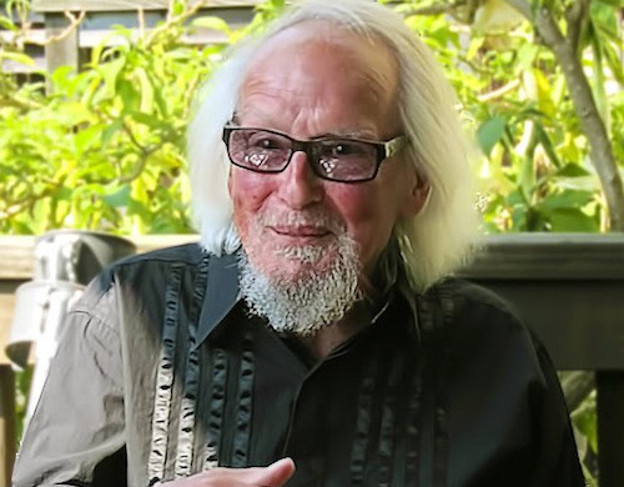

Jerome Rothenberg: On the achievement of David Meltzer, a preface & a memorial

[The word of David Meltzer’s death came to us the morning after & on the threshold of a new & dangerous year in which his friendship & kindly spirit will be greatly missed by the many of us who drew from & treasured his grace of mind & the life of poetry that surrounds it. In the immediate aftermath I thought to reprint the preface I was privileged to write for his selected poems (David’s Copy, Penguin Poets, 2005) & the short poem, composed by gematria, that follows. There is much more to say, of course, and I hope still to say it. (J.R.)]

TENS, FOR DAVID MELTZER

(A Gematria Poem)

Ten riches.

Ten fountains.

Ten wrestlings.

Ten cities.

Ten wonders.

Ten hairs.

Ten

& ten.

A PREFACE

(for David’s Copy, 2005)

I first became aware of David Meltzer — as many of us did — with the publication in 1960 of Donald Allen’s anthology, The New American Poetry, that celebrated the emergence over the previous decade of a new & radical generation of American poets. Those included ranged in age from Charles Olson, already fifty, to David Meltzer, then in his early twenties. Meltzer’s four poems were all short, filling up most of three pages, & displayed a surefooted use of the kind of demotic language & pop referentiality that was cooking up in poetry as much as it was in painting. His lead-off poem mixed traditional Japanese references with more contemporary ones to Kirin Beer & Havatampa cigars, but there was otherwise no indication of a wider or deeper field of reference — as in the work, say, of older contemporaries such as Olson & Robert Duncan, or of Ezra Pound or William Carlos Williams or Louis Zukofsky before them. Like many of our generation, his aim was not to appear too literary; as in the conclusion of his biographical note: “I have decided to work my way thru poetry & find my voice & the stance I must take in order to continue my journey. Poetry is NOT my life. It is an essential PART of my life.”

It took another decade of journeying for Meltzer to emerge as a poet with a “special view” & with a hoard of sources & resources that he would mine tenaciously & would transform into unique poetic configurations. For me the sense of him had changed & deepened some years before I got to know him as a friend & fellow traveler. The realization — as happens with poets — came to me through the books that he was writing & publishing & that I was getting to read — on the run, so to speak, like so many others. In The Dark Continent, a gathering of poems from 1967, I found him moving in a direction that few had moved in — or that few had moved in as he did. The “transformation,” as I thought of it, appeared about a quarter of the way into the book — a subset of poems called The Golem Wheel, in which the idiom & setting remained beautifully vernacular but the frame of reference opened, authoratatively I thought, into new or untried worlds.

The most striking of those worlds was that of Jewish lore & mysticism, starting with the Prague-based legend of Rabbi Judah Loew & his Frankensteinian creation (the “golem” as such), incorporating a panoply of specific Hebrew words & names along with kabbalistic & talmudic references & their counterparts in a variety of popular contexts (Frankenstein, The Mummy, Harry Bauer in the 1930s Golem movie, language here & there from comic strips, etc.). It was clear too that the Judaizing here — to call it that — was something that went well beyond any kind of ethnic nostalgia, that he was tapping in fact into an ancient & sometimes occulted stream of poetry, while moving backward & forward between “then” & “now.” In an accompanying subset, Chthonic Fragments, a part of it presented in the present volume, he expanded his view into gnostic, apocryphal Christian, & pagan areas that left their mark, as a kind of catalyst, even when he swung back to the mundane 1960s world: the “dark continent” of wars & riots, the funky sounds of blues & rock & roll, the domestic pull of family & home.

I mention this as a recollection of my own very personal coming to Meltzer & to the recognition that he was, like any major artist, building a special world: a meltzer-universe in this case that spoke to some of us in terms of our own works & aspirations. (“The Jew in me is the ghost of me,” began one stanza in The Golem Wheel, & I was smitten.) His pursuit of origins of all sorts was otherwise relentless — not only in his poems but with a magazine & a press that also took as their point of departure or entry the hidden worlds of Jewish kabbalists & mystics. The magazine was called Tree (etz hayyim, the tree of life, in Hebrew) & was connected as well to a series of anthologies of his devising (Birth; Death; The Secret Garden: An Anthology of the Kabbalah), alongside chronicles of jazz writing & jazz reading & of poetry — Beat & other — that had emerged or was emerging from the place in California where he lived & worked.

What was extraordinary here was the lighthearted seriousness of the project — a freewheeling scholarship in the service of poetry — & his ability to cast an esoteric content in a non-academic format & language. In this he shared ideas & influences with a range of contemporary artists & poets — notably the great West Coast collagist Wallace Berman, whose appropriations of the Hebrew alphabet as magic signs & symbols led directly to what Meltzer, borrowing a phrase from Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, called Bop Kabbalah. It was also in that California ambience that he made contact with older poets like Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, & Kenneth Rexroth, & with younger ones like Jack Hirschman, engaged like him in the search for old & new beginnings. In circumstances where everything suddenly seemed possible, he joined with his wife Tina (as singer) & with fellow poet Clark Coolidge (as drummer) to form a rock performance group called Serpent Power — the name itself an echo of ancient yogic & tantric practice.

The totality of Meltzer’s work will wait for another occasion — a Meltzer Reader perhaps or a collected Meltzer — in which all of it can be mirrored. For now – & not for the first time — he has condensed his nearly half-century of poetry into the pages of this book. As such it is a reflection of where he has worked & lived, often with great intensity — first in polyglot New York (Brooklyn, to be exact) & later (most of his life, in fact) in California. He has never been a great traveler, in the literal sense, but his mind has traveled, metaphorically, into multiple worlds. In the process he has drawn from a multiplicity of times & places & set them against his own immediate experience. His attitude is that of a born collagist, a poet with a taste for “pilfering,” he tells us, or, paraphrasing Robert Duncan: “Poets are like magpies: they grab at anything bright, and they take it back to their nest, and they’ll use it sooner or later.” And he adds, speaking for himself: “I use everything, everything that shone for me.”

The range of the work itself follows from another dictum: “Poems come from everywhere.” As such, the focus moves from the quotidian, the everyday, to the historical &, where it fits, the transcendental. The mundane stands out, for example, in a poem like “It’s Simple,” though not without its underlying “mystery.” Thus, in its opening stanza:

It’s simple.

One morning

Wake up ready

For new work.

Pet the dog,

Dog’s not there.

Rise & shine

Sun’s not there.

Take a deep breath.

No air.

If the presentation here gives the appearance of simplicity — something like what Meltzer calls “the casual poem” — we can also remember his warning, that “art clarifies, it doesn’t simplify,” that his intent as a poet is, further, “to write of mysteries in language as translucent and inviting as a mirror.”

Mystery or “the potential of mystery” is a term that turns up often in Meltzer’s poetics — his talking about the poetry he & others make. It is no less so where the poem is family chronicle than where it draws on ancient myth or lore: the fearful presence in “The Golem Wheel”

… returning home to a hovel

to find table & a chair

wrecked by the Golem’s fist

or the celebration & lamenting of the parents in “The Eyes, the Blood”:

my father was a clown,

my mother a harpist …

There is a twofold process in much of what he does here: a demythologizing & a remythologizing, to use his words for it. In this sense what is imagined or fabulous is brought into the mundane present, while what is mundane is shown to possess that portion of the marvelous that many of us have been seeking from Blake’s time to our own.

David’s Copy is full of such wonders, many of them excerpts from longer works that show a kind of epic disposition — in the sense at least of the long poem as a gathering of fragments/segments/image-&-data-clusters. Watch him at work, full blast, in the two excerpts from Chthonic Fragments or in the“Hero” & “Lil” excerpts from what was originally his long poem, “Hero/Lil,” in which he draws the Lil of the poem (= Lilith, Adam’s first wife; later: the mother of demon babes) into the depths of post-exilic life:

She-demon deity

lies on the sofa

stretching like a cat.

Small hot breasts.

Miles breathes Blackbird.

She accepts

the hash and grass joint.

Cool fingers

Dive under my pants

ka! ka! ka!

Screech of all

Lil’s hungry babies

caged-up next door.

Or again:

She wants words only at dawn.

I touch her mouth with language

then afterwards move against her.

In other serial works the touch is lighter, where he observes or playfully takes the role — totem-like — of magical yet ordinary animal beings: the dog in Bark: A Polemic, say:

Bark is what us dogs do here in Dogtown

also shit on sidewalks door mats proches trails

wherever new shoes walk fearless.

Bark is what us dogs do here in Dogtown

it’s a dog’s life

we can’t live without you.

Mirror you we are you.

Beneath your foot or on the garage roof.

You teach us speech bark bark

for biscuits we dance for you.

You push us thru hoops

& see our eyes as your eyes

but you got the guns the gas the poison

all of it.

Bark is what us dogs do here in Dogtown.

Or the Monkey in the singular poem of that name — both pseudo-orthodox (“bruised before Yahweh”) & quasi-stylish (“suave in my tux”).

These are the marks of a poet who has worked over a span of time, to pursue interests near & dear to him. To cite another instance, music — the full range of it for Meltzer — comes into a large portion of the poems, a reflection of his own musical strivings inherited in part from his harpist mother & cellist father, celebrated in the long poem or poem series, Harps, itself a section from a much longer ongoing work called Asaph, one intention of which is to use music, he tells us, “as a form of autobiography.” Of such musically engaged works the great example is his recent booklength poem for Lester Young, No Eyes, from which he has generously selected for the present volume. Add to that another big work, Bolero (also a part of Asaph), & short poems or references to Hank Williams (the “lamentation” for him), Billie Holiday (“Darn that Dream”), & Thelonious Monk, among recurrent others. Later too, when he becomes a chronicler (Beat Thing the most recent & most telling example), the music of the time, like its poetry & loads of pop debris & rubble, has a place at center.

I would cite Beat Thing in particular as both his newest book as of this writing & as something more & special: a harbinger perhaps of things to come. As recollection & politics, it is Meltzer’s truly epic poem — an engagement with once-recent history (the 1950s) & his own participatory & witnessing presence. If the title at first suggests a nostalgic romp through a 1950s-style “beat scene,” it doesn’t take long before mid-twentieth-century America’s urban pastoralism comes apart in all its phases & merges with the final solutions of death camps & death bombs from the preceding decade. This is collage raised to a higher power — a tough-grained & meticulously detailed poetry — “without check with original energy,” as Whitman wrote — & very much what’s needed now.

The reader of David’s Copy will find in the more recent poems that end it a sense of timeliness amidst the timelessness that poetry is often said to offer — Beat Thing clearly but also Feds v Reds, Tech, or even Shema 2 with its linking of Judaic supplications & Koranic language in the wake, I would imagine, of the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The political engagement — embedded in the poetry itself — is both real & heedful of his earlier remarks that looked down at the “onedimensionalizing” of so much political poetry (“a tendency to supply people with conclusions, but you don’t give them process”) in contrast to which “a certain kind of pornography was what I wanted to do as politics.” And that in fact was something that he also did — a genre of novel-writing that he called “agit-smut” and described as “a way for me to vent my rage and politicize … a way of talking about power.”

Elsewhere, in speaking about himself, he tells us that when he was very young, he wanted to write a long poem called The History of Everything. It was an ambition shared, maybe unknowingly, with a number of other young poets — the sense of what Clayton Eshleman called “a poetry that attempts to become responsible for all the poet knows about himself and his world.” Then as now it ran into a contrary directive: to think small or to write in ignorance of what had come before or in deference to critic-masters who were themselves, most often, non-practitioners & non-seekers. By contrast, as is evident throughout this book, Meltzer allied himself with those poets of his time & place (Beats & San Francisco Renaissance & others) who were both international in their range & the true carriers or creators of traditions new & old.

It was at this juncture that I met him, & his companionship added immeasurably to my own work as a poet. I continue not only to prize him but to read his poems with the greatest pleasure.

Poems and poetics