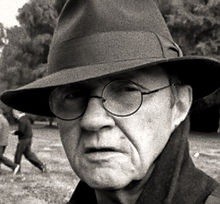

Arkadii Dragomoshchenko: 'Paper Dreams,' for Jerome Rothenberg

Translation from Russian by Genya Turovskaya

Black paper dreams of its own

inaudible rustle;

its own reflection in white.

Heat drowsily gazes at heat

through the panes of passion.

Metamorphoses of water.

Carrying reflections

down to the bone’s marrow,

the mirrors of droplets dry up.

Black paper dreams

of black: its dream constrained

by the nature of non-color.

Through the membrane--

the single-mindedness of repetition,

through the body--the needle flies,

bereft of thread, of decay.

Shadow falls upon brick walls.

The gematria of melting,

of exclusions.

The letter dreams of the same

paper's rustling,

in which hearing distinguishes

the contours of a poet,

who dreams of Hasidim

burning out as a page of song

on the stones of the ocean,

reducing vowels to gesture.

The dream dreams a dream of consonants,

the page--

where black assumes

the limits of incision--

dreams of the borders of the letter, mica, light.

I love to touch with my lips

the tattoo at the stem of your shoulder,

(the calendrical whirl of the Aztecs),

so that word may open to word.

Again there isn’t enough money,

images of sand and wind,

to buy wine.

Each dream, exposing

the honeycombs of visions,

engages thread into motion:

fingers slipping downward

(Guétat-Liviani, Frédérique)

spin a cobweb

--the tenderness of violence--

the ethereal fabric of recognition

in intensity and indication.

However quiet

your voice may be.

However much it fills coincidences

with hesitant executions.

The fingers dream of the keyholes

of song, exuded by stones,

that see in their dreams

the azure salts of the sun,

the blade’s whistle, water’s branch,

that see in their dreams

skin, celestial bodies, teeth,

the tattoo of indistinct speech

on the standards of breathing--

such are

the touch of tongue to tongue,

of saliva to tongue;

such are the outspread arms and legs

of a man and a woman,--

the golden mean on the book’s cover,--

who dream of pages

over which the night saunters,

and the night is dreamt by speech,

like the throat of heavy light

and the sign’s endless ribbon

that engirds those who are

slowly bringing their hands together

as if the fingers grope for something else in the bend.

A desert,

imprisoned in touch.

Wine sees in its dreams

all the forementioned things,

that cross into diminution

along the steps of un-thinging,

(an unhurried narration),

and I, examining the wine

that lives in glassy limits,

like the threads

of fusion and touch,

falling from the fingers

toward the puppets of flight

in the gardens of noontime tortures.

The sign--is the quietest razor of darkness.

Wine has no “right”

no “left.” Death

has no name--it is only a list,

the spilling over of the two-way mirror,

where the equal sign is rubbed away

to the differentiation

between man and woman.

[NOTE. Arkadii Dragomoshchenko came to us first as a samizdat/underground poet, his lines & gestures signaling an opening to new discoveries & freedoms in what had been the closed world of the Soviet superstate. That freedom as a poet resided squarely in the heart of his poetry – its language & form serving as the conduits for thoughts & realities previously obscured. With that much behind him his work emerged on the American poetry scene through the good works of Lyn Hejinian & a number of other poets closely or loosely connected with the Language Poetry movement. That his poetry is remarkable on its own terms should be evident – the summary by Marjorie Perloff clear enough: “For Dragomoshchenko, language is not the always already used and appropriated, the pre-formed and prefixed that American poets feel they must wrestle with. On the contrary, Dragomoshchenko insists that ‘language cannot be appropriated because it is perpetually incomplete’ ... and, in an aphorism reminiscent of Rimbaud's ‘Je est un autre,’ ‘poetry is always somewhere else.’” (J.R.)]

Poems and poetics