Rodrigo Rojas

from 'Exercises on Infidelity,' two new poems in English, with a concluding 'footnote'

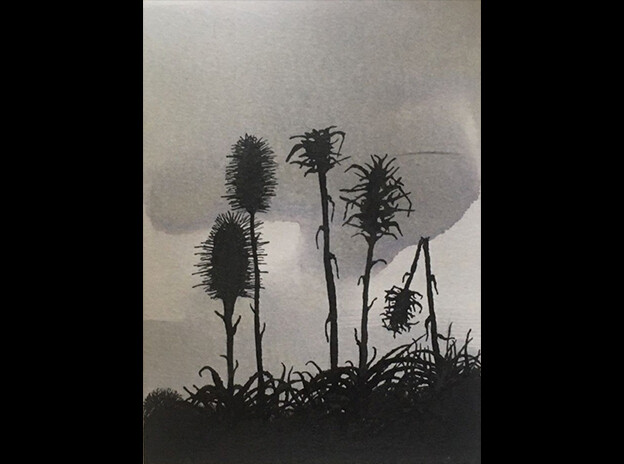

[Known as a poet-translator of contemporary Mapuche-language poets such as Elicura Chihuailaf, Leonel Lienlaf, and others, the Chilean Spanish-language poet Rodrigo Rojas has now made a further translingual shift into a series of poems written entirely in English. Of these he tells us: “These are not translations; the poems were written directly in English. The book is called Exercises on Infidelity because English is not my first language, but also because the idea of an original poem as the source of the poetic experience is questioned. The poetic experience here belongs to a space that is in-between, a place in which all expressive and perceptive limitations are enhanced and multiplied.” And of the Mapuche link: “I hold the Mapuche nation very close to my heart. I consider them to be my teachers and guides. I’ve studied their poetry and tried to understand the poetics they developed in order to speak to different worlds. One is their own culture in constant tension and the other is this hungry world (the first layer of it is the Nation State of Chile) that threatens their very survival.” Rojas’s English texts and well-wrought ink-and-brush drawings form the total content of this book.]

FINE, SOLUBLE & LIGHTFAST

It’s Indian

in English,

West Indian in Dutch,

but in German,

French

and Spanish

it’s Chinese ink.

Solid black

thick water dark

no gloss, but still

a journey.

I opened a 16 oz bottle, poured

some of the ink into a glass bowl,

dipped in a no8 flat brush

until it became heavy.

The night

is approaching. A brush

soaked in black

is necessary.

The hairs

must bend and slightly

spread over the white

of the paper. The outline

of the garden is first,

not the sky.

The proximity of night

means that darkness will rise

in between the plants.

It’s your everyday shadow

but swelling.

The brush

loaded will leave

a wide stroke

with some bubbles,

expanding the same way

shadows flood into each other:

a mass deep enough to rise

from the ground.

Thirteen minutes ago

the sun set, red

afterglows are dissolved.

This nectary blue

sky, uneven,

concave,

unlit,

is the source of all contrast.

Nothing falls through

that edge, the line

of night

closing in.

The flat brush allows

in one movement

to do the spines,

little teeth aligned

at the side of fleshy leaves.

Against the horizon

they could be a calf

of a sperm whale,

its lower jaw

out of the water

with its first

open vowel.

One brush stroke, one

Indian stroke

one Chinese solid

black ink.

The paper

and its tide

is oblivious to the weight

of the exotic

in its name.

But the brush dips

into all of that

as it paints on,

from wet soil

to the spiky tips.

Nightfall in roiled blue.

Darkness swelling

from the ground,

the unconfessed

imagination,

uncivilized

mirror subdued

in a 16 oz bottle

“made in the Netherlands.”

DROP EVERYTHING

Unpolished crescent moon. The light

is absorbed by the hammered silver

of her ceremonial jewels.

For the Mapuche the inward

radiance of mist is darkness drowning

as it gasps for light.

She comes in that luminescent

haze. I can hear her walking towards me

through the forest.

The wind has long slender

fingers stretching through

the trees. Flat leaves flap

like sheets on a clothesline,

the needles of conifers strive

to whistle but can only whisper.

In beauty, under this dark canopy

she walks. Patches of starry skies

in between the branches.

I hear the silver dangling

from her earlobes

before I can make out her face.

She asks for the glass, the first

urine at dawn. She searches

for inclusions

in a gemstone of thick

yellow resin, a crystal in the making,

the genuine insect in amber.

Everything now has a variable

translucent body, all that’s dark

has a concave light.

This is not happening, at least not

in the flesh. The healers called Machi

first reach out in dreams.

This Machi, Francisco tells me, is calling you.

He knows it, he’s a devoted Mapuche dream traveller.

As an artist he lets dreams do the curating of his shows.

He often dreams of messages for friends. I call him

to narrate my own dream and he says go, drop everything

and go. There is no other message, go to her.

Tonight a horse breathes out clouds that drizzle first,

then become lighter and rise as vapors

in the morning frost. The horse exhales to my face.

In this second dream the Machi speaks.

Take it all in, she says, expand, allow

the entire horse in your rib cage.

More fog as the horse neighs.

Its muscular neck turns to the side now.

I’m left alone in the dense cloud.

I hear the horse walk away as it nickers.

The glass in the Machi’s hands glints,

night dissipates.

I dial Francisco’s number again.

FOOTNOTE

I hardly write now; all I do is flip back pages in my notebook until I find the shadow of a poem. It can be a loose phrase with drawings or a dense block of notes. They begin invariably with:

What about a poem

where

Reading them is like eavesdropping into a chatty group you can’t see. It’s the cut-out voices of the people I might have been. But not just voices, flipping back I pass through whole weather systems, light drizzle here, sudden summer showers there, and in the next page constant winds so strong as to tilt life in one direction.

What about a poem

where a word like turba

is not just translated

into peat?

These entries are part of a speculative dictionary, a guide to speak in the troubled nation of myself. There is a light that shines from behind them, their shadows touch the tip of the page. As soon as that outline comes into view it dissipates. The note just captures that weightless shape as it dissolves, the paper fibers absorb a little ink and that’s it.

What about a poem

where the icy waters of the Beagle

recede and the rocks expose

their dark pubic kelp,

would Ryokan consider it

a zen poem?

As incomplete as they might be they also form a self-sufficient world that dies when plucked out.

[N.B. A related instance of Rojas’s translations into English of contemporary Mapuche poetry can be found here on Poems and Poetics.]

Poems and poetics