From 'Technicians of the Sacred' (expanded): The fiftieth anniversary pre-face, with a final note

[In preparation for the final publication Summer-Autumn 2017]

PRE-FACE (2017)

1

Something happened to me, now a full half century in the past, that has shaped my ambition for poetry up until the very present. Not to focus too much on myself, it was a discovery shared with others around me, of the multiple hidden sources and the multiple presences of poetry both far and near. I don’t remember clearly where — or when — it started, but once it got under my skin — our skin, I mean to say — that which we could hope to know as poetry drew in whole worlds we hadn’t previously imagined. Nothing was too low — or high — to be considered, but the imagining mind and voice, once the doors of perception were opened or cleansed, were everywhere we looked.

This also tied in to the search to create new forms of writing and thinking and to bring to light experiences and actions heretofore closed to us: a move that began with an earlier avant-garde and that we now repossessed/reclaimed as our own. A result of that — from the beginning, I thought — was an expansion of what we could now recognize as poetry, for which our inherited definitions had proven to be inadequate. In that sense that which was traditional in other parts of the world or buried and outcast in our own came across as new and unforeseen when placed within our own still too narrow framework. For myself, the discoveries, once I opened up to them, proved as rich in possibilities as what we and our predecessors had been creating for our own place and time. That so much of this came from an imagined “outside” or from long outcast and subterranean, often brutally repressed traditions was evident even before we named them as such.

Why did it happen then? Why in the 1950s and 1960s when I was first coming into poetry? The old explorers, the avant-gardists from the first half of the twentieth century who had gotten some of this rolling, had paused or retreated during the war (the second “world war” in the lifetime of some then among us), which in turn had changed everything around us. The early cold war that followed drove things/thoughts underground for some, while for others it brought the reassertion of a more conventional literary/poetic past. (That last was good, by the way, as a prod for actual resistance.) In the underground and at the margins, then, a new resistance was born in which the rigid past was again wiped clean and the new allowed to flourish. (Not the newness of novelty and fashion, as we saw it, but a newness that could change the mind and in so doing change the world — something shared with other arts and ways of thought and mind.) And with that came a kind of permission to remake the order of things and the changes began to come in helter-skelter; and as they did they changed the idea of what poetry was or could be in all times and places. For myself — early along — I turned to “reinterpreting the poetic past from the point of view of the present” — words I used in a manifesto I wrote in those heady times when so many of us were writing manifestos.

With this as my impulse I began to scour areas that had been closed to us as poetry — hidden, outsided, and subterranean — to discover what was clearly poetry but also forms of languaging that had never been within poetry’s domain. The first area I approached was what had for too long been labeled as “primitive” and “archaic” and that surfaced, when it did, (the “primitive” in particular) in specialized books that took up space in libraries and bookstores (but also in academic curricula) outside of poetry or literature as such. My own discoveries, once they started, came in lightning-quick succession, and as they did, they brought to light works in no sense inferior to what we sought or created as poetry in our own time and finally in no sense inferior to what had been delivered as the poetry and poetics of the normative “canonical” past. Furthermore they provided rich new contexts for poetry — not as literature per se but as a means, both public and private, for experiencing and comprehending the world, by which the visions of the individual (along with their translation into language) were at the same time what Mallarmé had called “the words of the tribe” (and Ezra Pound “the tale of the tribe”), words whose purification Mallarmé saw as the poet’s principal task. That the poems in question were largely oral — free of writing in the narrow sense — made them all the more intriguing & played into the draw we felt in our own work toward a new poetics of performance. (That the “tribe” in this sense was the human in all times and places is another point worth making.)

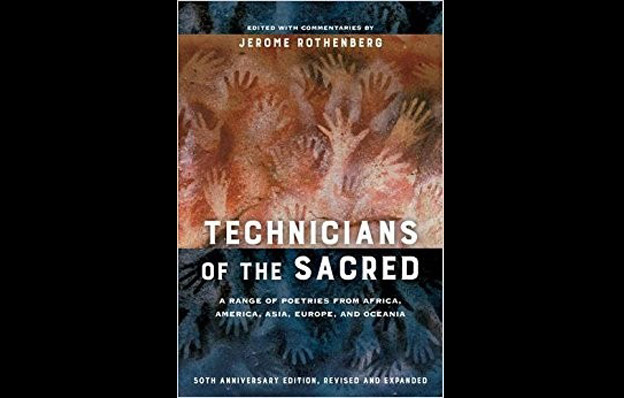

For this I found the anthology a nearly unexplored/undeveloped vehicle, one too in which I was given unchecked control during the heady days of the late 1960s, so that I could handle it as I would a large assemblage or a grand collage of words and images. That was what came to me anyway as I assembled Technicians, the idea of a book that worked through a series of juxtapositions and with a free hand that was given me to include whatever I thought needed including. And I found myself free as well to create a structure for the book and to include an extensive section of commentaries that could both point to the original/aboriginal contexts and to the relevance and resemblance of those poems or near-poems (Dick Higgins’s term) to contemporary works of poetry and art, but particularly to newly emerging experimental or avant-garde writing. It was that approach to the works at hand that allowed me to find poetry (or what I came to call poesis or poetic word and mind) in acts of language that had rarely been recognized as such. I was also able to drop the notion of the “primitive” as a kind of simplistic or undeveloped state of mind and word, and to begin the preface to the book with a three-word opening I can still adhere to: “Primitive means complex.”

2

In the original edition of Technicians of the Sacred in 1968, and again in the expanded 1985 edition, the three opening sections end with one titled “Death & Defeat,” which I’ve come to think of as a marker of the tragic if secondary dimension of the original work. The final poem in that section, however, was a small prophetic song from the Plains Indian Ghost Dance:

We shall live again.

We shall live again.

In the years since then, along with the continued decimation of many poetries and languages, there has been a welcome resurgence in others of what was thought to have been irrevocably lost. This has taken place both in indigenous languages (sometimes called “endangered” or “stateless”) and in the languages of conquest — in written and experimental forms as well as in continuing oral traditions, and as often as not showing both a continuity and transformation of the “deep cultures” from which the new poetry emerged. It is with this in mind that the old Ghost Dance song becomes a harbinger for me of what can now be said and represented.

My own experience here has been largely with the new indigenous poetries of the Americas, both north and south, but in the course of time I have also begun to explore similar outcroppings across a still greater range of continents and cultures. The new indigenous poets with whom I’ve had direct contact in mutual performance and correspondence write and perform in languages such as Nahuatl, Mazatec, Tzotzil, Zapotec, and Mapuche, among those in the Americas, while I can also draw on others (both poets and translators) in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, to maintain the global balance that characterized the earlier Technicians. I have also chosen to represent pidgins and creoles, as well as poetry written in languages like English and Spanish but tied in formal and semantic ways to the deep cultures from which they emerge.

In all of this it seems clear to me that when I speak here of “survivals and revivals” the reference isn’t to a static past but to works that are open both to continuity, however measured, and to necessary transformation. It is good to remember in that sense that change — of form and vision both — has been at the heart of the older poetries gathered here as well as of our own. As Charles Olson wrote, now some time ago: “What does not change is the will to change,” and it is in that spirit that revival appears here as renewal: to “make it new,” as Ezra Pound once had it, and the Emperor Taizong T’ang some thirteen centuries before him, and so cited. In the paradise of poets, to which I’ve alluded elsewhere, the old and the new are always changing places.

. . . . . . .

A FINAL NOTE. In the world as we have it today many of the indigenous and tribal/oral cultures foregrounded in Technicians of the Sacred are again under threat of disruption and annihilation. If the older colonialisms are less apparent than in the past, new forces unforeseen thirty years ago, both ethnic and religious, are threatening to wipe out vestiges of the alternate traditions and to eliminate those who remain their inheritors. In the process the deeper human past has also come under attack, rekindling memories of previous iconoclasms — the smashing of statues and the burning of books brought into a present in which the fear of difference and of change now reasserts itself. At the same time, and much closer to home, we have witnessed an upsurge of new nationalisms and racisms, directed most often against the diversity of mind and spirit of which the earlier Technicians was so clearly a part. To confront this implicit, sometimes rampant ethnic cleansing, even genocide, there is the need for a kind of omnipoetics that tests the range of our threatened humanities wherever found and looks toward an ever greater assemblage of words and thoughts as a singular buttress against those forces that would divide and diminish us. That the will to survive arises also among those most directly threatened — as a final and necessary declaration of autonomy and interdependence — is yet another fact worth noting.

Jerome Rothenberg

Encinitas, California

May Day 2017

Poems and poetics