From 'Eye of Witness' (3): The poem as an act of witness

[It was with Heriberto Yépez, first in Ojo del Testimonio (2008) and now, in the process of coediting Eye of Witness: A Jerome Rothenberg Reader, that I found myself digging into earlier work to come to terms with the idea of witnessing as a basis and prod for my own poetics. With that in mind I have come to a slow understanding of how that idea, still in process, has been central both to my poetics and to that of various others, known and unknown to me. The following are some short excerpts from Eye of Witness, but the body of my work in different genres seems permeated by the concept, and I find myself more willing than ever to stand behind it. While I know that others would come at it quite differently, I read it now as a common thread for all we hope to know. That “all,” I wrote some years ago, includes the world, the present, as it comes and goes. I am a witness to it like everyone else, and all the experiments for me … are steps toward the recovery/discovery of a language for that witnessing. It can never be more clear than that, nor should it. (J.R.)]

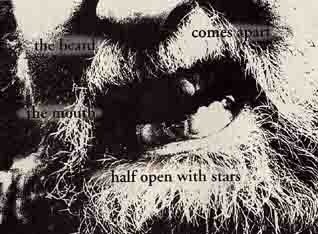

From Prologomena to a Poetics, for Michael McClure

……..

Our fingers fail us.

Then tear them off! the poet cries

not for the first time.

The dead are too often seen filling our streets,

who hasn't seen them?

A tremor across the lower body,

always the image of a horse's head

& sandflies.

A woman's breast & honey.

She in whose mouth the murderers stuffed gravel

who will no longer speak.

The poet is the only witness to that death,

writes every line

as though the only witness.

From “The Sibila Interview: The Poem as an Act of Witness”

Charles Bernstein. Many of the poems in A Book of Witness, your new book from New Directions, are centered on the possibilities of the "I", and by extension, personal expression. Yet much of your work, as editor, poet and translator, has worked to decenter conventionally self-expressive verse. Can you talk about the tension between expression and construction in your work?

That was certainly one of the driving ideas in A Book of Witness, something that I had had in mind before but on which I had never acted so deliberately. The question of self-expression had come to dominate many of the conventional approaches to poetry, to make poetry almost exclusively an arena for the lyric, first-person voice. Like most of us, I came out of that mind-set, and like many of us, I resisted it. My idea for poetry was that, even where we worked in shorter forms, the range of voice accessible to us, like the range of subject or vocabulary, should be unlimited. At the same time I was fascinated by certain works – largely but not exclusively ethnopoetic – in which the first person (“I” and “me”) was used in ways that went far beyond the personal. I gave a number of examples in Technicians of the Sacred and the other anthologies, but the one that I took as template came from the María Sabina veladas – wall-to-wall first person but every utterance attributed to a mythic other voice:

I am a little launch woman, says

I am a little shooting star woman, says

I am the Morning Star woman, says

I am the First Star woman, says

I am a woman who goes through the water, says

I am a woman who goes through the ocean, says

I am the great Woman of the Flowing Water, says

I am the sacred Woman of the Flowing Water, says

But even before I knew about María Sabina, I was using the first person in that way – maybe derived from African praise-poems, maybe on my own:

I am the man who held the keys.

I asked you to forgive me.

I was the first to be insistent and the last to leave.

I vomited.

I didn’t come there often.

I was eager and alive.

I was not the least among them.

Once I was.

Once I remember being in a poor position.

I applied for membership.

I was sad.

Then I thought no longer to go on living.

I turned from you and offered you my keys.

You turned beside me and offered your position.

I had turned against them.

All of that, as you point out, is a compositional as well as an expressive matter, and I’m not sure if expression or self-expression is anything but misleading when we talk about it. Looking back now, I see that in that last poem I was using the “I” pronoun to set up a series of repetitions, more for the sake of contradiction than agreement. I could switch of course to third person (“he” or “she” or “they”) with similar results, but the power of the “I” and a certain fluctuation in its use – between fact and fiction – had a different meaning. It was clear that language allowed the “I” to testify, but to what was it testifying and who in any instance was the person, the “I,” who was speaking? I began to feel, in that way, that an unfettered use of “I” wouldn’t so much lock in identity as put it into question.

Regarding composition or construction, there was another work which helped me to launch A Book of Witness and to which it has some necessary reference. I had been reading a little book by Jenny Holzer – Laments – and finding in it a still more complicated weaving of “I” utterances. For Holzer these seemed to function as narratives that formed a kind of postmodern version of Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology – twelve individuated “voices of the dead” she called them, but I read each one instead as a series of overlapping voices and identities. I also had a number of other things in mind – compositionally, I mean, as well as intellectually: that the utterances would be separate from each other as I wrote them and would form a unity only later, or however it fell out; that they would include brief “I” utterances from other poets, most of whom I would identify in the margins; and that they would constitute a long series (a hundred poems in total) where the reiteration of the form affected and changed the reading of the individual poems.

Cecilia Vicuña. In the pre-face to the New Selected Poems 1970-1985, you speak of yourself as a witness, as I understand it not just to the world, but to your own process, which leads us to the old question of "el desdoblaje", being in and out of yourself at the same time while performing. Would you care to explore this further?

This is a different question from Charles’s, although it touches on similar ground and on the word “witness,” which is, I suppose, central to my idea of what the aim of my poetry may be. In the pre-face you mention, the declaration about witnessing goes as follows: “I am a witness like everyone else to [the world, the present, as it comes and goes], and all the experiments [the poems] for me … are steps toward the recovery/discovery of a language for that witnessing.” At the same time I find myself shying away from such a claim, because it seems to me I’ve seen and felt so little. I keep coming back to it, however, with a sense that a little may be enough and that I can use the means at my disposal to be a conduit for others – at its most intense for others who have seen and felt a lot.

In Khurbn, the cycle of poems I wrote about the holocaust, I opened myself to other voices, witnesses to those events, by composing, constructing, texts – my own words interlaced (collaged) with theirs. A Book of Witness is much more constructed, much less constrained by its thematic. Here I take the first person (“I”) as voice of witness and follow wherever it leads me, while at the same time I confront the problematics of witnessing and the possible lie of speaking in the first person – in the witness’s voice. I am aware here too of the degradation of the first person, both by poets close to me who disparage it and by others who restrict it to a narrow, “confessional” perspective. In the Postface to A Book of Witness, I speak of it as “the instrument – in language – for all acts of witnessing, the key with which we open up to voices other than our own.”

When it comes to performance, however, I appear as who I am – as the presenter of my own works or of works like Hugo Ball’s Karawane or Schwitters’ London Onion that I’ve appropriated for myself. I’m not aware of acting a role other than myself; that is to say, I don’t have to get into character to perform, as an actor would, but have only to work myself into the performance as a musician might. In doing that I’m aware as well that “myself” in the act of performance feels different for me than “myself” does otherwise. I like your word desdoblaje, which I take as a splitting apart or a breaking in two, and I think that what I’ve said just now may be my version of it.

Or put more simply: I hear myself speak and in that moment of performance I am both subject and object: the one who listens and the one who speaks.

From A Book of Witness: “i-Songs Exist”

i-songs exist, (I. Christensen)

& I have sought them,

playing an empty hand.

i is your mother,

is a good day

& also not.

i equals nothing

in the game of numbers

where it is also ten

& jew.

i is a womb

a belly

something stolen

heart & hand.

i eats

& will be eaten.

i is a habitation.

i is go & good.

i is a power.

i is to God

a question.

i is willing.

i is i-am

but stands confused.

i is a name for ice.

i is an end.

Postscript to A Book of Witness

A Book of Witness was my passage from one century – one millennium – to another. The first fifty poems were written in 1999, the second fifty in the two years that followed. When I came into the street that first day in the year 2000, it was one of those bright California mornings, & I was struck, very forcefully, by the curious name of the year & by a feeling that I was entering another world. While I didn’t put much stock in that kind of era-shifting, my mind that morning still held an image from something I had seen on television the night before – a series of movie clips showing earlier twentieth-century views of what the coming century would be like. Millennium was a word I had been mulling over in that closing decade, most notably in the assemblage Poems for the Millennium that Pierre Joris & I put together & published in the later 1990s. The word itself, we knew, was slippery – associated as it was with a sense of apocalypse & destruction that often belied our rosier interpretations.

Witness was another word we held in common. In its twentieth-century usage it had a meaning – pathetic but real – that spoke to the horrors, great & small, that marked that time & that persist today. I had come to think of poetry, not always but at its most revealing, as an act of witnessing, even of prophecy – by the poet directly or with the poet as a conduit for others. I had also been struck by how crucial to all of that the voice was; I mean the voice in the grammatical sense, the “first person” centered in the pronoun “I.” I was aware, even so, of how that first person voice had either been debased or more frequently despised by many poets – often (where despised) by poets close to me. The intention, understandably enough, was to free the poem from its lyric shackles – “the lyrical interference of the individual as ego,” as Olson called it.

The loss of such expression, however, would be immense, & its elimination futile. For there are a number of ways in which that voice – first person – has been one of our great resources in poetry, something that turns up everywhere in our deepest past & present. I mean here a first person that isn’t restricted to the usual “confessional” attitude but is the instrument – in language – for all acts of witnessing, the key with which we open up to voices other than our own. I am thinking here of someone like the Mazatec shamaness María Sabina (& her echo in the work of our own Anne Waldman), who throws up a barrage of “I” assertions, when it’s really the voices of the gods, the “saint children” of her pantheon, whom she feels speaking through her.

There is in all of this a question of inventing & reinventing identity, of experimenting with the ways in which we can speak or write as “I.” In the course of putting that identity into question, I have brought in statements now & again by other poets – very lightly sometimes but as a further way of playing down the merely ego side of “I.” And I let the voices that I draw in shift & move around. I want to do that, to keep it in suspense. “I am I because my little dog knows me,” Gertrude Stein wrote in a poem she called “Identity.” I have written a hundred of these poems now – a century of poems -- & I hope that they’re both of this time & still connected to the oldest ways in which the poem makes itself.

Poems and poetics