Ahmad Almallah

from ‘Bitter English’ (2019) and ‘The Border Wisdom’ (in progress)

BITTER ENGLISH

that I own no one language cuts me through

that I find this english tongue I use day after day

boring, in construction, even in poetry cuts me

in the middle of sentiment and sentence

I do not understand this sound, I stumble,

as I say to myself I will ignore these english words

emptied today, I walk down the street catching

my hand in the air, greeting faces I know I don’t know

as I walk these streets only owning past echoes

cutting through this language, this english tongue

I want to catch with my teeth, cuts me through

that I have to stack all my old and new passports

on my writing, cuts me through, I go over

my exits and entries for this citizenship, my first

step, I doubt, to owning something of this sound

I owe everything to one place that owns me, not

here, where what I owe I do not own, time and many

years spared because this english tongue cuts me

through, because this english tongue owes me

a language

from THE BORDER WISDOM

mis/translation:ONEترحّلتُ وتساءلت عن ضياع اللغة هذا. أين أجدها وكلّ ما أعرفه منها ذلك الصوت الواحد. هل[ONE language, silence] / When my mother died, June, the second, twenty and twenty one, when[left was right and kept pushing against every attempt to put down any words — how could the world speak anything but her language and sounds]:

كتبتُ بلغة المنفى لأجد شيئاً مِن الأمّ في ركام المعاني؟ هل يجد المرء أمّه في منفى اللغة؟ في

Her body remained without her in the form, I could no longer write in any

الشعر؟ في صمت الكلمات؟ لم يبق لي إلّا السؤال وكل الأجوبة تبقى معلّقة مؤجّلة؟ تلك هي

Adopted sound, poetry was left behind

without its source; I only wanted to

لغتي، تلك هي أمّي، وهذه كلّ قصائدها: صمتٌ يحثّ على التساؤل وأسئلة لا تقبل الإجابات...

hear her voice, but there was that silence, the language she mastered, and the mother

tongue happened to be Arabic — everything she said, and didn’t say like the sword, one

and cutting through everything real, in a reality devoid of speech her sounds I could not write in any form

that strayed away from those original sounds I inherited from that one mother that rarely spoke

but when she did, it was only in Arabic, and all she could remember of her English lessons, is the phrase

that made fun of her inability to be with anything but Arabic she said, that all she remembers

of English, a half definition, that “an inventor is a man or woman …” I can see her clearly, strangely

when she was near the light, by the frame of the door to her bedroom saying those only English words she spoke,

to laugh with me, to laugh at herself, and to always make sure I remember that

school lessons

are not to be taken

seriously.

[I wish you could do things without the mind

she always said: a craft of some sort to save you from those lessons your father gives] —

تتراكم ذرّات الصمت هذه هنا وهناك. أجمُعها ذرّةً ذرّةً. أسترجع بها هزائمي مع العربية، لغتي التي لا أقوى عليها الآن. لأنّي لو قويتُ عليها لرددتُها ــ كما قالها الأوائل ــ قالباً قالباً. وأنا الذي لا أجيد ترديد الأقوال، بل أردّد الأصوات التي حضنتْني، أردّد أصواتهم علّني ألتقط بعضاً من أصداء صمتهم، ثم أودّعهم عندما يحين وقت الكتابة.My defeats with the Arabic language keep up keep me up yup the American English of NOPE.

THE NAME ELEGY, NAWAL

*

Every moment is an image. Every sunrise is a flashback

to the other side

where the dead never reach out to the living who

obsess about connecting

dots and making symbols:

my daughter gives me knives to celebrate

the fancy fact that once upon a time, like a sad

story you existed and you loved to cut and puncture

then carve and preserve:

the blocks of time between being born and being rendered

an aching body ready to receive the final blow make up

some life to celebrate and then cut cut

cut again the only slice of air is that body

the language that you mastered to the tiniest twitch: what

statement were you trying

to make god knows only grief

will make the ones left behind decipher and

then the image might come alive because it is real

and contains gaps like the real yes the real that is

the hardest to

imagine.

*

From memory, a mother, I create your absence

— Nawal, the name attached to the body, is no —

No longer a reality, no longer a reference to some-

One there: is it really possible, your disappearance?

Just like that I hear

You are gone, after you were

Here, with us: then I pack and spend the hours flying,

Only to see your grave, the empty bed, the needles

And the tubes left alone at last. To gain

Some understanding of that thing we call death I fly

Back home to where I no longer know:

Cramming the body into tight spaces and vehicles,

Into the corners of structures here and there

That are now as small as the hole in the ground

They stuck you in.

Was it too much to ask

That I be by your side

To lay you down in the ground, to wash you

Of the filth of living before you be done with

Light, and into the darkness we call

Grave you were no

More.

*

Sometime in May, another war in Gaza is on its way

In the room we save for the living, I watched the buildings

Leveled to the ground dust dust dust rising in a cloud

And more dirt to contend with. I was in Beirut calculating

My next move: should I go back and wait for your eventual

Disappearance, or should I go and try to bring

Everyone back to you? I thought you’ll wait for me, for us,

Time and again — I was wrong:

I never thought a war would erupt, and like a sad smile

It did.

*

Everyone sleeps in these lands, but here it happened, to

Interrupt and trip me again, another war. Everyone I know

Wanted me out.

Get out of the middle, you crazy jumble

of trouble. Don’t come back! Look at the signs!

The war, another fact on the heap:

You don’t have a father or a home. You

Stayed at

A hotel, like a bastard, and only felt at home in the ICU, be-

Side your dying figure of home: your mother: what was she,

a ghost? A

Shadow?

What was she? What were

You then

Mother?

*

I came and carried her to her last hours, it seems. It was

Ramadan and everyone wanted to break their fast but she

wanted to die. I had to come at that hour, and

Carry her, carry her with both hands, up the steep stairs,

with the medical crew, to the

Hospital you were born in, to that awful place that was

Death itself, where the sick lay in hallways, waiting, for

The living to let them go.

Mother, you named me there, you said

To father then, who named and labeled everyone else

You brought to life:

I want to name this one.

*

I made a myth out of that Ramadan trip,

I was your savior:

I was asked to hold your blouse above your breasts

I watched the doctors stick needles near your heart

I saw them clamping sharp metal things into your sagging skin

I held on tight: your body shaking, asking for air —

I felt the touch of death then and there

I guess that other world is possible

I guess you were almost gone

I gathered so, from the hubbub of medical talk:

Why did I have to come at that

Hour, running from the hotel

Upon my arrival, when I received

A call from my sister: Hurry hurry!

After three years, I ran, now

A child nearing forty, I ran

To see my mother, thinking

For the last time.

*

Should I, mother tell you this story

how aware were you of what was happening to you, around you? When after “I saved you” I had to leave again:

I broke down, shouting: how did we let you get to this state

I summoned not poems everyone that was there father my two brothers

And shouted at them: how did we let her get to this state?

Were you witnessing any of this?

I looked at you for the last time you returned my gaze

but you were calm no longer insane simply subdued

drenched to the lees ready for death you didn’t make a sound

You looked at me a last glimpse

From that corner of your wooden

Pain.

*

Yamma, I tried to warm up to father give him a chance, but I was caught

every time

How could I accept this new arrangement you dying in the lower level of the house while

He and his wife served me Kunafa and coffee after breaking fast I made it clear I was not Putting up a show this time

I didn’t fast I know you would have rather I did

I smoked in front of him

I was there to make things messy uneasy for the old fucks the newly wed

Something was eating at me every time I found myself

In what used to be your house with another woman roaming around locking me out When she needed to

Is it really no longer yours her house?

But I wasn’t there to make that women’s life hell I felt sorry for her

How can she bear all this? Us talking non-stop about us about you.

*

What was I there for? I told him on that last night

What you privately said to me and to others

That because he was what he was he pushed us

Out of house and country

And you had to bear his burden

Left alone without your children

You couldn’t make meaning of it all

You prayed to Allah, just like he did

But I think you were beyond it all at a certain point

You didn’t care about a thing —

Alone

Abandoned

The world began

Eating at your brain.

*

In a dream, I was in Palestine, I was

Coming back as I always do

In my dreams

You were alive and well it seems:

My father lied to me again

About your death

He couldn’t face the fact of your

Non-Absence, and the only

Remedy to the

Rift between us: was your passing —

He made up death, another

Excuse.

*

1967: When you were a young girl in Hebron

Palestine —

Against all odds you went to Amman, out of

Your home, as a woman on her own, to study

And meet your man, this father of mine. You

Made him a promise, to wait for him till he

asks for your hand.

It took him a few years, three to be

Exact. Were you that in love?

Three years without a word.

Maybe that was your first mistake —

Keeping your promises. Maybe that’s why

I should never keep

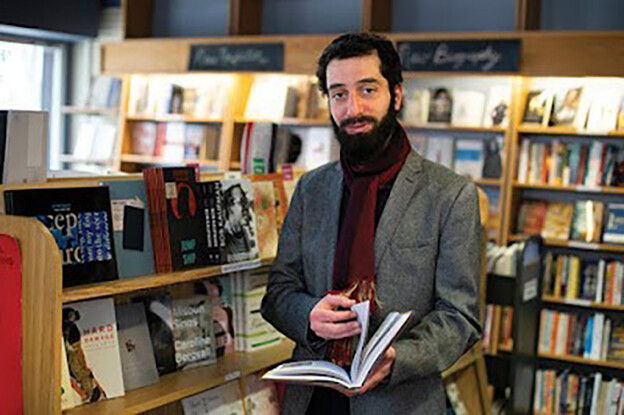

BIO NOTE (after Al Filreis). Ahmad Almallah was born and raised in Bethlehem, in the central West Bank, about six miles south of Jerusalem. For twenty years he has lived in the US, where he has earned a PhD in classical Arabic poetry (at Indiana University), was appointed to a tenurable assistant professorship at Middlebury College, and has worked on a book on Arabic love poetry and the ghazal. He left Middlebury (left the tenure line!) and moved with his family to Philadelphia, where he devotes more or less all his time to writing poetry in English.

EDITOR’S NOTE. Almallah’s first book of poems, Bitter English, was published in the University of Chicago Press’s Phoenix Poets series in 2019, while his follow-up work, The Border Wisdom, is still to be published. It is in the latter, however, that he takes the notable step of writing in a mix of Arabic and English scripts, as above: a contemporary instance of bilingual poetics that has surfaced intermittently among the finest of our experimental writers. For this and for his exemplary writings in standalone English, I would extend to him the well-known welcome that Emerson directed to Whitman nearly two centuries ago. (J.R.)

“I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

Poems and poetics