Jess’s O! : An unknown masterwork (by Jack Foley)

Even is come; and from the dark park, hark.

— O!

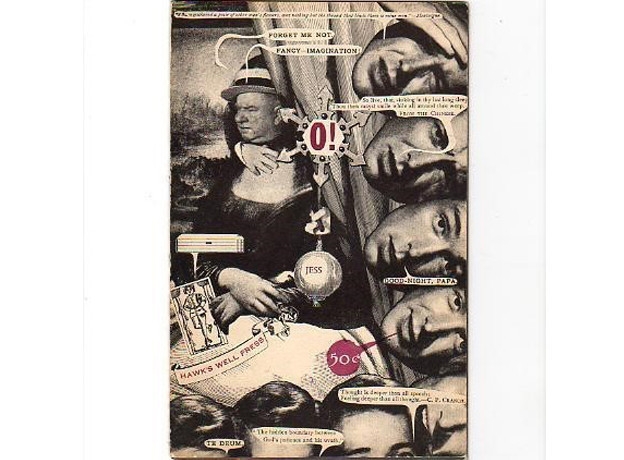

What do W. C. Fields, the Mona Lisa, an upside down Tarot card, and the capitalized phrase, “GOOD NIGHT, PAPA” have in common? Not much, except that they all grace the cover of an almost unknown masterwork by the San Francisco artist, Jess.

O!, a pamphlet of Jess’s poetry and collages — his preferred word is “paste-up” — was published by Jerome Rothenberg’s Hawk’s Well Press in 1960. It sold for $0.50. The book must have seemed fresh, even amazing at the time. Fifty-seven years later, out of print and impossible to find except in Rare Book Rooms, it is still fresh and amazing.

The upside-down Tarot card is “The Hanged Man,” but, upside down, the figure looks like a dancer. W. C. Fields is saying, “FANCY — IMAGINATION!” It’s a joke: fancy that, imagination! But it’s also a play on Coleridge’s categories of mentation, Fancy and Imagination. A sharp-pointed piece of metal seems to be penetrating W. C. Fields’s ear. Fields’s face is stuck onto the Mona Lisa’s, so we don’t see her at all: we see his head (with straw hat) above Mona Lisa’s bosom. The resulting figure is androgynous — part male, part female — but it is created in an extremely playful way: Jess does nothing at all to disguise the fact that he is deliberately manipulating these images. At the top of the page is a statement attributed to Montaigne — a kind of credo for the entire book: “I have gathered a posie of other men’s flowers, and nothing but the thread that binds them is mine own.”

Quotation, disruption, imaginative play, and a sentimental if ironic evocation of childhood are all elements of O!, as is a subtle, persistent homoerotic content. The book has a “Pre-Face” by Robert Duncan, who calls O! “art that is that very genuine phony fifty dollar bill — but it’s a three dollar bill.” (“Queer as a three dollar bill” was still current in 1960 America.)

Duncan goes on to comment that in this book, “which is in every detail derivative,” “something funny” — “amusing,” but also “odd,” “queer” — “is going on.” In O!’s “multiphasic” context — in which anything may be anything else — W. C. Fields, “stuck on” the Mona Lisa, may well be the phony fifty/three-dollar “Bill” (as the comedian was known to friends), a figure for the artist himself. Across the page from Duncan’s comment is a diagram of a lunar eclipse, in which the word “moon” becomes “moo” — the sound of the cow jumping over it — and “earth” drops its first and last letters to become “art.” “Jess,” writes Duncan, “has swallowed Dada” — cf. “PAPA” — “whole.”

In Secret Exhibition, a book dealing with West Coast Beat art, Rebecca Solnit has a chapter on Jess as a “painter among poets.” Jess cites “Max Ernst, Jean Cocteau, Antoni Gaudi, and San Francisco’s rococo Playland-at-the-Beach (particularly the funhouse) as important influences,” Solnit writes. “The impurity and the levity [of his work] were an outrage … in a way that is hard to imagine in the laissez-faire art world of the present … [I]f the work of Jess, [Wallace] Berman, [Bruce] Conner, and [Edward] Kienholz is considered as part of the canon of American art, it becomes clear that surrealism, with its insurrectionary wit and adoration of the absurd … became a potent way to address the incongruous realm of American experience.” One thinks as well of Chester Hines, whose novels often have surrealist elements: indeed, for Hines a “racist” society is an “absurd” — and so a “surreal” — society.

The underground world in which these artists functioned, Solnit goes on, “has remained a kind of public secret — some of Jack Kerouac’s novels take place on its periphery, and its literary aspect has been touched upon in books about the Beat Generation — but the importance of the artists in this time and place is still a well-kept secret.” “Barely acknowledged at the time [Beat] poetry was acclaimed,” Beat art “is some of the most lasting and influential to have been made during those years.”

O! contains many fragments of verse as part of its texture. Often they appear in something like comic strip balloons, so that figures in the paste-ups appear to be speaking them. But this book is particularly significant because it is one of the few presentations of Jess’s own poetry, which is little known. (When I mentioned Jess’s poetry to poet Thom Gunn, a close friend of Duncan’s and Jess’s, he said immediately, “Jess doesn’t write poetry.”) The influences here are primarily Lewis Carroll and James Joyce — particularly the Joyce of Finnegans Wake. Jess’s first poem was written in response to the Wake, of which he owns a signed edition. Here is a sample:

PTARRYDACTYL I

I’d need

a linnet on a spinet to be infinite

(Indeed

a spider as a glider’d not be wider).

But the butterfly

ought to utter why

new roses don’t suppose us worth the gnosis.

The poems are presented in white boxes, in which we can consider them separately from their surroundings — images, fragments of quotations, etc. Yet the surroundings constantly impinge upon the poems. “Ptarrydactyl I” is presented sideways on a page which includes, among other things, “Ptarrydactyl II,” bits and pieces of sheet music, diagrams probably lifted from the pages of Scientific American (Jess began his working life as a chemist), a Cupid perched on a child’s shoulder (the Cupid appears to be driving a nail into the child’s head, just as the child is driving a nail into a top hat), the word “VOLTAIR,” and the punning phrase “SCENE IN TEXAS.”

Images and phrases also extend across both sides of the book’s pages. We find unattached hands, animals (a zebra, a gnu, a tiny fox slinking away and saying, “O it is monstrous! monstrous!”), a man’s profile (the ear is on one page, the eye, nose and mouth on the other), smaller versions of the Cupid on the boy’s shoulder, and a trolley car with the word “VACUUM” on its side. The more you look, the more you see. The poems in the boxes thus seem to be emerging out of a teeming world which is at once orderly (we see reflections, parallels, verbal and visual puns) and vastly chaotic — a parallel universe which contains everything present in our own, but changed, distorted: reminiscent but wildly different.

Duncan rightly calls O! “a masterly hodgepodge.” Its prose and poetry, its fragments, its marvelous, resonant images create a picture of mind or self as an infinitely shapely chaos, charged at all points with what the artist will call later, quoting Shakespeare’s Troilus, “changeful potency.” In the book’s persistently free environs, boundaries are at once asserted and demolished; childhood merges into deep history; realism turns to magic — to say nothing of kitsch. Indeed, though Jess never considered himself to be part of the Beat movement, “Beat” is present here too, and it is present precisely as it is in Kerouac’s Mexico City Blues — as the ecstatic manifestation of the simultaneously infinite and finite character of the mind:

What are they? A child’s simple prattle,

A breath on the Infinite ear

*

Beats may be produced by singing

flames.

Ludwig Wittgenstein answered the famous opening sentence of his Tractatus, “The world is all that is the case,” with a sentence in Philosophical Investigations (I:95): “Thought can be of what is not the case.” Jess’s book is a boisterous ride through a mind blissfully open to its endlessly unraveling uncertainties, through what is precisely “not the case.” It is utterly of its time and utterly beyond it. I first came upon it almost by accident in the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley, where you can still find it. You can also find it, reproduced — one might say reconstructed — in Michael Duncan’s Jess: O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica (siglio: 2012). Jess’s “heart irregularly igneous” is present throughout:

So patter me with formulae

with syllables-a-mercy,

and tell me that the poem you see

is better late than early,

and draw me that the scene you hear

overestimates the nucleus;

the particles will pester Guenevere

in my heart irregularly igneous.

POST SCRIPT: NOTES ON THE RHYMING OF A COLLAGE ARTIST

My dear Degas, poems are not made with ideas but with words.

— Stéphane Mallarmé

PTARRYDACTYL I

I’d need

a linnet on a spinet to be infinite

(Indeed

a spider as a glider’d not be wider).

But the butterfly

ought to utter why

new roses don’t suppose us worth the gnosis.

— Jess

At the very center of Jess’s poetry is rhyme. In the recent resurgence of formal poetry, one often finds poets used to free verse attempting to force their “ideas” into the prison of rhyme: “Rhyme,” one of them remarked to the formalist X.J. Kennedy, “won’t let me say what I want to say.” “Yes!” Kennedy answered. In Jess’s work, as in Kennedy’s, rhyme is not an imprisoning element but a liberating one. Jess does not begin with “ideas”; he begins with words — rhyming words. “Meaning” is not something that exists previous to the rhymes; on the contrary, “meaning” is what rhyme can discover.

What then is rhyme? The sudden conjunction, through sound, of words that are in themselves entirely disparate.

What is collage? The sudden conjunction, through juxtaposition, of images that are in themselves quite disparate: “As beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table” (Lautréamont).

The Internet has this to say about Lautréamont’s famous sentence:

“This metaphor captures one of the most important principles of surrealist aesthetic: the enforced juxtaposition of two completely alien realities that challenges an observer’s preconditioned perception of reality. German surrealist Max Ernst would also refer to Lautréamont’s sewing machine and umbrella to define the structure of the surrealist painting as ‘a linking of two realities that by all appearances have nothing to link them, in a setting that by all appearances does not fit them.’”

“A linking of two realities that by all appearances have nothing to link them.” Isn’t that precisely what rhyme does?

And doesn’t chance — “le Hasard” in Mallarmé’s famous phrase — haunt both procedures?

Jess’s work is a discovery of rhyme as collage.

Poems and poetics