Toward a poetry and poetics of the Americas (15)

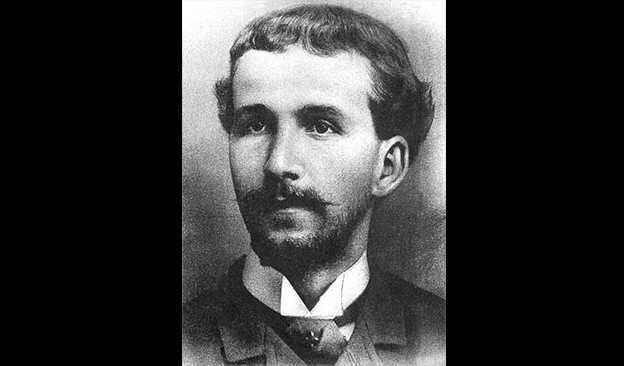

Two poems by José Asunción Silva

Translations from Spanish by Jerome Rothenberg

Nocturne III

A night,

A night thick with perfumes, with whispers and music, with wings,

A night

With gloworms fantastically bright in its bridal wet shadows,

There by my side, pressed slowly and tightly against me,

Mute and pale

As if a presentiment of infinite sorrow should stir you

Down to the secretest depths of your nature,

A path with flowers crosses the plain

Where you traveled,

Under a full moon

Up in the deep blue infinite skies

Its white light scattered,

and your shadow too

thin and limpid,

and my shadow

That the moon’s rays projected

Across the sad sands,

Where both were conjoined

and were one

and were one

and were one immense shadow!

and were one immense shadow!

and were one only one immense shadow!

That night

All alone a soul

Filled with infinite sorrow

With your death and its torments

Cut off from your self, by the shadow, by distance and time,

An infinite blackness

Where our voices don’t reach,

Mute and alone

On the path I was traveling …

The sound of the dogs as they bayed at the moon,

The pale moon,

and the croaking out loud

of the frogs …

I felt cold, felt the coldness that came from your cheeks

In the alcove in back, from your breasts and the hands that I loved

Under sheets white as snow in the death house!

A coldness of graves and a coldness of death

and the coldness of nada …

and my shadow

that the moon’s rays projected

was drifting alone,

was drifting alone,

was drifting alone through an unpeopled wasteland!

and your shadow, agile and smooth,

Thin and limpid,

As on that warm night in dead spring,

That night filled with perfumes, with whispers and music, with wings,

Came near and made off with her

Came near and made off with her

Came near and made off with her …

Oh the shadows brought together!

Oh the shadows of our bodies joining with the shadows of our souls!

Oh the shadows sought and brought together in the nights of blackness and of tears

…!

ZOOSPERMOS

The world-renowned scientist

Cornelius Van Kerinken

who enjoyed a sizable

practice in Hamburg

and left us a volume

of some seven hundred pages

on the liver and kidneys,

was abandoned in the end

by all of his friends,

died in Leipzig demented,

dishonored and poor,

because of his studies

at the end of his life

on spermatozoa.

Bent over a microscope

that cost him a fortune,

unique and a masterpiece,

from a London optician;

his sight bearing down,

his hands shaking badly,

anxious, tight, motionless

focused and fierce,

like a colorless phantom

in a low voice he said:

“Oh! look at them running

how they’re moving and swarming

and clashing and scattering:

these spermatozoa.

Look! If he weren’t

lost and vanished forever;

if fleeing down roads

that no one remembers

he finally managed

after so many tries

to change into a man

his life still before him

he could be a new Werther

and after thousands of torments

and exploits and passions

would knock himself off

with a real Smith and Wesson,

that spermatazoon.

And the one just above him,

a hairbreadth away

from the so-to-speak Werther,

at the edge of the lens,

could end up as a hero

in one of our wars.

Then a statue in bronze

could serve as a tribute

to that unbeatable winner,

that bona-fide leader

of soldiers and cannons,

Commander in Chief

of all of our armies,

that spermatazoon.

The next one here might be

the Gretchen to some Faust;

and another, higher up,

a noble-blooded heir,

the owner at twenty-one

of a million or so dollars

and the title of a count;

still another one, a usurer;

and that one there, the small one,

some kind of lyric poet;

and this other one, the tall one,

a professor of some science,

will have written a whole book

about spermatazoa.

Good luck and gone forever

you small dots and small men!

between the two thick lenses

of the giant microscope,

translucent and diaphanous,

Good luck, you shimmying

zoosperms, you will not grow

over the earth to people it

with further joys and horrors.

In no more than ten minutes

you’ll all be lying dead here.

Hola! spermatazoa.

Thus world-renowned scientist

Cornelius Van Kerinken

who enjoyed a sizable

practice in Hamburg

and left us a volume

of some seven hundred pages

on the liver and kidneys,

died in Leipzig demented,

dishonored and poor,

because of his studies

at the end of his life

on spermatozoa.

commentary

by Heriberto Yépez

“Leave your studies & pleasures, your / vapid lost causes, / &, as Shakyamuni once councilled, / hide your self in Nirvana.” (J.A.S. from Filosofías). And again: “When you reach your last hour, / your final stop on earth, / you’ll feel an angst that can kill you — / at having done nothing.”

(1) José Asunción Silva was a careful reader of Bécquer and Verlaine, Martí and Poe, Campoamor and Baudelaire. He was convinced he needed to combine traditions, though he had his mind on an obscure and introspective nothingness that, according to him, transcended all of them. Silva was a deep researcher of the dark aspect of the soul.

After a year abroad in 1886, he returned to his native Bogotá. In Europe his poetry had evidently taken a significant turn. He had met Mallarmé in Paris, an encounter that marked him deeply. In Silva, European romanticism was reinvented, though he didn’t intend to escape the archetype of the Romantic poet that he explicitly wanted to adapt. Silva’s life is full of sad anecdotes. An important part of his work was lost in a shipwreck and soon in his adult life he had to face all sorts of difficulties. He was a man of an intense emotional life. He believed poetry precisely was an investigation of “complex feelings.”

About him the Mexican avant-garde poet José Juan Tablada would write: “Silva does not have a biography but a legend. He lived yesterday, is our brother today, but he goes back still further, caving in the past.” His work constructs a space-time that can be best described using images such as Vallejo’s “alternative cavern.” He knew his “night” referred not only to the depth of his interior world but also to the artificiality of his visions.

(2) Soon after the death of his sister Elvira, Silva wrote (in 1892) his most enduring poem “Noche.” also known as “Nocturno III.” The intensity of the piece provoked speculations around a supposed incestuous relationship with his sister. We could easily get lost in the biographical aspects of Silva’s figure. But we need to focus, at least for a moment, on this poem, so important in the development of later poetry in Spanish, not only as a forerunner of modernismo but as a structural inspiration for later avant-garde writing.

“Nocturno III” comes from an unusual extension of voice that even visually creates an unseen pattern of lines. One can sense in Silva’s “night” the process of contacting his underworld and the intermittent flow and rupture derived from this contact. It is a chant to the night and to the obscure unity of a mysterious duality that does not lead to death, but is death itself. This poem in particular possesses a structure that would reappear (reinvented) in some of Neruda’s pieces, for example, but most importantly it deals with an alliance to obscurity and a dialect of rhythm and breakage, sound and visual play, that is still haunting.

Silva is also the author of a novel titled De sobremesa. In 1896 Silva committed suicide shooting a bullet directly into his heart.

Poems and poetics