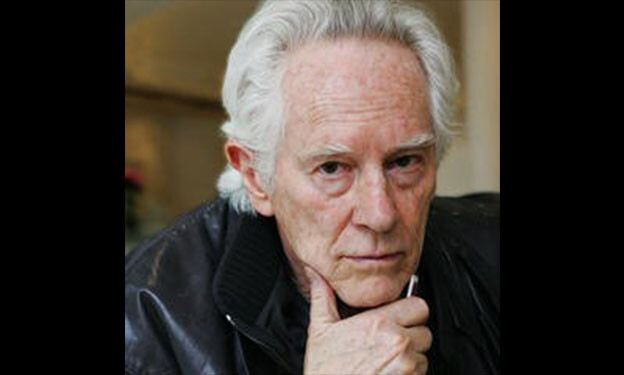

Jerome Rothenberg

For Michael McClure, a memorial and tribute

Written as introduction to a reading 15.iv.2000 at D.G. Wills Books in La Jolla, CA

I think that Michael McClure and I first came together when he helped me to see — in 1968 or 1969 — the implications of what I had worked out on my own in Technicians of the Sacred. I had, for years before that, been gathering materials and texts that involved (specifically) outcroppings of poetry in areas and cultures outside the accepted literary mainstreams. From Michael — and from others like Gary Snyder — I became aware of how many shared interests that involved and of how many transformations had already taken place, beyond the page (so to speak) and into the wide world outside. I knew Michael McClure’s poetry before that and had inserted poems of his into Technicians (the Ghost Tantras that he wrote in “beast language”) as parallels to kindred ancient works from aboriginal & mantric sources (and to the sound poems as well of early modernists like Hugo Ball and Kurt Schwitters). His work throughout was electrifying to those of us watching — with great joy in the discovery — the poetry that was arising then among our own contemporaries. The “beat surface” — which he, like others, “scratched” — was an important part of this, but there were other surfaces and other depths, as well. In McClure’s case there was from the beginning a mix of highly charged language (visceral, sexual, what he would later call “mammalian”) with an often overriding gentleness of tone and gesture. In the voice of those poems I heard the voice of someone really speaking, but speaking in — what should we say? — a bard’s voice, with a touch, a memory of Blake and Shelley: poets who had moved him in the past. This sense of voice and body (but really body-mind as one) led him also into an amazing series of theatrical works, like the often-acclaimed and often-banned The Beard, and on its musical side, to interactions with the likes of Bob Dylan and The Doors (and to his later collaborations over the years with keyboardist Ray Manzarek). Now, all this might mask, as it too often does with others, the full sweep of McClure’s work. He is both a latterday Romantic — in the best sense — and a sharer in an experimental modernism that has produced our greatest poetry — worldwide — over the last hundred and more years. His grasp of poetry — and art as well — goes back to high school days and first discoveries of surrealists and dadaists who came before him, but also to the work of contemporaries who shared with him a front place in the heyday of the San Francisco Renaissance. And beyond the poetry as such, he is a devoted student of a range of knowledge in both the arts and sciences — the biological and anthropological in particular — which feeds the poetry in turn and brings about a genuine and very unique lyricism of bio-particulars (meat science as he calls it) and the finest celebration that I know of a universe of living forms.

The recognition of this central aspect of his work has nowhere been better explained than by Francis Crick, our fellow San Diegan and a longtime admirer of McClure’s, who said about him: “What appeals to me most about Michael’s poems is the fury and the imagery of them. I love the vividness of his reactions and the very personal turns and swirls of the lines. The worlds in which I myself live, the private world of personal reactions, the biological world (animals and plants and even bacteria chase each other through the poems), the world of the atom and molecule, the stars and the galaxies, are all there, and in between, above and below, stands man, the howling mammal, contrived out of ‘meat’ by chance and necessity. If I were a poet I would write like Michael McClure — if only I had his talent.”

As a poet myself I can't go quite that far, though I would have been pleased to be the one who once proclaimed “I am a mammal patriot,” or with a voice akin to Blake and Dickinson (and in a beautifully shaped series of elegantly centered lines, to top it off):

HOW

SWEET

TO

BE

A

ROSE

BY

CANDLE

LIGHT

or

a

worm

by

full

moon.

See the hop-

ping flight

a cricket makes

Nature loves

the absence of

mistakes.

or, best of all, to be the poet who spoke to (and through) the raging beast and said:

GOOOOOOR! GOOOOOOOOOO!

GOOOOOOOOOR!

GRAHHHI GRAHH! GRAHH!

Greeeeee

GRAHHRR! RAHHR! GRAGHHRR! RAHR!

RAHR! RAHHR! GRAHHHR! GAHHR! Hrahr!

BE NOT SUGAR BUT BE LOVE

looking for sugar!

GRAHHHHHHHH!

ROWRR!

GROOOOOOOOOOH!

And the following, as my own tribute to him, written as our century — the twentieth — was slowly fading out:

PROLOGOMENA TO A POETICS

for Michael McClure

. . . . . . .

Poet man walks between dreams

He is alive, he is breathing freely

thru a soft tube like a hookah.

Ashes fall around him as he walks

singing above them.

Oh how green

the sun is where it marks

the ocean.

Feathers drift atop the hills

down which the poet man

keeps walking, walking

a step ahead of what he fears,

of what he loves.

. . . . . . .

Why has the poet failed us?

Why have we waited, waited for the word to come again?

Why did we remember what the name means

only to now forget it?

If the poet’s name is god how dark the day is

how heavy the burden is he carries with him.

All poets are jews, said Tsvetayeva.

The god of the jews is jewish, said a jew.

It was white around him & his voice

was heavy,

like a poet’s voice in winter,

old & heavy,

crackling,

remembering frozen oceans in a summer clime,

how contrary he felt

how harsh the suffering was in him,

let it go!

The poet is dreaming about a poet

& calls out.

Soon he will have forgotten who he is.

. . . . . . .

Speak to the poet’s mother,

she is dead now.

So many years ago she left her father’s clime.

His father too.

The tale of wandering is still untold,

untrue. The tale of who you are,

the tale of where the poem can take us,

of where it stops

& where the voice stops.

The poem is an argument with death.

The poem is priceless.

Those who are brought into the poem can never leave it.

In a silver tux the poet in the poem by Lorca

walks down the hall to greet the poet's bride.

The poet sees her breasts shine in the mirror.

Apples as white as boobs,

says Lorca.

He is fed the milk of paradise,

the dream of every poet man

of every poet bride.

The band plays up

the day unstops & rushes out to greet

another night.

. . . . . . .

Is the black poet

black?

And is the creation of his hands & throat

a black creation?

Yes, says the poet man

who wears three rings,

the poet man who seeks the precious light,

passes the day beside a broken door

no one can enter. Hold it shut,

the god cries & the jew rolls over

in his endless sleep.

Gods like little wheels glide past him

down the mountain road where cats live

in a cemetery guarded by his father’s star,

a poet & a bride entangled in the grass,

his hands are black

his eyes the whitest white

& rimmed with scarlet.

Hear the drumbeat,

heart.

The blacks have landed on the western shore

the long lost past of poetry revives.

. . . . . . .

Our fingers fail us.

Then tear them off! the poet cries

not for the first time.

The dead are too often seen filling our streets,

who hasn’t seen them?

A tremor across the lower body,

always the image of a horse's head

& sandflies.

A woman’s breast & honey.

She in whose mouth the murderers stuffed gravel

who will no longer speak.

The poet is the only witness to that death,

writes every line

as though the only witness.

Poems and poetics