprehensible by the planet earth by scanning the irradiation of my puckered fire and reading the shredded documents / of a long forgotten cult (this is his “Shamanistic, intuitive synthesis”) And furthermore he writes, useless! / god is useless. / i’m god. This heresy is also part of İskender’s Godless Sufism. It is the love, of a not yet visible asia, is / the barely sensible skin of plants. His love of what is not visible is like the barely sensible skin of plants. The invisible is felt. Here once again is the fascinating quality of these poems where a spiritual perception is arrived at by the physical. İskender’s identity is the befouling of what is / knowable, and the downward velocity / of becoming young he is atavistic, regressive, descending into the core of the earth, and back towards the origin, where he is young again; he has achieved a childlike innocence that is Blakean. (in our room of toys, / dreams are shaking off / anxiously their dust). İskender writes that linear logic is the use of perception’s least / common denominator. When he writes, the vitality of / science and discovery illuminated / in pure orgasm / only he seems very close to the Rimbaud of the Illuminations. He wants to negate the deviation / inherent in the deficiencies and deflations of choosing among / food or lovers the limitation of choice; he rejects convention, says “no both.” He speaks of the pure orgasm that is the extreme pleasure point (spiritual) of his radical subjectivity. The instability of knowledge and knowing: the difference between knowing that what is merely visible is woven / into what is longed for, and spelling out / that what is merely accepted is in conflict with what is rumored / about. over extending, / over exploring of myself. away from faith but very near / dissolution, a sentence, whose subject / is neurosis, whose sentence is dying, whose teleology, / mist Here is the Godless form of Sufism, the rejection of faith. but very near dissolution: Here is İskender’s radical subjectivity in which the breakdown occurs, a destruction not of the ego but of the world in seeking a primal unity. The structure of the sentence is breaking apart. Attempts to explain phenomena fail because they are as vague and inconsequential as the mist. Then there is the reality sandwich or Burroughs’s naked lunch on the end of a spoon, reality check: charred bodies in between the sheets, in a grimy all night hotel, inhaling the smoke from a crack joint (ecstatic drug use, expansion of consciousness, his blur of moans) i’m it: the ego does not break down. He is the world. But İskender writes my soul the bribe given my body This reminds me of Artaud, the soul as something immaterial that invades the body, and constantly instills in it a sense of lack. The body against its will becomes indebted to the soul. And it is this very immaterial quality, this “misty” quality that makes it so hard to attack directly and requires nothing less than the destruction of the World. Life is another form of immaterial invasion that does not care for humans and continues on irrespective of human achievement (this is Bronk’s territory). But İskender writes life probed me. my heart lets go. “gotch ya!” my heart won’t notice. He will ignore Life. Here is İskender’s radical subjectivity again. He rejects any talk of Being and the World. Rather, death is the ultimate mother fucker i cherish vamping poems. Nothing is original, there are no masterpieces; the ultimate and only challenge for the poet is Death. İskender wouldn’t have it any other way. the divine body like a broken sculpture and violence is the foreign tongue of the body: this also reminds me of Artaud. İskender is doing violence to his text, rearranging the initial order of his journals, breaking syntax, creating an undercurrent of destruction, the fragmented body/text is a roar, an almost hysterical rejection of everything that constitutes society, and his is a radical ego whose fragmentary improvisations of yearning are his ladder up down the arc. There is also the radical melancholy of Sufism: spring wrote me no letters of utopias, winter did. İskender is against nature, growth, the lure of Spring, and instead finds his own subjective vision of utopia in the cold, winter season, the season of snows, of death: death is the ultimate mother fucker. But his “suicide” is provided for. He is without a womb, self-generated, ego driven, a “body without organs”. The body is not his own. It’s for rent. You don’t sell your body, only rent it. And at what price? And since a body / without a soul / is called a corpse, no difference between entering any old whore house & fuck someone there & fucking any old corpse … obsessions of necrophilia both.” But then he writes, “except for my own life, except for my own life.” i.e. the ego still lives triumphs over death.

Poems and poetics