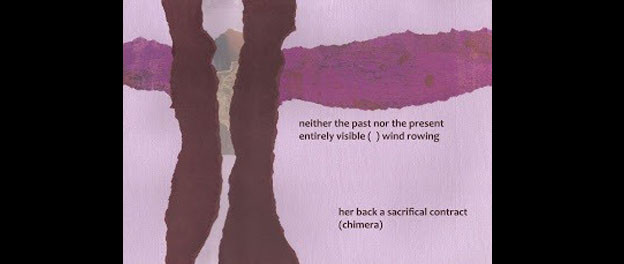

Marthe Reed: from 'Ark Hive' (forthcoming), printed here as a memorial and tribute

[editor’s note. In the wake of Marthe Reed’s sudden and unexpected death earlier this month, I am opening Poems and Poetics to a commemoration of her work and spirit through the posting of an excerpt from a new book now awaiting publication. I had known Marthe Reed first as my student at UCSD San Diego and later as a dear friend and greatly admired poet. I would surely have published the following work (“Here and Not”), so expressive of her poetics and her project as a whole, under any circumstances, but coming so soon after her death, the sense of loss colors whatever reading I now give it. A fragment comes to mind from one of the poems in Ark Hive called “Threnody” [lament], also in this volume:

moving

displacements

twist into light

warm water’s

melancholy weather

like an afterimage of rain

where I find myself

bruised awake

giving way

Writes Amish Trivedi, assistant editor of this page and fellow poet, by way of introduction and tribute:

“The text presented here is from Marthe’s Reed’s Ark Hive, forthcoming posthumously from The Operating System. A poetic approach to life in south Louisiana, it’s no wonder that Reed quotes poet C. D. Wright at the start of the work as Wright’s work covering south Louisiana could no doubt be seen as a necessary prerequisite to Reed’s own project. In the opening pages, Reed approaches her predicament as if she were a researcher placed in a foreign land, situating herself among her surroundings, in the midst of a condition of place that is both physically distant and so very different from the places she had previously lived. From there, she leans into language, the language of water, of floods and earth reclaimed, only to be lost again as the seasons change in places that are far away, the words occasionally scattered across the pages like the silt that drives the Mississippi water to the Gulf of Mexico.

Ark Hive is the memoir of a person but it is also the narrative of a place, how it came to exist in the time that Reed was living there. We traverse the geography as we traverse the culture, one affected deeply by Hurricane Katrina and also the governmental response to that disaster. Here the language is erased, something that nearly happened somewhere between the storm and the individuals in charge of helping those caught in the middle. The book ends in another crisis — one for her as ‘nomadic wanderer’ and for the Louisiana coast, changed by the oil spewing from the bottom of the ocean that no one could seemingly stop.

While south Louisiana went through change, so did Marthe, this project tying those changes together, through her own choices of form and thought and language to a kind of self-identification through place, through shared traumas. This was a place once foreign that by the end is reflective of the journey of an individual poet among many who witnessed along with her.

Marthe Reed passed away on April 10th with Ark Hive scheduled as part of The Operating System’s 2019 ‘cohort,’ a word choice Marthe would no doubt have loved for its sense of comradery among writers and those who publish them, something she embodied for the rest of us.”]

Here and Not

However briefly I find myself in a strange place, I am intent on locating myself; where I came from at this point is portable; I carry it with me. — C. D. Wright

I was not there, yet I was there. — Ernest Gaines, A Lesson Before Dying

“Hub City,” center of Acadiana and straddling the Vermillion River, Lafayette lies almost due west of New Orleans across the Atchafalaya Basin. The basin, formed by the Mississippi as it laid down successive depositional lobes — Sale-Cypremort, Teche, and Lafourche — the great river switching back and forth finding the shortest route to the Gulf, giving rise to the whole of south Louisiana along the way. If not for the Army Corps of Engineers, its locks and levees, the Mississippi would now enter the Gulf by way of the Atchafalaya Basin and River.

My own route to Lafayette took the long way around: from Western Australia by way of Indiana, by way of San Diego, by way of Providence, Rhode Island, by way of San Diego earlier on, by way of Central California farm, an almond orchard in the countryside near Escalon. Neither here nor there, though here nonetheless: eleven years in Lafayette. When the jet landed in New Orleans, July 2002, stepping outside our eye-glasses immediately fogged up, as when in winter elsewhere we had come in from the cold. Summer humidity in Louisiana does not rest, the evenings no less unrelenting than midday. Tomato plants give up come July, the heat of mid-morning through most of the night sapping their resilience. Wake up, stand outside in the shade, sweat. Summer teaches us to slow down, have a sno-cone: plan to exercise come winter. Here in the wet, green tangles everywhere in summer. Up telephone poles and along the wires, across bridges, through gaps in the asphalt and cracks in the sidewalk (where there are sidewalks, sometimes), wherever earth gathers unbidden in human spaces. No rooting it out. Green. Green verges beside roads and highways, ferns profligate across oaks branches, moss over wood railings, over brick and rendered walls. Green rice fields, green bottomland forest, green coastal seas, green marsh grass — prairie tremblant — shifting in the wet.

Being in, though not of this place, by what permission do I write about it, here where I live(d)? After school, I listen to the men cutting hair at Ike’s Barber Shop, my child sitting high in the red chair listening also. Their talk flows around me, unfathomable, a French I can neither parse nor piece together, though it holds me still listening, as to the sound of water tumbling over root and rock. I overhear folk chatting in Poupart’s Bakery, cups clinking against saucers, while I order epi or baguette, the beignets and hand pies calling from the counter. Français cadien. Old world French, 17th Century and code-switching French, ‘Cadien. Mixed. Chatoui. Rat du bois. Bequine, plaquemine, rodee. Suce-fleur. Up the bayou. Make the bahdin. Five million nutra rats eating up the coast.

A friend invites us to dinner, her home a circle of rooms leading one into the next. No center, only the circuit: kitchen to living room to bedroom to bedroom to back room to kitchen. Did you miss me? The porch ceiling, painted “haint” blue, hints at sky warding off spirits who cannot cross water —Gullah knowledge carried across the south. Blue ceilings guard against insects also, mosquitos plying the air, owning the evening.

I walk the woods spying for raccoon tracks (chatoui, cat yes), armadillo burrows, passerine fliers stopping over. Phoebes, flycatchers, nuthatches, sparrows. I purchase guidebooks for native trees and plants, native birds. In my neighbor’s yard, bottle-brush hosts brown thrashers and ruby-throated hummingbirds; I once spotted a Baltimore Oriole, orange-and-black-bodied, among it brushes. Magnolia and live oak line the median of our street. In spring, the astonishing scent and size of magnolia blossoms, their sprawling, creamy tepals circling the green and gold “woman house” (gynoecium) and spikey yellow “man house” (andoceum). Seed-making and germination. Coming to know this place by means of books and my feet, listening: Atchafalaya pronounced uh-CHAF-uh-lie- uh not ATCH-uh-fuh-lie-uh. Puh-CAHN not PEE-can. Sound of squirrel scolds rain from the oak trees, cher become sha.

Lafayette is Catholic country, a tradition familiar and not, my mother’s Episcopalian faith never rooted in me, nor Judaism in my husband. At school, our children navigate the shoals of piety among the faithful, vegetarianism among the carnivorous. Kin-less also, we orbit the edges of extended families upon which community takes form here. Outsiders-in-the-midst. Mike digs in, devouring mounds of boiled crawfish or trays of oysters half-shelled, drenched in garlic and tabasco, washed down with a bottle of LA 31. Oysterloaf in New Orleans, rabbit plate-lunch in Lafayette, hot boudin at the roadside stop. Praising their grandmothers’ rice and gravy, dirty rice, or corn maque choux and shrimp, my students gape in disbelief when they discover I do not eat meat or seafood: “But what do you eat?” they wonder, amazed. Often Lebanese food, heritage of waves of Maronite immigrants from what would eventually be known as Lebanon. Local eggs, mirlitons, Cajun Country Rice™, roasted chilies and grilled okra, cornbread, collards, Creole tomatoes, muscadines. Sweet corn, sweet corn, sweet corn and peaches. Pickled okra, cheese grits or Zea’s sweet corn grits with roasted red pepper coulis. Wild blackberries and pick-your-own blueberries in summer, oranges, Meyer lemons, satsumas in winter.

Writing Louisiana, outsider-inside, poles of affection and alienation push and pull against me. An astonishing and richly diverse region, both culturally and ecologically, its inhabitants have sold paradise for oil and gas money, ignored the most vulnerable, allowed schools, hospitals, and the poor to bear the burden of economic crises, crises often manufactured through tax-giveaways to the affluent and corporations, spending one-time monies as if they would last forever. Paradise is poverty-stricken, imprisoning its citizens at the highest rate in the country: 816/100,000 — far greater than even Russia’s 492. Its waters, polluted and poisoned, its coastlines washing away at perilous rates — 2000 square miles in just 80 years. By 2050, if global temperatures rise just two degrees, erosion combined with Antarctic ice melt will reduce New Orleans to an island tied to land by a bridge-cum-highway, the state’s coastline a series of slender fingers in the sea: New Iberia, Morgan City, Thibodeaux perched upon the flood.

Still, who am I to rebuke or challenge, to call into question? Is this my place, too, outsider-inside? I lived in south Louisiana eleven years, eleven years in love and in despair. Do those years cede me ground to write? No Cajun, no Creole, no Louisianan by birth or adoption? By what permission? Only love, heart broken open again and again.

Sky over New Orleans, that endless expanse of blue and cloud, high and wide as all the earth, or so it seems. Walker Percy had the way of it, “a sketch of cloud in the mild blue sky and the high thin piping of waxwings comes from everywhere.” The soft mutterings of the Gulf, water lapping sand or mud, Kate Chopin’s “voice of the sea whispering through the reeds that [grow] in the salt water pools,” “white clouds suspended idly over the horizon.”

The mass of vegetation composing a swamp: Lake Martin’s bald cypress, water tupelo, and live oaks draped in Spanish Moss, seeds afloat on the water. Elm, ash, pecan, buttonbush, palmetto. Blue-eyed grass and red buckeye. Invasive bladderwort, water hyacinth, fanwort, coontail, duckweed, and hydrilla tangle the water where native lotus, yellow and blue flag iris, red iris and water hyssop thrive also. Powdery thalia. Sedges all along the lake’s margin. The extraordinary population of birds inhabiting the lake: White Ibises, Anhingas, Neotropic Cormorants, Snowy Egrets, Little Blue Herons, Green Herons, Great Egrets, Roseate Spoonbills, Tricolored Herons, Cattle Egrets, Yellow-crowned Night-Herons, Black-crowned Night-Herons, and Great Blue Herons. Common Moorhen and American Coots, Belted Kingfishers. Along the levee trail: Pine and Yellow-throated Warblers, Northern Parula, White-eyed Vireos, and Indigo Buntings; flycatchers, woodpeckers, nuthatches, wrens. In the air and in the woods, Sharp-shinned Hawks, Cooper’s Hawks, Broad-winged Hawks, Red-tailed Hawks, Barn Owls, Eastern Screech-Owls, Great Horned Owls, Barred Owls, Common Nighthawks. All these species and myriad others, the swamp a-thrum with life.

At Jefferson and East Main Streets, sunset rises over Pat’s Diner, saffron and orange tumult of clouds towering. Cajun shaved ice stands: watermelon, raspberry, orange, and pink lemonade — or wedding cake, guava, piña colada. Drive-through daiquiri stands where, with a quick bit of tape on the lid, you’re good to go. Fishing camps at the coast, hunting camps in the woods. Back yard gardens, back yard chickens: agriculture given way to oil field support. Last Borden’s Ice Cream store in the nation. Dance the two-step at Blue Moon Saloon to Feufollet and Lost Bayou Ramblers. Krewes and courirs of Mardi Gras, beads stranded in the limbs of oak trees all year long. Kayak Lake Chicot, Lake Martin, Lake Fausse Pointe. Segregated city, de facto segregated schools: poor and black northside, affluent and white along the river. Meet in the middle? Festivals Acadiens et Créoles, Festival International. In the city, two public access points to the Vermillion, its winding swath obscured by private estates. Eluding silence, I write amid fragments, from journals, photographs, memory, archives — time capsule of a disintegrating world. A place and an idea impossible to reconstruct, it falls apart in my hands, its multitudes. What are these fragments, this narrative? I build a box of loose pages, maps, stray keys, and seeds. Memento mori. What to keep, what to give away? What will not come with me, or might? Here and not here, what to make of this place called home?

An archive is an act of memory and affection, of loss: adrift upon a skim of oil, a scud of cloud, fragments on the floating Gulf.

[N.B. Other poems by Marthe Reed appear here and here on Poems and Poetics.]

Poems and poetics