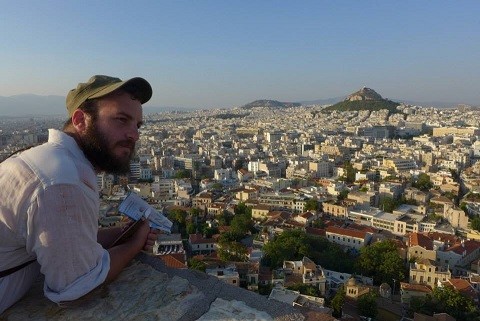

Stephen Ross: 'Question Answers Question: On Ariel Resnikoff's 'Between Shades'' & other matters

Ariel Resnikoff’s poems are wide open steps sunk in whiteness: their imprints lead far beyond themselves. They lead to Krasnystaw and Tel Aviv, Philadelphia and Montreal, antiquity and modernity, and back again. This openness, this generous range, makes Between Shades an unusually companionable book of poems. “I wanted to meet you / to tell you / you didn’t know me” reads the epigraph, summing up the ethics and poetics of this remarkable debut.

Between Shades inaugurates a multilingual Jewish American poetics that encompasses Hebrew, English, and Yiddish languages and traditions. The great strength of this unfolding project — the part that makes me certain it is the start of something important — is its refusal to essentialize Jewish history and language, favoring instead a decentered fluency. Resnikoff’s migrations, translations, and “avoidances” obey a scrappy, pragmatist principle of composition. The poems are not revivalist showpieces or sentimental fantasies but living mosaics born of a Jewish diaspora that is always estranged from itself anew, always “waiting / ‘to be’ / wandering.” In this sense, Resnikoff has begun to accompany the work of major predecessors in a larger field of poetics engaged with diasporic transmission — Nathaniel Mackey, for instance, whose ongoing long poems, “Song of the Andoumboulou” and “Mu,” perform syncopated Projectivist variations on diasporic themes. Robert Creeley also comes to mind as a model for Resnikoff’s fine intuition for the pacing of his lines. Take the opening of “Peh-etics (a midrash)”:

An efes

rises from the sand

of syncopated

speech songs

& sings

itself

transcribing

a fable de-

scribing

a stone.

The efes (Hebrew: “zero”) that rises here might also be a corruption of epes (Yiddish: “something”). This nothing-something grounds the poem in its own origin myth/midrash, a shifting foundation of “syncopated / speech songs” in which a false spelling can “transcribe” or “de-scribe” a world. Here we have not a poetics but a “peh-etics,” from the Hebrew word for mouth, “peh.” Resnikoff plays with Zukofsky’s famous interval of music and speech in these lines, filling the nothing with a tune made stonelike (cf. “Anew -20”).

As a scholar and translator of Yiddish and Hebrew poetry, Resnikoff has tuned his ear to exceedingly low and distant frequencies:

Each night begins

low as one speaks to a child

as one writes in chalk

on the street.

So begins “In Winter,” the opening poem in the chapbook. Like so much of Resnikoff’s work, these lines induce very fine double vision — should we take “as” as a simile here, or as a temporal marker? Poised in an interspace, a polyglot ghosthouse, the title and contents of this little book could also be read as between shades, the tunes and tones that occur in between (the craggy cover art by Rivka Weinstock aptly signals the volume’s complex textures). Or it can be taken as a weird simple sentence: Between shades. Yes, you feel “Between” expanding in these poems, coloring everything. Resnikoff’s poetics depends on the coexistence of all of these readings, and, more importantly, on this kind of inclusive reading — his words convene at the space and time of translation, where languages carry over and shade into each other.

You can feel it, for instance, in the way his poem, “not that,” flickers in and out of coherency:

Tohu ve-

tohu with out

waiting

"to be”

wandering

infinite

skin

over shade;

is finity

finally

the secret

skin of earth?

question answers

question

marks erasure

marks

structure as erasure

erases

strict skin stretches

between shade.

Not this

time

w/ clock

’s calloused hands —

not that

river’s

skin

over this.

Haim Nahman Bialik’s prophetic essay, “Revealment and Concealment in Language” (1915), provides the nourishing ground for this and other poems in Between Shades. Bialik, the father of modern Hebrew poetry, imagines language as a frozen river whose surface we walk across mistaking it for solid ground. This is the “concealment” of language, the fact that we attribute permanency to words that will soon “slip, slide, perish, / Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place, / Will not stay still,” as Eliot says. Yet the very life of language depends on the rise and fall of words, as necessity brings them into and out of existence. The frozen surface of the river sits precariously over the abyss of meaninglessness (Bialik calls it “blima”, or “without what”), yet prose writers step over the cracks in language and ignore what lies beneath — they skate on thin ice. Poets, however, gaze into the cracks and “reveal” the life and death of words (just as Kafka said that a book must be “an axe for the frozen sea within us”). Poets put us in touch with the futility of pitting words against the pure emptiness of things, even as they renew language that constantly atrophies. And they make us watch.

“Watch it!” Resnikoff repeats/warns in several of these poems. His broken-off reference to “tohu-bohu,” the elemental state of things in the beginning of God’s creation, conjures up Bialik’s terrifying “blima.” But this is not a poem about language’s decay into silence (Bialik is notably pessimistic about poetry’s final efficacy); rather, it’s a poem in the form of an ice floe — breaking up and melting away “with out” a trace, as skin, shade, and structure are put under inquisitive erasure. “is finity / finally / the secret / skin of earth?” he asks. Question answers question, and we come to understand that finitude, mortality, and “blima” are the necessary conditions for meaningfulness and exchange. The force of Resnikoff’s response to Bialik derives from this pressure we feel, somehow, in the fissures of this decreative poem — in the “between” where incomprehension and understanding abrade each other, where translation happens.

Resnikoff gathers and harmonizes a far-flung chorus of poetic voices. Among the tutelary spirits of Between Shades — including the Yiddish poets Avrom Sutzkever and Reuben Ludwig, the Israeli poets Zali Gurevitch, Gabriel Levin, Yoram Verete, and Dennis Silk, and the American poet Charles Reznikoff (a relative) — two stand out for having become Hebrew poets as adults: Harold Schimmel and Avoth Yeshurun. The American Schimmel switched from English to Hebrew when he moved to Israel in the 1960s, and his work over many decades at the center of Israel’s multilingual poetry community forms an essential foundation for Resnikoff’s practice. I would highlight in particular Schimmel’s groundbreaking translations of Avoth Yeshurun, a poet little-known outside Israel whose importance to modern Hebrew poetry arguably matches that of Paul Celan for German. Born Yehiel Perlmutter in a Ukrainian shtetl on Yom Kippur in 1904, Yeshurun left his Yiddish-speaking family’s later home in Krasnystaw, Poland, for British Mandate Palestine in 1925, where he lived an itinerant life among Jewish and Arab communities. After he left, he would never again see his family, who were murdered at Belzec. In 1948 he changed his name to the Hebrew Avoth Yeshurun, which might be translated as “the fathers are watching” and, if translated back into Yiddish, as “little boys are watching us.” His reasons for choosing this name are complex, and his work always pivots him back toward eastern Europe where he watches his family watching him. Here is Resnikoff’s version of a very difficult Yeshurun poem, “all who come from there”:

from whence you go

& to where you come

I won’t arrive

at anyplace.

b/c all my goings are

toward the from-where

b/c the nothing is.

The nothing exists.

in the non-existence — write in logic. clear.

exact:

all that does not exist in existence.

in nothing, exists

all that exists.

all who come from there,

like a dog I’ll smell their clothes.

those, their smell, my father & mother,

brothers & sister stand

straight in my eyes

& all Krasnystaw stands at the windows.

It is Yeshurun’s manner to slice language down to the bone, then past the bone. Like Bialik, he is a master of negativity, yet he defers Bialik’s full-bodied sublimities in favor of a hybrid language that rattles, gasps, stutters, breaks off, and chokes in a Hebrew shot-through with Yiddish, Polish, Arabic, and other languages. Here, too, is a poetics of watching: “my father & mother, / brothers & sisters stand / straight in my eyes / & all Krasnystaw stands at the windows.” This is a different kind of watchfulness, though, than that of Bialik, a keen attentiveness conditioned by guilt and mourning. Resnikoff does an excellent job in this translation of getting across the shorthand flavor of Yeshurun’s work — the lower-case title and text, the ampersands, the b/c’s. What kind of a poem is this? It begins with a garbled reference to Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) 3:1, “Know from whence you came, and where you are going.” The poem begins by falling into the cracks of its own unusable language. Nothing comes from nothing, and there is no there there, in Krasnystaw. I think Resnikoff responds very movingly in Between Shades to the contingency of this poem, the way it obeys what Robert Duncan calls “the unyielding Sentence that shows itself forth in the / language as I make it.” Language is not transparent, and form is not fetishized. Words are material things we make make meaning. When Resnikoff plays with the sound and sense of the Hebrew “efes” in “Peh-etics,” we hear behind it Yeshurun’s “rattling / mouth // garbled / running.”

With this debut, Resnikoff lays the groundwork for a major life-long poetic project of “gathering from the air a live tradition” — a multilingual Jewish-American poetics that we will be watching very closely.

Poems and poetics