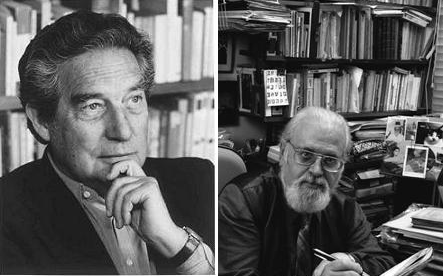

Jerome Rothenberg: Translation, transcreation, & othering, an homage to Octavio Paz & Haroldo de Campos

[NOTE. The following commentary was written to accompany a series of poems commisioned & prepared for "Trans-Poetic Exchange: A Colloquium on Haroldo de Campos and Octavio Paz's poem ‘Blanco’” at Stanford University, January 29-30, 2010. An instance of what de Campos called "transcreation" and I call "othering," the method employed here is one I've used in The Lorca Variations & elsewhere, drawing on translations of Paz’s & de Campos’s writings & moving on therefrom. Both poems & commentary are scheduled for publication as part of a full-scale proceedings of the 2010 colloquium, news of which will follow shortly. (J.R.) ]

1/

The crux of the matter here was Haroldo de Campos’s theory and practice of transcreation, something that was very much on my mind since our first meetings in Europe nearly two decades ago. For me too – and I believe for Haroldo as well – this brought up the question of my own practice with translation in Technicians of the Sacred (1968) and beyond, as well as the still larger dimension of what I had come to call “othering” and, more narrowly, “total translation.” Like him I came more and more to think of translation as the foundation for the larger part of what I and others had been practicing as poetry – at least that our treating it as such raised some productive questions about the nature of poetry and of language over all. (This was also at the heart of the noigandres experiment, for which Haroldo of course was one of the prime movers.) And this centrality of translation was hammered home as well by Octavio Paz, so that the conjunction of De Campos and Paz in the present gathering made translation, transcreation, and othering the dominant themes for me as I approached it. For this of course, Octavio’s “Blanco” and Haroldo’s transcreation thereof were the twin works open for our consideration.

My strategy here was to turn, as Haroldo had before me, to the original “Blanco,” so as to further the earlier act of transcreation with a transcreative work of my own. I looked in doing so to a form of othering that I had begun to practice two decades before – in a series of poems, “The Lorca Variations,” derived from the vocabulary of my own translations of García Lorca’s early Suites. In my “variations” I systematically used all of Lorca’s nouns (in my English translation) as nuclei from which to compose new poems. Moving from poem to poem I arranged the translated nouns in four or five columns and proceeded to link the words in something like reverse order, with results like the following, both Lorca and not-Lorca, both mine and not-mine:

The Lorca Variations XV

“Water Jets”

1

If death once had a face

the water from this water jet

has wiped it out,

the August air has left no trace of it,

like other fountains

or other faces from your home town

that the sunlight & the water jet

drive from your room.

Things leave our eyes no boundaries here

other than dreams, no dreams

still precious to your heart,

its carved interior shot through with corners,

into which a grapevine grows,

fed by the water jet your fingers

once turned on, made it a place of clouds,

the perfect death’s head still inside it,

& that a water jet wipes out.

2

It’s night.

In the garden our hearts have turned blue.

A maid opens the water jet, lets water & roses spill out.

A century passes.

Pianos circle the earth, dark swords slice arteries.

No dust on your windows, just blood.

In the garden four gay caballeros trade swords.

A cloud breaks apart & starts quaking.

It’s night.

And for Paz’s “Blanco” the following:

BLANCO 2: A VARIATION IN FIVE SEGMENTS FOR OCTAVIO PAZ

1. A clarity | of all the senses | lingers | leaving on the mouth & face | a white precipitation | sculptures crystal-thin | blank space | translucid whirlpools

2. Is it a pilgrimage | that brings us | dancing in a ring | into a forest | where our thoughts | are white | the only signs | our steps | that break the silence

3. Green would be better | a slim defile | through which we pass | an archipelago | the shadow of a syllable | a white reflection

4. Is it red | or is it blue | this dazzlement | that blinds us | numbers | dancing in the void | like things | a final clarity | no longer white

5. Thoughts fade | winds cease| forgetfulness erases truth | there is a deeper music in the words we speak | yellow isn’t white | & amethyst | is just a color

2/

If the Blanco variations published here and written for the occasion of the Stanford conference were my homage to Paz, in the case of Haroldo de Campos I brought forward a series of poems composed several years before and displaying a quite different form of othering. That series, which I called “Antiphonals” for obvious reasons, was part of a commission from Francesco Conz, a great collector and publisher of Fluxus and other avant-garde art and poetry, for poems to be written by hand on a series of large colored photo portraits of Haroldo. As my contribution to what was conceived as a group tribute, I took phrases & lines from English translations of Haroldo’s poetry & responded to them with loosely rhymed soundings of my own. I then handwrote the poems pair by pair onto a black left margin on each of the photographs. In the typographical version, Haroldo’s words appear in italics, while mine are shown in roman type. For me at least, the resultant work has the feel of translation/transcreation – as still another instance of othering.

Two such instances follow:

the malice

of the

mastery

the chalice

of her

chastity

.

weary

weary

weary

and a fury

dreary

dreary

dreary

in missouri

All of this of course is not unfamiliar to other poets and is part of what we mean when we speak not only of translation as such but of related procedures such as collage and appropriation. I am willing enough to extend all of these techniques so as to consider the consequences of viewing all our works (even the most “original” and “self-expressive” ones) as aspects of such a deeply human procedure. Language is and always has been an aspect of our work in common, and there is a sense here, as I’ve stated often before, in which all translation and all of its related acts involve a kind of implicit collaboration – at least in the mind of the translator. I am very much aware of this, however one-sided it may often seem, and I have sometimes let myself believe that all our writing, all our poetry, is an activity shared by all who are the users and makers of our common language. This idea of a communally driven poetry – of the poem, however individual or unique, as simultaneously what Pound called “a tale of the tribe” – has held my attention even when I felt it to be false. In a world in which that kind of unity is again under fire, I would continue thinking in those terms, wherever it may take me.

Poems and poetics