Chronicle: Interview with a Seneca songman, Richard Johnny John (Parts One & Two)

[What follows – my introductory note & Richard Johnny John’s account of his life as a traditional singer & songmaker – was originally published in Alcheringa, the journal of ethnopoetics that Dennis Tedlock and I co-published & co-edited in the early 1970s. Johnny John, whom I’ve celebrated elsewhere, was my adoptive Seneca father through the years I spent visiting & then living on the Allegany Seneca Reservation in upstate New York. Those years marked my opening to a world that would have otherwise been foreign to me – an adventure in poetry & life that has remained crucial to my sense of how poetry & life could intermingle. If that time & place are now far from me, they remain in mind & continue to inform my sense of poetry & what it may mean in my own life & in the lives of all with whom we share the few years afforded to us in our time on earth.

A full run of Alcheringa can be found at http://ethnopoetics.com/ and http://jacket2.org/reissues/alcheringa-archive-journal-ethnopoetics-1970.... (J.R.)]

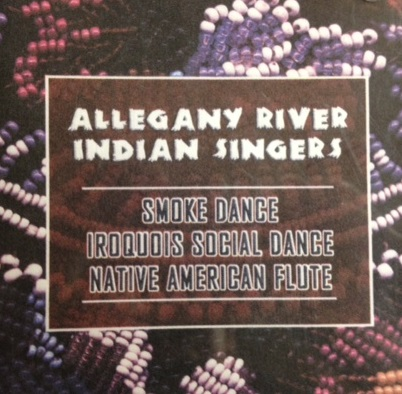

NOTE. Richard Johnny John was one of the leading singers & makers-of-songs at the Allegany (Seneca) Reservation in western New York State, descended from singers, some of them, like the two grandfathers he mentions, very important in their own time. The narrative is a piecing together of bits from a series of interviews between us in August 1968. I asked him to speak about his life as a songmaker (poet too in the use of both words & word-like sounds) & about the practice of his art as carried on within the heh-non-deh-not-ha or traditional Iroquois Singing Society.

The “woman's dance” songs mentioned throughout are the most popular of the secular or social dances, also the most interesting from my own point of view; i.e., they're the only ones still being made with any frequency & they often do have words to them, whereas most Seneca pop songs (& many sacred ones as well) are “wordless.” Typical structure of the contemporary woman's dance song is: intro sung by leader; repeat of intro plus 2nd part, by leader & chorus; repeat of whole by leader & chorus. Instruments are horn rattles for chorus, water-drum for lead singer. While I was at Allegany in 1968, the principal makers of woman's songs for the Cold Spring Longhouse Singing Society were Herbert Dowdey (then absent in Canada), Avery Jimerson & Richard Johnny John.

The Kinzua Dam is the flood control project on the Allegany River, backwater from which was supposed to sweep over that part of the reservation on which most of the Senecas were living. They put up a strong fight for an alternate plan, but lost & are now resettled on two sides of the proscribed land, still waiting for the waters to come in. The Gaiwiio (“code” or “good message”) was brought by the Four Beings to the Seneca prophet, Handsome Lake, in the last decade of the 18th Century, & resulted in a fundamental reformation of the native religion. Even so it retains many ancient features, both in the public ceremonies (or “doings”) at the longhouse, & in the rituals 0f the various medicine societies. It is today one of the principal vehicles for retaining a deeply-rooted Indian way-of-life among the Senecas.

My transcription of the interview follows.

***

1

How I really got started with songs was from the old-time Singing Society that they used to have amongst the oldtimers, amongst the older men. At that time there was a lot of older men that was in the Singing Society, and I kind of picked it off from them, the ways that they were singing. I guess everybody's got their own way of singing and how to make up songs.

There's quite a few old men that I remember. I can't forget my two grandfathers - they were both singers - and a lot of others besides. One of my grandfathers was Chauncey Johnny John naturally, and the other was Howard Jimerson. Then that goes all along through Amos Redeye (he used to do a lot of singing), Wesley White and Willy Stevens, Clarence White, Sherman Redeye: there was quite a few of them. And old John Jimerson used to do quite a bit of singing himself, made up a lot of songs. In years back too you can't forget Ed Currey.

All them oldtimers talked about even older men than they were, they called them oldtimers themselves, and there were still some older ones than they were. Even up till today we sometimes talk about the oldtimers, and we sing songs that's even older than what we are as of today. Sometimes we get in the mood to sing some of these oldtimers' songs, and they're really, I wouldn't be afraid to say that there may be some of the songs that we do sing today that are over a hundred years old; I wouldn't be afraid to bet that they are older than a hundred years old, some of them. Among the social dances too -like the old Moccasin Dance we have, that's a real oldtimer, I don't know how long back that has started up. Some of these dances and some of the songs that they do today have been danced from way back when the Caiwiyo first came to Handsome Lake. We used to have all of these different social dances, and some of the songs are still sung as we remember them.

In the old times, you know, when all these oldtimers used to get together, they'd pick out a spot, they'd go to somebody's house. In them days they didn't do like we do now: sometimes we go right to the longhouse and sing at the longhouse, have the singing group come to the longhouse; but in them days there was so many of them, that sometimes on both ends of the reservation there was singing. There'd be maybe a group down in Quaker Bridge, and then there would be another group singing in Cold Spring, all on the same night, there was that many of us singers in the old days.

Now we're so far apart and there's so few that really can sing, but in the olden days they would mostly go on foot to these houses, they were so close together. They all lived, I guess, in one big circle right around Cold Spring and Quaker Bridge; that was right in the middle of the reservation, and most of the longhouse believers were right in that circle. It was more or less handy for them to pick out a place where they could meet and sing on this one night, and then sometimes maybe if there wasn't any singing in Cold Spring, some of the Cold Spring people would come down to Quaker Bridge. The two groups would come together then: then you could really hear some good music.

They went to different houses too. They didn't have a certain night where they were going to sing, but anybody could say well, tonight we'll sing maybe at my place, and then maybe the followirlg night they'll say well, we'll go down to Quaker Bridge and visit some of our friends down there. This was a spur of the moment as I would say it. It wasn't like anything today. Today now, you're lucky if you can get three or four singers together, cause everybody else here is riding in cars, and there's so many things going on. Especially in the summertime: you can't get the singing group together in the summertime too much. It's more or less fall, winter and spring, I would say.

I've belonged to the Singing Society ever since I was 14 or 15 years old; that was in Cold Spring where we used to live. Old Lindsey Dowdey was our president at that time, and that's been a good many years ago, pretty close to, I wouldn't be afraid to say that was a good forty years ago when I first started to pay any attention to these singers.

I remember I used to sit over on the side. There was quite a few of us at that time that was about my age: some were a little younger and some just a few years older. They used to have us sit over on the side and listen to the older men sing. I guess we were just a bunch of listeners for the first time, the first three or four meetings we attended, and then pretty soon they started to ask us to come and join the older men, and that's how they told us what to do, how to play the rattle and the drum and everything. They started teaching us how to keep the beat with the drummer. And one thing that they didn't really appreciate was anybody fooling around when we were trying to learn. They always told us to take it serious when we got there and to try to learn as quick as we can.

We all started on the rattle, I guess. They taught us how to hold the rattle and how to beat it and how to keep time. For my part it didn't take me too long to learn it, because in myoid homestead where my grandfather used to stay, my grandfather was always si nging something; you know, practicing some of those society songs that they have, the ceremonial societies, different ones. He was always trying to have us two - that's my brother and I - try to sing along with him. A good many nights, especially in the winter, we used to sit and sing some of the ceremonial songs that he used to sing. But at that time I didn't pay much attention, so today I guess that's my misfortune. I never did pay much attention to what he was singing; now I really am sorry that I never did learn all that he used to sing.

I guess about two or three years after I started going to these meetings, there was someone I forget who it is) that asked if I knew the songs my grandfather Howard used to sing. I said maybe I could remember. Well, at that time they put me in amongst the older men and, well, I got kind of nervous the first time: I was so used to the rattle that I tried to tell them that I would rather use the rattle, and they said, no, you have to use the drum. They said you can never be a singer, not unless you can play the drum right. So, there I had to, I just had to learn.

They were playing the woman's dance songs. That's what those singing societies were always singing when they ever got together; they tried to outsing each other, I guess, in making up these woman's dance songs. So, they finally gave me the drum and they said to sit here; they said well, we want to hear some of your grandfather's songs if you can remember them all. They said at least one set anyway.

I was pretty nervous at first, and when I started singing, my voice kind of got shaky and I didn't know which way to go, or start crying or laughing. But after the first song, it was all right, and then the older folks kind of encouraged me to keep on and not to ... well, in the first place they said not to be bashful. They said, we can’t have you as a singer and you might as well forget it if you're going to be bashful or anything in that way. And well, after they gave me the drum, like I say, the first song I didn't know which way to go, either start bawling or go on and laugh with them. Well, I started it off and I pulled through pretty good.

It wasn't until, oh maybe when I was in my twenties, I guess, when I ever started trying to make my own songs up. And after I made up one and took it into the first meeting that we had and sang it, the old folks said that was pretty good. They liked the song, and they said to keep it up and just to keep on trying to fix up songs and make up songs; and that's how. I happened to keep on going, to keep making up songs. Some of the older men started passing away, and they wanted some new songs made up, and that's the way I happened to: right up till today, I can make up some of my own songs without any help from anybody else.

2

At first I'd forget the songs I made. Maybe somebody else would learn the songs, and when we'd get to these singing sessions, they'd kind of remind me of the songs that I had made up. At that time we didn't have no tape recorders or anything; we couldn't put it on tape, so I had to depend on somebody else to kind of remind me of the songs that I had made up.

Even today when I start making up songs, I'll take it maybe one song at a time, or when lucky I can make up two songs at once. Then I wouldn't try. to make a set (you know, six or seven songs) all at once, because it's easy to forget. That is why I never rush myself or try to make up a whole set in just that one night or just that one time. I'd rather, for my sake, try to make up one song maybe today and memorize it so I know just what it sounds like, and maybe two or three days later, make up another one. In that way maybe it takes me a week before I can make up a whole set.

It seems to me that the songs have come easier to me now than they did

when I first started that first song. I still don't know how a song comes out, but sometimes it's when you're thinking about one of the old songs ... this has happened to me. You know, I'm working off by myself on the end of the line up there in the shop, and all these late songs that I've made up have been made up right there in the shop, cause I'm all by myself on the end of the line and sometimes I ti .ink of the old songs - you know, just humming or whistling or whichever way I'm thinking about these old songs. Then pretty soon I try to make, up a new one. That's how I get my songs. Most of my songs. I call them my shop songs, because where they were mostly made up is right there in the shop when I'm working.

Then it all depends too how the man is feeling, what kind of a mood he's in. Sometimes I make up three or four songs 'and still remember them: a lot of times that has happened. If you're kind of happy, why you come right ahead and sing out a good song, but if you're kind of moody-like, you have a rough time trying to make a song out of it: you can't get it. This usually happens a lot of times with me when I start making up a new song. Sometimes it will just come right to my mind and I can sing it right off; then another time I try to make up a song and it takes three, four or five days before I can get it straightened out. There's some of the songs that we've made up that is, to my experience - there are some where the words kind of get jambled up amongst themselves and they can't straighten them out.

Well, if there's a little word or a sound that doesn't sound just right in the music, we try to cut it off or add a few words to it. Another thing that usually happens, when we do have a "new song, when we get down to the Singing Society where everybody else is along, maybe a lot of times the song will straighten itself out there, because whoever's there (maybe six or seven of us singing at the same time at this one meeting) could straighten it out for you. A lot of times it has happened with me. I'd start a new song, then I can't get it just right. Well, at the next meeting we have, I try to sing this song, and the rest of the group will help and straighten the song out for me. A lot of times this has happened. Maybe I just get the introductory part to it and then I can't get the middle part, then the rest of the society would try to straighten it out, and pretty soon we've got a new song.

Or getting back to sets again, if you make two songs or three songs that sound almost alike, you can easily lose your first song to your own mind cause you've already made up two or three others that sound almost alike and it gets complicated. If you're trying to teach these songs to the rest of the singing group, it's kind of hard. Lots of times it has happened, we thought we knew all the songs and we started singing the songs: we got through with one and the head drummer started to sing another one that sounded almost just like it, and by the time we got to the halfway mark of the song, everybody was singing something else, and that kind of made us sound silly. That's why I say if you're going to make up some songs, try to make a variety of them, with different pitches to the songs" not just make up one song and then pattern six or seven right after it.

My grandfather Chauncey, when he was teaching us to sing, he'd always

say when we start off with a song, if it's any kind of dance, he always said start off your singing real slow and then work up to the right tempo. He says always go according to how the dancers are doing: if they start dancing good, then he says that's where you're going to keep your speed. Like you start with this slow tempo and then work up to where the dancers are really enjoying themselves. He said never try to do it your own way, go according to how the dancers are doing, let them set your tempo. You can always notice when they start having a good time, when they start enjoying themselves, doing whatever dance you are singing to them: you know that that's just where you are going to keep your beat.

In composing songs too or in working them out, you always start off with a slow beat: in this way you can find out just where your mistakes are. Another

thing is (I always said this, and that's just the way I was taught) not to sing too high. You don't go right up into a high pitch so you can't reach the. right pitch to the song and the words that you have put into it, cause if you're going to teach it to the rest of the group, you have to sing it slow, so you can get the right pitch to the song and also get all the sounds in it. Now, if you start out real fast and sing high, the person you're teaching won't understand what you're trying to put over, while in this other way you take it real slow and they've got a better chance to understand what the song is, how it's going to sound, and the sounds that have been put into it.

As to the songs themselves, the style of the songs hasn't changed at all, I

don't think, from the old Singing Society to this one. I don't think that it's changed any at all, cause some of these songs that's being made up today are

from the oldtimers' songs. They're based on the oldtimers' songs. Some of the songs that I've made up - I just can't say which group it is, but maybe the ones I made up in '66 - there's two or three songs in there that I've based on my grandfather's songs. What I do is take a few words or the introductory part, and put in a few words and just a few different sounds to it. Almost the same melody. But not exactly the same and it hasn't got the same sounds in it,- in some places I've shortened it or added to it.

Some of the songs that I've made up from the oldtimer' songs I used the

introductory part, but in the second part to the song where the whole group is singing, then I've added different songs to it. Sometimes I've put together maybe two or three or four different old songs, just parts, and made it into one new song. Or I've added a few words to a song, or cut off some of it and put in new words to it and combined it with a different old song.

I guess we "modern singers," as they call us now, the ones that are making

up these new songs, really base our songs on the oldtime songs. I guess that's the whole basic idea, to try to revive some of the oldtime songs but still add on a few sounds yourself, just to keep the melody and the song kind of in remembrance, for memorial purposes more or less.

Some of these "woman's dance" songs that were made up come from other social dances, like the "fish dance": there's some songs that's made up from the fish dance and turned into the woman's dance. Like I say, you can take a few words out of a song and still add some on to it and make it into a woman's song from the fish dance. Like the "war dance": there's quite a few songs were made up from the war dance, from the different songs, and put into the woman's dance and a few words added on, and the tempo fell right into the woman's dance songs.

Then there's quite a few that's been from the sacred songs - like the Quiver Songs, the Changing Rib and the Death Chant - quite a few songs that's got just a little from these ceremonial dances put into the woman's dance. I don't know, these late years they just don't seem to care too much for being too strict on using these sacred dance songs, and they put it into the woman's dance songs. I guess they passed the stage where they were so strict against it - you know that years ago they didn't dare to use some of these songs and change it into a social dance.

I've got quite a few songs that I've made up, I never even taught to the

group because I figures it this way: it's got too much of the sacred songs into

it and I'd rather not put it out to public, because I know there are some people

that are really strict against having these sacred songs put into modern woman's dance songs. You'd get criticized why we have made up songs to have the public hear, so I usually try not to put any too much sacred songs into it. Maybe I do put in maybe a little sound here and there but just not too much.

There's quite a few songs too that's been made up from hillbilly music you

know, western hillbilly music. Sometimes you'll be listening to some of our old music, and then in just a little while you turn on your T.V. or put on a few recordings of western music - well then, sometimes you can get music combined from these, you can put the two ideas together and make one good song. From the western type of Indian music too: we have tried to make up a few songs from that.

Nowadays in making up new songs I use the tape recorder quite a bit. You know, I listen to these older songs, and that's where you get your new ideas from~ Tape recorders are an awful lot of help with that. Then maybe if you got an extra, empty tape, you can always put your new songs onto it. In that way you can't lose your original song that you have made up: like if you've made up a new song and try to remember it, oh maybe say two, three days after, and then try to sing it back, sometimes you lose it altogether. That has happened to me a good many times before I had the tape recorder. Then some of the other songmakers, you know, they take a notebook and write it down on notebooks. I've done that too, and I found that to be a lot of help. That's for the words naturally, not the music. We've never had any way of writing down melodies, just go by ear, I guess, as to what it sounds like. Well, in school I did actually go into it a little bit but, you know, after I got out of school I forgot all about how to read notes from a paper. What little music that I do know of - white music - well, it's mostly hillbilly songs, like "coming around the mountain" and all that, or "hand me down my walking cane" and all that. So that was all taken up by ear: if they put it in front of me in writing, I would never know how to read it.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

Poems and poetics