Milton Resnick, poet — In memory — An essay & a poem

[The following coincides with a major exhibition (May 10 to August 1) of Milton Resnick’s work over a six-decade career, sponsored by Mana Contemporary of Jersey City and the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation.]

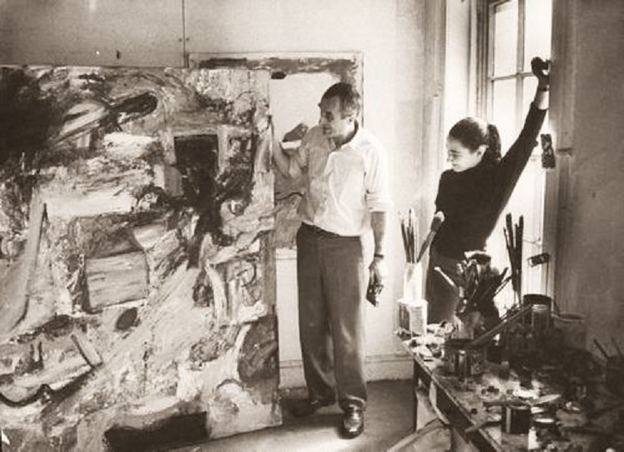

Milton Resnick walked in on me while I was tending the Blue Yak Bookstore on East 10th Street, showed me his poetry, in three small, neatly printed pamphlets, & later taught me, as I came to know him, what it meant to be devoted to art as the center & pivot of a life. The year must have been 1961, since the Blue Yak didn’t last for more than that year, & probably in the spring, before Diane & I went off to Europe in the summer. (The store had vanished by the time we got back – or if it hadn’t completely vanished, was on the way to doing so.)

Milton’s declaration, right from the start, was that he was a painter who had given up painting in favor of poetry & that he thought that I & my fellow poets should now give up poetry in favor of painting. I took him at his word – or pretended to – & for a part of the next year I busied myself with photomontage or collage & even got into painting for a spell, when Diane & I hid away for a week on a small island (Picton) in the St. Lawrence River. My commitment to painting wasn’t very deep of course, but I learned something from Milton & from the actual feel of doing it, the act (however brief for me) of being in it. I wrote about it too, as follows, though I think it got into my poetry in other ways as well:

I sweat too much, I have

a long way left

& I would like to know death

not as this fear

but as my hand touched form

when painting

opening, the shadow of a color

on my arm

[from “Three Interiors” in Between, 1963]

But what was much more important for me was Milton’s work & presence – a ferocious devotion to painting & to whatever else it was that drove his own work. He was uncompromising & quickly dismissive of what he didn’t love – a temperament in that sense very different from my own – but his loves were also powerful & contagious. It was his enthusiasm, I know, that first turned me to the paintings of Arshile Gorky & led to a book-length gathering of mine I called The Gorky Poems. I didn’t dedicate the book to Milton, as possibly I should have, but I have a sense that I borrowed from him a certain ferocity – something of his rant, I thought, more than of mine or Gorky’s, or something in the mix along with ours:

What men!

What stone in their voices!

What glass in their blood!

What iron! What flesh!

What bright eyes!

This stone, this iron

in a dream

Still worse when no one dreams it.

[from “The Pirate (II),” in The Gorky Poems]

I was also deeply moved by Milton’s poetry, to which my first response, as often the case in those days, was to publish a group of his poems in the magazine I was then publishing & editing, Poems from the Floating World. I had an idea, even then, of the ways in which certain artists had crossed or blurred the line between poetry & painting (or between poetry & art, to put it that way) – Arp, Picabia, Kandinsky, Ernst, among the ones whom I was then pursuing, & Schwitters & Picasso the ones I would pursue much later. In Milton’s four small books – Up & Down, followed by Journal of Voyages 1, 2, & 3, all published consecutively in 1961 – I found an equivalent shift from one genre to another. It was not a question of mixing genres, which began to interest me in work by other poets & artists who were then emerging, but of carrying the intensity he had lavished on painting into a new medium – that of words. That he did it instantly & with equivalent grace & fury astonished me, as did his natural & credible assumption of the poet’s [bardic] voice:

I release my poems upon cities

upon cities

a human soul circles

towers of smoke

lance the sky

& again, from a place of anxiety shared by many a poet/artist “in advance of techne”:

yellow fingers scratch showers of sweat

I make a noise in my throat

black be blacker be feared

fear teaches poetry

whose double pin hooks deep into all of us

Some of that fear, I came to think, was a Jewish thing – at least that image came up very strongly when he & Pat Passlof moved from the East Village into the abandoned synagogue they bought, circa 1963, on Forsythe Street. I had begun to work, however tentatively, toward Poland/1931, which would be my attempt to resuscitate Jewish “identity” & simultaneously to put it into question, so the synagogue (one of many in what had been the heavily Jewish Lower East Side) was a point of fascination for me. It was for him also, something that he described to me as a “return” – to a place where he could go & “be a kike again.” That was exactly how he put it, though by the time he got there, Forsythe Street had turned heavily hispanic & was – their block at least – a dangerous part of a notoriously dangerous neighborhood. In the midst of that Milton & Pat turned their synagogue into a green paradise, filled with plants & birds, a workplace & oasis in a hostile world.

Our last dinner at their place – before Milton got his own synagogue on Eldridge Street & the neighborhood turned decidedly Chinese – was one that still stands out in recollection. It was late into the evening & we were sitting in the sunken part of the house, a large high room below street level but with tall windows facing onto Forsythe Street. There had been some talk about drug pushers & other local dangers, all of which Milton put down in favor of his sense of a “return.” It was in the middle of that talk or soon thereafter – with dinner, I think, already over – that we heard several loud bangs from the street outside & looked up – startled – to see a body, illuminated by a street light, dropping to the ground. We continued to watch in silence as other murky figures loomed up & the rotating colored lights of a squad car came on the scene with siren blasting.

I hardly remember what else we saw – an ambulance at some point & the movements & voices of shadowy spectators after the fact. Finally the street emptied out & there were no sounds coming back at us. No one seemed ready to say anything, the rest of us looking toward Milton to see how he would respond. There was a long pause – very long – & Milton then said – to no one in particular I thought: “I have never felt so safe in my whole life.”

I treasure that moment in memory, as I treasure his art & the devotion he gave to it even when he turned from it in anger. That anger I think never left him but I would also like to believe that he maintained alongside it the determination to be the master of his life & death against all odds. He will be remembered for the beauty & reality that his art brought into the world, & in my mind at least he will remain a real poet, a fellow poet, as he was when I met him back in some mutually vanished past.

*

[What follows is an example of Resnick’s work as a poet, first published posthumously along with other poems in Poems and Poetics.]

An Accident

An accident on the mountain

showing the superiority of chance

I fell and thought I saw horses in the sky

the horses shiver

they don’t understand if you don’t whip

what’s more false than the horse of dream

the race, the grass, the sun

I should doubt for a painter nature is a paradox

but you don’t need me to mix colors

what one likes does not trot out of painting

dreams still function

they could be expressing the mystic

the indistinct line of nature wanted for great art

I know this anxiety

allowable in the forced loneliness of the studio

and for the god-forsaken Jew hiding as someone else

but for the god-like that explode in song and dance

the drum won’t do

and idealistic protest will not win the field

for the years deliver us of pity

yesterday for instance I stopped reading about

the earthquake in Mexico

I thought the news was getting beyond nightmare

beyond everchanging shadows lying in wait for dawn

the rosy-fingered beyond the likely

as for me I hardly recognize the day

It’s so early something in the air threatens

insects the horrors eat

they need the blood you need

they take from us that we have none

cast in hell as usual

if all that talk of sin comes to pass

the parades I shall see

new light on what I know and feel

all in a single drop is nothing

in the presence of the mountain

a mad thought —

I don’t look a thing grinning in pain

Poems and poetics