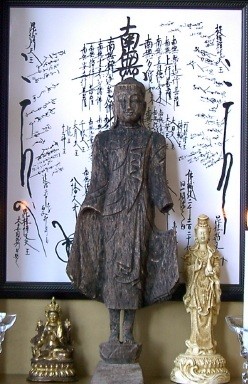

Outsider poems, a mini-anthology in progress (42): From 'Theragāthā' and 'Therīgāthā' (Pali, 1st century B.C.)

Translations by Andrew Schelling & Anne Waldman

[EDITOR'S NOTE. The following – all but the commentary – comes from selections & translations assembled by Schelling & Waldman that give a sometimes startling view of the poetry created by the early Buddhist outsiders/outriders whose homelessness & wanderings might later serve as a template for the uses of a poetry outside of poetry as such. The link here between experience & poetic form is a marker of outsider poetry as we’ve come to know it in our quest for a vehicle, a book, to bring it all together. (J.R.)]

MAHAKALA SPEAKS

This lady who cremates the dead

black as a crow –

she takes an old corpse and breaks off a thighbone,

takes an old corpse and breaks off a forearm,

cracks an old skull and sets it out

like a bowl of milk

for me to look at

Witless brain don’t you get it –

whatever you do just

ends up here

Get finished with karma, finished with rebirth –

no more bones of mine

on the slag heap

KASSAPA THE GREAT

I came down from my

mountain hut

into the streets one day

to beg food

I stopped where a leper

was feeding himself

With his rotted leper’s hand

into my bowl

he threw a scrap

into my bowl as he

threw it

one of his fingers broke and also fell

I simply leaned against a wall

and ate

Taking whatever scraps

are tossed

finding medicine

in cow dung

sleeping

beneath a tree and wrapped in

tattered robes –

only a man like that

walks free in all the four

directions

only a man like that

walks free

UPPALAVANNA

Uppalavanna was stunning. She had skin the color of the heart of the blue lotus.

“Give us your daughter,” everyone begged of her father. But Uppalavanna

rencounced the world. She repeated the verses she’d heard:

My daughter

and I

married the same man!

O horror

it’s unnatural

My hair stands on end

Sensual desire is

a thick

and thorny jungle

She is visited and challenged by Mara [Death] in a sal-tree grove.

Mara:

Such beauty is

vulnerable in

this fragrant grove

Foolish girl –

aren’t you afraid of

being raped?

Uppalavanna:

Were there

a thousand rapists

No hair of mine

would stiffen or tremble

What can you do to me?

I’ve got the same magic you do, Mara

I can disappear into your body

Look!

I’m standing

between your eyebrows

and you can’t see me

COMMENTARY

by Jerome Rothenberg & John Bloomberg-Rissman

SOURCE: Andrew Schelling & Anne Waldman, Songs of the Sons & Daughters of Buddha, Shambhala Publications Inc., 1996.

Out of my mind / deranged with love of my lost son / Out of my senses / Naked

– hair disheveled / I wandered here, there / I lived on rubbish heaps / in a cemetery,

on a highway / I wandered three years in hunger and thirst / Then I saw the

Buddha / gone to Mithila / I paid homage / He pitied me / and taught me the

Dharma / I went forth into the homeless state (spoken by Vasitthi)

It’s the deliberate outsiderness, then, that marks them, a move into the margins, mirrored across millennia & continents by self-elected saints & poets. For those whose songs were later written down, the goal was a shared homelessness or else a refuge in the old/new wilderness, “to live as wanderers and seekers … in caves or woodland huts.” With that came – as it would for others, elsewhere – a turning to the common language, Pali in the present instance as a deliberately constructed counter to hieratic Sanskrit, & with that a new poetics as the sign of a new life.

Since their first gathering, the poems have been divided into two segments or books – the Theragāthā as songs (gāthā) of the early male followers of Buddha & the Therīgāthā as those of his early female followers. To the songs themselves, arranged from shortest to longest, the ancient anthologizers added short prose narratives, written with an earthiness & matter-of-factness much like that of the songs they put in context. What comes across, with little interference, is a mixture of hope & terror / terror & hope, that we might take for ourselves as the mark of all great poetry. The terror, then, in the following:

I tell you the world is blazing, blazing

the whole world’s in flames

I tell you it’s flared up

the world is shaken

your worlds are shaken

the whole world’s ablaze.

& the hope & sense of liberation:

O King, I have attained the goal

for which I went into the homeless state –

I have annihilated the fetters.

The odds have never been easy.

Poems and poetics